Oppelschacht

| Oppelschacht | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information about the mine | |||

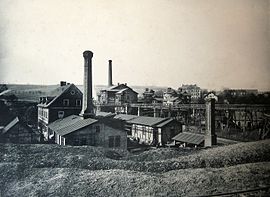

| Oppelschacht (around 1890) | |||

| Mining technology | Longwall mining | ||

| Information about the mining company | |||

| Operating company | Zauckerode Royal Coal Works | ||

| Start of operation | 1833 | ||

| End of operation | 1927 | ||

| Funded raw materials | |||

| Degradation of | Hard coal | ||

| Mightiness | 4.00 m | ||

| Greatest depth | 222 m | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 51 ° 0 '57.5 " N , 13 ° 38' 22.8" E | ||

|

|||

| Location | Zauckerode | ||

| local community | Freital | ||

| District ( NUTS3 ) | Saxon Switzerland-Eastern Ore Mountains. | ||

| country | Free State of Saxony | ||

| Country | Germany | ||

The Oppel shaft (1948: Arthur Teuchert-bay ) was a coal mine of the Royal coal plant Zauckerode . The shaft was in the western part of the coal deposit of the Döhlen basin on Zauckeroder Flur.

The shaft bore the name of Bergrat Carl Wilhelm von Oppel .

history

Oppelschacht

The Zauckerode Royal Coal Works began in 1833 at 193.95 m above sea level with the deepening of a main, art and production shaft, which was initially named Friedrichschacht . It was only after the death of Carl Wilhelm von Oppel in November 1833 that he received his name. The shaft disk measured about 5.15 x 1.42 meters. According to the state of the art at the time, the Freiberg machine director Christian Friedrich Brendel regarded it as sufficient for recording the art movements and the driving and conveying range .

After a depth of 16.10 meters, the work was stopped when the pump workers could no longer cope with the penetrating water. It was only after a hole was drilled in February 1836 on a cross passage that had been made from 1832 by the Zauckeroder Kunstschacht in the bottom of the Tiefen Elbstolln that the sinking work could be continued. The amount of water added was 5 m 3 / h. After just three weeks, however, the work had to be interrupted again. The stagnant water had so washed behind the expansion that a collapse of the shaft could only be prevented with great difficulty. The borehole broke through the masses of water and clogged. It was then pushed through again and cased to a depth of 56.70 meters. When the shaft reached a depth of 37.10 meters, the borehole under the casing blocked again. It was decided to drill a new hole, which on July 15, 1836 then reached the cross passage to the Tiefen Elbstolln. Other major problems arose when the excavation of the first borehole began at a depth of 66.60 meters. The 2.00 × 4.00 m large funnel partially extended beyond the shaft joints. When a main support punch with a diameter of 50 cm broke and the shaft timbering was postponed, they seriously considered abandoning the shaft. From February 4, 1837, the water could flow off via the now completed Tiefen Elbstolln. It was not until April 1839 that the depth of 66.60 meters was reached again after the shaft had been rebuilt and worked over. In June 1839, at a depth of 84.43 meters, the Elbe tunnel bottom was reached without any further problems. At a depth of 10.50 meters, a brick rose from the Wiederitz came into the shaft. After reaching the bottom of the Elbe and expanding the shaft, the depth was continued with a cross-section of 4.53 m × 2.26 m. The 4.0 meter thick first seam was cut from about 102 meters and the first main section was cut at a depth of 107.79 meters. The shaft was then torn down to its full size from bottom to top. In August 1840 the work was finished.

In the meantime, the boiler house and machine house had been built and a steam engine had been built for the extraction and water retention. The steam engine with an output of 18 hp was delivered in 1828 by Christian Friedrich Brendel in Freiberg for the 6th light hole in the Tiefen Elbstolln. When it was no longer needed there, it was moved to the Oppelschacht in 1840. The carrier was a bobbin with hemp ropes. Then one began with the further depth of the shaft. At 120.00 meters, the second seam with a thickness of 0.60 meters and at 127.80 meters the third seam with a thickness of 1.20 meters were intersected. At 131.57 meters, the second main line was struck and after a sump had been removed, sinking was stopped on December 31, 1841. On March 31, 1845, the water backed up in the Tiefen Elbstolln due to an Elbe flood and fell into the structures below the tunnel. This drowned up to 20.70 meters over the second main line.

In 1848, one end of the shaft was enlarged by 1.13 meters to make room for a wooden hanging strand. In 1851 the shaft was up to III. Main stretch further sunk at 155.95 meters.

In 1856 the shaft was connected to the Niederhermsdorf coal branch at its own expense , which made it much easier to transport the coal extracted. On November 25, 1856, the first coal was loaded for rail transport.

In 1867 the shaft was deepened to the fourth section at 186.62 meters. A comprehensive modernization of the technical systems took place in 1872. To this end, a cast iron and a new shaft building were built in place of the wooden conveyor chair . The obsolete carrier was also replaced by a twin steam carrier. Two-day conveyor racks have now been used for the promotion . They were equipped with a White & Grant safety gear. You could order two Hunte is recoverable. In June 1873, the team rode the rope on a trial basis . However, it was limited to the early morning and noon shifts. General team ropes were only introduced after 1881. In 1873 horses were used to promote the IV main route .

In 1873/74 the shaft was sunk to the V section at 218.25 meters. With the expansion of the sump, the shaft reached its final depth of 222.00 meters. Here too, the coal was transported by horses, with a train consisting of 10 hunts.

In the further construction of the mine field, several faults running south of the shaft were crossed with the III., IV. And V main line. The first fault was encountered at a distance of 240 meters from the shaft with a jump height of 8 meters. The second fault, the Beckerschacht fault, consisted of 4 individual jumps with a total height of 25 meters. They were broken through at a distance of 375 meters. The Carolaschacht fault found at a distance of 945 meters from the shaft with a jump height of 32 meters was only approached with the V main line.

Coal production on the V main line had risen to 800 hunts per day (16 hours). The horse promotion reached the limit of its efficiency. Therefore, the decision was made to use electric locomotive funding. The 720 meter long cross passage leading to the seam was expanded to double tracks. The mine locomotive supplied by Siemens & Halske took its first test drive on August 25, 1882. The locomotive, baptized under the name Dorothea (Greek, “gift of God”), was the world's first electric locomotive in continuous operation. It had a track width of 566 mm, a height of 1700 mm, a width of 800 mm, a length of 2430 mm and a weight of 1550 kg. She transported 15 full hunt at a speed of 7 km / h. The dogs were not pulled, but pushed. This saves the time of coupling and uncoupling. This was possible because the cross passage did not have a gradient. It replaced horse transport on the cross passage. The transport costs per hunt fell from 3.70 pfennigs for horse transport to just 1.69 pfennigs for locomotive transport.

An extensive mine fire that occurred in the southern district of the shaft in the Altes Mann in 1883 could only be contained and suffocated after several months by building fire dams.

In January 1889, the first electric chain conveyor was put into operation to develop supplies lying in a hollow . With a length of 400 meters, a height difference of 8.40 meters was overcome. The system was delivered by Schuckert & Co. in Nuremberg.

With the experience gained from using the first locomotive, Siemens & Halske built a second locomotive for the Oppelschacht. This locomotive was used in 1891. The first locomotive was kept in reserve. In addition to structural improvements, the new locomotive also achieved a 15 percent increase in performance. The transport costs per hunt were now 4.00 pfennigs for horses and 1.88 pfennigs for locomotives. The basis here is also 800 hunts a day (16 hours). After the shaft was closed, the Dorothea was returned to the manufacturer.

In 1892, the company Adolf Bleichert & Co. from Schkeuditz built a 720 meter long cable car. This transported overburden and piles of washing to a new dump to the southeast of the shaft.

In 1895 an electrically driven chain conveyor between the V. (−26 m above sea level) and the VI. (−46 m above sea level) main line installed. The system was developed by the Maschinenbauanstalt Humboldt AG

Reconstruction of the shaft began in 1896. It received a masonry shaft head down to a depth of 31 meters. Furthermore, a new brick shaft building and a modern headframe with a wrought iron pulley chair were built. The work was finished in 1897. The Oppelschacht was also affected by the Weißeritz flood on 30./31. Affected July 1897. For security reasons, the workforce left at 6 p.m. on July 30th. After the water ingress into the Ernst route , the pit horses were also brought above ground on July 31. The flood caused great damage in the southeast area. The III. The main route was only tackled up to the 40th lower mountain route. The further course up to the 50th lower mountain route, to which the Döhlener Kunstschacht is connected, was abandoned.

After traces of firedamp were repeatedly found in the north-west district in 1898 , the greater part of the Oppelschacht district was declared a firedamp pit. The between the V. and VI. The main line operated chain conveyor was replaced by a new system from the ironworks Hasenclever & Sohn up to the 8th main line at −86 m above sea level. Siemens & Halske built a new power plant to meet the mine’s increased electricity needs. The systems went into operation in 1899.

After the Antonschacht , located 500 meters north-west of the Oppelschacht, was dropped in 1895, work began in 1902 to dismantle the shaft's safety pillar above the Tiefen Elbstolln .

On March 9, 1905, King Friedrich August visited the coal pits of the Döhlen basin. In addition to the Glückauf shaft in Bannewitz , he also visited the Oppel shaft and the Königin-Carola shaft.

On June 10, 1906 on the XII. Main line, from the Oppelschacht the breakthrough at a depth of 481.5 meters into the König-Georg-Schacht . The King Georg Schacht, although still in the depths, now served as a moving weather shaft .

In 1907 an electrically driven chain conveyor from the Petzold machine factory in Döhlen was installed between the 8th and the Xth main line at −126 m above sea level.

After the first cable car ride up to the XII. Main route took place on the König-Georg-Schacht, the workforce of the Oppelschacht was relocated to the König-Georg-Schacht.

After the on-site staff refused to work eight hours, the three-shift system was introduced on September 22, 1920.

In 1923 the old dewatering on the V main line was replaced by an electric twin high-pressure pump with a delivery head of 230 meters and an output of 2.7 m³ / h.

With the law of January 30, 1924, the Zauckerode coal works were transferred retrospectively to April 1, 1923 to the state corporation Aktiengesellschaft Sächsische Werke (ASW) under the name Steinkohlenwerk Freital . The chief miner A. Wolf rationalized the operation. All uneconomical mining sites were discontinued. The workforce was almost halved between 1924 and 1928, while coal output remained almost the same. Young miners in particular were moved to the Hirschfelde, Böhlen and Espenhain lignite mines. As a result, the operation of the König-Georg-Schacht was stopped. The remaining workers were distributed between the Oppelschacht and the Königin-Carola-Schacht. The remaining horse transport in the Oppelschacht was ended in 1925.

After the coal reserves in the Oppelschacht district had been exhausted, operations were stopped on June 30, 1927 and the shaft was filled. The workforce was transferred to the König-Georg-Schacht and operations resumed there.

In 1980, the mine was subsequently kept by the Dresden mountain rescue service .

Weather shaft

The Royal Coal Works sunk the weather shaft in 1883 at 190.43 m above sea level. It was located about 35 meters north of the production shaft. The Elbstolln depth was reached at 81.23 meters. The final depth was 84.40 meters. After the shaft had been bricked up, it was equipped in 1884 with a winter fan from the Barop mechanical engineering company with a diameter of 2.2 meters. In 1909 the fan was taken out of service. After the Albertschacht was closed in 1922, the weather shaft was needed again. Before restarting, the old fan was replaced by a Pelzer fan with a diameter of 1.46 meters. It was driven by a three-phase motor with 54 hp. At 480 revolutions per minute, the fan delivered 1200 m 3 of air per minute. From 1935 the weather management was reorganized. The shaft received a centrifugal fan with an output of 1000 m 3 air per minute. After the Kaiserschacht field was exposed, the amount of weather was no longer sufficient. In July 1953 the shaft received two two-stage axial fans of Soviet design with a diameter of 1.40 meters and an output of 700 m 3 / min each. They were installed one behind the other. The amount of weather increased to 2400 m 3 per minute. However, the old fan was only kept in reserve. After mining ceased in July 1959, the weather shaft was filled.

In 1979 the shaft was subsequently kept by the Dresden mountain rescue service.

Arthur-Teuchert-Schacht

In the time of need after the Second World War, the Freital hard coal works began to clear up the kept Oppelschachtes. The aim was to win the remaining shaft safety pillar of the Oppelschacht. After a short time it was found that the shaft tube was badly deformed and the effort to secure it was too great. Therefore, on August 1, 1946, at a distance of 45 meters from the main shaft, at 188.76 m above sea level, the depth of a new shaft began. At the end of January 1947, the 3.20 meter thick first seam was cut at 92 meters. In February 1947 the 0.35 meter thick second seam was cut at 98 meters and the 1.30 meter thick third seam in March at 103.40 meters. On March 8, 1947, the final depth was reached at 105 meters. The filling point of the 1st main line was posted at a depth of 93.72 meters. At a depth of 40.96 meters, a section to connect with the Tiefen Weißeritz adit was constructed. In 1947 coal production started there.

As of June 1, 1946, the plant was subordinated to the coal industry administration. On October 17, 1947, a lease agreement that was valid until December 31, 1948 was signed between the administration of the Saxony coal industry and the military unit, field post number 27304 ( Wismut AG ). Wismut leased the Oppelschacht with all buildings and facilities, as well as staff for 15,000 RM per month. The bismuth pays for all costs. The shaft was listed as shaft 94 . Responsible was the deputy head of administration, Lieutenant Colonel Georgi Wassiljewitsch Salimanow. On June 29, 1948, a contract was signed to return the shaft to the Freital coal works. completed. The administration buildings at Oppelschacht were still leased by the Wismut. From July 1, 1948, the plant belonged to VVB Steinkohle Zwickau as VEB Steinkohlenwerk Freital. On November 12, 1949, the Wismut AG property 06 and VVB Steinkohle Zwickau agreed to settle the outstanding claims against Wismut.

On October 20, 1948, the cutter Arthur Teuchert drove a “high-performance shift” based on the model of Adolf Hennecke , during which he exceeded the norm by 480 percent. In honor of Arthur Teuchert, the mine was henceforth called "Arthur-Teuchert-Schacht".

In 1953 the Oppelschacht was cleared from the Tiefen Elbstolln and put into operation as a blind shaft up to the fifth main line. The hoisting machine of shaft 2 Lower Revier should be used as the blind shaft hoisting machine. This was still in use there until September 1953. The fifth main line was cleared and the battery locomotive built by Siemens & Schuckert , which had been in use at Lichtloch 21 Tiefer Weißeritzstolln since 1943 , was used. By June 1955 the safety pillar of the Oppelschacht and a large area of the 3rd seam were dismantled.

In the 1950s, the mining only extended to a few remaining areas of poor quality and seam thickness, which had previously been excluded from extraction. After the final exhaustion of supplies in the mine field, production was stopped in May 1959. The shaft was dropped and backfilled by the end of September 1959.

In 1979 the shaft was subsequently kept by the Dresden mountain rescue service.

Todays situation

Of the daytime facilities, only the building of the former coal works is preserved today. The city of Freital re-uses it as a youth club and library.

In 1993 the Bergsicherung Freital dug an investigation shaft on the shaft site for the extension of the Tiefen Elbstolln into the pit field Gittersee ("Wismutstolln"). The headframe is still on the shaft site in 2015.

In 2001, the headframe of shaft 2 in Dresden-Gittersee was re-erected as a technical monument on the shaft area.

literature

- Heinrich Hartung, memorandum to celebrate the centenary of the Zauckerode Royal Coal Works. In the yearbook for mining and metallurgy in the Kingdom of Saxony. Craz & Gerlach Freiberg, 1906.

- Eberhard Gürtler, Klaus Gürtler: The coal mining in the Döhlen basin part 2 - shafts on the left of the Weißeritz. House of Homeland Freital, 1984.

- Saxon State Office for Environment and Geology / Sächsisches Oberbergamt (Hrsg.): The Döhlener basin near Dresden. Geology and Mining (= mining in Saxony . Volume 12 ). Freiberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-9811421-0-5 , pp. 202-203 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Description of the steam engine at www.albert-gieseler.de.

- ↑ Königliche Steinkohlenwerke Zauckerode (Kohlenschreiberei) ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the database MontE of the TU Freiberg.

Remarks

- ↑ Mines were referred to as firedamp pits when bad weather occurred. Which mine was designated as a firedamp pit was the responsibility of the responsible mining authority. Every mine in the district of the Dortmund Oberbergamt was regarded as a firedamp pit. (Source: NA Herold: Worker Protection in the Prussian Mountain Police Regulations. )