Setting fire

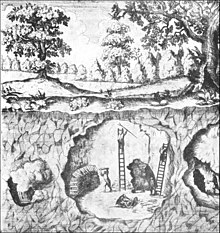

The fire setting is probably the oldest technique in mining for removal of very solid was used rock. The technique was used in many mining regions from ancient times to the early nineteenth century to loosen or blast rock so that the mineral could then be extracted using mallets and irons . The rock was heated by fire and then partly cooled with liquid.

history

The beginnings of setting fire go back to the Stone Age. Traces in the Mur-de-Barrez flint mine in France point to the setting of fires for the extraction of large pieces of flint. In the Bible the method is mentioned in some places (e.g. Hi 28 EU , and Jer 23,29 EU ). The Romans also used this method of mountain cultivation ( Livius Lib. XXI C. 37.).

According to a description by Diodorus Siculus, fire-setting was also common in the gold mines of ancient Egypt. Pliny mentioned in his works that this method was used by the Romans. According to Livy , Hannibal used this method when crossing the Alps. In the late Middle Ages, the setting of fire was used to mine lead. B. was the case in Gurgltal in the Tyrolean Oberland. The open-air museum Knappenwelt Gurgltal gives insights into this era of mining. In Mansfeld shale mining the method was in the years 1720-1730 the irruption of unterschrämtem slate used. In the Harz mountain district, fire- setting was used as an extraction method when mining the massive ore in the Rammelsberg until the end of the 1870s .

The method

So that a dismantling site could be worked on by setting fire, plywood or bumpers were piled up and set on fire. This process sometimes had to be repeated several times. When heated, the rock expands and thermal stresses develop in the rock. This makes it crumbly and cracked. The heated areas are sometimes sprayed with water or vinegar in order to intensify the effect through strong cooling ( thermal shock ). After cooling, the loosened stone slabs can be removed with a wedge pick or mallet and iron. Slabs of stone that have loosened on the roof are broken down using crowbars . The disadvantage is the large consumption of wood, which is why this method was mainly used in wood-rich areas. In addition, this method cannot remove large pieces of rock, only individual shells.

requirements

Firing is not suitable for every type of rock and not every type of ore. A prerequisite for the use of this method is the strength of the rock, because if the rock is already severely fissured, it is not necessary to set the fire, as hammering is sufficient here. Rock with a grainy texture that peels well, such as B. all schisty rock types. But granite and greywacke can also be processed with it. Well-suited types of ore for setting fire are tin and magnetic iron stone . These ores are roasted by setting the fire and can then be smelted better, since additional roasting ( to lower the arsenic gravel content ) is then no longer necessary.

Very wet rock is difficult to work with using fire, as the fire first has to dry the stone and thus loses its effectiveness. Ores with a low melting point were just as unsuitable for fire-setting as deposits where the ores are volatilized by fire. Deposits with a high proportion of mercury are absolutely unsuitable . Silver ores containing arsenic, galena and copper or pyrites are also adversely affected by the setting of the fire.

Fuel

Wood was primarily used as fuel due to its rapid heat generation. The wood was cut into logs to create a rapidly flaming flame. In some mining areas, peat has also been used as a fuel on an experimental basis. However, these attempts did not bring the hoped-for successes. The reason was the insufficient heat development of the peat. At the St. Christoph mine in Saxony, tests were also carried out with coke as fuel. In the French mines of Challanges, coal was used as fuel. Wood was used particularly in the mining regions, where the wood could be obtained very cheaply. So it was z. B. preferably used in wood-rich resin. As a result, setting fire in these regions was two thirds cheaper than drilling and shooting . For the extraction of a cubic of rock you needed, depending on the strength and nature of the rock, up to 18 fathoms of soft wood with a thickness of up to 1.75 cubits .

Firing techniques

Various techniques were used to optimize fire-setting. In some pits, dried pit wood , so-called Tenn , was set on fire. In other pits, chips, which the miner called a beard , were cut from dry wood and set on fire. The flame was directed onto the solid rock through targeted manipulation. To do this, the wood was layered so that it was at right angles to the joint on which the fire was supposed to act. If certain areas were not heated by the fire, the fire was covered by mountains in these areas . In the Harz mining industry, dry, resin-rich wood was used as fuel, as this wood ignites quickly and burns for a long time with a powerful flame. In addition, bundles of light shrubbery and branches and resinous sticks were used.

In order to get a good draft, new logs were either placed on an iron grate or damp wood was placed in the lower part of the fire. Small fires, which were specially stratified, were set up on the spot (where the tunnel is to be driven, location ). When setting fire, three different ways were used to let the fire act on the rock, the roof fire, the side fire and the sole fire. Of all three methods, firing is the easiest method to perform and the most effective. It is for this reason that the method has been used most often. Sole burn is the method that was used the least often.

When firing, the logs are placed hollow, the logs are layered in intersecting layers so that a square pile is created. This pile is known by the miners as a slope or barrier . In the lower layers, the logs are placed with a greater distance and in the upper layers close together. The trays must reach to the roof, you can also stack several trays one meter high next to each other. This makes it possible to attack the roof over a larger area. In the case of a side fire, two logs are placed at right angles to the joint . Up to four layers of intersecting logs are stacked on top of this. A gap of 52 to 104 millimeters is left between the logs of each layer. On top of the pile of wood, a few rows of logs are placed on edge at an angle to the joint. A special oven, the stamping cat, is often used to help. The embossing cat is placed with the narrow side on the joint to be processed and covered with logs, 470 to 628 mm long and 39 to 52 mm thick, and set on fire. The weather draft drives the flames against the thrust. The sole fire was sometimes used when sinking the shaft . Low trays are used for the fire. As far as it is possible due to the slight weather draft, the slopes on the sides and above are covered with mountains.

Firing times

Since the miners could not work in the pits due to the smoke, in some mining regions firing was only carried out on weekends. First of all, over the course of the week, the pieces of wood were piled up into wooden trays at the respective jacking points. On Saturday, the individual wooden trays were set on fire. To do this, the firing points on the upper soles were lit first and then the firing points on the lower soles. This order was necessary so that the miners would not have to work in the smoke of the lower fires. It started at 4 a.m. on a Saturday morning and all the fires were burning on Saturday afternoon. Except for the fire keepers, no one else was allowed in the pit during this time.

The fire resulted in smoke containing sulfur and arsenic, depending on the deposit. As a rule, the fires were set up and measured in such a way that the miners could drive into the mine again for the morning shift on Mondays and break loose the ore. Fires that were still glowing on Monday morning were put out by the fire attendants. If it happened that some piles of wood had not burned enough, they were re-lit and then burned until Tuesday. This delayed the entry of the miners by a day.

Ovens

In some mining regions , a special furnace called the embossing cat was used. This stove consisted of iron rods and two shorter and two higher feet. The feet were connected by four iron bars. The entire frame was covered with strong sheet metal from the outside and from above. This created a square box 2.5 feet long . The mint cat was 1.5 feet wide and one foot high in the front, 2.5 feet wide and 1.5 feet high in the rear. Due to the design, the embossing cat had the shape of a truncated, pyramidal box. The task of the embossing cat was to hold the stoked fire together and to concentrate the flames on one point by means of a targeted air flow from the front.

The fire was worked with forks or forks and racing poles . The two-pronged fork was used to maintain the fire from a safe distance. For this it was provided with a long handle. In addition, loose slabs of stone were removed with the fork so that they would not fall on the embossing cat. The bumpers and racing bars were simple long bars with an iron point or a hook or chisel. The racing poles were also used to break loose rock. As so-called Hülfsgezäh (Hilfsgezähe) were crowbars , scraping , sculpting wedge as well as hammer and chisel used. The prerequisite for this type of targeted firing was a mine building that was adequately ventilated .

A modified version of a stove for setting fire was developed by Hugon in the second half of the 19th century. A fan is set up in front of the kiln. The furnace is set on rollers and can be moved back and forth on rails. The fuel is added to the stove through a door. The furnace is fired with dry wood chips and then fired with coal or coke. The fire is supplied with combustion air through an opening in the front area by the fan. This furnace was in France during tunneling used. The fire is directed through an opening in the back of the furnace, like the tip of a large soldering tube.

Security issues and negative effects

Safety problems arise primarily from the large amount of smoke released by the fire. The additional oxygen consumption is particularly noticeable in mines where there is only minimal draft . In addition, gases are released, especially carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide , which make the air even worse . Depending on the nature of the wood, there is heavy smoke development in the entire mine building. The miners had to wait to pull in until the smoke cleared. For this reason, fires were only allowed to be set in neighboring pits in consultation with the neighboring mine owner and with the approval of the miner .

A major problem in general was therefore the weathering of the smoke produced when the fire was started. Another problem with this method was the large amount of oxygen consumed by the fire, which is why the method was often only used in larger pits . When the fire started, a large amount of heat was generated locally. This great heat, which continued to have an effect even after it had burned down, impaired the miners working there. The unpredictable breaking off of detached rock slabs was also dangerous. These plates suddenly fell in and could injure the miners working there.

Individual evidence

- ^ Johann Karl Gottfried Jacobson: Technological dictionary, alphabetical explanation of all useful mechanical arts, manufactories, factories and craftsmen . Friedrich Nicolai, Berlin and Stettin 1781.

- ↑ a b c d Georg Haupt: The tunnel systems. Guide for miners and tunnel builders, published by Julius Springer, Berlin 1884.

- ↑ FM Feldhaus: The technology of prehistoric times, historical times and primitive peoples. Published by Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig and Berlin 1914.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Albert Serlo: Guide to mining science. First volume, third improved and up to the most recent edition supplemented, published by Julius Springer, Berlin 1878.

- ↑ a b c Wilfried Ließmann: Historical mining in the Harz. 3rd edition, Springer Verlag, Berlin and Heidelberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-540-31327-4 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Wilhelm Leo: Textbook of mining science. Printed and published by G Basse, Quedlinburg 1861.

- ↑ Peter Rosumek: On ancient smelting technology (last accessed on June 8, 2012; PDF; 1.6 MB).

- ^ A b Carl Friedrich Richter: Latest mountain and hut lexicon. First volume, Kleefeldsche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1805.

- ↑ Swen Rinmann: General mining dictionary . Zweyter Theil, Fr. Chr. W. Vogel, Leipzig 1808.

- ^ Emil Stöhr, Emil Treptow: Basics of mining science including processing. Spielhagen & Schurich publishing house, Vienna 1892

- ^ Carl Hartmann: Vademecum for the practical miner and smelter. Second increased edition, published by Richard Neumeister, Leipzig 1859.

- ↑ a b c d Gustav Köhler: Textbook of mining science. Second improved edition, published by Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1887.

- ^ Heinrich Veith: German mountain dictionary with evidence. Published by Wilhelm Gottlieb Korn, Breslau 1871.

- ↑ Description of mining on the Rammelsberge near Goslar. (last accessed on June 8, 2012)

- ↑ Albert Serlo: Guide to mining science. First volume, published by Julius Springer, Berlin 1869.

- ↑ Carl von Scheuchenstuel: IDIOTICON the Austrian mining and metallurgy language. kk court bookseller Wilhelm Braumüller, Vienna 1856.

- ↑ Friedrich Alexander von Humboldt: About the underground types of gas and the means to reduce their disadvantage. Friedrich Vieweg, Braunschweig 1799.

- ^ Georg Agricola: Twelve books on mining and metallurgy . Fifth book, In commission VDI-Verlag GmbH, Berlin.

- ↑ Brief description of the mining in the Rammelsberge and the smelter processes at Communion-Unterharze (last accessed on June 8, 2012)

- ↑ Friedrich Alexander von Humboldt: About the underground types of gas and the means to reduce their disadvantage. Bey Friedrich Vieweg, Braunschweig 1799.

Web links

- Christian Wolkersdorfer: Reports on setting fire. Mine Archaeological Society, accessed May 25, 2012 .

- Michael Klaunzer, Gert Goldenberg, Simon Hye, Gerhard Tomedi: Investigation of the Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age copper ore mining in the Maukental (Mauk E pit). (PDF; 2.9 MB) In: Annual report of the Center for Ancient Cultures 2009. pp. 22–24 , accessed on May 25, 2012 .

- Ronald Symmangk: A few remarks on setting fire and its use in the Ore Mountains. (PDF; 4.1 MB) In: Der Bergknappe 104. 2004, pp. 40–43 , accessed on May 25, 2012 .

- Lander: Overcoming and repairing the »Franzschachtes« and the »Neues Hirtenstollen« in the Binge Geyer. (Pdf, 2.37 MB) Schachtbau Nordhausen, August 2012, accessed on February 16, 2015 .