Brooks-Sumner affair

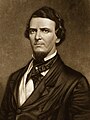

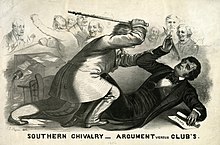

The Brooks-Sumner Affair ( English Brooks-Sumner Affair ; also Caning of Charles Sumner ) was an event in 1856 in the United States , which symbolizes the breakdown of a civilized discourse on the question of slavery . On May 22, 1856, Democratic Congressman Preston Brooks from South Carolina in the United States Senate struck Republican Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts with a walking stick and seriously injured him. Sumner, an abolitionist , had given a speech two days earlier in which he sharply attacked the slaveholders of the south and mentioned a relative of Brooks'.

background

On May 19 and 20, 1856, Sumner severely criticized the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 in his "Crime-against-Kansas" speech. In his extensive speech he had called for the immediate admission of Kansas Territory as a slavery-free state to the Union and then proceeded to accuse the "slave-democracy" (the predominance of slave owners) of the south:

“Not in any common lust for power did this uncommon tragedy have its origin. It is the rape of a virgin territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved desire for a new Slave State, hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of slavery in the National Government. "

Sumner then attacked the authors of the law, Senators Stephen A. Douglas from Illinois and Andrew Butler from South Carolina, saying, among other things:

“The senator from South Carolina has read many books of chivalry, and believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight — I mean the harlot, slavery. For her his tongue is always profuse in words. Let her be impeached in character, or any proposition made to shut her out from the extension of her wantonness, and no extravagance of manner or hardihood of assertion is then too great for this senator. "

Sumner indirectly compared Butler to Don Quixote and slavery to Dulcinea . Additionally, he made fun of Butler's impaired speech after a stroke:

“[He] touches nothing which he does not disfigure with error, sometimes of principle, sometimes of fact. He cannot open his mouth, but out there flies a blunder. "

According to Indian-American historian Manisha Sinha, Sumner had previously been ridiculed and insulted by both Douglas and Butler for his opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Butler had provoked Sumner in a very crude way with sexual allusions to black women and thereby used a common cliché that the abolitionists would recommend multiracial marriages.

However, sexually charged hints were also part of the abolitionists' repertoire. According to Williamjames Hoffer it is:

"Important to note the sexual imagery that recurred throughout the (Sumner's) oration, which was neither accidental nor without precedent. Abolitionists routinely accused slaveholders of maintaining slavery so that they could engage in forcible sexual relations with their slaves. "

Douglas said during Sumner's speech: "this damn fool is going to get himself killed by some other damn fool."

Preston Brooks , a cousin of Butler, was beside himself. He later testified that he wanted to challenge Sumner to a duel and that he had discussed the modalities with his colleague from the House of Representatives, Laurence M. Keitt , also from South Carolina. Keitt had then told him that a duel was in principle a matter between social equals and Sumner was no better than an ordinary drunkard, which was already evident from his hoarse pronunciation in his speech. Brooks said he had concluded that Sumner was not a gentleman and therefore deserved no honorable treatment. It seemed more appropriate for Keitt and Brooks to publicly humiliate Sumner by beating him with a stick in front of witnesses.

The day of the stick attack

Two days later, on the afternoon of May 22nd, Brooks entered the Senate Chamber with Keitt and another like-minded congressman Henry A. Edmundson . They waited until the galleries had emptied, paying particular attention to the fact that there were no more women in attendance to witness the events that followed. Brooks then approached Sumner when he was writing at his desk in the almost empty room and addressed him in a low, calm voice as follows:

“Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine. "

When Sumner was about to get up, Brooks hit him on the head with full force, using a thick, gutta-percha cane with a gold knob. The force of the blows made Sumner immediately lose his eyesight:

"I no longer saw my assailant, nor any other person or object in the room. What I did afterwards was done almost unconsciously, acting under the instincts of self-defense. "

Sumner went down and was wedged under his heavy, floor-mounted desk. His chair, which was pushed to the table, locked him in, and he was unable to respond with presence of mind and escape. Brooks kept beating him until Sumner was able to get to his feet and yank the table from its anchorage. He was now unable to see due to the heavy bleeding on his head. He stumbled down the aisle and tried to defend himself in vain with outspread arms. But that made him an easier target for Brooks, who kept slapping him on the head, face and upper body, "to the full extent of [my] power." Brooks didn't even stop after his stick broke; he continued to hit Sumner with the top piece with the gold pommel. When Sumner collapsed from the beating, Brooks held him in one hand and continued to hit him with the end of the stick in the other. By now, several other Senators and Congressmen had become aware of the scene and were trying to help Sumner, but were held back by Edmundson, who yelled at them to stay back, and Keitt, who threatenedly brandished his own stick and even drew his pistol.

Senator John J. Crittenden tried to intervene and begged Brooks not to kill Sumner. Senator Robert Toombs intervened on Crittenden's behalf by telling Keitt not to attack anyone who was not involved in the dispute, although Toombs later suggested he had no problem with Brooks' attack on Sumner and even approved of it.

Congressmen Ambrose S. Murray and Edwin B. Morgan were finally able to influence Brooks and get him to desist from his sacrifice, whereupon he quietly left the room. Murray then got help from a Senate bellboy and Sergeant at Arms , Dunning R. McNair . When Sumner had recovered and regained consciousness, the helpers led him into a dressing room. He received first medical care, among other things the wounds were stitched. With the help of Nathaniel P. Banks , Speaker of the House , and Senator Henry Wilson , Sumner was able to return to his quarters by carriage, where he continued to receive medical treatment. Brooks also needed medical attention before leaving the Capitol. He had met himself over his right eye in his rage while he was swinging the stick.

The stick Brooks had used, broken in several pieces, was left on the blood-smeared floor at the scene. Some of them were collected by Edmundson, who gave the pommel to Adam John Glossbrenner , the House Sergeant at Arms . This part was later exhibited at Boston's Old State House Museum . Members of the Southern Congress made rings from the other parts to wear on necklaces to show solidarity with Brooks. This one boasted:

"[The pieces of my cane] are begged for as sacred relics."

Aftermath

The episode showed the polarization of the USA in the clearest form, which had now even reached the Houses of Parliament. Sumner became a martyr in the north and Brooks a hero of the south. Many Northerners were outraged. The Cincinnati Gazette read:

"The South cannot tolerate free speech anywhere, and would stifle it in Washington with the bludgeon and the bowie-knife, as they are now trying to stifle it in Kansas by massacre, rapine, and murder."

William Cullen Bryant of the New York Evening Post asked:

“Has it come to this, that we must speak with bated breath in the presence of our Southern masters? ... Are we to be chastised as they chastise their slaves? Are we too, slaves, slaves for life, a target for their brutal blows, when we do not comport ourselves to please them? "

Thousands took to the streets to protest in Boston, Albany, Cleveland, Detroit, New Haven, New York and Providence. More than a million copies of Sumner's speech were distributed. Two weeks after the attack, Ralph Waldo Emerson described the apparent division in American society as follows:

"I do not see how a barbarous community and a civilized community can constitute one state. I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom. "

In the newspapers of the southern states, however, Brooks was celebrated. The Richmond Enquirer wrote in its opinion column that Sumner deserved to be beaten "every morning" and praised the attack as "good in conception, better in execution, and best of all in consequences". The "vulgar abolitionists" in the Senate have been running around without bridles for too long and have to be flogged until they are surrendered. Southerners sent Brooks hundreds of new walking sticks. One of them read: "Hit him again."

House member Anson Burlingame publicly humiliated Brooks by inciting him to demand a duel, only to then set terms that intimidated Brooks into withdrawing. Burlingame, an excellent marksman, as the invited party, had the choice of weapons and the place of duel. He chose rifles as weapons and the Canadian side of Niagara Falls as the place where the US ban on duels did not apply. Brooks then withdrew his request on the grounds that he did not want to expose himself to a trip through the hostile northern states.

Brooks also threatened Senator Henry Wilson, Sumner's colleague from Massachusetts. Wilson called the attack on Sumner "brutal, murderous, and cowardly" and Brooks challenged him to a duel. Wilson refused on the grounds that he could not promise by either legal standards or personal conviction, and duels were a relic from the days of barbarism. When rumors surfaced that Brooks would attack him like Sumner in the Senate, Wilson replied to the press: "I have sought no controversy, and I seek none, but I shall go where duty requires, uninfluenced by threats of any kind." Wilson went on Brooks's threats had no effect on his Senate duties.

The historian William Gienapp concluded that Brooks' attack was of paramount importance for the development of the Republican Party from a vying party to a strong political force (“of critical importance in transforming the struggling Republican party into a major political force . ")

Southerners made fun of Sumner, claiming he was faking his injuries. They said Brooks' stick wasn't tough enough to cause serious injury. They also claimed that Brooks had hit Sumner no more than a few times and that he did not hit hard enough to cause permanent damage. In fact, Sumner had suffered a head trauma that caused him severe and chronic pain that remained with him for the rest of his life. He spent three years convalescing before resuming his Senate seat.

Brooks claimed that he had no intention of killing Sumner or he would have used a different instrument. In a speech to the House of Representatives in which he defended his act, he said that he had not wanted to show any disregard for the Senate or Congress. He was taken into custody for the attack, tried in a District of Columbia court , and fined $ 300. A motion to expel him from the House of Representatives failed, but he resigned on July 15 to stand for re-election. The August 1st election turned out to be in his favor, and Brooks quickly returned to office. In another new election later that year he was re-elected but succumbed to illness before the new term began.

Keitt was warned by the House of Representatives. He resigned in protest but, like Brooks, was re-elected within a month and with a large majority. In 1858, he tried to strangle Republican Congressman Galusha A. Grow of Pennsylvania in an argument on the floor of the house. An attempt to caution Edmundson too failed to win a majority in the House.

In the elections of 1856, the still new Republican Party achieved gains with the double slogans "Bleeding Kansas" and "Bleeding Sumner" and capitalized on the possibility of branding the Democrats as extremists. Although the Democrats won the presidential election of 1856 and increased their majority in the House of Representatives, the Republicans in the States and in the Senate made some dramatic progress. The violence in Kansas and the attack on Sumner helped the Republicans weld themselves together as a party, an important step towards their victory in the next presidential election in 1860.

During the closing session in late 1856, Brooks made a speech calling for Kansas to be accepted as a state itself with a constitution that excluded slavery. His indulgent tone impressed Northerners and disappointed supporters of slavery.

Web links

- The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner (US Senate website)

- C-SPAN Q&A interview with Stephen Puleo about his book The Caning: The Assault that Drove America to Civil War , June 21, 2015

Individual evidence

- ^ The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner . United States Senate . Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ Michael William Pfau: Time, Tropes, and Textuality: Reading Republicanism in Charles Sumner's 'Crime Against Kansas' . In: Rhetoric & Public Affairs . 6, No. 3, 2003, pp. 385-413, cited from p. 393. doi : 10.1353 / rap.2003.0070 .

- ↑ Kenneth Davis: Don't know much about the Civil War: everything you need to know about America's greatest conflict but never learned . Harper, New York 1996-2011.

- ↑ Pat Hendrix: Murder and Mayhem in the Holy City . History Press, Charleston, SC 2006, ISBN 978-1-59629-162-1 , p. 50.

- ↑ Manisha Sinha: The Caning of Charles Sumner: Slavery, Race and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War . In: Journal of the Early Republic . 23, No. 2, Summer 2003, pp. 233-262. doi : 10.2307 / 3125037 .

- ↑ William James Hull Hoffer: The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2010, ISBN 978-0-8018-9468-8 , p. 62.

- ↑ Eric H. Walther: The Shattering of the Union: America in the 1850s . SR Books, Lanham, MD 2004, ISBN 978-0-8420-2799-1 , p. 97.

- ↑ Michael Daigh: John Brown in Memory and Myth . McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC 2015, ISBN 978-0-7864-9617-4 , p. 113.

- ↑ Eric H. Walther: The Shattering of the Union: America in the 1850s . SR Books, Lanham, MD 2004, ISBN 978-0-8420-2799-1 , p. 98.

- ^ Michael S. Green: Politics and America in Crisis: The Coming of the Civil War . ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA 2010, ISBN 978-0-313-08174-3 , p. 94.

- ^ Henry David Thoreau: Lewis Hyde (Ed.): The Essays of Henry D. Thoreau: Selected and Edited by Lewis Hyde . North Point Press, New York 2002, ISBN 978-0-86547-585-4 , pp. Xliii.

- ↑ Stephen Puleo: The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War . Westholme Publishing, Yardley, PA 2013, ISBN 978-1-59416-187-2 , p. 112.

- ^ Civil War Times Illustrated , Volume vol 11.Historical Times Incorporated, Harrisburg, PA 1972, p. 37.

- ↑ Eric H. Walther: The Shattering of the Union: America in the 1850s . SR Books, Lanham, MD 2004, ISBN 978-0-8420-2799-1 , p. 99.

- ^ Michael S. Green: Politics and America in Crisis: The Coming of the Civil War . ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA 2010, ISBN 978-0-275-99095-4 , p. 99.

- ^ Neil Kagan: Eyewitness to the Civil War: The Complete History from Secession to Reconstruction . National Geographic, Washington, DC 2006, ISBN 978-0-7922-6206-0 , p. 21.

- ^ Rachel A. Shelden: Washington Brotherhood: Politics, Social Life, and the Coming of the Civil War . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC 2013, ISBN 978-1-4696-1085-6 , p. 122.

- ↑ Mark Scroggins: Robert Toombs: The Civil Wars of a United States Senator and Confederate General . McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC 2011, ISBN 978-0-7864-6363-3 , p. 91.

- ↑ RM Devens: Assault on the Hon. Charles Sumner, by the Hon. Preston S. Brooks . In: Hugh Herron (Ed.): American Progress . , Chicago, IL1882, p. 438.

- ↑ LD Campbell: US House of Representatives Report 182, 34th Congress, 1st Session: Select Committee Report, Alleged Assault upon Senator Sumner . US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC June 2, 1856, pp. 64-65.

- ↑ William James Hull Hoffer: The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2010, ISBN 978-0-8018-9468-8 , p. 9.

- ^ AJ Langguth: After Lincoln: How the North Won the Civil War and Lost the Peace . Simon & Schuster, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-4516-1732-0 , p. 13.

- ^ Charles A. Phelps: Life and Public Services of Ulysses S. Grant (Internet Archive) . Lee and Shepard, New York 1872, p. 362.

- ↑ William James Hull Hoffer: The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2010, ISBN 978-0-8018-9468-8 , pp. 8-11.

- ↑ JD Dickey: Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, DC . Globe Pequot Press, Guilford, CT 2014, ISBN 978-0-7627-8701-2 , p. 141.

- ^ John C. Rives: The Congressional Globe . John C. Rives, Washington, DC June 2, 1856, p. 1362.

- ↑ # 7 Raising Cane . EMN: Military History Now. May 5, 2015.

- ↑ Stephen Puleo: The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War . Westholme Publishing, Yardley, PA 2013, ISBN 978-1-59416-187-2 , pp. 114 f ..

- ↑ James M. McPherson: Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era . Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 9780195168952 , p. 150.

- ^ William E. Gienapp: The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856 . Oxford University Press, 1988, ISBN 9780198021148 , p. 359.

- ↑ Stephen Puleo: The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War . Westholme Publishing, Yardley, PA 2013, ISBN 978-1-59416-187-2 , pp. 36 f ..

- ↑ John J. Palmer: The Caning Affair . In: The Western Democrat , June 3, 1856, p. 3.

- ^ Ovando James Hollister: Life of Schuyler Colfax (Internet Archive) . Funk & Wagnalls, New York 1886, p. 98.

- ↑ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography , Volume vol. IV. James T. White & Company, New York 1895, p. 14.

- ^ Paul F. Boller: Presidential Campaigns: From George Washington to George W. Bush . Oxford University Press, New York 2004, ISBN 978-0-19-516715-3 , p. 96.

- ↑ Senator Wilson and Mr. Brooks . In: Daily Courier , June 4, 1856, p. 3.

- ^ Sally A. Merrill: Cumberland and the Slavery Issue . Prince Memorial Library. October 27, 2017.

- ^ William E. Gienapp: The Crime Against Sumner: The Caning of Charles Sumner and the Rise of the Republican Party . In: Civil War History . 25, No. 3, 1979, pp. 218-45. doi : 10.1353 / cwh.1979.0005 .

- ^ Thomas G. Mitchell: Antislavery Politics in Antebellum and Civil War America . Praeger, Westport, CT 2007, ISBN 978-0-275-99168-5 , p. 95.

- ^ David Herbert Donald: Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War . Sourcebooks, Inc., Naperville, IL 2009, p. 259.

- ↑ Thomas G. Mitchell: Anti-Slavery Politics in Antebellum and Civil War America 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Todd Brewster: Lincoln's Gamble . Simon & Schuster, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-4516-9386-7 , pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Benson J. Lossing, Woodrow Wilson: Harper's Encyclopedia of United States History from 458 AD to 1909 , Volume vol. 1. Harper & Brothers, New York 1905, p. 409.

- ^ Outrage in the United States Senate: Senator Sumner, of Massachusetts, Knocked Down and Beaten till Insensible by Mr. Brooks, of South Carolina (ProQuest Archiver) . In: The Baltimore Sun , May 23, 1856, p. 1.

- ↑ William James Hull Hoffer: The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2010, ISBN 978-0-8018-9468-8 , p. 83.

- ↑ James Grant Wilson, John Fiske: Appletons' Cyclopaedia of American Biography , Volume vol. V, Pickering – Sumter. D. Appleton and Company, New York 1898, p. 747.

- ^ Akhil Reed Amar: America's Constitution: A Biography (Google Books) . Random House, New York 2006, ISBN 978-0-8129-7272-6 , p. 372.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker: American Civil War: A State-by-State Encyclopedia , Volume vol. 1. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA 2015, ISBN 978-1-59884-528-0 , p. 382.

- ^ A Biographical Congressional Directory (Internet Archive) . US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 1913, p. 502.

- ↑ Robert D. Ilisevich: Galusha A. Grow: The People's Candidate (Internet Archive) . University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh 1988, ISBN 978-0-8229-3606-0 , p. 124 .

- ^ Robert Draper: Do Not Ask What Good We Do: Inside the US House of Representatives . Simon & Schuster, New York 2012, ISBN 978-1-4516-4208-7 , p. 155.

- ^ Transactions of the Kansas State Historical Society , Volume vol. 7. WY Morgan, Topeka, KS 1902, p. 424.

- ^ Charles Sumner: The Works of Charles Sumner , Volume vol. IV. Lee & Shepard, Boston 1873, p. 266.

- ^ David Herbert Donald: Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War . SourceBooks, Inc., Naperville, IL 2009, p. 252.

- ^ The Panic of 1857 and the Coming of the Civil War . Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, LA 1987, ISBN 9780807124925 , p. 258.

- ↑ Stephen Puleo: The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War . Westholme Publishing, Yardley, PA 2013, ISBN 978-1-59416-187-2 , p. 204.

- ^ Robert Neil Mathis: Preston Smith Brooks: The Man and His Image . In: South Carolina Historical Society (Ed.): South Carolina Historical Magazine . 79, Charleston, SC, October 1978, p. 308. "In a deliberate, unemotional address he unexpectedly announced that he was prepared to vote for the admission of Kansas" even with a constitution rejecting slavery. ""