Antonio Vieira

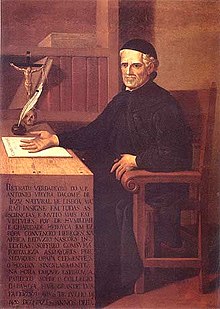

António Vieira [ ɐnˈtɔni̯u ˈvi̯ɐi̯rɐ ] (born February 6, 1608 in Lisbon , † July 18, 1697 in Salvador da Bahia , Brazil ) was a Portuguese Catholic theologian, Jesuit and missionary in South America. He is considered the apostle of the Indians of Brazil and distinguished himself as a popular preacher and critic of colonial ills. He also worked as a diplomat for Portugal.

Life

Vieira came to Brazil with his family as early as 1614 (at the age of 6). He was trained at the Jesuit college in Salvador da Bahia, became a novice in 1625 and was soon teaching rhetoric and dogmatics at the college in Olinda . In 1635 he became a priest and began his missionary work in northeastern Brazil with the Amazonian tribes . In 1641, after a revolution in Portugal with John IV brought the House of Braganza to power in 1640 , he returned to Europe to accompany the viceroy's son on an inaugural visit. The king was taken with the spirit of Vieiras and this entered into advisory and from 1647 diplomatic services for John IV with stays in England , Holland , France and Italy . In 1650 he made a trip to Rome to prepare the wedding between Anna of Austria and the designated heir to the throne Theodosius, but this failed. At that time he wrote very eagerly, for example, four pamphlets in which he proposed the creation of trading companies, a reform of the Inquisition , for overcoming the distinction between Cristãos-velhos (ancient Christians) and Cristãos-novos (Jews who had converted for several generations or Moors) and the admission of Jewish and other foreign traders in Portugal. He made a significant contribution to the establishment of the General Society of Brazil Trade. In addition, he denounced the style of preaching of his time, which was too aloof, which should instead dismiss the listener " not satisfied with the preacher, rather dissatisfied with himself ".

However, his reform ideas also made him enemies, so that only an intervention by the king prevented his expulsion from the Jesuit order. He therefore returned to Brazil in 1652. He arrived in Maranhão in 1653 and traveled from Pará to the Rio Tocantins , where he proselytized among the native Indians. However, since the colonial administration often hindered him, he saw the need not to allow the state to rule over the natives, also in order to prevent their exploitation, and therefore traveled to Portugal again in 1654 to convince the king to take the land under the To provide custody of the Jesuit order. In 1655 he actually succeeded in gaining control of an area comprising a coastline of about 400 Legoas (about 2200 km) and an estimated 200,000 people by decree from the king.

In 1661, the anger of the European colonists, who feared for their prosperity if the Indians were given more and more rights, discharged, and Vieira was sent back to Portugal with 31 other Jesuit missionaries. His patron Johann had died in the meantime and some figures at court feared for their influence, so that Vieira was sent into exile to Porto and then Coimbra , where he did not stop his uncomfortable sermons and was finally charged with heresy before the Inquisition . He was imprisoned from October 1665 to December 1667 and was subsequently banned from teaching, writing and preaching.

After King Peter II took office, Vieira was given the chance to rehabilitate himself in Rome with Pope Clement X , where he was able to gain great respect again. So he was given the opportunity to speak before the College of Cardinals and became confessor of Christina I. He also wrote a report on the Inquisition in Portugal with the result that this was done by Clement XI. was suspended between 1676 and 1681. Finally, after the Pope granted him exemption from the Inquisition in a bull , he returned to Portugal and embarked for Brazil in January 1681.

He settled in Salvador da Bahia and in 1687 took over the management of the province of Bahia , which he held until his death in 1697.

He is particularly known for his writings in which Vieira condemns slavery , among other things . The Sermões comprise a total of 15 volumes that appeared between 1679 and 1748. A complete edition was never published, so parts of his writings are still unpublished today. Some of them are considered to be masterpieces of Baroque prose and one of the highlights of Portuguese literature. In his “History of the Future” he demands that Jews should be allowed to settle everywhere, since their conversion will take place anyway in view of the impending apocalypse . During the time he lived with the Indians, he learned several of their languages and coined many foreign words in Portuguese and other European languages, which he adopted from the Indians and incorporated into his writings. His political ideals with the commitment for the rights of Jews ( Marranos ) and Indios and the rejection of their economic exploitation and the rejection of materialism in general seem very modern for his time.

bibliography

- José Pedro Paiva: Padre António Vieira, 1608–1697, Bibliografia. Biblioteca Nacional, Lisboa 1999, ISBN 972-565-268-1 .

Fonts (selection)

- António Vieiras' Sermon to the Portuguese Estates General of 1642 . Edited by Rolf Nagel. Aschendorff, Münster 1972.

- António Vieira's plague sermon . Edited by Heinz Willi Wittschier. Aschendorff, Münster 1973.

-

História do futuro . (1649) Edited by Joseph Jacobus van den Besselaar . Aschendorff, Münster 1976.

- Vol. 1: Bibliografía, introdução e texto

- Vol. 2: Comentário

- António Vieira's sermon on “The Visitation of the Virgin Mary” . Edited by Radegundis Leopold. Aschendorff, Münster 1977.

- António Vieiras sermon on Rochus from the year of the Restoration War, 1642 . Edited by Rüdiger Hoffmann. Aschendorff, Münster 1981.

- Antonio Vieiras Sermão do esposo da Mãe de Deus S. José . Published by Maria de Fátima Viegas Brauer-Figueiredo. Aschendorff, Münster 1983.

literature

in German language

- Jürgen Burgarth: The negation in the work of Padre António Vieira . Aschendorff, Münster 1977.

- Carl-Jürgen Kaltenborn: Antonio Viera (1608-1697) - Biographical sketch of a liberation theological precursor. In: Think alternatives. Critical emancipatory social theories as a reflex on the social question in bourgeois society. Published by the Central Institute for Philosophy. Central Institute for Philosophy, Berlin 1991, pp. 23-25. (Colloquium on “Alternative Thinking”, October 4th and 5th, 1991, Berlin).

- Maria Luisa Cusati: Father Antônio Vieira and Canudos : Messianism or Messianisms? In: The Socioreligious Movement of Canudos (1893-1897) , Vol. 1: History, Society and Religion . Verlag für Interkulturelle Kommunikation (IKO), Frankfurt am Main 1997 (= subject volume by ABP (Africa, Asia, Brazil, Portugal). Journal on the Portuguese-speaking World ), ISSN 0947-1723 , year 1997, issue 2, pp. 44–51 .

- Willis Guerra Filho: The theological-political problem of the enslavement of colored people in Antonio Vieira's thought . In: Matthias Kaufmann, Robert Schnepf (Ed.): Political Metaphysics. The emergence of modern legal concepts in Spanish Scholasticism . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 3-631-53634-8 , pp. 419-438.

in Portuguese

- Luis Gómez Palacin: Vieira . Ediçôes Loyola, Sâo Paulo 1998, ISBN 85-15-01688-5 .

- Joâo Geraldo Machado Bellocchio: “Parate Viam Domini”. Doutrina teológica dos Sermôes do Ano Litúrgico do Pe. Antônio Vieira, SJ (1608-1697) . Pontifica Universitas Gregoriana, Rome 2001.

- Arnaldo Niskier: Padre Antônio Vieira e os judeus . Imago Editora, Rio de Janeiro 2004, ISBN 85-312-0937-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about António Vieira in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about António Vieira in the German Digital Library

- Literature by and about António Vieira in the catalog of the Ibero-American Institute of Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin

- Works by Antonio Vieira in the catalog of the library of the Universidade de São Paulo

- Archival material on António Vieira in the archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University , shelf marks: FC 1165/1, FC 1165/2.

Individual evidence

- ^ António Vieira in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Josep Ignasi Saranyana u. a. (Ed.): Teología en América Latina . Vol. 1: Desde los orígenes a la Guerra de Secesión (1493-1715) . Vervuert, Frankfurt am Main and Madrid 1999, ISBN 3-89354-113-6 . Therein Chapter XII: La teología homilética del XVII , Part 5: Antonio Vieira, predicador del Brasil .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vieira, António |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Portuguese theologian, Jesuit and missionary |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 6, 1608 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lisbon , Portugal |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 18, 1697 |

| Place of death | Salvador da Bahia , Brazil |