Basic Law of Denmark

The Basic Law of Denmark (officially Danmarks Riges Grundlov - "Basic Law of the (King) Kingdom of Denmark") is the Danish constitution and was signed on June 5, 1849 by King Frederik VII . This date has been a national holiday in Denmark since then (alongside the Queen's birthday) and marks the introduction of the constitutional monarchy and the abolition of absolutism , which has existed since its introduction by Frederick III. 1661 existed. It is the hour of birth of democratic Denmark with its 150-year history.

The constitution of 1849 is specifically called Junigrundloven - "the June Basic Law". In Danish usage, one generally speaks of the Grundloven (“the Basic Law”) when referring to today's constitution, which has only been changed insignificantly. It originally had 100 paragraphs, today there are 89. Of these, around 60 are identical to the June Basic Law of 1849. Seven other paragraphs have remained unchanged since the amendment in 1866.

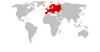

The constitution of 1849 introduced a bicameral parliament , the Rigsdag (Reichstag), which consisted of the Landsting as the upper house and the Folketing as the lower house. The constitution permanently restricted the king's power and ensured basic human rights . With the last change in 1953, the Landsting was abolished and female succession was allowed. Constitutional amendments are generally the subject of a referendum in Denmark . The Danish Basic Law also applies in Greenland and the Faroe Islands , which also have statutes of autonomy.

Constitutional history

The first Danish constitution was the " Royal Law " (Danish Kongelov, the lex regia ) of 1665 and marked the final introduction of absolutism in Denmark by Frederik III. by abolishing the old feudal system and the Reichsrat and Reichstag. Denmark was the only country in Europe that even had a written constitution in absolutism.

After the French Revolution of 1793-94 ended in a bloodbath, liberalism suffered defeat. The ideas of the separation of powers and a social contract were revised and taken up again in a more moderate form after 1814 - from 1830 also in Denmark.

Hopes rested in particular on King Christian VIII , who had given the country a free constitution as a brief king in Norway in 1814. Indeed, in late 1847 there were plans to create a constituent assembly for the kingdom and duchies. In December 1847, Christian VIII commissioned the royal commissioner Peter Georg Bang to draft a new constitution for the entire state, in which the absolute monarchy was also to be abolished. There was a first draft constitution at the beginning of 1848. But before it was actually implemented, Christian VIII died in January 1848. His policy was now continued by his son and successor Frederick VII , who issued a forfatningsreskript (“constitutional decree ”) on January 28th , with the 52 representatives ("experienced men") from Denmark and the duchies should be elected equally to a corresponding constituent assembly. However, the preparatory work for a constitution was interrupted by further events in March 1848.

The March Revolution of 1848 in Paris and Berlin led to the nation-state idea being revived in Denmark. With the March Revolution and the formation of a conservative, nationally liberal government, the so-called March Ministry , on March 22, 1848, the previous enlightened, absolutist monarchy was transformed into a constitutional one. With the new form of government, line ministers have now replaced the previous collegial system. At its head was a responsible minister, in this case Adam Wilhelm Moltke . However, the events also promoted the increasing polarization between German and Danish national liberals with regard to the question of the national ties of the mixed-language Duchy of Schleswig. Shortly after the formation of the March Ministry in Copenhagen, a German-oriented Provisional Government was established in Kiel.

The draft constitution

The previous draft constitution from the beginning of 1848 was not pursued further in view of the March events. Instead, the young priest and minister of culture, Ditlev Gothard Monrad (1811–1887) , who was influenced by national liberalism, wrote the first draft constitution in a three-person committee from June 1848. He took a collection of contemporary constitutions as a model and sketched 80 paragraphs that are similar in structure and basic idea to today's Danish Basic Law. The government draft was later revised linguistically and legally by Orla Lehmann .

The main principle "The form of government is limitedly monarchical" (§ 2) was taken over by Monrad from the Basic Law of Norway of 1814. But he also found a lot of inspiration in the Constitution of Belgium of 1830, and for the section on civil liberties he looked at the United States' constitution States of 1787 with their appendix on the Human Rights Bill of Rights .

The draft stipulates the rights of the constitutional king. He should have real influence. No law should be valid that he had not signed. In addition, the ministers should be elected by the king and not be able to be toppled by parliament.

There should be a bicameral parliament, the Reichstag , consisting of the Landsting and Folketing . There should be a fairly broad right to vote for both. However, a higher age limit for active voting should apply to the Landsting . The members of the Landsting should not collect any diets, but bear their own costs as parliamentarians.

In contrast to the advisory estates, the Reichstag should have legislative power and the right to approve taxes. This should make parliament an effective instrument of power vis-à-vis the king and his government.

The freedom rights should be: religious freedom , freedom of expression and freedom of association , of course subject to public order. A number of class privileges and obligations were abolished. At the same time, general conscription was introduced. The private judicial districts were abolished.

In other paragraphs, laws were promised that would regulate, for example, judicial reform, the organization of the Danish people's church and the liberalization of the economy through freedom of trade .

The draft was discussed and approved by the State Council in July 1848.

The Imperial Assembly

On October 5, 1848, there were general elections for the constituent assembly of the Reich (Den grundlovgivende Rigsforsamling) . All “innocent men over 30 years of age” had the right to vote. This meant all men with their own household and no debt to the state.

The elected members were supplemented by 38 members appointed by the king. That was a quarter of the congregation, which consisted of 152 men. The Imperial Assembly met on October 23, 1848. Its most important task was to deal with the government draft of the Basic Law.

It was not until February 1849 that the Imperial Assembly actually dealt with the draft constitution. The assembly was in doubt as to whether it was right to adopt a constitution only for the Kingdom of Denmark (and not the Duchy of Schleswig ). There were also concerns on the part of wealthy representatives as to where universal suffrage might lead. Monrad, who had not been a minister since November 1848, defended the right to vote in several newspaper articles.

Two camps faced each other: the “Bauernfreunde” (Bondevennerne) and the conservatives. The farmer friends even demanded a unicameral parliament with universal suffrage, while the conservatives demanded greater restrictions on the right to vote for Landsting.

In April, the national liberal lawyers PD Bruun and CM Jespersen submitted a compromise proposal according to which the Reichstag should be a bicameral parliament as planned, but with an indirect election to the Landsting and a lower income limit in order to be elected.

Balthazar Christensen , one of the leaders of the Bauernfreunde, insisted on May 7th that the compromise proposal should be approved in order not to let the Basic Law fail in the end. The Imperial Assembly adopted the Basic Law on May 25, 1849. One of the few opposing votes came from N. F. S. Grundtvig , who opposed the idea of the Landsting, which he regarded as a pure "money chamber, tax chamber and pension chamber".

The widespread approval went back to the "spirit of 1848" (ånden fra 48) in the three-year war (1848–1851) between the German Confederation and Denmark, which strengthened national cohesion.

Transition to democracy

Frederik VII was not particularly in favor of the compromise negotiated. Among other things, he feared the consequences of the exclusive validity only for the Kingdom of Denmark. Nevertheless, on June 5, 1849, he signed the Basic Law. The Basic Law was valid in the Kingdom, but a later expansion to the Duchy of Schleswig for the time after the 1st Schleswig War was expressly kept open in the foreword.

The transition to democracy happened almost imperceptibly. The king continued to elect his ministers, and he was formally vested with executive (executive) and legislative (legislative) power. His position did not suffer from this small but crucial provision in § 18 (now § 13) that his ministers bear full responsibility:

- § 18. The king is not responsible; his person is holy and inviolable. The ministers are responsible for government affairs.

According to § 19 (today § 14), a minister always had to countersign a decision of the king:

- § 19. The king appoints and dismisses his ministers. The signature of the king on decisions relating to legislation and government gives validity to them when accompanied by the signature of a minister. The minister who signed is responsible for the decision.

The idea that ministers would continue to be royal servants was visibly upheld: until 1913, ministers wore noble uniforms and swords like other royal officials.

First Reichstag elections

The active voting age for the Folketing and Landsting remained at 30 years, while the passive voting age for the Folketing was 25 and for the Landsting 40. To be elected to the Landsting, one had to have paid 200 Rigsbankdaler in taxes, or an annual income of 1,200 Rigsbankdaler have. Both active and passive voting rights were reserved for men.

In December 1849 there were the first elections for the Folketing and Landsting. The Folketing members were elected for three years and the Landsting members for eight years. The direct Folketing election happened through majority voting in 100 constituencies. There was also a member from the Faroe Islands . In each district there was only one polling station where voters would gather on election day. First there was a discussion event among the candidates, and then a show of hands was used to vote. In case of doubt, there was an open written vote. The secret right to vote was not introduced until 1901. In cases where there was only one candidate, the vote was dispensed with entirely and the candidate was elected by acclamation.

Under these circumstances, not all citizens were able to take part in the election. In the first election under the June Basic Law, there was a turnout of 32.5% in the constituencies where voting was in writing. The opponents of universal suffrage felt confirmed.

Situation in the duchies

After the 1st Schleswig War ended with a status quo in 1852, the question of the constitutional integration of Schleswig (as a fiefdom of Denmark) and of Holstein and Lauenburg (as member states of the German Confederation) within the now restored Danish state arose. The London Protocol of 1852 adhered to the state as a whole, but also stipulated that Schleswig was not constitutionally bound more closely to Denmark than Holstein. With the bilingual overall state constitution (Helstatsforfatning) from 1855, a constitutional bracket was finally created for Denmark and the three duchies, according to which overarching policy areas such as foreign and financial policy should be dealt with by a joint Imperial Council . The Basic Law of 1849 thus retained its validity in Denmark, but was supplemented at the level of the state as a whole to include the state constitution. The constitutional structure of the entire state constitution meant that Denmark was already run as a constitutional monarchy with the Basic Law introduced in 1849 , while the duchies were still ruled absolutistically with advisory assemblies of estates .

However, after the Bundestag demanded the repeal of the entire state constitution for the states of Holstein and Lauenburg in February 1858, the constitution was only valid in Denmark and Schleswig from November 1858, which was not tenable in the long term. Under the influence of the Danish National Liberals, the entire state constitution was finally replaced in November 1863 by the November constitution , which provided for a two-chamber Reichsrat for Denmark and Schleswig alone. The November Constitution seemed the constitutional dilemma after leaving Holstein and Lauenburg from the former Imperial Council to solve, but also the provisions violated the London Protocol of 1852 and prompted the federal execution in Holstein and Lauenburg from December 1863 and the subsequent German-Danish war from February 1864.

Constitutional amendments

The Basic Law of Denmark was changed in 1866, 1915, 1920 and 1953:

- In 1866, the defeat in the German-Danish War of 1864 contributed to the fact that the electoral rules for the Landsting were tightened, which led to a paralysis of legislative work and thus to many provisional laws.

- In 1915, the tightening of 1866 was relaxed again and women's suffrage was introduced. At the same time, a regulation was introduced according to which not only a simple majority in referendums is sufficient for an amendment to the Basic Law, but 45% of all voters must have voted for it to take effect. As a result, Thorvald Stauning was unable to bring about an amendment to the Basic Law in 1939, although 91.9% voted for and 8.1% against. In absolute terms, it was 966,277 to 19,581, and the former made up only 44.5% of the eligible citizens. Only 11,762 yes votes were missing.

- In 1920 the Basic Law was changed after the annexation of North Schleswig . 96.9% voted for, 3.1% against. At that time there were yes votes of 47.6% of the eligible population, which was enough for the amendment to be accepted.

- The last change in 1953 also achieved the necessary quorum with 45.8% of the electorate entitled to vote. A female succession to the throne was introduced (Section 2 of the Constitution) and the Landsting was abolished (results from Section 28). The 45 percent rule already described has been relaxed to 40% (Section 88 of the Constitution).

In view of the long period of time, these are relatively few changes to the Basic Law, which is due to the fact that the Danish constitution does not contain any particularly detailed regulations, but allows everything to be regulated by other laws, which are of course constantly changed and in some cases are also the subject of referendums. The fathers of the Basic Law created a high hurdle for constitutional amendments with § 88, in which it says:

- § 88. If the Folketing decides on a proposal for a new constitutional provision, and the government joins this matter, new elections for the Folketing are announced. If the proposal is accepted in unchanged form by the newly elected Folketing, it will be submitted to the Folketing voters for approval or rejection within six months. The more detailed rules for this vote are determined in a law. If a majority of the voters and at least 40 percent of all eligible voters have cast their vote for the decision of the Folketing, and if it is confirmed by the King, then it is the Basic Law.

In the June constitution of 1849 the hurdle was a little different:

- Section 100. Proposals for changes in, or additions to, the present Basic Law are submitted by an ordinary Reichstag. If the resolution in this regard is accepted unchanged by the next Ordinary Reichstag, and if this is welcomed by the King, both Houses will be dissolved and both the Folketing and the Landsting will be re-elected in general elections. If the decision is accepted for the third time by the new Reichstag at an ordinary or extraordinary meeting, and this is determined by the king, then it is the Basic Law.

Basic law as a state symbol

In addition to a collection of laws, the Basic Law of Denmark is also a national symbol on roughly the same level as the Dannebrog national flag , the national coat of arms and the royal family , all of which are intended to ensure national cohesion and stability. Every year on June 5th, the Basic Law is honored with lyrical speeches and chants.

The monarch himself, the highest officials and the members of the Folketing take an oath on the Basic Law before taking office.

Structure of the Basic Law

The Basic Law of Denmark is systematically divided into a number of sections. The first set out in detail the main principles of the form of government, the last deal with the rights and freedoms of citizens:

- Form of government (§§ 1–11)

- King and Minister (§§ 12-27)

- Folketing and Legislation (Sections 28–58)

- Jurisdiction (§§ 59-65)

- Volkskirche and religious freedom (§§ 66-70)

- Civil rights and freedoms (§§ 71-84)

- Entry into force and amendment regulations (§§ 85-89)

The constitution thus embraces society as a whole. Even if it initially looks as if power is to be delegated from top to bottom (from the king to the ministers to the Folketing and the citizens), popular sovereignty is one of the most important basic principles. The structure must therefore be understood against the background of its time of origin in the mid-19th century.

Human rights

The human rights in the Basic Law of Denmark go back to the United States Constitution of 1776 and the French Declaration of Human and Civil Rights of 1789.

With the law of April 29, 1992, the European Convention on Human Rights came into force in Denmark. Accordingly, the convention supplements the human rights paragraphs of the Basic Law (§§ 71–84), but does not replace them.

Political parties

The Danish Basic Law does not mention political parties. When the constitution was written, the members of the Reichstag were imagined as independent persons.

In practice, however, it quickly became apparent that common interests led to ever more formal cooperation and thus to party formation. Therefore, a long series of unwritten laws concerning the role of parties in the political system gradually emerged.

Head of State status

When reading the Basic Law, it is important to know that “the king” stands for “the government”, i.e. the symbolic status of the monarch.

The personal legal status for members of the royal family is still regulated by the “royal law”. This means that princes and princesses cannot be tried in public courts until the monarch has given permission. The monarch can set up special royal courts or even sentence members of the royal family. The monarch can also enact royal "house laws" (huslove) .

The paragraphs

Below is a selection of the most relevant and most discussed paragraphs.

Paragraph 3

- § 3. Legislative power rests jointly with the King and the Folketing. The exercising power rests with the king. The judiciary rests with the courts.

This paragraph is fundamental to the modern Western European concept of constitutional law, as it was first formulated by the French philosopher Montesquieu in his teaching on the separation of powers , which was expressed in his great work De l'esprit des lois (The Spirit of Laws ) of 1748 found.

Section 3 forms the basis for the sections on the executive (sections 12-27), legislative (sections 28-58) and judiciary (sections 59-65).

It is noteworthy that in Denmark there has not been a sharp separation of legislative and executive power. Nevertheless, mutual control is always the subject of legal and political disputes in acute situations.

Section 4

- § 4. The Evangelical Lutheran Church is the Danish national church and as such is supported by the state.

Here it is stated that the Danish People's Church is the official church in Denmark. Before the first constitution, the church was a state institution ( state church ), and the constitution of 1849 preserves part of the state element, but emphasizes with the term “people's church” that there are areas that fall under the self-administration of the church. The close ties between the church and the state are the reason why the people's church is sometimes viewed as a kind of state church.

Critics say that a modern society must completely separate church and state in order to introduce real secularism or religious freedom . Some defenders point out that there is religious freedom in Denmark, but not religious equality . See also § 68.

Section 20

- Section 20 (1). Powers to which the Reich authorities are entitled under this Basic Law can be transferred to a more precisely defined extent by law to intergovernmental authorities that have been set up in mutual agreement with other states in order to promote the interstate legal order and cooperation.

This paragraph was designed to allow membership to bodies such as the United Nations and the Council of Europe , but it was later used when Denmark joined the EC (1973). The paragraph says that the government can surrender sovereignty, but it must be clearly defined which sovereignty is surrendered. The paragraph was hotly debated in connection with later EU treaties. EU critics claim that the government violated the Basic Law by giving up unlimited or undefined sovereignty. Minister of State Poul Nyrup Rasmussen was sued by twelve EU critics in 1996 for this reason. The Supreme Court ( Højesteret ) acquitted Rasmussen - and thus also the previous governments - but stated that there were limits to the transfer of sovereignty; Denmark's EU membership is not in conflict with the Basic Law.

Section 68

- Section 68. Nobody is obliged to make a personal contribution to any other worship than one's own.

A group of Catholics had sued the Danish state for violating this paragraph. They alleged that Catholics, members of other religious communities and non-religious citizens indirectly financed the Evangelical Lutheran Church, since the state pays 40% of the pastors' salaries. In addition, the state trains these pastors for free. The case ended in 2006 in defeat for the plaintiffs, as the supreme court argued that no citizen had a personal right to a certain tax distribution.

literature

- Henning Koch, Kristian Hvidt: Danmarks Riges Grundlove. 1949, 1866, 1915, 1953. Christian Ejlers Forlag, København 2000, ISBN 87-7241-912-1 (synopsis of the four constitutional texts ).

- Benito Scocozza and Grethe Jensen: Politics Etbinds Danmarkshistorie. 3rd edition, Politikens Forlag, København 2005. ISBN 87-567-7064-2 , p. 236ff.

Web links

- Danish constitution

- Danmarks Riges Grundlov from June 5, 1849 (Danish)

- Danmarks Riges Grundlov from June 5, 1953 (Danish)

- www.verfassungen.eu: Constitution (German)

- Danish Democracy in: Information from the Folketing, November 15, 2002: (PDF, one page)

swell

- ↑ On January 10, 1661, Friedrich signed the 'Act of Hereditary Solitude of the Empire of Denmark' ( full text )

- ↑ Basic Law Section V. (Sections 45-71)

- ↑ "(...) dog med Forbehold af at Ordng af alt, hvad der vedkommer Hertugdømmet Slesvigs Stilling, beroer indtil Freden er afsluttet.", Quoted from: Thomas Riis (ed.): Forfatningsdokumenter fra Danmark, Norge og Sverige 1809– 1849. Munich 2008

- ↑ Today's § 13 reads: The king is not responsible; his person is inviolable. The ministers are responsible for government affairs. Their responsibility is regulated in more detail by a law.

- ↑ Today's § 14 reads: The King appoints and dismisses the Minister of State and the other ministers. He determines their number and the distribution of resorts among them. The signature of the king on decisions relating to legislation and government gives them validity if they are accompanied by the signature of one or more ministers. Each minister who has signed is responsible for the decision.

- ^ Basic Law of June 5, 1953 ; 'Succession Act of March 27, 1953' (available in the left column)