Development plan (Germany)

In Germany, a development plan (B-Plan) regulates the type and manner of possible development on properties and the use of the areas that are to be kept free from development in this context.

In this case, a municipality stipulates as a statute by resolution of its municipality council which uses are permitted and to what extent on a certain municipality area. The development plan creates building rights and represents the binding land-use planning according to the second section of the Building Code (BauGB).

General

Unlike the zoning plan , which is drawn up for the entire municipality ( Section 5 (1), first sentence, BauGB) and forms a preparatory land-use plan, a development plan usually only covers part of the municipality, such as a group of properties or a district. The development plan must therefore set the limits of its spatial scope ( Section 9 (7) BauGB). In accordance with the principle of one-room layout , the scope of several development plans must not overlap.

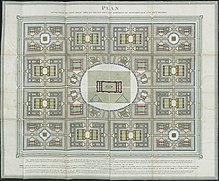

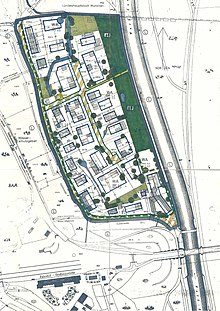

As a rule, the development plan consists of a plan drawing (Part A) and a textual part (Part B). For example, a development plan can also consist of just a textual part. A justification is not part of the articles of association, but is mandatory as part of the procedure, in which the objectives, purposes and essential effects of the development plan are set out. The environmental report ( Section 2a BauGB) forms a separate part of the justification .

The plan symbols are standardized according to the plan symbols ordinance in order to ensure general legibility; if necessary, however, further plan symbols can be developed. The textual determinations take place i. d. Usually based on the formulations in the Building Code (BauGB) and are therefore also largely standardized. The plan drawing is usually made on a scale of 1: 500, for larger plan areas also 1: 1000 to 1: 2500; The basis is the official real estate cadastre information system (ALKIS old: land map ), on which all of the plots affected by the planning as well as the adjacent parcels are to be identified. The planning area must be clearly delimited. This is usually done by sticking to existing property lines.

In order to understand the meaning and function of a development plan, it is important to know that when the Federal Building Act was first enacted, the legislature assumed that development in a country as densely populated as the Federal Republic of Germany would be based on a planned concept . In this respect, the development plan area remains the rule in the system of the law to this day. However, since it was and is to be assumed that not every part of the country will be planned in a binding manner, the legislature has made so-called plan-replacing regulations for areas that have not (yet) been planned by the municipalities. The legislature differentiates these areas that are not over-planned into so-called indoor and outdoor areas .

Sense and purpose of development planning

Due to the constitutionally guaranteed right of self-government of the municipalities , the planning sovereignty lies in the hands of the municipalities. Within the framework of the building code and the respective state building regulations, they can issue legally binding statutes (development plans) to control their urban development. The state building regulations form the legal basis for further design regulations (stipulations) in the development plans.

In this context, the term “urban development” should be pointed out in particular: only urban development goals, as defined in the BauGB and state building regulations, can and may be pursued with a development plan.

In § 1 BauGB task concept and principles are defined development planning (land use planning and development plan), namely "in the community to prepare the building and other use of land ... and conduct". It also states that the land-use plans are to be drawn up “as soon as and to the extent that it is necessary for urban development and order”. The decision about this lies with the municipality. So as long as the assessment of a building project indoors is possible without any problems in accordance with § 34 BauGB, a development plan can be dispensed with. If, however, tensions (e.g. conflicts of interest) are to be feared, tensions accumulate, or if an undesirable or negative urban development trend emerges, the zoning plan is the instrument for directing or maintaining development in certain directions. Settlement expansions (new development areas) using outdoor areas or larger projects in outdoor areas can only be implemented within the framework of a development plan procedure.

The development plan is to be developed from the land use plan , the preparatory land-use plan for the entire municipality (standard procedure).

According to the Building Code, a number of other aspects that must be taken into account during planning go hand in hand with urban development goals (see Section 1, Paragraph 5 of the BauGB):

- Sustainable development,

- Social, economic and environmental requirements,

- Responsibility towards future generations,

- Socially fair zoning that serves the common good,

- Humane environment,

- Protection and development of the natural foundations of life,

- Climate protection,

- Urban design,

- Building culture preservation and development of the place and landscape.

The objectives of spatial planning must be taken into account (Section 1 (4) BauGB). A catalog of eleven aspects (Section 1, Paragraph 6 of the BauGB), which must be particularly taken into account during planning, can be found

- Healthy living and working conditions,

- Social and cultural needs,

- Monument protection,

- Environmental protection concerns (very extensive)

- Business concerns

- Traffic concerns.

According to the Building Code, an important principle is that public and private interests must be weighed up fairly against each other in the course of planning. Incorrect or conscientious observance of this requirement can lead to partial or total invalidity of a development plan.

The essential purpose of the land-use planning is not yet described. Basically, all known facts that are relevant for the development and use of an area are put on paper. This includes all the interests involved and a large part of the legal regulations. Interests and laws are so diverse and extensive that there is hardly any leeway for free planning decisions; planning, as it is usually understood by laypeople, does not actually take place. Rather, it is a mediation process and the result is always a compromise (see review). An important aspect is that the planning gives a relatively high degree of reliability, which is not given in the unplanned interior area according to § 34 BauGB, and everyone can adjust to it.

Content of the development plan

The possible content of a development plan is finally regulated in § 9 BauGB.

Determinations

With regard to the type and extent of structural use according to § 9 Paragraph 1 No. 1 BauGB, according to According to Section 1 (3) of the Building Utilization Ordinance (BauNVO), typical building areas are established. The BauNVO then provides the detailed control for these determinations in a development plan. The stipulations of §§ 2 to 14 BauNVO become part of the development plan.

The type of structural use is mainly determined by the building areas designated in § 1 (2) BauNVO (small settlement areas, pure residential areas, general residential areas, special residential areas, village areas, mixed areas, core areas, commercial areas, industrial areas and special areas) with the corresponding (changeable) usage catalogs . The degree of structural use is according to § 16 BauNVO over the floor area number , the floor area number , the heights and the number of storeys fixed. This information is presented in building usage templates . Furthermore, in §§ 22, 23 BauNVO the construction methods and the building plot areas are defined and the permissibility of auxiliary buildings (ancillary facilities), parking spaces and garages regulated ( § 21a BauNVO). The essential stipulations for an area relate to the representation of the building areas, the areas that can be built over, the green areas, the traffic areas, the common areas, the areas for supply and disposal, for plantings, for usage regulations and measures (nature and landscape protection), agriculture - and forest areas. For the construction areas, the type and extent of use, the construction method and, in principle, the roof shape are specified.

The catalog of permissible determinations results from § 9 BauGB, for example

- Areas for public use as well as for sports and play facilities ( Section 9 (1) No. 5 BauGB),

- Areas that are to be kept free from development ( construction prohibited areas , Section 9 (1) No. 10 BauGB)

- Traffic areas as well as traffic areas for special purposes, such as pedestrian areas, areas for parking vehicles or parking bicycles ( Section 9 (1) No. 11 BauGB)

- Areas for waste and sewage disposal ( Section 9 Paragraph 1 No. 14 BauGB),

- Areas for the extraction of stones, earth and other mineral resources ( Section 9 Paragraph 1 No. 17 BauGB),

- Areas for agriculture and forest ( Section 9 Paragraph 1 No. 18 BauGB).

News takeover

In addition to the stipulations within the meaning of Section 9, Paragraph 1 of the BauGB, stipulations by other organizations (other usage regulations ) already made in accordance with other statutory provisions should be incorporated into the development plan for information by the municipality ( Section 9, Paragraph 6 of the BauGB).

Simple and qualified development plan

There is no legal obligation to include all regulations that are possible in a development plan. However, in order to represent the sole legal basis for the assessment of construction projects, at least four determinations must be made:

- The type of structural use

- The (permissible) degree of structural use

- The buildable land areas

- The local " traffic areas ".

If all four minimum stipulations have been made, one speaks of a “qualified development plan” in accordance with Section 30, Paragraph 1 of the Building Code, in which the admissibility of the project is finally regulated. Most of the development plans belong to this category.

If one of these four stipulations is missing, it is a “simple development plan” in accordance with Section 30 (3) of the BauGB. If no stipulations have been made, the assessment of the facts or construction project is then based on Section 34 ( indoors ) or Section 35 BauGB ( outdoors ). For the missing determination, the buildings in the immediate vicinity of the project are used for comparison.

Simple and qualified development plans go through the same procedural steps when they are drawn up. The decision in favor of a simple development plan does not mean that the procedure is "simplified" in the sense that procedural steps are omitted, e.g. with a simplified plan change procedure.

Transferred development plans

Many development plans in the Federal Republic of Germany were drawn up before 1960, before the Federal Building Act came into force for the first time. They continue to apply ( Section 233 (3) BauGB) as long as they do not contradict applicable law, i.e. their content could still be the subject of a development plan today. These development plans are called transferred development plans.

Establishment procedure

A zoning plan has significant, long-term effects on the availability, value and appearance of an area. Therefore, development plans are drawn up according to a procedure regulated in the BauGB, which is intended to ensure that all issues and problems are carefully recorded or recognized and properly weighed up during planning. Above all, the comprehensive participation of all those affected and the public should be ensured.

Each process step, i. H. the decision to draw up a development plan, the decision on early participation , the decision on the draft, the decision on the public display and participation of the public interest bodies, the decision on any changes and any further interpretation and participation that may be necessary, the decision on the The community committees weigh up the concerns and finally decide on the statutes.

The proposal for the decision to draw up a development plan (1st procedural step) usually comes from the administration (building / planning office); In the case of the special planning type of a “ project-related development plan ”, the initiative usually comes from a developer ( investor or building owner ). Both the installation decision according to Section 2 (1) of the BauGB as well as the resolution by the articles of association of the development plan at the end of the procedure in accordance with Section 10 (1) and (3) of the BauGB must be made known in the customary manner; after this publication, the building plan is legally binding.

The drafts are drawn up either by the planning office or a commissioned planning office. If possible, all obvious problems within the administration and possibly with some public bodies are clarified in the run-up to the decision on the listing or at least before the participation procedure. The decision for a building area is usually derived from the land use plan (FNP); As part of the FNP list, the building areas were at least roughly checked for their suitability. By clarifying all known problems as early as possible, the preparation procedure should be kept short in such a way that no changes after participation and therefore no further participation or no further resolution are required.

Environmental audit

The consideration of environmental protection concerns through an " environmental review " with the creation of a corresponding report is becoming increasingly important in the preparation of plans. In recent times, European law in particular has increasingly found its way into the planning process and now represents a significant part of the planning effort.

Section 2 (4) of the BauGB states that "the likely significant environmental impacts must be determined ..., described and evaluated". The structure of the environmental report to be prepared is listed in detail in the annex; The essential points are: a comprehensive inventory of the state of the environment, a prognosis of the development of this state with and without the implementation of the construction project (s), planned measures to avoid, reduce and compensate for the adverse effects, measures to monitor these effects. The results of this test must be taken into account in the weighing and are included in the planning.

According to § 13 BauGB, the planning community can also draw up a development plan in a “simplified” or “accelerated process” for the faster creation of living space without prior environmental assessment; in accordance with paragraph a indoors , until December 31, 2019 also for outdoors . However, this does not release the municipalities from the obligation to continue to have to consider all environmental and nature conservation concerns and from the responsibility to collect relevant data for a complete assessment: also to later recourse e.g. B. to be avoided according to the Environmental Damage Act .

No carbon dioxide limits may be set in development plans ; this applies to power plants and other larger companies that are subject to the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Act (TEHG). This was decided by the Federal Administrative Court in Leipzig on September 14, 2017. The ruling was justified by the fact that emissions are regulated by the TEHG and a fixed upper limit is not compatible with the law. According to this justification, the Leipzig judgment expressly does not apply to other pollutants , such as nitrogen oxides or fine dust .

Participation process

Participation procedures are used to designate the sections of the compilation procedure in which the general public as well as those affected, those responsible for public affairs, neighboring communities, etc. in particular are informed about the planning intentions and are asked to comment.

The bodies responsible for public affairs are state, semi-state (specialist) authorities and also private bodies whose opinion must be obtained because they are affected in some way by the planning. Examples of public bodies usually involved are regional associations , post offices , railways, telecommunications, trade supervisory authorities, chambers of agriculture , energy supply, carriers for lines and cables, transport companies , the Federal Railway Authority , churches, environmental protection associations, nature conservation authorities, the armed forces, the police, etc. who also have tasks or responsibilities in the planned area. They should submit their comments within one month and limit themselves to their area of responsibility. Those to be involved may be identified during a " scoping " appointment.

Depending on the administrative structure, public authorities may also be among the bodies responsible for public affairs, which are part of the administration in urban districts and are already involved in the internal community coordination, but are located in the district administration in smaller communities. There are also federal states in which the district and even the state administration holds offices that are also responsible for public affairs. These include, for example, land reorganization authorities, water authorities, health authorities, nature conservation authorities, building law authorities, forest authorities, agricultural authorities, trade supervisory authorities, traffic authorities, surveying authorities, road construction authorities, monument protection authorities, mining authorities, to name just the better known.

The BauGB prescribes two participations. These procedures take place in several steps and in different ways. In the first, "early" participation, the general goals and purposes, plan alternatives and effects of planning are taught. As a rule, this procedural step is carried out in such a way that invitations are made to a joint presentation and discussion in a meeting room. The discussion is recorded and there is still a few weeks to raise concerns and suggestions.

Public affairs agencies and neighboring communities are usually written to directly and provided with the necessary documents. The results of the early participation are included in the further planning process, provided the concerns are justified, legally justified or sensible (see criticism). The draft that was then developed and approved by the municipal council then goes into the participation process a second time. As part of the draft and interpretation decision , a decision is also made on the objections, concerns and suggestions received up to that point (see criticism). The dates are to be announced publicly in good time, as is customary for the location; the deadlines for the announcement and for the interpretations and statements are precisely regulated in § 3 and § 4 BauGB and must be strictly adhered to for an error-free planning process.

The planning documents as well as the environmental report and any associated reports (e.g. for noise) are usually displayed in the planning office, but often also in the town hall or a publicly accessible room in the town or district. As with early participation, the public-sector bodies and neighboring communities are written to directly.

Weighing process

Comments (objections, concerns, suggestions) are usually received in writing, but can be submitted orally for recording.

Comments are collected and viewed in preparation for the weighing up. Every single point of an opinion is dealt with. The concerns and suggestions are weighted, compared to the previous planning results and weighed against each other and against each other.

In many cases, the planning is even called into question, e.g. B. the need for a new building area. Often private problems, constraints or simply personal wishes are given as reasons for change requests. But if there is no legal basis to support these submissions, there is practically little chance that they will lead to a design change. Technical objections, however, can make plan adjustments necessary. These are almost always circumstances that have not yet been known or recognized and have therefore not been taken into account. However, since all known problems are usually carefully considered in the run-up to the preparation of the plan, this occurs relatively rarely.

In many cases, the statements are simply notes that must be observed.

The administration draws up an opinion on each point and suggests how this should be dealt with in the municipal council, be it that the planning is changed accordingly, that it is not changed or that the opinion is taken note of (weighing proposal). The municipal council is not obliged to accept these suggestions from the administration. However, it rarely happens that there is an opposing vote.

Process closure

After the balancing process, several paths can lead further:

- The statements lead to no or only minor changes and the building plan is adopted by the municipal council as a statute. The objections are either rejected or acknowledged (as a rule). (see review).

- The administration or the community council accepts objections and a change of plan becomes necessary. There may also be changes to the plan based on resolutions of the municipal council that have nothing to do with objections. However, this happens very rarely. If the change affects the main features of the planning, this leads to a completely new participation procedure. This happens relatively seldom and it is very rare that an objection is only accepted in the municipal council. If the main features are not affected and only certain persons or public bodies are affected by the change, a restricted participation procedure is sufficient. This occurs more often as part of a planning process. In this case, only those affected by the change will be heard again. After the second participation process, a new assessment may take place. Subsequently, a resolution of the articles of association is made in the municipal council.

If the administration makes a plan change before a decision-making process in the municipality, it saves a decision round in the various committees of the municipality and thus time.

The development plan is adopted as a municipal statute by the municipal council. The legally binding force (legal validity) occurs with the execution and public announcement . It should also be pointed out where and when the plan can be viewed by anyone. The municipality is obliged to inform all objectors of the result of the weighing and to explain why an objection or suggestion was not taken into account (see criticism).

The development plan can be applied before it comes into force if there are no objections after the participation phase that lead to a change in the plan. Building projects are then permissible and approvable according to § 33 BauGB, provided that all of the conditions mentioned have been met (in particular those of the secured development). A project cannot be rejected with a plan status according to § 33 BauGB on the basis of the development plan draft.

Change lock

Since the process of drawing up a development plan takes a longer period of time, which can include several years, before it comes into force, the municipality has the option of issuing a ban on changes to the planning area or parts of it. In this way, it can prevent construction projects from being carried out during the planning process that run counter to the planning or make it significantly more difficult. A change block is initially valid for two years by law ( Section 17 (1) sentence 1 BauGB). The municipality can extend this period by a third year if necessary. If special circumstances so require, the municipality can, with the approval of the higher administrative authority, extend the period of the ban on changes to a fourth year. However, from the point of view of property protection, this means that the maximum duration for a toleration of a change block to be accepted without compensation has been reached.

As an alternative to a change block, the municipality can postpone the decision on individual construction projects by up to one year.

Judicial review, judicial review

A development plan can be judicially checked against a building permit in the context of an action for rescission ( Section 42 (1), 1st alternative VwGO) (so-called incidence control ). This can be determined to be partially or completely null and void. Reasons for this indirect contestation of a B-plan are usually stipulations with which a person concerned does not agree. It is also possible that the deadline for submitting an application for a standards control has expired. This period is one year and begins when the development plan is announced. If the plan is worked out very thoroughly, errors in the determinations are rare; the chances that such will be found in court proceedings and found to be significant are therefore rather slim, but cannot be ruled out. The possible contestability of a determination is usually always taken into account during the preparation. The same applies to the assessment, which of course is also open to judicial review. The declaration of invalidity is only effective between the parties to the legal dispute (inter-partes effect).

In practice, the problem with a material and legally error-free set of plans is increasingly evident in the fact that, in addition to the relevant laws - which also change several times a year - in particular comments (BauGB, BauNVO) and current judgments (BVerwG; OVG / VGH) are to be observed. The courts naturally take into account the legal texts, but also the judgments that have since been issued. However, keeping yourself “up to date” on this requires a lot of time and a profound legal understanding. A planner therefore runs the risk of making incorrect decisions more and more frequently. Possible formal errors, such as those that may result from the planning procedure being implemented (e.g. too short a deadline for the design), should not go unmentioned here.

A development plan can also according to 47 VwGO are checked by the competent higher administrative court / administrative court within the framework of a norm review. There is one special feature of the B-Plan. In principle, all legal norms in Germany are void in the event of violations of applicable law. A validity despite illegality, as it is possible with administrative acts, is out of the question. This results from the rule of law in Article 20.3 of the Basic Law. Since the preparation of a B-plan is an enormous effort and the effects of certain procedural errors on the result are often minor, the BauGB makes an exception for the B-plans. According to §§ 214 ff. BauGB, not all formal errors are significant. Therefore only the violations listed there can lead to ineffectiveness. Other violations may make the plan. U. illegal, but not ineffective (void).

The main focus here is regularly on the review of the balancing decision of the municipality. In principle, only the normative body is entitled to weigh up the matter and, due to the separation of powers, can only be checked in court to a limited extent. However, the balancing procedure must also comply with the rule of law. A check for balancing errors is therefore an option. Errors recognized by the BVerwG (e.g. BVerwGE 34, 301 (309)) include:

- The deliberation failure: There is no proper weighing of public and private interests at all.

- The deliberation deficit: Not all of the significant issues have just been considered.

- The misjudgment: the importance of a single issue was misunderstood.

- The disproportionality of weighing up: Individual issues were weighted incorrectly among each other.

If the court finds a significant mistake, it will, unlike the action for avoidance, determine the ineffectiveness with effect for and against everyone (inter-omnes effect). The affected area is therefore an unplanned area from the start. The limitation of errors to considerable also applies in the context of the avoidance action. Therefore, the limitation rules of the BauGB (e.g. § 215 BauGB) also apply in the contestation process of the third party. Otherwise an incidence control would undermine the will of the legislature after two years from the entry into force. This circumstance also does not constitute a violation of the requirement of effective legal protection from Article 19, Paragraph 4 of the Basic Law, since legal protection is basically granted.

Approval practice for building applications / building applications

The assessment of building projects within the scope of development plans takes place exclusively according to their stipulations ( § 30 BauGB). In principle, a building project is eligible for approval if it does not contradict the provisions of the development plan; only the missing development, z. B. in a new development could be a delay.

Of great interest, of course, is how strictly the development plan is applied. There is also a system here. The plan can already provide for exceptions within the framework of its stipulations in accordance with Section 31 (1) BauGB, such as B. in the uses in the individual area types. These uses are not included in the general catalog of permissibility, because they have a certain potential for interference, which should first be examined, be it due to emissions, the use of space or the shape. If no conflicts are expected, these exceptions are usually granted.

Of greater importance for the approval practice, however, is the possibility of being able to exempt from the stipulations, as provided for in Section 31 (2) of the BauGB. This gives the building plan a certain degree of flexibility, which should make it easier to use. However, an exemption is subject to conditions:

In any case, the main features of the planning must not be affected and the deviation must be compatible with public concerns, taking into account the interests of the neighbors. According to the law, this must be accompanied by a third condition: either

- The necessity for reasons of the common good,

- The urban justifiability or

- The emergence of an unintended hardship.

Whether the basic features of a plan are affected by a change essentially depends on how much such basic features can be recognized in the stipulations and, above all, in the justification. An example: In a flat roof estate, the flat roof obviously represents a basic feature of the planning and no exemption could be granted for another roof shape. Neighboring interests play an important role in exemptions, since an important function of the development plan is the protection of legitimate expectations. Exemptions that would affect a neighbor, e.g. B. a higher construction height or exceeding the building window, cannot be granted without his consent. The necessity of an exemption for reasons of the common good concerns z. B. Utility facilities that were not planned in the planning area.

The urban development justifiability is relatively flexible in terms of design, but basically also depends on the planning concept: the stricter this is, the more significant the deviation.

Unintentional hardship would often arise due to circumstances that exist on an individual property, e.g. B. geological or topographical constraints that were not (sufficiently) taken into account when determining the construction window or the height of a building. The insistence on fixing could make building very difficult or even impossible.

Development plan changes

Often the urban development goals for the scope of a development plan develop over time or a specific project that is generally supported cannot be approved according to the applicable provisions of a fixed plan. Then there is the possibility of changing, adding to or completely canceling a development plan using the same procedure that is to be carried out for drawing up a plan (Section 1 (8) BauGB). Deviations from the stipulations that go beyond its set framework are not legally possible without changing the development plan. A change procedure basically runs like a list procedure. All procedural steps are to be adhered to, change procedures are often bypassed due to the effort involved and individual change requests rarely lead to plan changes. If there are several or frequent inquiries, there is a need and they are initiated. There may be development plans with third, fourth and more changes. If the main features of the original planning are not affected, the BauGB provides for the “simplified procedure” and some procedural steps are omitted or shortened (see Section 13 BauGB).

criticism

Citizens of the respective municipality can criticize the development plan. However, this is only up to a certain point in time when the participation options in the B-Plan process are available.

Citizen participation

All authorities and citizens involved in the planning (→ main article: citizen participation ) must be involved and heard. In this way, the interests of the individual are safeguarded in comparison with society, insofar as they are prescribed by law or were foreseeable. It is difficult to assert individual interests that go beyond this, whereby economic arguments for the use of a property are helpful for the interested party. One shortcoming is the late notification about the handling of comments. The legislature is only obliged to provide information after the procedure has been completed, so it is not possible to “influence by replying”. A rejected observer thus has the incalculable trip to court. A lack of flexibility or unwillingness of the administration to allow deviations from an existing development plan is often criticized. Such criticism approaches overlook the fact that the administration must ensure that all those affected are treated equally, including compliance with laws, including statutes.

Exceptions

The problem often arises that unproblematic building requests from an individual cannot be granted as an exception for reasons of equal treatment. The other builders also have to adhere to the guidelines, which (of course) should be a balanced representation. In addition, it must be assumed that the granting of an exemption represents a (negative) example for the neighborhood (“ precedent ”) and thus the original planning “gets out of hand”. On the other hand, plans made decades ago can no longer withstand contemporary requirements and findings, which is why plan changes are necessary.

Duration and effort

The planning time and the administrative effort are often criticized. The establishment of a plan is a democratic process that cannot be accelerated. The creation of simple development plans, even without problematic details, needs at least six months to pass through the offices for a complete process. Even project-related development plans, which were included in the BauGB to accelerate the planning process, can hardly be drawn up any faster. The vast majority of the planning time is needed for the participation phases and the political decision-making process. As a result, an (average) planning process usually takes one year from the drafting to the resolution of the articles of association. The time required depends on

- the size of the planning area,

- the number of property owners affected,

- the problems to be overcome, not least in the case of different interests,

- the environmental concerns,

- the administrative structure, such as the rhythm of the meetings of the bodies and the staffing of the individual offices.

See also

- Building Code

- Land-use planning

- Development plan (Austria)

- Zoning plan

- Area conservation claim

- Community planning

- Green area plan

- Skyscraper master plan in Frankfurt am Main

- Country planning in Germany

- Landscape plan

- Nullity dogma

- public building law (Germany)

- Spatial planning

- Spatial planning concept

- Regional planning

- urban planning

- Urban planning

literature

- Ronald Kunze, Hartmut Welters (Ed.): Building Code 2017. Text edition with introduction. BauGB - BauNVO - PlanZV - TA Lärm. Wekamedia, Kissing, 2017.

- Ronald Kunze, Hartmut Welters (Hrsg.): The practical handbook of building land use planning and urban planning law. Loose-leaf collection with ongoing updates. Wekamedia, Kissing, 1997-2017.

- Ernst , Zinkahn , Bielenberg , Krautzberger : BauGB commentary. CH Beck, Munich, 2008.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Development plan. Duden Law A – Z. Technical lexicon for studies, training and work. 2nd edition Mannheim: Bibliographisches Institut & FA Brockhaus 2010. Licensed edition Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education. quoted according to the development plan. Federal Agency for Civic Education, 2010, accessed on July 10, 2014 .

- ↑ JuraMagazin, Technologiezentrum Dortmund (TZDO): Keyword competition for planning approval

- ↑ Understand the accelerated procedure according to § 13a BauGB - planning practice - planning. Accessed April 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Accelerated development plan procedure in the interior ›Landesnaturschutzverband. Accessed April 30, 2020 (German).

- ↑ B-plan according to § 13b BauGB - difference to the offer development plan / service of the urban planning office Dr.-Ing. Johann Hartl. Accessed April 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Accelerated procedure according to §13b BauGB. Accessed April 30, 2020 (German).

- ↑ There are no carbon dioxide limits in the development plan. Retrieved October 24, 2017 .

- ↑ BVerwG, judgment of December 16, 1999 - 4 CN 7.98 = BVerwGE 110, 193 (incident check of a previous change in the development plan); BVerwG, decision of December 28, 2000 - 4 BN 32/00 = BauR 2001, 1066 (application deadline and incidence control I); BVerwG, decision of April 8, 2003 - 4 B 23/03 (application deadline and incident control II)

- ↑ District Office Neukölln: Can a development plan be changed?