Don Quixote

Don Quixote [ ˈdoŋ kiˈxɔte ] ( Don Quixote in old spelling; Don Quixote [ kiˈʃɔt ] in French orthography, partly also used in the German-speaking area) is the general term for the Spanish-language novel El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes , translated The ingenious junker Don Quixote von der Mancha , and at the same time the name of the protagonist . The first part was published in 1605, the second in 1615 under the title Segunda parte del ingenioso caballero don Quixote de la Mancha .

Don Quixote is a reader addicted to his chivalric novels, who seems unable to distinguish between fiction and truth. He considers himself a proud knight who is supposedly fated to face one daring adventure after the next. He gets on his rickety horse Rosinante and fights against windmills, among other things. The apparently naive squire Sancho Panza (also: Sancho Panza) rides faithfully at his side and tries to protect his master from worse calamities. Most of the episodes end with Don Quixote being beaten up and appearing with little glory as the “knight of the sad figure”. In the second part, presented in 1615, the - still impoverished - country nobleman Don Quixote became a literary celebrity.

content

Grandville : Don Quixote's Struggle with the Red Wine Skins (1848)

|

Grandville : Don Quixote's Adventure with the Pilgrims on the Penance (1848)

|

Honoré Daumier : Don Quixote on his horse Rosinante (around 1868)

|

Opening movement of the novel

"En un lugar de la Mancha, de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme, no ha mucho tiempo que vivía un hidalgo de los de lanza en astillero, adarga antigua, rocín flaco y galgo corredor."

"In a place of La Mancha, whose name I do not want to remember, lived not long ago a Hidalgo , one of those that a spear in the lance rack, an old buckler [an old sign], a scrawny nag and a greyhound for Have hunting. "

First part

Alonso Quijano, a small country nobility, lives “somewhere” in the Mancha in Spain . He has read almost all chivalric novels whose events he considers to be absolutely true from a certain moment on. This reading has taken him so far from reality that one day he wants to become a “knight errant” himself, in order to plunge death-defyingly into adventures and dangers, to fight injustice and to attach eternal glory to his name. He changes this to Don Quixote and gives his old skinny horse the name Rosinante ( Rocinante , Spanish rocín “horse” and antes “before” or “previous”) with the double meaning “previously an ordinary horse, (now) all horses previous ". A peasant girl whom he once secretly adored in his youth, but has never seen again since, he chooses - following his literary models - to be the mistress of his heart and melodiously calls her Dulcinea von Toboso (from dulce "sweet"). He will never see her during the novel.

He cleans a rust-eaten armor that has been preserved from his ancestors, converts a simple balaclava with cardboard and metal into a helmet and goes on adventures. Everything that he encounters he associates with knighthood , although this has been extinct for generations. A simple tavern appears to him as a citadel, the prostitutes will damsels and the host to Castellan , of which he gave the accolade asks - and receives. In almost every adventure he takes a beating. He is finally brought home completely smashed. A barber and the village priest organize an autodafé ( book burning ) in Don Quixote's house , to which - with the exception of Amadís de Gaula and Tirant lo Blanc - all of his chivalric novels fall victim. But Don Quixote decides to go for a new ride and accepts a farmer as his squire, who will accompany him from then on. His name is Sancho Panza ( panza can be understood as “belly” or “belly”). He is the opposite of his knight in every respect: He is long, skinny, spun in idealistic dreams, supposedly fearless - Sancho, on the other hand, is small, fat, practical and thinking with common sense , fearful. He sees through the follies of his master, but still obeys him. Don Quixote, according to the instructions in the chivalric novels and as his squire, promised him the governorship of an island. This temptation binds Sancho to his master in spite of all reservations.

Accompanied by his assistant, Don Quixote sets out on his second ride. This is where the deeds for which the novel is famous take place. Don Quixote fights against windmills, which appear to him to be giants (the expression “ fight against windmills ” goes back to this story), attacks dusty flocks of mutton, which for him seem to be mighty armies, chases a barber's shaving bowl, which for him the Mambrin's helmet represents a "bloody" battle with a few bottles of red wine and the like. At the end of such adventures, Don Quixote is often terribly beaten up by his adversaries or is harmed in some other way. Sancho Panza always points out to his master the discrepancy between his imagination and reality. For Don Quixote, however, it is based on the deception of powerful sorcerers who are hostile to him. He believes, for example, that these have enchanted the giants in windmills. At the suggestion of his squire, Don Quixote gives himself the nickname "The Knight of the Sad Shape".

Again, at the end of the day, it is the barber and the village priest, supported by a canon , who outsmart Don Quixote and bring him back to his home in a cage on an ox cart.

Numerous self-contained episodes are woven into the entire narrative, the most extensive of which is the novella of the brooding for-witty .

Second part

The work became a bestseller right after it was first published at the beginning of 1605 - just a few weeks later, three pirated prints appeared . Cervantes did not finish the second part until ten years later (1615) after - spurred on by the success of the first book - another writer under the name Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda had written an unofficial sequel that was not approved by Cervantes. Although there are only a few weeks between the end of the first and the beginning of the second part within the novel's plot, the narrative claims that the first part is already published and known to a wide audience. The same goes for the book of Avellaneda.

The two heroes go on adventures again, which usually end more lightly than in the first part. This is also because Don Quixote repeatedly comes across people who already know him because they have read the first part of the book and therefore know who they are dealing with.

Don Quixote encounters a transport of two wild, hungry lions. He urges the keeper to open the cage to face the beasts to fight. Despite all objections, he finally opens a cage. The lion stretches briefly, then lies down again and just sticks out his bottom towards Don Quixote. He sees the adventure as over and goes by the nickname “Knight of the Lions”.

On his way to the tournament in Saragossa, Don Quixote meets a duke and his wife who have read Cervantes' book with great enthusiasm. They invite the knight and his stable master into their residence and stage jokes for weeks to amuse themselves at the folly of the Quixote. The Duke also granted Sancho Panza's wish for an island. He appoints Sancho as governor of a town. Sancho "rules" with astonishing wisdom and passes Solomonic judgments , but after ten days he is fed up with governorship and returns to Don Quixote. They are now moving to Barcelona , where Don Quixote meets the "Knight of the Silver Moon". This challenges him to the tournament , throws him from his horse and, in his knightly honor, obliges him to return to his homeland. Behind the name “Knight of the Silver Moon” hides a friend of the village priest and the barber, who in this way forces Don Quixote to return home.

Just a few days after his return, Don Quixote developed a fever. On his deathbed he suddenly realizes the nonsense of the books of knights and complains that this insight came so late to him. With that, his life and the book end.

background

The novels of chivalry were among the most popular readings of the late Middle Ages , especially the novel Amadis of Gaul . Growing demand from the readership led to a flood of new sequels depicting increasingly fantastic, unbelievable adventures that - according to the educated people of the time - clouded the minds of readers.

This is where the author starts. His Don Quixote is not only intended to parody the chivalric novels , but also to show how excessive reading of them is mind-numbing. Cervantes claims to have taken the story itself from the writing of a (fictional) Arabic historian, Cide Hamete Benengeli, whose Arabic name contains a “deer” as well as “Cervantes”.

The hometown of Don Quixote

According to a popular theory, Cervantes alludes in the opening sentence to the place Argamasilla de Alba in the province of Ciudad Real , where he is said to have spent some time in prison, but this is not proven.

According to a study by the Complutense University in Madrid , due to its geographical location, Villanueva de los Infantes, a good 40 km south of Argamasilla de Alba, is the starting point for Don Quixote's rides.

In the last chapter of the second part, Cervantes writes that the fictional narrator appearing in the novel did not name the hometown of the protagonist,

«… Por dejar que todas las villas y lugares de la Mancha contend these entre sí por ahijársele y tenérsele por suyo, como contendieron las siete ciudades de Grecia por Homero."

"... to enable all the towns and villages of the Mancha to compete as to which place may claim him as his son and count among his own, just as those seven cities of Greece once fought over Homer."

importance

The ingenious Junker Don Quixote von der Mancha is one of the most influential and well-known books in world literature , especially with its importance in the Spanish-speaking world. The literary figure of the knight Don Quixote gave rise to numerous literary ideas soon after it was created by Cervantes, who probably originally wanted to write a short, bitter parody of the then popular knight stories. But only on the surface is Don Quixote such a parody. The Autodafé chapter is a quick slice of contemporary Romance literature . As with his contemporary William Shakespeare , the central theme of Cervantes is the question of what is reality or dream in our environment, i.e. the conflict between reality and ideal. According to Cervantes, neither the senses nor the words can be trusted, even names become ambiguous. The readers should also doubt whether they have to classify the hero as a weird idealist or a ridiculous fool. Cervantes does not resolve this ambiguity , which is why there are contrary interpretations of Quixote's madness in literary studies. On the one hand, this can be understood as a conscious game in which Quijote copies the madness of reality and holds up a mirror to the world. On the other hand, it can be understood as an actual mental illness, for which there are different psychoanalytic interpretations.

Erich Auerbach regards Don Quixote's foolishness as neither tragic nor the novel socially critical; it is a comedy about the conflict between fantasy and common sense. Don Quixote's behavior becomes ridiculous in the face of a "well-founded reality" that is not questioned by the author either. The characters with whom Don Quixote collides are only strengthened by his behavior in their healthy sense of the realities.

Finally, in the second volume, the fool becomes a wise man, while his dumb companion develops into a second Solomon .

interpretation

A central element of the novel is playing with illusions : in the leitmotif, strongly oriented towards the figure of Dulcinea, Cervantes repeatedly points out conditions under which people believe unbelievable things. Cervante's novel is, as it were, an eulogy for friendship. Sancho Panza is not primarily his master's servant and squire, but rather a comrade and companion. He is friendly to Don Quixote and turns out to be very lucky for the only self-proclaimed and inglorious hero. This happens even though the two make a very unequal pair. While one comes from the old, albeit impoverished, nobility - tall and skinny and spiritualized through and through - the one represented by a small, rounded stature and from the "people" is a plebeian and enthusiastic advocate of all physical pleasures to them especially eating and drinking. One protagonist represents the world of ideas, the other perceives reality and represents its principle, so to speak. The two have to pull themselves together again and again and in long conversations a friendship develops in both. Don Quixote's megalomania, his often tragic obsession, are softened thanks to Sancho Pansa's relativizing humor, humanity is returned to him and Sancho Panza saves a friend from squandering all sympathies - also with the reader. The high class barriers at the time the novel was written are questioned and a society of togetherness is advertised as being consoling and bringing happiness.

Over the centuries, Don Quixote has experienced a variety of interpretations : the work was seen not only as a parody of the chivalric novels of the time, but also as a representation of heroic idealism , as a treatise on the exclusion of the author himself or as a criticism of Spanish imperialism . For example, Vladimir Nabokov and José Ortega y Gasset have written something illuminating about this character and its history.

Some literary scholars - above all Leandro Rodríguez - recognized in numerous details of the plot allusions to the problems that Conversos - families of baptized Jews - were exposed to in Spanish society in the 16th century. Clear allusions and a Talmud QUOTE in Don Quixote also led to the - but not secured - thesis that Cervantes could even come from a family of conversos.

There is no consensus in literary studies about the actual message of the novel.

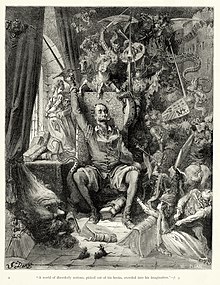

Many artists have made paintings or illustrations of Don Quixote and his stories, including Grandville , Alfred Kubin , Honoré Daumier , Adolph Schroedter , Gustave Doré , Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso . Among other things, Dalí drew the illustrations for an edition of Don Quixote , the original of which can be seen in the Dalí Museum in Paris.

Fight against the windmills

Don Quixote's battle against the windmills is the most famous episode of the novel. It only plays a subordinate role in the original, but is central to most modern adaptations of the material. According to a common interpretation, the 17th century was fascinated by this hopeless struggle of the gracious gentleman against the merciless machine, because the rapid technical progress at that time drove the loss of power of the aristocracy . The Junkers' ridiculous revolt against windmills was the ideal symbol for this.

Translations

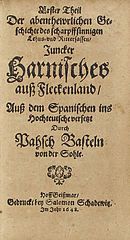

The first German translation was made in 1621 ( Don Kichote de la Mantzscha ) by Pahsch Basteln von der Solole (pseudonym of Joachim Caesar ). However, it did not appear until 1648 and only comprised the first 23 chapters. The translation by Ludwig Tieck published 1799–1801 is probably the best-known German translation to this day. The one made 50 years later by Ludwig Braunfels was long considered the most linguistic and knowledgeable. In 2008 the work was published in a two-volume German version, newly translated by Susanne Lange , which was highly praised by literary critics and whose linguistic dimension in German was compared with that of the original. In 2002, 100 well-known authors - organized by the Nobel Institute in Oslo - voted Don Quixote the “best book in the world”.

reception

The duality between the little fat man and the big thin man can be found again and again in modern literature since the novel Don Quixote . The main character Don Quixote, the "knight of the sad figure" and his servant Sancho Panza (translated "Sancho belly") form a comedian duo , which is formed from the classic configuration of tall, lean gentlemen and small, fat servants and numerous actor couples with the opportunity for great comedic achievements, such as in the film Pat & Patachon (1926), Fyodor Chaliapin / George Robey (1933), Nikolai Cherkassov / Juri Tolubejew (1957), Josef Meinrad / Roger Carel (1965), Jean Rochefort / Johnny Depp (2002), John Lithgow / Bob Hoskins (2000) and Christoph Maria Herbst / Johann Hillmann as well as in the musical Der Mann von La Mancha Peter O'Toole / James Coco (1972), Rex Harrison / Frank Finlay , Josef Meinrad / Fritz Muliar (1968), Karlheinz Hackl / Robert Meyer , Jacques Brel / Darío Moreno and Karl May's characters Dick Hammerdull / Pitt Holbers and Dicker Jemmy / Langer Davy .

The saying "de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme" (German: whose name I don't want to remember.) Became famous through the book. Like many other fragments of the book, it became a winged word in Spanish today.

Literary

The English writer Charlotte Lennox reversed the basic principle of Don Quixote on the young girl Arabella in her hit novel The Female Quixote in 1752 . Just as the Don sees himself as a chivalrous hero in the romance, the heroine, without knowledge of people and the world, misunderstands Arabella in her delusions as feminine love in her idealized romance. In this way, highwaymen and gardener boys become princes in disguise who want to kidnap their shifted perception of reality.

Even Christoph Martin Wieland adapted in his 1764 novel, The victory of nature over enthusiasm or the adventures of Don Silvio of Rosalva the Don Quixote story. Here the Quijotic situation is transferred to an obsessive fairy tale reader.

In the rather short preface to his novel Lucinde, Friedrich Schlegel refers to the preface to Cervantes' Don Quixote . Not only that the author (next to Boccaz and Petrarca ) is named as a model for prefaces (“And even the high Cervantes, also as an old man and in agony still friendly and full of tender wit, clad the colorful drama of the lively works the precious carpet of a preface, which is itself a beautiful romantic painting ”), but Schlegel, like the latter, reflects self-reflexively in his preface about the writing of prefaces. Schlegel also takes up the motif that the book is the son of the author's spirit, but uses it to introduce the theme of his own novel: erotic love and the poetry about it.

“But what should my spirit give to his son, who like him is so poor in poetry as he is rich in love? […] Not the royal eagle alone […] [,] the swan is also proud […]. He only thinks of snuggling up to Leda's lap without hurting him; and exhale everything that is mortal about him in chants. "

Franz Kafka takes up the subject in his prose piece The Truth About Sancho Panza (1917).

Graham Greene published his novel Monsignor Quixote in 1982, a pastiche whose main character, the Catholic priest Monsignore Quixote, is based on the character of Don Quixote.

Don Quixote was included in the ZEIT library of 100 books .

Plays

- Thomas d'Urfey : A Comical History of Don Quixote (1694)

- Tennessee Williams : Camino Real (1953) - Don Quixote and Sancho Panza are two of the main characters in this symbolist drama, along with other mythical and historical figures including Kilroy and Lord Byron

- Michail Bulgakow : Don Quixote - adaptation of Don Quixote by Cervantes for the stage, 1937–38; first published in 1962

- Christoph Busche : Don Quixote. Play for children from 3 years. World premiere on November 27, 2016 at Theater Kiel (Theater im Werftpark)

Music and musical theater

- Johann Philipp Förtsch : The erring knight Don Quixotte de la Mancia (premiere 1690 in Hamburg)

- Henry Purcell : Comical History of Don Quixote (1694/95)

- Joseph Bodin de Boismortier : Don Quixote chez la Duchesse

- Francesco Bartolomeo Conti : Don Chisciotte in Sierra Morena , tragic-comic opera (premiere 1719 in Vienna)

- Georg Philipp Telemann : Burlesque de Don Quixote , overture suite in G major for strings and basso continuo

- Josef Starzer : Don Quixote , Ballet v. Franz Hilverding in Vienna (1740), also in 1867 Jean-Georges Noverre

- Joseph Bodin de Boismortier : Don Quixote chez la Duchesse , ballet (Paris 1743).

- Georg Philipp Telemann: Don Quixote at the wedding of Comacho or also Don Quixote the Lion Knight (1761)

- Giovanni Paisiello : Don Chisciotte della Mancia , Opera buffa (WP 1769 in Naples)

- Antonio Salieri : Don Chisciotte alle nozze di Gamace , opera (premiere 1770/1771 in Vienna)

- Angelo Tarchi : Don Chisciotte , Ballet v. Paolo Franchi, Teatro all Scala, Milan (premiere December 1783)

- Noccolò Zingarelli : Don Chisciotte , Ballet v. Antoine Pitrot, La Scala, Milan (WP 1792)

- Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf : Don Quixote the Second (WP 1795)

- François-Charlemagne Lefebvre : Les Noces de Gamache , ballet by Louis Milon , Opera Paris (premiere 1801)

- Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy : The Wedding of Camacho , Opera (1825, premiered 1827 in Berlin)

- Saverio Mercadante : Don Chisciotte alle nozze di Gamaccio (premiered in Cadiz in 1830)

- Otto Zinck (Gioacchino Rossini, Étienne Mehul, Gaspare Spontini, Jean Schneitzhoeffer and others): Don Quixote at Camacho's Wedding , ballet by Louis Milon, August Bournonville in Copenhagen (premiere 1837)

- Antoine-Louis Clapisson : Don Quixotte et Sancho Opera (Premiere 1847)

- Léon Minkus : Don Quixote , Ballet v. Marius Petipa (premiered in Moscow in 1869; revised in St. Petersburg in 1871)

- Anton Rubinstein : Don Quixote , Humoresque for orchestra op.87, 1870

- Louis Roth , Max von Weinzierl : Don Quixote , comic opera in 3 acts. Text: Karl Grändorf (1875, UA Graz 1877)

- Wilhelm Kienzl : Don Quixote , Opera, op.50 (premiered in Berlin in 1897)

- Richard Strauss : Don Quixote , tone poem for large orchestra, op.35 (1897), as a ballet by John Neumeier (premiered in Hamburg 1979)

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold : Don Quixote. Six character pieces, piano cycle (premiered in 1908)

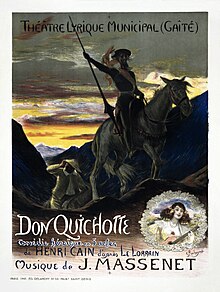

- Jules Massenet : Don Quichotte , opera (premiered in Monte Carlo in 1910, with Fyodor Chaliapin in the title role)

- Richard Heuberger : Don Quixote , operetta, text by Fritz Grünbaum , Heinz Reichert (UA Vienna 1910)

- Manuel de Falla : Retablo de Maese Pedro , opera (premiere 1923)

- Maurice Ravel : Don Quichotte à Dulcinée , songs (1932)

- Leo Spies : Don Quixote , Ballet v. Tatjana Gsovsky (1944, premiere 1949 in Berlin)

- Goffredo Petrassi : Le portrait de Don Quichotte Ballet by Aurelio Milloss (premiere 1947)

- Jacques Ibert : Le Chevalier Errant , Ballet v. Jerge Lifar, Paris (premiere 1950)

- Roberto Gerhard : Don Quixote , Ballet v. Ninette de Valois', (Premiere 1950)

- Mitch Leigh : Der Mann von La Mancha (The Man of La Mancha), Musical v. Dale Wasserman (book), Joe Darion (lyrics) (Premiere 1965 Off-Broadway, NY)

- Nicolas Nabokov : Ballet v. George Balanchine , New York (premiere 1965)

- Kenny Wheeler : Windmill Tilter , LP (1968)

- Hans Zender : Don Quijote de la Mancha , music theater (premiere 1993 in Stuttgart, director: Axel Manthey)

- Jan Koetsier : Don Quichottisen , for wind quintet, op.144 (1996)

- Mägo de Oz : La Leyenda de la Mancha (1998) and Molinos de Viento

- Herman Rechberger : Hola Miguel! , for two guitars (1998)

- Cristóbal Halffter : Don Quixote , opera (1996–99, WP 2000 in Madrid)

- Hespèrion XXI , Jordi Savall (conception and direction): Don Quijote de la Mancha. Romances y Músicas. Dramaturgical arrangement using contemporary music (2005)

- Rob Goorhuis : Don Quichote de la Mancha , for wind orchestra (2005)

- Thomas Scholz : Don Quixote , children's musical about the man from La Mancha; Children's musical (2005-2006), (premiered 2006 in Würzburg)

- Blackmore's Night The Village Lanterne (2006). (The song Windmills refers to the story of Don Quixote, but does not mention the name)

- The Casting Out : Quixotes last ride (2007)

- Bernhard Lang : Monadologie II - Der neue Don Quichotte , for large orchestra (premiered on August 26, 2008 under Fabio Luisi , Staatskapelle Dresden )

- Helmut Oehring : Quixote or The Porcelain Lance , Music Theater (2008)

- Theo Rupprecht : Don Quixote - Marche grotesque , arrangement for wind orchestra: Simon Felder

- Tobias Bungter: Don Quijote Theater with lots of music / World premiere June 14, 2014 / Stiftsruine / 64th Bad Hersfeld Festival

Filmography

The novel has been filmed several times since 1926, but with different focuses in the plot.

- 1926: Don Quijote , (Spanish-Danish co-production with Pat & Patachon )

- 1933: Don Quixote , director: Georg Wilhelm Pabst (British film recorded in three language versions (English, German and French) with Fyodor Chaliapin as Don Quixote)

- 1947: Don Quixote de la Mancha , directed by Rafael Gil (Spanish film with Rafael Rivelles as Don Quixote)

- 1955–1969: Don Quixote , director: Orson Welles (unfinished. Mexican-Italian film with Francisco Reiguera as Don Quixote, who died before filming was finished, completed in 1992 in Spain under the direction of Jesús Franco )

- 1957: Don Quixote , director: Grigori Kosinzew (Soviet film with Nikolai Cherkassov as Don Quixote)

- 1961: Don Kihot , directed by Vlado Kristl (an animated film from Yugoslavia that can be understood as a self-portrait of the director.)

- 1965: The story of Don Quixote von der Mancha (4-part TV version as part of the four-part adventure on ZDF , with Josef Meinrad as Don Quixote, Roger Carrel as Sancho Panza and Fernando Rey as Duke. This version is considered one of the most faithful film adaptations was released on DVD in 2006.)

- 1971: Don Kihot i Sanco Pansa , directed by Zdravko Sotra (Yugoslavian TV film)

- 1971: Don Kisot Sahte Sövalye (Turkish feature film, director: Semih Evin, Münir Özkul as Don Quixote and Sami Hazinses as Sancho Pansa)

- 1972: Man of La Mancha , directed by Arthur Hiller ( Musical version with Peter O'Toole as Don Quixote and Sophia Loren as Aldonza)

- 1973: The Adventures of Don Quixote (British television production with Rex Harrison as Don Quixote)

- 1973: Don Quixote ( ballet film with Robert Helpmann as Don Quixote and Rudolf Nurejew )

- 1978: Don Quixote de la Mancha (Spanish cartoon series)

- 1987: Dünki Schott (Swiss version by and with Franz Hohler )

- 1989: Tskhovreba Don Kichotissa da Santschossi (Soviet television series in Georgian with Kachi Kawsadze as Don Quixote)

- 1991: El Quijote de Miguel de Cervantes (Spanish TV series with Fernando Rey as Don Quixote)

- 1997: Don Quixote - Director: Csaba Bollók (Hungarian version)

- 2000: Don Quixote , directed by Peter Yates (American television film with John Lithgow as Don Quixote and Bob Hoskins as Sancho Panza)

- 2002: El Caballero Don Quijote , directed by Manuel Gutiérrez Aragón (Spanish film with Juan Luis Galiardo as Don Quixote, shown at the Venice Film Festival )

- 2005: Don Quixote or The Mishaps of an Angry Man (French film essay for television)

- 2006: Honor de Cavalleria , director: Albert Serra (Catalan feature film, realized with amateur actors, multiple awards, shown at several international film festivals (including: Cannes 2006, CineLatino 2007))

- 2008: Don Quixote - Never give up! , (German TV adaptation of Sat.1 with Christoph Maria Herbst as Don Quijote and Johann Hillmann )

- 2012: Don Quixote - Knights and Castles - Stories from Spain (documentary by Axel Loh)

- 2015: Don Quixote: The Ingenious Gentleman of La Mancha (American film with Carmen Argenziano as Don Quixote)

In addition to Orson Welles , Terry Gilliam also tried to film the material. The film The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was released in German cinemas in 2018 after a few adversities during the 17-year period in which it was made. Lost in La Mancha is a documentary about the film project.

Radio plays

- 1947: Don Quixote de la Mancha . Bayerischer Rundfunk , director: Fritz Benscher , actor not known.

- 1951: Don Quixote . Radio Saarbrücken , director: Wilm ten Haaf , actor not known.

- 1998: Don Quixote . Bayerischer Rundfunk , adaptation and direction: Walter Wippersberg , actors: Gerd Anthoff as narrator , Karl Lieffen as Don Quixote and Michael Habeck as Sancho Panza .

- 2004: Strange Adventures of Don Quixote . Südwestrundfunk , director: Günter Maurer , actors: Peter Rühring as narrator , Bernhard Baier as Don Quixote and Klaus Spürkel as Sancho Panza .

- 2009: The Adventures of Don Kid'schote . Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln , director: Frank-Erich Hübner , actors: Christoph Bäumer as Don Kid'schote and Harald Funke as Sancho .

- 2010: Don Quixote from the Mancha (6 parts). Deutschlandfunk , adaptation and direction: Klaus Buhlert , actors: Rufus Beck as Don Quijote , Thomas Thieme as Sancho Pansa and Anna Thalbach .

- 2014: Don Don Don Quixote - Attackéee . Deutschlandfunk in cooperation with the Ernst Busch Academy of Dramatic Arts in Berlin , directed by Hans Block , with Stefan Kolosko, Lisa Hrdina , Jan Breustedt, Matthias Mosbach, Max Meyer-Bretschneider, Alexander Höchst .

- 2019: Don Quixote of the Mancha . Südwestrundfunk , editing: Katrin Zipse , director: Kirstin Petri , actors: Tina Engel and Peter Fricke as narrators , Christian Brückner as Don Quijote and Daniel Zillmann as Sancho Panza .

miscellaneous

- The asteroid Don Quixote was named after him.

- A German-Turkish monthly humor magazine is called Don Quichotte .

- The romantic poet Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué was considered a crazy poet who sometimes got lost in his poetry and then could not distinguish between reality and fiction. That is why his contemporaries called him the “Brandenburg Don Quixote”.

- In 2005, Spain dedicated a 2 euro commemorative coin to the 400th "birthday" of Don Quixote .

- The writer Paul Auster draws parallels with Don Quixote in his City of Glass .

- In Bill Bo and his cronies , known for the film adaptation of the Augsburger Puppenkiste (1968) and playing at the time of the Thirty Years War , the character Don Josefo Spinoso von der Laweng is so inspired by the recently published novel Don Quixote that he is on every corner suspected the "silver knight".

- The Bavarian singer Fredl Fesl wrote a song of the same name about Don Quixote's horse Rosinante , which was released on his fourth album in 1981. In it he looks for reasons for her good-natured and obedient behavior towards her obviously mentally deprived master and comes to the conclusion that her grandfather was probably a "German Trakehner ".

- In Asterix band Asterix in Spain has Don Quixote a brief appearance in which he the saying "Windmills? To attack! ”.

- In the German comic magazine Mosaik , Don Quijote and Sancho Panza accompanied the adventures of the main characters Abrafaxe in issues 1/1981 to 1/1982 .

- A free comic adaptation comes from Flix , which is set in Germany today and appeared as a sequel in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in 2012 .

- In the Cuban city of Holguín there is a monument depicting Don Quixote fighting a windmill.

- A museum in the Mexican city of Guanajuato only exhibits paintings and works of art related to the novel. In addition, the very popular theater festival Cervantino has been held in Guanajuato every year since 1972 , as part of which cultural events related to Don Quixote are held.

- The series Back to the Past dedicated an episode to him (season 2, episode 10) in which a musical is played about him.

- In the manga One Piece, there is a character named Don Quixote De Flamingo, alluding to Don Quixote. His younger brother is called Rocinante in the manga, based on Don Quixote's horse.

- In the series The Newsroom (2012–2014) by Aaron Sorkin , references are made to the literature and character of Don Quixote in the context of a fictional news program that puts honest and investigative journalism before sensationalism .

literature

German editions (selection)

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Kichote de la Mantzscha , that is: Juncker Harnisch out of stains / Out of Hispanic language translated into German […] By Pahsch handicrafts from the sole [= Joachim Caesar ]. Götze, Frankfurt a. M. 1648. Further edition: Ilssner, Frankfurt a. M. 1669, digitized .

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: life and deeds of the astute noble Don Quixote of la Mancha. Translated by Ludwig Tieck . 4 vols. Berlin 1799–1801.

Current issues:- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote de la Mancha. First part: The astute noble Lord Don Quixote de la Mancha; Second part: The astute knight Don Quixote de la Mancha . Edited and newly translated by Anton M. Rothbauer Stuttgart 1964, based on 'El ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha, new critical edition in ten volumes, obtained by F. Rodríguez Marín, Madrid 1947–1949.

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: The ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote von der Mancha , 2 volumes, Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1953, Dieterich collection, volumes 150 and 151, with comments by Werner Bahner , an essay by Karl Vossler and the text "The Spanish Route in the life's work of Cervantes "by Werner Krauss .

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Life and Deeds of the Discerning Noble Don Quixote of La Mancha. With numerous Note library of world literature. Structure , Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-351-02992-6

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: life and deeds of the astute noble Don Quixote of la Mancha . Translated by Ludwig Tieck . Afterword by Heinrich Heine . Diogenes, Zurich 1987, ISBN 3-257-21496-0 .

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote. Patmos , Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-491-96083-5 .

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: The astute knight Don Quixote of the Mancha. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1955 (translation by Konrad Thorer using an anonymous edition from 1837).

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: The ingenious Junker Don Quixote of the Mancha. dtv, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-12351-6 (translation by Ludwig Braunfels ); Artemis and Winkler, Düsseldorf 2000, ISBN 3-538-06531-4

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote from the Mancha. Carl Hanser Verlag , Munich 2008 ISBN 978-3-446-23076-7 (new translation Susanne Lange, 2 volumes)

- as paperback: Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote von der Mancha. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag , Munich 2011 ISBN 978-3-423-59010-5

- Susanne Lange , Interview: Cervantes' language as El Dorado for the translator , an interview with newspanishbooks.de about her new translation. ReLÜ , Review Journal , No. 15, 2014

- as paperback: Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote von der Mancha. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag , Munich 2011 ISBN 978-3-423-59010-5

- Flix: Don Quixote. Carlsen, Hamburg 2012 ISBN 978-3-551-78375-2 (adaptation as graphic novel).

Secondary literature

- Azorín : La ruta de Don Quixote. 1905.

- Michael Brink : Don Quixote - Image and Reality. Lambert Schneider, Berlin 1942; 2nd expanded edition Lambert Schneider, Heidelberg 1946; Reissue. Autonomie und Chaos publishing house, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-923211-17-3 .

- Gisela Burkamp (ed.): Traces of Don Quixote. A collection of paintings, drawings and graphics, sculpture, books and bookplates from the 18th century to the present day. Kerber, Bielefeld 2003, ISBN 3-936646-21-X .

- Roberto González Echevarría (Ed.): Cervantes' Don Quixote. A casebook. Oxford University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 0-19-516937-9 (collection of articles).

- Johannes Hartau: Don Quixote in art. Changes in a symbolic figure. Mann, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-7861-1449-8 .

- Hendrik Heisterberg: Don Quixote in the invisible cinema. An analysis of failed film adaptations of Cervantes' "Don Quixote de la Mancha". Telos, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-933060-23-5 .

- Stephan Leopold: Conquest parodies - sheep, puppets, islands and the other in "Don Quixote". In: Iberoromania 61 (2005), pp. 46-66.

- Louis A. Murillo: A critical introduction to Don Quixote. Lang, New York 1990, ISBN 0-8204-0516-7 .

- Vladimir Nabokov : The Art of Reading. Cervantes' "Don Quixote". S. Fischer, Frankfurt a. M. 1985, ISBN 3-10-051504-8 .

- Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer : La ética del Quijote. Función de las novelas intercaladas. Gredos, Madrid 1999, ISBN 978-8-424919-89-4 .

- David Quint: Cervantes's novel of modern times. A new reading of Don Quixote. Princeton University Press, Princeton 2003, ISBN 0-691-11433-1 .

- Edward C. Riley: Don Quixote. Allen & Unwin, London 1986, ISBN 0-04-800009-4 (Introduction).

- Isabel Ruiz de Elvira Serra (editor): Don Quixote. Spend in four hundred years. Museum of Arts and Crafts, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 84-7483-775-8 .

- Javier Salazar Rincón: El mundo social del Quixote. Gredos, Madrid 1986, ISBN 84-249-1060-5 .

- Javier Salazar Rincón: El escritor y su entorno. Cervantes y la corte de Valladolid en 1605. Junta de Castilla y León, Valladolid 2006, ISBN 84-9718-375-4 .

- Christoph Strosetzki: Miguel de Cervantes. Epoch - work - effect. Workbooks on the history of literature. Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-35077-1 .

- Christoph Strosetzki: Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote. Explicit and implicit discourses in “Don Quixote”. Study series Romania. Vol. 22. Schmidt, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-503-07939-4 (collection of articles, content ).

- Bernhard HF Taureck : Don Quixote as a lived metaphor. Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-7705-4721-0 .

- Miguel de Unamuno : Vida de don Quixote y Sancho, según Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, explicada y comentada. Alianza Editorial, Madrid 1905, 2005, ISBN 84-206-3614-2 .

- Jürgen Wertheimer : The Cervantes Project. Konkursbuch Verlag, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-88769-348-5 .

media

- Don Quixote de la Mancha . Radio play . Radio play adaptation: Walter Andreas Schwarz . Director: Ulrich Lauterbach . Speakers among others: Walter Richter , Willy Birgel . Date of recording 1962. 6 CD. Dhv, 2003 ISBN 3-89940-144-1 .

- Adventure classics - treasure island, sea wolf, leather socks ... 2 CD. BSC Music, prudence 398.6619.2 (with music from the ZDF four-part series).

- Original Broadway cast of the musical version The Man of La Mancha CD 1965, (new CD from 2002 with Brian Stokes Mitchell as Don Quijote, Marie Elizabeth Mastrantonio as Aldonza and Ernie Sabella as Sancho Pansa via download from the web; German version (Vienna) with Josef Meinrad , as well as a recording with Plácido Domingo as Don Quixote and Julia Migenes as Aldonza.)

- Miguel de Cervantes: Don Quixote de la Mancha. Romances y Músicas, Montserrat Figueras, Hespèrion XXI, La capella reial de Catalunya, Jordi Savall. Translated in 7 languages. 2 CDs with music of the era and thematically related to the novel.

Web links

- Scan of the first edition of the first part.

- Scan of the unofficial sequel and original text.

- Scan of the second part of Cervantes, first edition.

- Don Quijote at Zeno.org ., Based on the translation by Ludwig Tieck in the edition: Berlin, Rütten & Loening, 1966.

- The ingenious Junker Don Quixote von der Mancha - First book in the Gutenberg-DE project in the translation by Ludwig Braunfels

- The ingenious Junker Don Quixote von der Mancha - Second book in the Gutenberg-DE project in the translation by Ludwig Braunfels

- Digitized full text from Don Quijote Duke University, bilingual Spanish-German edition (Braunfels translation), accessed on December 4, 2019.

- 28 illustrations for Don Quixote by Stefan Mart (1933).

- Gustave Doré’s illustrations for Don Quixote Part 1 (English).

- Gustave Doré’s illustrations for Don Quixote Part 2 (English).

- Illustrations by Gustave Doré (with thumbnails , scroll to Don Quixote).

- Summary and Analysis Book I In: GradeSaver.com. (English). Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- Summary and Analysis Book II In: GradeSaver.com (English). Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- Concordances based on the original Spanish text

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernhard König: The erring knight and his stable master. Two comments on Tieck's translation of Don Quixote. Romance Yearbook, Volume 12, Pages 343–351, December 31, 1961, pp. 343–351 ( online preview )

- ↑ Don Quixote, Hamburg 1961, afterword by Kai E. Kösling.

- ↑ Eberhard Geisler : What remains of the cultural openness , in: taz , April 23, 2016, p. 24

- ^ Villanueva de los Infantes (Spanish).

- ↑ Uwe Neumahr: Miguel de Cervantes. A wild life. CHBeck, Munich 2015, limited preview in the Google book search

- ↑ Erich Auerbach: Mimesis. (1946) 10th edition, Tübingen, Basel 2001, p. 331.

- ^ A. Gibson: Don Quixote . In: Reading Narrative Discourse . Palgrave Macmillan, London 1990, doi : 10.1007 / 978-1-349-20545-5_2 .

- Jump up ↑ Erikson's dog: Don Quixote - Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1605). In: DISCOURSE. December 21, 2016, accessed March 4, 2017 .

- ↑ Chritian Linder: Knight of the sad figure. Deutschlandfunk Kultur , October 11, 2005, accessed on October 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Literature choice: "Don Quixote" is the best book in the world. In: Spiegel Online. May 7, 2002, accessed October 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Pierre Temkine: Waiting for Godot. The absurd and the story. Edited by Denis Thouard and Tim Trzaskalik. Translated from the French by Tim Trzaskalik. Matthes & Seitz Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-88221-714-8 .

- ↑ Don Quixote - Theater Kiel . In: @TheaterKiel . ( theater-kiel.de [accessed on June 5, 2018]).

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk

- ↑ SWR 2

- ↑ Don Quixote Chapter - MosaPedia. Retrieved October 20, 2018 .

- ↑ FAZ.net May 4, 2012 , accessed on March 9, 2019