Twilight of the Idols or How to Philosophize with the Hammer

Twilight of the Idols or How to Philosophize with the Hammer is a late work by Friedrich Nietzsche published in 1889 , in which he summarized essential aspects of his previous thinking. With him he continued the way of revaluing all values and referred to the " idols " of his time, whose twilight he foresaw.

The heterogeneous work contains many metaphysics-critical , art and linguistic-philosophical insights that are of great importance for understanding Nietzsche's late philosophy.

The company name is usually abbreviated with the sign GD .

content

Nietzsche sums up the main themes of his late work in ten sections, introduced by a short foreword.

As he wrote in the autobiographical text Ecce homo , "Götze" refers to what has been called truth so far , the end of which is indicated by the ( metaphor of) twilight: "Götzen-twilight - in German: It comes to an end with the old truth ... "

Nietzsche adds that of the tuning fork to the image of the hammer, which indicates a violent destruction of the old . With it he refers to the diagnostic procedure that the idols questioned in this way can utter “hollow tones”.

The focal points of his criticism include metaphysics and morals , religion and again the phenomenon of decadence , with which Nietzsche had long been concerned and which he had described in various manifestations.

The metaphysical dualism ( dichotomy ) dominates the history of Western culture and philosophy and divides the world into a true and an apparent area. Nietzsche works out phases of the Platonic and Christian , Kantian and positivistic influence of these separations.

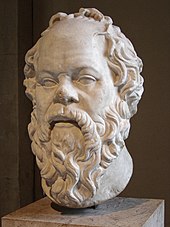

The problem of Socrates

Using the example of Socrates , whom he characterizes as a sick type of decline, Nietzsche delves into the problems of decadence and idiosyncrasy . In his early work, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music , which was still under the spell of Richard Wagner , he had already dealt with the central figure of Greek philosophy and formulated a critique of Socratism . For Nietzsche this was a phenomenon of decay and let tragedy wither away by suppressing the element of the Dionysian . He contrasted the decay, which has continued to the present, with the works of the composer, who was still highly regarded at the time, in which the forces are reconciled .

The ideas of Socrates and Plato represented symptoms of decay of “Greek dissolution”, their value judgments about life were stupid, had no philosophical value and could only be understood as symptoms of a disease. The value of life cannot be estimated, and whoever makes this question a problem as a philosopher, undermines his wisdom.

With Socrates the refined Greek taste changed into the dialectic with which the “ rabble ” came up. Where authority is part of good morals and not to be justified, but to be ordered, the dialectician is considered a “buffoon”. The Socratic irony is possibly an expression of “rabble resentment ”.

The reason in philosophy

In the third section - “Reason in Philosophy” - Nietzsche laments the philosophers' lack of historical meaning, their rejection of becoming and their tendency to confuse “the last and the first”, starting from the highest concepts without considering their origins , yes to reject them. Most believed that the higher should not grow out of the lower. What, like morality, is of the first order, must not have become “ Causa sui ” , with which the concept of God has been reached: the ultimate is posited first, as the cause in itself. Mankind paid dearly to take the "brain ailments of sick cobwebs" seriously.

It is also wrong to distrust the testimony of the senses in favor of an illusory world. What the philosophers had done for millennia were “conceptual mummies”, nothing living came out of their hands. Reason is the cause of a senseless division of the world into two parts. The senses themselves would not lie, but from her testimony made that'll put a lie into it. To separate the world in the sense of Christianity or Kant into a true and an apparent one is a suggestion of decadence.

Morality as anti-nature

In the following chapter, Nietzsche subjects the handling of passions to a critique that works with physiological and psychiatric terms. Above all, the Church, whose practice is hostile to life, behaved wrongly towards the Passions. Instead of asking how desires could be spiritualized and beautified, they were fought. "But attacking passions at their roots means attacking life at their roots."

Nietzsche differentiates between a “healthy” and an “unnatural” morality. Every healthy morality is ruled by an “instinct of life”, while the unnatural, “that is, almost every morality that has been taught so far”, turns against the “instincts of life” and these “soon secretly, soon out loud “judge.

The spiritualization of sensuality, love , is a triumph over Christianity. Enmity, too, has been spiritualized by now understanding its deep value. If the church has strived to destroy its enemies at all times, the “antichrists” would see the advantage precisely in the fact that the church exists. In this “new creation” full of contrasts, “enemies” are more necessary than “friends”, and the value of “inner enemies” has also been recognized: “One is only fertile at the price of being rich in opposites”.

Origin and title

During the summer of 1888, his last creative year characterized by hectic productivity, Nietzsche had given up the plan, which had been cherished since 1885, to publish an extensive major work entitled Will to Power . Now he was working on a similarly broad-based project: The "Revaluation of All Values", from which he was later to draw the first 23 sections for the Antichrist and other works such as Ecce homo , Nietzsche contra Wagner and the poem cycle Dionysus dithyrambs .

Much of the material went into the Twilight of the Idols out of the will to power . The writing, completed in October 1888, was intended to serve as a summary and a “complete general introduction” to his philosophy. In a letter to Franz Overbeck , Nietzsche wrote that he completed the print-ready manuscript within twenty days.

Nietzsche initially had the title “Idleness of a Psychologist” in mind. His friend Peter Gast , however, wrote to him on September 20 that the name sounds too unpretentious. Nietzsche drove his artillery to the "highest mountains", had artillery "like none existed before" and only needed to "shoot blindly to terrify the surrounding area." None of that was "idleness" anymore. If an "incapable person" like a guest could ask, he would like a "more resplendent, more glamorous title."

Nietzsche complied with the request and chose the more effective designation "Götzen-Dämmerung", with which he alluded parodically to Richard Wagner's opera Götterdämmerung .

In a letter to Paul Deussen , Nietzsche wrote that the script gave a “very strict and fine expression of all my philosophical heterodoxy ”, which was hidden under much grace and malice. The Wagnerian and the Twilight of the Idols were real recreations during the "immeasurably difficult" task of revaluing all values . Understanding the radical upheaval would split the "history of mankind in half".

The motto mentioned in the foreword, but not precisely quoted, can be traced back to the Roman poet Aulus Furius Antias .

- A saying, the origin of which I withhold from scholarly curiosity, has long been my motto: "increscunt animi, virescit volnere virtus" or: "The souls grow in the fact that virtue flourishes when wounded."

Meaning and reception

The Twilight of the Idols is one of the controversial, multi-layered works that have most strongly shaped the image of Nietzsche's philosophy.

With his breathless, lofty style, it belongs to the stormy finale of 1888. Nietzsche's (also due to illness) impatience to publish meant that his architectural feeling dwindled, as did the theoretical and systematic tendency that was evident in the previous great works - Beyond Good and Evil and the genealogy of morality - still in outstanding form. As Giorgio Colli puts it, the “paradoxical knot” of its existence, its outmodedness ruined it, an attitude according to which all values held high by the present are despicable. Even if it is difficult to live with this conviction, it becomes practically impossible to impose it on the present, to make the out-of-time in keeping with the times .

The program formulated in the subtitle has often been interpreted and misunderstood in the sense of instructions that encourage violence. The possibility of misuse of the physiological terms for misanthropic " social hygiene " up to the time of National Socialism , which he provoked in the work, has been pointed out several times.

Nietzsche, who had repeatedly dealt with physiological issues (nutrition, diet), seems to have succumbed to the temptation to view decadence from a purely naturalistic perspective. He points to the physiological correspondences of the thinkers who would have represented a wrong, disparaging view of life and emphasizes the ugliness and “low origin” of Socrates. The ugliness is often an expression of an "inhibited development" or appears as a "declining development." Anthropologists among the criminalists would claim that the "typical criminal is ugly [...] but the criminal is a decadent." Was Socrates a criminal? "

This approach leads in the chapter “Forays into something untimely” to the fatal, much-interpreted section “Morality for doctors”, in which the patient is referred to as a “parasite of society”. Sometimes it is "indecent to live even longer." After the "meaning of life, the right to life has been lost", "vegetating [...] in cowardly dependence should result in a contempt of society." A "real one." Saying goodbye "" proudly "is possible when death is freely and at the right time," carried out in the midst of children and witnesses ". All of this appears to be in contrast to "the pathetic and horrible comedy that Christianity drove with the hour of death".

In his essay Nietzsche's Philosophy in the Light of Our Experience , Thomas Mann shed light on Nietzsche's seemingly anti-human derailments and described them as "drunken and therefore basically not serious provocations of the ideal of morality " of which Novalis had spoken. According to Novalis, this ideal has no “more dangerous rival” than that of “highest strength”, which has also been called “the ideal of aesthetic greatness”.

To meet Nietzsche's shrill challenges with moral indignation is inhumane and stupid. In Nietzsche you have a Hamlet fate ahead of you that inspires awe and mercy. With a sensitive registration instrument , he had anticipated the coming imperialism and announced fascism as a “trembling needle”. However, the nefariousness was apt to find its place in the “trash ideology”. The "morality for doctors" of the Götzen-Twilight and some of its breeding and marriage regulations "actually passed into the theory and practice of National Socialism , even if perhaps without knowing reference to it ". Ultimately, however, fascism as a mob-like "culture-penniless" is basically alien to the high spirit of Nietzsche with its noble ideals.

literature

- Eric Blondel: "Finding out idols". Attempt a genealogy of the genealogy. Nietzsche's philosophical a priori and the Christian criticism of Christianity, in: Perspektiven der Philosophie 7 (1981), pp. 51–72.

- Christophe Bourquin: The twilight of the idols as Nietzsche's "Philosophy of the 'quotes'", in: Nietzsche research. Yearbook of the Nietzsche Society 16: Nietzsche in Film, Projections and Götzen Twilights, Berlin 2009, pp. 191–199.

- Marco Brusotti: Götzen -ämmerung or How to philosophize with the hammer (1889) , in: Ders .: From Zarathustra to Ecce homo (1882–1889) , in: Henning Ottmann (Hrsg.): Nietzsche-Handbuch: Leben - Werk - effect . Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2000. ISBN 3-476-01330-8 , pp. 120-137, of which pp. 130-132.

- Mazzino Montinari: Read Nietzsche: Die Götzen -ämmerung , in: Nietzsche Studies 13 (1984), pp. 69–79.

- Andreas Urs Sommer : A philosophical-historical commentary on Nietzsche 's Twilight of the Idols . Problems and Perspectives, in: Perspectives of Philosophy. Neues Jahrbuch, Vol. 35 (2009), pp. 45-66.

- Andreas Urs Sommer: Commentary on Nietzsche's The Wagner Case . Götzendämmerung (= Heidelberg Academy of Sciences (ed.): Historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works, Vol. 6/1). XVII + 698 pages. Berlin / Boston: Walter de Gruyter 2012 ( ISBN 978-3-11-028683-0 ) (new standard commentary).

- Alexander-Maria Zibis: "The warlike in our soul". Nietzsche's Twilight of the Idols as a heroic design of art and life, in: Nietzsche research. Yearbook of the Nietzsche Society 16: Nietzsche in Film, Projections and Götzen Twilights, Berlin 2009, pp. 201–212.

Web links

- Full text

- at Nietzsche Source in the Colli / Montinari edition

- at Zeno.org in the work edition by Karl Schlechta , works in three volumes. Munich 1954, Volume 2, pp. 941ff.

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo , Götzen -ämmerung, Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, Munich and New York 1980, p. 355.

- ↑ Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung , Munich 1991, p. 430.

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, The Problem of Sokrates, Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, Munich and New York 1980, p. 68.

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, The Problem of Sokrates, Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, Munich and New York 1980, p. 70.

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, Die Vernunft in der Philosophie , Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, Munich and New York 1980, pp. 74–79.

- ↑ a b Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, Moral als Widernatur , Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, Munich and New York 1980, p. 83.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, Moral als Unternatur , Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, Munich and New York 1980, p. 84.

- ↑ Nietzsche Handbuch, Götzen-Dämmerung or How to Philosophize with a Hammer , Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2000, Ed. Henning Ottmann, p. 130.

- ↑ http://www.nietzschesource.org/#eKGWB/BVN-1888,1115

- ↑ Martin Heidegger : Nietzsche I , in Heidegger Complete Edition, Vol. 6.1, Klostermann, Frankfurt 1996, p. 205.

- ↑ Quoted from: Friedrich Nietzsche: Commentary on Volumes 1 - 13, Götzen-Dämmerung , Critical Study Edition, Vol. 14, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, p. 410.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, letter to Paul Deussen, Sils-Maria, September 14, 1888, letters, selected by Richard Oehler, Insel, Frankfurt 1993, p. 357.

- ↑ Dt. for example: 'Through injury the souls grow, green (= strengthened) virtue'.

- ^ Giorgio Colli, in: Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung , Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, p. 449.

- ^ Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, Munich 1991, p. 431.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, Das Problem des Sokrates, Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, p. 69.

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, Wanderings of the Untimely, “Moral for Doctors”, Critical Study Edition, Vol. 6, Ed .: Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, dtv, p. 134.

- ↑ Quoted from: Thomas Mann, Nietzsche's Philosophy in the Light of Our Experience , Essays, Volume 6, Fischer, Frankfurt 1997, p. 81.

- ↑ Thomas Mann, Nietzsche's Philosophy in the Light of Our Experience , Essays, Volume 6, Fischer, Frankfurt 1997, p. 83.