Bolshevism

Bolshevism (origin of the word: Bolsheviks ; literally translated as' majorityists', a faction of the Social Democratic Workers' Party in Russia ) was initially a concept of the history of ideas that was used to describe the ideological- political doctrine created by Lenin and the interpretation of Marxism applied to Russian conditions . In political philosophy, Bolshevism corresponded to dialectical materialism , in its ideological and political meaning initially (until 1924) to Leninism , then later to Marxism-Leninism . Initially used specifically by the radical faction of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Russia (RSDLP), the Bolsheviks, as a self-designation, in the wake of the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1922, the image of "Bolshevism" was primarily shaped by declared "anti-Bolsheviks" and as a battle term against all Communist parties used in Europe . In Germany, the National Socialists in particular attached an anti-Semitic sign to the term , so that subsequently the terms “Bolshevik” and “Jew” were used almost synonymously for propaganda purposes. The Nazi chief ideologist Alfred Rosenberg , who witnessed the revolution of 1917 in Moscow as a student and published his anti-Semitic pamphlet Pest in Russia in 1922 , played a major role in establishing this attitude . In the context of the East-West conflict after the Second World War , Bolshevism as a political phenomenon and the term itself lost more and more meaning.

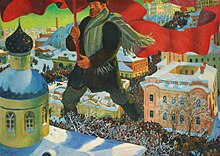

Russian revolution

Political ideology

Within the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDLP), a revolutionary, radical tendency emerged, the most important protagonist of which was Vladimir Ilyich Lenin . They soon called their own political views Bolshevism. The core of the ideology formed theories and political programs for the conquest of political power by a class-conscious militant elite of professional revolutionaries and the establishment of a “ dictatorship of the proletariat ”, combined with the socialist idea and the goal of a classless society . This voluntaristic approach, according to which the revolution must be brought about by the planning and action of the revolutionary elite, distinguishes Bolshevism from the thinking of Marx, who deterministically predicted an almost natural occurrence of the revolution with a corresponding development of the relations of production .

Historical background

The supporters of Lenin, who called for an imminent overthrow in Russia, won a majority ( Russian Большинство; bolshinstvo ) at the second party convention of the RSDLP in London , which is why they were called " Bolsheviks " ("majorityists"). The minority ( Russian меньшинство; Mensinstwo ), who focused on reforms, were referred to as " Mensheviks " ("minority people").

After the Russian Revolution , the faction name developed into a political battle term, for example in the political attitudes against Leninism . The Communist Party of the Soviet Union ( CPSU ), however, insisted on the term Bolshevism as its own name. Your party name carried the addition "Bolsheviks" until 1952.

Weimar Republic

Volkish movement

Bolshevism was fought both in the Weimar Republic and in the time of National Socialism by declared anti-communist opponents. With the establishment of the Anti-Bolshevism Fund , money from German entrepreneurs flowed into the private armies known as “ Freikorps ”, which fought the council movement across Germany with violence. This fund was used to finance anti-socialist and ethnic groups as well as the early National Socialist movements and parties.

National Socialists

Even in the early stages of the NSDAP in the Weimar Republic, the term Bolshevism was interpreted by the National Socialists under an anti-Semitic guise. In a leaflet published in 1918 and signed by Anton Drexler , it was said that Bolshevism was “Jewish fraud”. Alfred Rosenberg , who was also a founding member of the NSDAP and an avowed anti-Semite, later became the party's chief ideologist, was so impressed by the Russian Revolution that he considered a fight against "Bolshevism" to be necessary. In 1918 he ruled that only Great Britain could do this . Only one year later, in 1919, Rosenberg - as he wrote many years later - went to see Dietrich Eckart because he "wanted to write somehow about Bolshevism and the Jewish question". Both were guests of the Thule Society in 1919 . Rosenberg's first publications in the Völkischer Beobachter were on the topics of Zionism and " Jewish Bolshevism ". Under the programmatic title The Jewish Bolshevism , Rosenberg wrote the introduction to Eckart's work Die Gravegräber in 1921 , emphasizing that Jews were also in prominent positions among the Russian revolutionaries. Most of the people highlighted by Rosenberg did not practice their Judaism , and not a few of them later fell victim to the Stalinist excesses of cleansing.

The book Pest in Russia , published in 1922 by Alfred Rosenberg, contributed to the popularization and spread of anti-Bolshevik attitudes in connection with racial beliefs . The text is subtitled Bolshevism, Its Heads, Henchmen and Victims . Also due to the lack of quotations, Walter Laqueur stated in 1965 that this book “is noticeably lacking in learned information”. In addition, according to Laqueur, Rosenberg would have given “the Jews” an “excellent place” within the framework of the “demonology” of this book, which he illustrated with a total of 75 photographs. The “equation of Bolshevism and Judaism” made in this publication as well as the unconditional demand for opposition to Soviet Russia, not least, in the opinion of historians Bollmus and Zellhuber, “significantly” left an impression on Adolf Hitler . Due to Rosenberg's desire for the Germanization of the Soviet Union and the associated fear of being misunderstood with regard to its first publication, Rosenberg had the book republished in the 1930s, where he deleted or shortened entire text passages in this version. Up to then, however, nothing had changed in Rosenberg's fundamental attitude. In accordance with his racial ideological view, he expressed his belief in the book that “Bolshevism”, “the Jews” and “Judaism” endeavored to suppress “the Teutons” and the “Germanic spirit” . From this he deduced the political slogan at the end of the text that there would only be “one choice”, namely “annihilation or victory!” Since Adolf Hitler shared the views of his NSDAP chief ideologist Rosenberg on so-called “world Bolshevism”, This ideologically shaped enemy image of Bolshevism and the view that in view of the existential "threat" from "World Bolshevism" or "World Jewry" the "annihilation" of Jewish people was justified was spreading among the National Socialists . With this view, both Hitler and Rosenberg contributed to the formation of an intellectual breeding ground for the systematic murder of Jews in Europe. Although anti-Semitism was just as openly postulated in Germany (for example, the sentence “The Jews are our misfortune” was everywhere in the striker's showcases ), the expression “Jewish-Bolshevik” was mainly used by Alfred Rosenberg in the course of the Time established as an indissoluble double epithet in the vocabulary of Nazi propaganda . The term was also transferred to modern artists as cultural Bolshevism or music Bolshevism for defamation.

National Socialism

Institutionalization

After the “ seizure of power ” by the National Socialists in 1933, the image of “threatening world Bolshevism” was particularly widespread. This went hand in hand with the appointment of Alfred Rosenberg as the Führer’s commissioner for the supervision of the entire intellectual and ideological training of the NSDAP (DBFU) and the establishment of political institutions , such as the Foreign Policy Office (APA) von Rosenberg, whose main goal was the fight was against so-called "world Bolshevism". On January 21, 1934, on the basis of a suggestion by Robert Ley , Hitler awarded Rosenberg the title of DBFU and the associated mandate to spread his political ideology. In this position he had established connections to universities and the scientific community, as well as to the Wehrmacht, over hundreds of employees . Unwelcome scientists were severely restricted in their activities or pushed out of their offices. At the same time, he sponsored numerous publications of the writings of employees loyal to the regime who had committed themselves to his racial ideology. Through various liaisons, he had a direct influence on the National Socialist education and racial ideological upbringing of children and adolescents. B. via the head of the National Socialist Teachers 'Association , Fritz Wächter, with whom he founded a "Reichsschule der NSDAP" in October 1938 near Bayreuth as the umbrella organization for this teachers' association. This association of teachers had already trained 150,000 educators by the time the Reichsschule was founded. One of the most important liaisons to the Hitler Youth was Arthur Axmann . Even during the Second World War , he provided the Wehrmacht with hundreds of thousands of selected books, especially with racial ideology, anti-Bolshevik and violence glorifying writings.

War against the Soviet Union

Even before the German war of aggression against the Soviet Union, Rosenberg was secretly commissioned by Hitler on April 20, 1941 to deal with the central questions of the "Eastern Dream". Linked to this order was the establishment of Rosenberg's Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (RMfdbO). With regard to their racial ideologies, both Hitler and Rosenberg did not primarily fight against “the Russians”, but against “ World Jewry ”. The enemy image “ Jewish Bolshevism ” was the main theme under which all Nazi propaganda during the Eastern War stood. Immediately after the attack, the RMfdbO set up the two Reich Commissariats Ostland and Ukraine with independent civil and military administrations, with the aim of completely exterminating "Bolshevism" in the occupied territories and preventing those who were defined as "Germanic peoples" before the alleged " Bolshevik danger ”.

post war period

Since the late 1940s, the term Bolshevism was used by Anglo-American politicians as a collective term for the ideology of Leninism or Marxism-Leninism , or communism in general . In the post-war period, the frequency with which the term “Bolshevism” was used in political discourse decreased. Instead, the general term “communism” came to the fore. In the context of the two-sided ideologized East-West conflict , the image of “communism”, similar to the image of “Bolshevism” before 1945, was shaped to a large extent by anti-communism in the post-war period .

With the end of the East-West conflict in 1990, the internal claim that had been pursued politically within the CPSU as a trend-setting model for all forms of communism became obsolete. Since then, Bolshevism has become meaningless as a political phenomenon in international politics .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Herder Lexicon politics . With around 2000 keywords and over 140 graphics and tables, special edition for the State Center for Civic Education North Rhine-Westphalia, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1993, p. 157.

- ^ Ernst Piper : Alfred Rosenberg . Hitler's chief ideologist, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89667-148-0 , pp. 49 and 427.

- ↑ Andreas Wirsching , From World War to Civil War? , Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, p. 30; Jürgen Hartmann, Bernd Meyer and Birgit Oldopp, History of Political Ideas , Westdeutscher Verlag, Wiesbaden 2002, p. 212; John H. Kautsky, Marxism and Leninism. Different Ideologies , new edition, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick 2002, pp. 55 ff

- ↑ Quoted in: Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg . Hitler's chief ideologist, Munich 2005, p. 43. (Cited source: MSt Pol. Dir. M 6.697.)

- ^ Peter M. Manasse: Deported archives and libraries . The activity of the task force Rosenberg during the Second World War, St. Ingbert 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg: Last records , Göttingen 1955, p. 71 f. DNB (Please note that this document was published by his former colleague Heinrich Härtle . He had partially deleted passages, as a comparison with this book shows, for example: Serge Lang / Ernst von Schenck: Portrait einer Menschheitsverbrechers , St. Gallen 1947 , DNB )

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: The occult roots of National Socialism , Graz / Stuttgart, 1997, p. 132. (Source: Johannes Hering: Contributions to the history of the Thule Society , typed script from June 21, 1939, Federal Archives Koblenz, NS 26/865.)

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Germany and Russia , Frankfurt a. M. / Berlin 1965, p. 93.

- ^ A b Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg . Hitler's chief ideologist, Munich 2005, p. 63 f.

- ^ A b Walter Laqueur: Germany and Russia , Frankfurt a. M. / Berlin 1965, p. 95.

- ↑ Andreas Zellhuber: "Our administration is driving towards a catastrophe ..." The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories and German Occupation in the Soviet Union 1941–1945, Munich 2006, p. 32. (Reference to Bollmus: Amt Rosenberg . P. 224 f; O'Sullivan: Fear and Fascination . P. 282; Kuusisto: Rosenberg . P. 29 and Fest: Hitler . Pp. 169, 202 and 308.)

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg: Pest in Russia . Bolshevism, its heads, henchmen and victims, abbreviated by Georg Leibbrandt , 3rd edition, Munich 1937. DNB ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (4th ed., 1938; 5th ed., 1944.)

- ^ A b c Manfred Weißbecker: Alfred Rosenberg. "The anti-Semitic movement was only a protective measure ..." , in: Kurt Pätzold / Manfred Weißbecker (eds.): Steps to the gallows. Life paths before the Nuremberg judgments. 2nd edition, Leipzig 1999, p. 154 ff.

- ↑ Reinhard Bollmus, The Office Rosenberg and his opponents . Studies on the power struggle in the National Socialist system of rule, Munich 1970, p. 98. DNB

- ^ Cornelius Castoriadis: Society as an imaginary construction . Draft of a political philosophy, Frankfurt a. M. 1990, ISBN 3-518-28467-3 ; Peter L. Berger / Thomas Luckmann: The social construction of reality . A theory of the sociology of knowledge, Frankfurt a. M. 1989, ISBN 3-596-26623-8 .

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg . Hitler's chief ideologist, Munich 2005, pp. 49 and 427, ISBN 3-89667-148-0 .

- ↑ see: Eckhard John Musikbolschewismus - The politicization of music in Germany 1918–1938 , Stuttgart / Weimar: Metzler 1994, 437 pp.

- ^ The trial of the main war criminals before the International Military Court of Nuremberg November 14, 1945 - October 1, 1946 , Vol. V, Munich / Zurich 1984, p. 63.

- ↑ Jan-Pieter Barbian: "Literary Policy in the" Third Reich "". Institutions, competencies, fields of activity, Nördlingen 1995, ISBN 3-423-04668-6 .

- ^ The trial of the main war criminals before the International Military Court of Nuremberg November 14, 1945 - October 1, 1946 , Vol. XI, Munich / Zurich 1984, p. 525; Seppo Kuuisto: Alfred Rosenberg in National Socialist Foreign Policy 1933–1939 , Helsinki 1984, p. 117.

- ↑ Claus-Ekkehard Bärsch , The Political Religion of National Socialism , 2nd, completely revised. Ed., Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7705-3172-8 .

- ^ Ernst Piper : Alfred Rosenberg . Hitler's chief ideologist, Munich 2005, p. 518, ISBN 3-89667-148-0 .

- ^ The trial of the main war criminals before the International Military Court of Nuremberg November 14, 1945 - October 1, 1946 , Vol. V, Munich / Zurich 1984, p. 70; Martin Vogt: Autumn 1941 in the “Führer Headquarters” . Werner Koeppens reports to his Minister Alfred Rosenberg, Koblenz 2002, ISBN 3-89192-113-6 , p. 41 (source IMT, Vol. XXVI, Document 1028-PS, pp. 567-573).

- ^ Antonia Grunenberger: Antifaschismus - ein deutscher Mythos , Reinbek bei Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-499-13179-X .