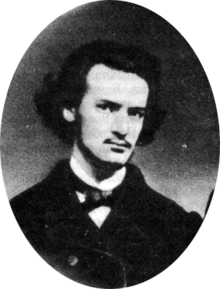

Arthur Benni

Arthur Wilhelm Benni , Russian Артур Иванович Бенни (born November 27, 1839 in Tomaszów Mazowiecki , † December 27, 1867 in Rome ) was a Polish revolutionary and freedom fighter. Worked for Hearts in London as a journalist and translator, Benni was granted British citizenship in 1857 . Sent from the heart to Russia as an employee of the newspaper Kolokol ("The Bell") , he was known there as a socialist and denounced as a spy. Leskow dealt with his stay in Russia in the novel Without Way Out (1865) and in the report A Mysterious Man (1872).

In the Battle of Mentana - Benni fought there under Garibaldi against General Chancellor and the Pope's French auxiliaries in early November 1867 - he was wounded and died as a result in Rome.

Life

Benni was born in the Łódź Voivodeship in Congress Poland (in the Petrikau Governorate ) as the son of the Protestant pastor Johann Jakob Benni (1800–1863), a Hebraist . Benni's mother, Mary White (1800–1874), who survived the son, was an Englishwoman. Only English was spoken at home. Arthur had two brothers - Hermann (1834–1900) and Carl (1843–1916) and two sisters - Anna and Marie (1836–1909). Hermann became a pastor and Carl later practiced as a doctor in Warsaw .

From 1849 Arthur attended the Polish grammar school in Petrikau . In England an uncle on his mother's side made it possible for him to train as an engineer. Arthur Benni came under the Ministry of Defense ; joined the engineering service at Woolwich Arsenal. On the island he got to know Herz, Bakunin , Ogarjow and Kelsijew at the end of 1858 and taught Herzens daughter Olga. In 1859 Benni gave up his well paid job and became private secretary to English aristocrats.

In preparation for the Polish uprising , Herzen sent Benni to the center of the rebellious Poles - to Paris . Benni studied medicine at the side of his brother Carl at the Sorbonne , where he also met Pyotr Dolgorukov, Turgenew , Tatjana Passek and Vladimir Tschuiko.

In May 1861 Benni returned to London to heart. At the end of June 1861 Benni went to Russia for four years on behalf of his heart. As an envoy from the heart, Benni was enthusiastically received in Saint Petersburg by the narodnik Andrei Nitschiporenko from the underground organization Land und Freiheit . The Pole with English roots was supposed to find out to what extent the Russians were ready to overthrow the monarchy. The topic of conversation was embarrassing even to the Petersburg folk. Even a trip with Nitschiporenko to the provinces, to Nizhny Novgorod , Moscow , to the Poltava governorate and to Mzensk zu Turgenew did not bring anything to the client, Herzen. Benni wanted access to the Russian people, but couldn't find him. Aksakow and Katkow rejected him in Moscow, but not the editor of the Russian language Leskow. When Benni returned to Saint Petersburg in September 1861, the rumor arose that the Briton was an agent of a foreign power.

To this day there are only conjectures as to who could have slandered Benni. For example, some historians accept Nichiporenko and Katkow as potential slanderers. The latter favored a Russian constitutional monarchy . Benni made a detour to Western Europe and spoke heartily in London and in Paris with Turgenev about the failure of his mission. Nikolai Vladimirov sent hearts to Russia. Active again in Russia, Benni tried to rehabilitate himself in 1862 through journalistic work on the short-lived newspaper Russian Truth . In vain, certain Russians had succeeded in denigrating Benni. Benni complained in a letter from May 1863 to the heart: The Polish rebels would not have wanted him in their ranks. Nevertheless, the "unwanted spy" visited Poland several times between 1862 and 1864; there said goodbye to his dying father. In 1864 Benni had his quietest and most productive time in Russia as editor of the Nordic bee . After the closure of this paper, Benni came to the debt tower - completely penniless - and was expelled from Russia in October 1865. He was previously involved in the 32-x trial against the aforementioned organization Land und Freiheit . The defendant Nichiporenko died during the three-year trial before the verdict was pronounced. Turgenev, also charged, was acquitted.

In 1866 Benni wrote for the British press in Switzerland ; for example for Anthony Trollopes The Fortnightly Review . Benni asked the Russian government in writing to return to his Polish homeland. Shuvalov did not respond to the repentant request. Benni then went to Italy as a correspondent . He joined Garibaldi, was wounded at Mentana and was captured. His infected hand had to be amputated in Rome. Benni died of gangrene .

Web links

- (Russian) Бенни, Артур Иванович - Benni, Artur Ivanovich

literature

- An enigmatic man. German by Hilde Angarowa . P. 492–608 in Eberhard Dieckmann (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes . Vol. 1: The Lady Macbeth from the Mtsensk district. Stories. 632 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1988 (1st edition), ISBN 3-352-00252-5

See also

Arthur Bennis Petersburg address was 29 Gorokhovaya Street.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russian Колокол - Kolokol

- ↑ Leskow, p. 496, 5th Zvu

- ↑ eng. Battle of Mentana

- ↑ Polish. Leonard Chodzko

- ↑ Russian Петроковская губерния - Petrikau Governorate

- ↑ eng. Woolwich Arsenal

- ↑ Russian Olga (1850–1952), married to Gabriel Monod since 1873

- ↑ Leskow, p. 496, 10. Zvu to p. 502, 6. Zvo

- ↑ Russian Долгоруков, Пётр Владимирович

- ↑ Russian Пассек, Татьяна Петровна

- ↑ Russian Чуйко, Владимир Викторович

- ↑ Russian Ничипоренко, Андрей Иванович

- ↑ Russian Земля и воля

- ↑ Russian Русская речь

- ↑ Russian Владимиров, Николай Михайлович

- ↑ Russian Русская правда

- ↑ Russian Северная пчела

- ↑ Russian process 32-x

- ↑ eng. The Fortnightly Review

- ↑ Russian Гороховая улица

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Benni, Arthur |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Benni, Arthur Wilhelm (full name); Бенни, Артур Иванович (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Polish revolutionary and freedom fighter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 27, 1839 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Tomaszów Mazowiecki |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 27, 1867 |

| Place of death | Rome |