The monastery of love

The Kloster der Minne is a Minnerede or Minneallegorie from the 2nd quarter of the 14th century. The poem consists of up to 1890 rhyming verses and was probably written between 1330 and 1350 in southern Germany. The author is unknown.

The Monastery of Minne is about a hiker who is shown the way to a monastery by a mounted messenger. In the monastery, the head of which is supposed to be Mrs. Minne herself, he meets an acquaintance who shows him the building and with whom he watches a tournament before he leaves the monastery again. Despite repeated inquiries, he did not get to know love personally, as it is only visible in its effect on the monastery residents.

Due to the uncertain chronology and the anonymity of the author, the Monastery of Minne has repeatedly come into the focus of literary studies since the 19th century, for which it was primarily under the aspect of a presumed content-related relationship with the rules of the order until the late 20th century of Ettal Abbey was of interest. In terms of content, the peculiarity of the work compared to other narrative Minne speeches and Minneallegories is that it dispenses with personifications, so Frau Minne does not appear as a woman, for example.

Lore

Cod. Donaueschingen 104 ("Liedersaal manuscript")

The oldest known manuscript of the Monastery of Minne is contained in Cod. Donaueschingen 104. The code was created around 1433 and is written in the Alemannic dialect . The clerk probably came from Constance. The manuscript was originally 269 sheets thick. The Monastery of Minne is 1890 verses long. Of all three surviving manuscripts, it is the oldest and most reliable version, which is also the best preserved. The Minnerede has no heading in the Donaueschingen manuscript. Cod. Donaueschingen 104 is now kept in the Baden State Library.

Joseph von Laßberg published the Donaueschingen manuscript from 1820 to 1825 under the title Lieder Saal. This is a collection of old German poems from unprinted sources . Laßberg gave the Minnerede, then without a title, the title The Monastery of Minne . After Laßberg, who considered the Monastery of Minne to be the most beautiful work in his collection, Cod. Donaueschingen 104 is also referred to as the “Liedersaal manuscript”.

Codex Dresden M 68

The Codex Dresden M 68 comes from Augsburg and was written in 1447 by Peter Grienninger in East Swabian dialect . The manuscript has a total of 79 pages and contains 35 smaller poetic texts, such as mars , prayers, love letters and miner speeches , including the ministry of Johann von Konstanz . The Monastery of Minne includes verses in this manuscript in 1866. The Codex Dresden M 68 is the most deficient of the surviving manuscripts. It contains numerous individual verses, some of which even impair the sense, and has redundant plus verses, while at the same time rhyming pairs of the other manuscripts are missing. Peter Grienninger was also not always sure of the spelling: Grienninger gave the Minnerede the title De monte feneris agitur hit , which was corrected to De monte feneris agitur hic (translator: This is about the Venusberg ). The manuscript is now kept in the Saxon State and University Library in Dresden .

Cod. Pal. germ. 313

The latest surviving manuscript from the Minne Monastery is kept in the Heidelberg University Library. The Cod. Pal. germ. 313 is 498 pages long and dates from 1478. It was written in the North Alemannic- South Franconian dialect, which is why the Upper Rhine area is believed to be the origin of the writer today. The Cod. Pal. germ. 313 contains besides the Monastery of Minne , which has been handed down on 63 pages and in 1884 verses, 55 other minnered speeches from Heinrich der Teichner (knight or servant) , Meister Altswert ( the old sword , the smock ) and Fröschel von Leidnitz (Overheard love conversation) . The Minnerede The Monastery of Minne is surrounded by Johanns von Konstanz Minnelehre and Hermanns von Sachsenheim Spiegel .

Handwriting ratio

None of the three paper manuscripts handed down to the Monastery of Minne represents the original archetype. On the basis of the known manuscripts, two branches of the Monastery of Minne can be reconstructed. The Codex Donaueschingen forms one of the two branches, since it lacks four verses that both the Codex Dresden M 68 and the Cod. Pal. germ. 313 included. Because both of the younger manuscripts are missing a verse that the Codex Donaueschingen has, there must be a common template for these manuscripts that refers to the archetype. The Codex Dresden M 68 cannot match the Cod. Pal. germ. 313 have served as a template because the Cod. pal. germ. 313 together with the Donaueschingen manuscript contains verses which are missing in Codex Dresden M 68. The age of the manuscripts also includes a copy of Codex Dresden M 68 from Cod. Pal. germ. 313 from.

content

walk in the woods

The first-person narrator goes for a walk in May that takes him into a forest. He admires the flowers, the green treetops and the song of the nightingale and lark. Soon he sees a rider among the trees. He hides from her until her horse is close to his hiding place, and only then does he reveal himself. He grabs the horse by the bridle and prevents the lady from riding on. Before he lets her go, he wants to know what the aim and purpose of her ride alone in the forest is. The woman explains to him that she is traveling as a messenger of werdi Minne , who as the noble queen has power over all countries on earth. The first-person narrator is not yet satisfied with the information and asks to know what the intention of her trip is. The rider explains that she is looking for women, knights and servants who should come to love. After asking again, the rider reveals further details: A (building) master would have created a unique, huge monastery in which love would live. Anyone who goes to the monastery has a wonderful life, and people from all walks of life go there: kings, dukes, counts, maidservants, knights and servants. All residents would have to adhere to a monastery rule according to which they should be subject to love, that is, let their lives be determined by (courtly) love. They are allowed to sing, read, make music and dance. Numerous games such as bowling, chess, mill or dice for money would be allowed, the monastery residents were allowed to fence, wrestle, hunt and of course ride tournaments. Anyone who did not know how to behave in the spirit of love would be expelled from the monastery or severely punished in some other way.

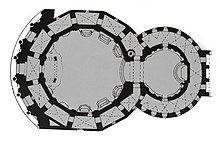

The shape and type of the monastery are unique: it is circular and unimaginably large. ez was kain horse never so snel / that it in ainem gantzen jar / the closter umbe lüffe even. The monastery has twelve doors that stand for one month each. Theoretically, the residents of the monastery have the opportunity to live constantly in their favorite month. The first-person narrator is fascinated by this world and desires to see the Monastery of Minne with his own eyes. The rider describes the way to the monastery, which the narrator - choosing the right path at a fork in the road - will enter via the May gate. The narrator is satisfied with the answers and lets the rider move on. After a short time he himself meets the Monastery of Minne.

Arrival at the monastery

When he stands in front of the walls of the area, a crowd of men and women pulls out of the monastery gate into the open and gathers for a dance. They seem to be lovers who, after the dance, sit down in pairs in the shade of the trees in front of the monastery gate. The first-person narrator notices (marriage) rings on numerous fingers and feels miserable. The couples also include numerous acquaintances from earlier days who, however, do not recognize the first-person narrator. Suddenly a bell is struck. A Junker announces the arrival of 500 knights and servants who want to hold a tournament with the monastery inmates . As a prize in the spear fight , the best knight is promised the coat of arms of a lion with a gold chain. The best servant should receive the coat of arms of a leopard with a silver chain. The men go back to the monastery to prepare for the tournament.

Tour through the monastery

The narrator discovers a good friend among the women who have stayed behind. She tells him that she has been living in the monastery for ten years and, accompanied by some other women, shows him the monastery: The large monastery courtyard is surrounded by a main building, into which a door leads from each of the four walls. The building has balconies and bay windows and is made of different colored, partially openwork marble. The walls shine like mirrors, so that the whole building appears incomparably beautiful to the first-person narrator. However, his companion points out that there are many of these buildings in the monastery.

Since the tournament is about to start, the other women say goodbye to the first-person narrator. The acquaintance stays with him and discusses the nature of the order. Minne rules over all monastery residents , who, however, are presided over by an abbot and an abbess as well as a prior and a prioress. Whoever does not obey the rule of the monastery will be punished. The nature of the punishments is shown on a tour of the monastery prison: a chatterbox is tied up with a collar . He asks the first-person narrator for bread because he is dying of hunger and begs the first-person narrator to ask the abbot for mercy because he has been trapped for insulting a woman for three years. The companion warns the first-person narrator that he was making himself unpopular if he spoke to the abbot on this matter. After the narrator has promised her not to intercede for the prisoners, the companion leads him to a braggart who is tied to a foot block on old straw . Originally he was a noble servant who, however, boasted about his love affairs. Mockers, envious people, fickle-minded people and cowards are also in the prison of the monastery, but the first-person narrator decides to return to the other women with his companion and watch the tournament.

The tournament

The first-person narrator and his friends see the monks of the monastery in knight armor. Shortly afterwards the guests of the monastery appear in the palace courtyard and the tournament begins. In the course of this, the first-person narrator pretends to be impartial, but at the same time rarely knows who is one of the guests and who is among the inmates of the monastery. At the end of the tournament, the prior is awarded as the best knight, and the porter of the monastery as the best servant. Both are attacked again by guests after receiving their awards. The prior can defend himself successfully, but the porter is seriously injured and has to be carried off the field. When the first-person narrator points out to his horrified companion that tournaments have to be brutal in order to win the hearts of women, his acquaintance teaches him: tournaments are primarily only of use to the knight or servant who can improve his fighting skills in the game and himself so that I can make a name. There would certainly be a few men who only fight for the sake of women, but they would have misunderstood the real purpose of the tournament. The first-person narrator and his acquaintances talk about the basic structure of the monastery, in which there is no room for traitors, robbers and usurers. But if you want to go / and keep this rule, / you want to serve in joyful old ways / and still serve there. When the narrator finally wishes to see the love in person, he justifies this with reports that include the love her arrow would wound her body and heart and people would torment themselves as a result. His acquaintance explains to him that love itself is invisible and can only be recognized in all its effects between the men and women of the monastery, which the narrator does not want to believe. When the friend feels mocked by him, he apologizes to her and thanks her for her help. She implies that they could become a couple if she knew him longer. Since the guests defeated in the tournament want to come back in 12 days, the friend invites the first-person narrator back to the monastery in 12 days. During this time, the still undecided man could decide whether he wanted to spend the rest of his life in the monastery or not.

farewell

The acquaintance and one of her friends want to take the first-person narrator to the monastery gate, but briefly return to the acquaintance's room, which is richly adorned and decorated. The first-person narrator feels uncomfortable in the small room. When the acquaintance shows him her big bed, he would like to throw himself on the bed (with her), but doesn't dare. The companion, who guesses his thoughts, laughs at him. Together they drink St. Johannis Minne, then the narrator leaves both women in the room and hurries out of the monastery. He gets back into the forest, where the song of the birds and the flowers seem to him void in contrast to the colorful monastery bustle. He longs to return to the monastery and knows that I've got to live so long / I want to go to the closter / and keep the rule / and the old closter .

Genre, literary templates and style

genus

The monastery of Minne belongs to the literary genre of the so-called Minnereden, which was mainly widespread in the late Middle Ages, and can also be referred to as Minne allegory .

Minner speech

The text is a Minnerede because it treats the topic of worldly love (Middle High German Minne ) in an instructive or instructive way. This results from the plot: questions from the narrator are answered by his companion, counter-questions from the narrator follow. The course of the plot follows the course of the didactic conversation between the first-person narrator and his lady as well as between the first-person narrator and the Minnebotin in the forest at the beginning of the plot. However, didactic sections alternate with narrative and descriptive passages (for example during the tournament).

Minneallegory

The Monastery of Minne can be described as a Minneallegorie with restrictions . “The actual allegory is missing, not only because none of the ... otherwise popular personifications such as honor, shame, place, dignity, confidence, etc. The like. But also the love itself does not appear personally, the much mentioned one. ”The expectations of the reader in this regard are deliberately deceived because the love is apparently described as a person in the narrator's conversation with the messenger, so she is the mistress of the messenger and has power over the alli lant ; she is a noble queen . The narrator consequently asks himself when he arrives at the monastery and sees the residents dancing, whether the love of love is perhaps one of the dancing women. He explains to his companion that he wants to see love, and she leads him to the people of the monastery who are together in harmony. The narrator nevertheless expects to see love as a person.

- I said: "Deari fro, say

- if nü does love come? "

- si said: "hasty nit senses,

- ald how do you feel?

- wiltü nit minne six

- here on this theras,

- so ask for minn nit furbaß! "

Ms. Minne is only visible in her effects on people, but not physically present. Glier describes the love conception of the text as a "rather indirect allegory". Richter refers to "an older conception" that defines love as a ghostly, invisible being, as is the case, for example, in the didactic poem Die Winsbekin , in which the daughter asks the mother: nu tell me whether love is alive / and here bî uns ûf erde sî / od ob us in the air swebe , whereupon the mother replies, referring to Ovid , that si vert unsictic as a ghost .

The building of the monastery can be interpreted allegorically. It has twelve gates, each of which stands for a month, creating twelve different climatic zones in the monastery interior and vestibule. It is circular and also so large that the number of residents is infinite and a horse could not walk around the monastery in a year. Wolfgang Achnitz used this information for the following calculation:

“If you take this information literally and generously assume that a horse trying to hurry covers about 60 kilometers a day, depending on the gait, this results in a circumference of the facility of almost 22,000 kilometers, from which a diameter of around 7,000 kilometers can be calculated . This corresponds almost to the distance from the northern polar circle to the equator or that of Gibraltar in the west to India in the east, thus the area of the entire known orbis terrarum of the 14th century. "

Thus, the monastery should not be understood as a real building, but should only relate allegorically to the domain of love, which is also mentioned in the text itself: she has power over the alli lant and with regard to the simultaneously existing seasons at all times. The size of the monastery and the climatic peculiarities are mentioned in the work at the beginning, "but not developed to full clarity" and play no role in the further course of the plot. For Anke Roeder, the Monastery of Minne can therefore be described as "a Minner speech rather than an allegory".

Literary templates and further work

The motif of the allegorical monastery can already be found in Latin poetry of the Middle Ages, for example in Hugo de Folieto 's De claustro animae from 1160. In the third and fourth books of his treatise, the four pages of the monastery of the heavenly Jerusalem represent the four cardinal virtues.

Andreas Capellanus ' (Andreae Capellani) treatise De amore libri tres was written around 1185. In the middle of the (dead) world there is a palatium amoris . It is a square palace with four gates. In the east is the god Amor, who sends out his arrows of love. In the south are the women who always keep their palace gates open. They are open to love because they are hit directly by Cupid's arrows. In the west, prostitutes prowl in front of their palace gates, who turn no one away, but are not hit by Cupid's arrow. In the north the gates are locked. The women rejected love during their lifetime and were therefore condemned by Cupid.

In its design, the Monastery of Minne draws on motifs from Latin poetry, but also links them with stories about the place where the goddess of love lived, as De monte feneris agitur hic shows with the reference to the Venusberg fabric. This was processed in the form of the “Minnegrotte”, for example in Gottfried's Tristan from Strasbourg .

The Monastery of Minne may have influenced the work The Secular Little Monastery, written in 1472 . However, direct relationships cannot be proven. The Minneallegories ascribed to Meister Altswert (especially Der Tugenden Schatz ) also show parallels to the Monastery of Minne . "But otherwise the poem - in contrast to the allegorical teaching of Hadamar von Laber at the same time - hardly had any recognizable effect."

stylistics

The Monastery of Minne is a “poem written in elaborate verse”. It is written in paired rhymes , the verse is flowing. The narrative is kept simple, so large parts of the text consist of the narrator's conversation with the messenger of love and his companion in the monastery. His questions are followed by explanations from the companion, or the companion asks questions about the extent to which the narrator likes what he sees. For this, formulaic expressions are used, the companion's questions, for example, are regularly introduced with dear socially, nü tell me ... or dear sociable, as you like . This structure was seen as a "convenient means of dividing chapters and structuring, especially in larger descriptive poems", but was also criticized: "There is little animation from such a sham dialogue."

The author uses rhetorical stylistic devices such as word clusters and parallelisms , but the weakness of the text is the uniformity of the expression. Vocabulary of praise, which is used, for example, to describe the monastery or the chamber of the companion, is essentially limited to the words beautiful , precious and rich , which are used repeatedly. The tournament description is based on the combination of the words run and stab . Nevertheless, for Laßberg, for example , the Monastery of Minne was considered the most beautiful poem of his Liedersaal, which can be explained, among other things, by the clarity of the story: not just to vary topoi again ”. Schaus also emphasizes the naturalness of the descriptions and Glier emphasizes the "unusually easy and variedly designed" conversations.

Author's question and chronological order

Since neither the author nor the time of origin do not emerge from the work itself, the Minner Speech Das Kloster der Minne offers space for interpretation and speculation. Since the “rediscovery” of the work in the course of its publication by Joseph von Laßberg, attempts have been made again and again to determine the time of origin and the author.

Lion covenant

In 1895 Georg Richter placed the work in the second half of the 14th century. He saw this proven above all in the tournament prizes, which included the coat of arms of a lion with a gold chain for the best knight and a leopard with a silver chain for the best servant. Richter saw a parallel to the Lion League , which was founded in 1379, as a given. Each knight had to wear a gold and each servant a silver lion as a badge, according to a chronicle of the Strasbourg-born Jakob Twinger von Königshofen , it is said to have been either a lion or a panther made of gold or silver. A lion on a chain would also have been viewed in research as a badge of the lion society. Therefore Richter saw the time of origin of the Minnerede after 1379 as a given, a view that is no longer shared in today's research. On the one hand, the secular knightly society of the Order of Lions has left no political traces in the religious knightly order of the Monastery of Minne , on the other hand, the lion and panther are common medieval heraldic animals, so that a mere similarity of the society badges cannot indicate a dependency.

Complaint for a noble duchess

In Laßberg's Liedersaal , the monastery of Minne is immediately followed by the anonymous Minner speech complaining about a noble duchess . Here the poet meets a group of knights and friends who have witnessed the death of a Duchess of Carinthia and Tyrol , née. Lament the Countess of Savoy . You remember the time when the esteemed woman was still alive and describe, among other things, a tournament as it used to be at her court. As early as the 19th century, Richter and Emil Schaus saw a connection between the two tournaments. While Richter only recognized one dependency, Schaus went so far as to assume the same author for both works. He saw this not only in the linguistic agreement of the tournament descriptions but also in the otherwise unused word walke (n) (meaning "balcony"), which can be found in both Minnereden. Ehrismann also sees an author identity "proven by various literal echoes", while Niewöhner excludes author equality through linguistic deviations and "considerable differences in comprehension technique and style". Glier also sees linguistic differences, but does not want to rule out the possibility of author equality: “The linguistic differences are not so important. The 'Lament for the Dead' is stylistically, metrically and rhyming more awkward than the 'Monastery of Minne', but it cannot be ruled out that both are works by a poet whose writing skills have increased. ”In addition, like Schaus, she sees that“ the descriptions of the tournaments in both poems are so similar that one must suspect some dependencies behind them. germ. 313 are included.

Laßberg suspects the deceased Countess to be Heinrich of Carinthia's third wife , Beatrice of Savoy . Since the lawsuit reacts to the lady's death and, according to linguistic evidence, was built earlier than the Monastery of Minne , the Monastery of Minne was built after 1331.

The author's social background could also be determined more precisely if the authors were identical. In the lawsuit for a noble duchess , the author calls himself, as in the Monastery of Minne, “junker” and travels as a wandering singer of knightly class. He can read and write and is a Swabian , “a traveler who tries to comfort the Duke of Carinthia for good wages with an allegory of the taste of the times [...] and who wants to earn his thanks to Ludwig the Bavarian at another time through a fantastic glorification of the imperial favorite creation. "

Ettal Abbey

The search for a connection between the Monastery of Minne and the Monastery of Ettal , which, as Wolfgang Achnitz shows, proves to be fruitless, remains very persistent in researching the time of origin . Here - due to the founding of Ettal in 1330 - the time of origin of the Minne Monastery would be in the 1330s or up to a maximum of 1350 shortly after the construction of the monastery.

The Ettal Rule

The Ettal Abbey was founded in 1330 and received the Ettal Rule 1332, which was written in German and laid down everyday life in the monastery. In addition to priests and monks, 13 knights should also live in the monastery with their wives. If a knight died, his wife was allowed to stay in the monastery until her death. The knights and their wives were allowed to hunt and gamble, but not for money. Dancing and excessive alcohol consumption were also prohibited, children were not allowed to be brought into the monastery; Children born in the monastery had to leave Ettal after they were three years old. The clothes were supposed to be simple and were determined by color. Knights were not allowed to have horses of their own, but could borrow horses from the monastery.

The Monastery of Minne also has a “monastery rule” that runs through the text like a red thread. Again and again it is emphasized that a resident of dec closters should follow the rules. This consists in being subject to love and not acting contrary to it. At the same time, only the one who was actually hit by dü Minn with ir strale can stay in the monastery . The first-person narrator sums it up correctly: he is absolutely wrong / he sy ritter or servant / who decides not to / who doesn’t like to heart. Only when action is shaped by love in the broadest sense is it good action. At the same time, unwritten rules can be seen in everyday life in the monastery. The monastery residents are allowed to play for valuables, they roll dice, play the mill, bowling and dancing. It is up to the residents what clothes they wear and while the monastery rule explicitly states that hats must be simple, the first thing the narrator notices about the Minnebotin is her hat, which is decorated with an ostrich feather and other decorations. Horses are so abundant in the monastery that they can even be loaned to visitors for the tournament. Richter therefore points out that "Ettal's rule [...] in some points [says] the exact opposite of that of the Minnekloster." Even more than 50 years later, one does not commit: "The constitution could have been the template Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian gave it to the Ettal monastery, which he founded, in 1332, but the poet certainly did not intend a realistic depiction. "

The monastery as a knight's convent

In addition to a monks' convent under the direction of the abbot, the Ettal monastery also had a knight's convent, which was led by a master, and a women's convent, which was subordinate to the master. At that time, Ettal Abbey was more like a knight's monastery with monastic shapes, which also existed in the Monastery of Minne . Here it says: daz is ain raine / sociable brotherhood. / I don’t have any knighthood / in dekainem closter I want to be. Research has also seen this connection: "Ettal offered him [the author] the idea of a knightly monastery, he roughly worked it out", for example by making the master and the master an abbot and an abbess and a prior and a prioress . Since the author did not intend to give a realistic description of the Ettal monastery, the joys of such a life were emphasized and the monastery residents were allowed to dance, play and fight in tournaments.

The monastery building

Ettal Abbey was originally a twelve-sided Gothic central building , which was only extended by numerous additions over the centuries. According to Schaus, the unusual shape might have awakened the author's idea of a monthly belt, which he transferred to the Monastery of Minne . The Minnerede monastery building is round, but has twelve gates that stand for one month each and create twelve different climatic zones in the monastery interior and vestibule.

The monastery of love - a wrong world

Whether in comparison with other Minne speeches or with details of the rules of the order and the construction of the Ettal Monastery - in the search for a coherent overall concept of the Monastery of Minne , inconsistencies and breaks quickly come to light that prevent a final assessment.

But as soon as you stop taking the text seriously, it turns out to be a rare gem of parodic literature: In the reverse of the classic themes and motifs from heroic epics and Minne lyricism, a hero appears in the Monastery of Minne who believes he is doing everything right and at the same time stumbles from one faux pas to another - a Don Quixote avant la lettre.

Current state of research

In 2006, Wolfgang Achnitz went into the previous research on the Monastery of Minne in the area of temporal classification through the connections between the Monastery of Minne and the Monastery of Ettal or the Lion League and summarized the following:

“In any case, the result should be that dependencies, which in any case would only be of importance for an exact dating of the Minne narrative, cannot be proven, since parallels can be found in the statutes of the great orders of knights ( Johanniter , Templer , German gentlemen ) as well as in the literature of the previous period. The same applies to the tournament awards, which in the 14th century were often used in a similar form at tournaments and festivals of knight societies. "

Editions

- Joseph von Laßberg (ed.): Lieder Saal. This is a collection of old German poems from unprinted sources . Volume 2. o.A. 1822, pp. 209-264. (Reprinted by Scheitlin and Zollikofer, St. Gallen 1846, reprinted Darmstadt 1968)

- Maria Schierling: "The Monastery of Minne". Edition and investigation . Kümmerle, Göppingen 1980, ISBN 3-87452-356-X .

- Paula Hefti (Ed.): The Codex Dresden M 68. Edition of a late medieval composite manuscript . Francke, Bern and Munich 1980, ISBN 3-7720-1326-0 .

literature

- Emil Schaus: The Monastery of Minne . In: ZfdA 38, 1894, pp. 361-368.

- Georg Richter: Contributions to the interpretation and text reconstruction of the Middle High German poem "Kloster der Minne" . Bernhard Paul, Berlin 1895.

- Kurt Matthaei: The "Secular Monastery" and the German Minne Allegory . Univ. Diss., Marburg 1907.

- Gustav Ehrismann : History of German literature up to the end of the Middle Ages . Volume 2: Middle High German Literature. Beck, Munich 1935, pp. 504-506.

- Heinrich Niewöhner: The monastery of love . In: Wolfgang Stammler, Karl Langosch (Ed.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Volume 3. De Gruyter, Berlin 1943, Sp. 395-403.

- Heinrich Niewöhner: Minnered speeches and allegories. In: Wolfgang Stammler, Karl Langosch (Ed.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon. Volume 3. De Gruyter, Berlin 1943, Col. 404-424.

- Anke Roeder: The Monastery of Minne . In: Gert Woerner (Hrsg.): Kindlers Literatur Lexikon . Volume 4. Zurich, Kindler 1968, p. 574f.

- Tilo Brandis : Middle High German, Middle Low German and Middle Dutch Minnereden. Directory of manuscripts and prints . Beck, Munich 1968, p. 170.

- Walter Blank: The German Minneallegorie . Metzler, Stuttgart 1970, pp. 162-172.

- Ingeborg Glier (Ed.): Artes amandi. Investigation of the history, tradition and typology of German miner speeches . Beck, Munich 1971, ISBN 3-406-02834-9 , pp. 178-184.

- Ingeborg Glier: Monastery of love . In: Kurt Ruh (Ed.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Volume 4. 2nd completely revised edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-11-008838-X , Sp. 1235-1238.

- Sabine Heimann: The monastery of love . In: Rolf Bräuer (ed.): Poetry of the European Middle Ages . Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34563-8 , p. 501f.

- Astrid Wenninger: Was Don Quixote's ancestor a Bavarian? About a literary-archaeological find in the Monastery of Minne . In: Yearbook of the Oswald von Wolkenstein Society . 15, 2005, ISSN 0722-4311 , pp. 251-265.

- Jacob Klingner , Ludger Lieb : Escape from the castle. Reflections on the tension between institutional space and communicative openness in the miner speeches . In: Ricarda Bauschke (Hrsg.): The castle in Minnesang and as an allegory in the German Middle Ages . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-631-51164-7 , p. 156ff.

- Wolfgang Achnitz: "De monte feneris agitur hic". Love as a symbolic code and as an affect in the monastery of love . In: Ricarda Bauschke (Hrsg.): The castle in Minnesang and as an allegory in the German Middle Ages . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-631-51164-7 , pp. 161-186.

Web links

- Liedersaal manuscript - Donaueschingen 104 in the digital collections of the Badische Landesbibliothek

- Cod. Pal. germ. 313

- Codex Dresden M 68, De monte feneris agitur hic begins at Fig. 135.

Individual evidence

- ^ Tilo Brandis: Middle High German, Middle Low German and Middle Dutch Minnereden. Directory of manuscripts and prints . Beck, Munich 1968, p. 170, no. 439.

- ↑ Ingeborg Glier (Ed.): The German literature in the late Middle Ages (1250-1370) . Beck, Munich 1987, p. 77.

- ↑ Heinrich Niewöhner (ed.): The poems of Heinrich the Teichner . Volume I. Berlin 1953, p. LXXXI. Jürgen Schulz-Grobert: "Authors wanted". The author's question as a methodological problem in the area of late medieval couple poetry . In: Joachim Heinzle (Hrsg.): Literary interest formation in the Middle Ages . Stuttgart / Weimar 1993, p. 70.

- ↑ There are a total of 258 leaves and remains of two other leaves. See Marburg Repertory

- ↑ Joseph von Laßberg (ed.): Lieder Saal. This is a collection of old German poems from unprinted sources . Volume 2. o.A. 1822, p. XIXf.

- ↑ Ü .: No horse was ever so fast / that it could have run around the monastery in a whole year. Z. 262-264 of the Donaueschingen Liedersaal manuscript. Quoted from Maria Schierling: "The Monastery of Minne". Edition and investigation . Kümmerle, Göppingen 1980, p. 19.

- ^ Schierling, p. 39, line 869.

- ↑ I'm sure, I don't know what to do with anything . Schierling, p. 40, lines 923f.

- ↑ T: Whoever wants to go [to the monastery] / and adheres to the rule / can grow old here carefree / and still serves God. Schierling, p. 58, lines 1490-1494. Gustav Ehrismann describes this view as the "ethics [...] of knightly humanism". See Dr. Gustav Ehrismann: History of German literature up to the end of the Middle Ages . Volume 2. Beck, Munich 1935, p. 505.

- ↑ "I am stunned when I was caught" Schierling, p. 67, line 1768. "Erhast" as Hapax legomenon refers to the fact that the narrator reacts like a startled rabbit. See Wolfgang Achnitz: "De monte feneris agitur hic". Love as a symbolic code and as an affect in the monastery of love . In: Ricarda Bauschke (Hrsg.): The castle in Minnesang and as an allegory in the German Middle Ages . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2006, p. 179.

- ↑ The so-called St. John's blessing can be understood here as a farewell drink, but is generally the desire for spiritual and physical well-being of the drinker.

- ↑ T: If God lets me live as long as I am, / I will go to the monastery / and keep the rule / and spend my old age in the monastery. Schierling, p. 71, lines 1887-1890.

- ↑ Heinrich Niewöhner: Minnereden and allegories . In: Wolfgang Stammler, Karl Langosch (Ed.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Volume 3. De Gruyter, Berlin 1943, Col. 404.

- ↑ Georg Richter: Contributions to the interpretation and text reconstruction of the Middle High German poem "Kloster der Minne" . Bernhard Paul, Berlin 1895, p. 12.

- ^ Schierling, p. 14, line 107.

- ↑ Schierling, p. 14, lines 112f.

- ↑ I wonder if you think about that tantz sy? Schierling, p. 26, lines 472f.

- ↑ Ü: I asked: “Dear lady, tell me / when does love appear?” / She replied: “Do you not recognize it / when it happens in front of your eyes? / If you can't see love / here in this place / so don't ask about it in the future! ” Schierling, p. 61, lines 1574–1580.

- ↑ a b Ingeborg Glier: Monastery of Minne . In: Kurt Ruh (Ed.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Volume 4. 2nd completely revised edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1983, column 1237.

- ^ Richter, p. 13.

- ↑ Die Winsbekin , v. 34, lines 8-10 and v. 35, line 10. In: Der Winsbeke and the Winsbekin. With comments by M. Haupt . Weidmann'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1845, p. 44.

- ↑ Reference is made to the number 12 and the associated interpretations of the monastery as heavenly Jerusalem on earth. See Blank, pp. 165f .; Matthaei; Schierling, p. 121ff.

- ^ Schierling, p. 20, line 279.

- ↑ Achnitz, p. 168.

- ^ Schierling, p. 14, line 112.

- ↑ Achnitz, p. 170.

- ^ Heinrich Niewöhner: The monastery of love . In: Wolfgang Stammler, Karl Langosch (Ed.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Volume 3. De Gruyter, Berlin 1943, Sp. 397.

- ↑ Anke Roeder: The Monastery of Minne . In: Gert Woerner (Hrsg.): Kindlers Literatur Lexikon . Kindler, Zurich 1968, p. 574.

- ↑ Walter Blank: The German Minneallegorie . Metzler, Stuttgart 1970, p. 163.

- ↑ See also Kurt Matthaei: Das "Weltliche Klösterlein" and the German Minne Allegory . Diss. Marburg 1907.

- ↑ See Achnitz, p. 167.

- ^ Glier: author's lexicon , Sp. 1238.

- ↑ a b Roeder, p. 574.

- ↑ ZB Schierling, lines 725, 780, 839, 1104, 1771.

- ↑ Both cf. Heinrich Niewöhner: Minnered speeches and allegories , Sp. 406.

- ↑ Ingeborg Glier (Ed.): Artes amandi. Investigation of the history, tradition and typology of German miner speeches . Beck, Munich 1971, p. 183.

- ↑ Emil Schaus: The Monastery of Minne . In: ZfdA 38, 1894, p. 367.

- ↑ a b Richter, p. 21.

- ↑ See, inter alia, Schierling, p. 107ff .; Niewöhner: The Monastery of Minne , Sp. 401f.

- ↑ Schaus, p. 366.

- ↑ Ehrismann, p. 505.

- ↑ a b Niewöhner: The Monastery of Minne , Sp. 402.

- ^ Glier: Artes amandi , p. 180.

- ^ Glier: Artes amandi , p. 179.

- ↑ Schaus, p. 366f.

- ↑ Ettal Rule . Kaiser-Ludwig-Selekt No. 520. Bavarian Main State Archives Munich, line 4; see. Hemlock, p. 74.

- ^ Ettaler rule , line 10; Hemlock, p. 75.

- ↑ They wallow in their hats from drunkenness and ... look no further than other games . Ü: You should beware of getting drunk and should not play dice or any other game of money . Ettaler Regel , lines 28f .; Hemlock, p. 77.

- ↑ ez sullen the knights dhein anders varb then wear pla vnd gra vnd the frawen nwr pla. Ü: The knights are not allowed to wear any other colors than blue and gray, the women only blue . Ettaler rule , line 6 f .; Hemlock, p. 75.

- ^ Schierling, p. 17, line 189.

- ^ Schierling, p. 38, line 864.

- ↑ Schierling, p. 58, lines 1471-1474.

- ^ Richter, p. 22.

- ↑ Schierling, p. 24, lines 408-411.

- ↑ Schaus, p. 364.

- ^ Astrid Wenninger: Was Don Quixote's ancestor a Bavarian? About a literary-archaeological find in the Monastery of Minne . In: Yearbook of the Oswald von Wolkenstein Society . 15, 2005, p. 252.

- ↑ Achnitz, p. 175.