Ghost photography

As a ghost photographs ( English spirit photographs ) are photographic images referred to those seemingly spirits , mostly images of deceased persons, are to be seen. Ghost photography was practiced by commercial photographers and spiritualists in the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century , and was particularly popular in the United States and the United Kingdom. The question of whether they could be considered a paranormal phenomenon sparked interest in them. In truth, it was always photo manipulation .

history

Beginnings

The first ghost photographs were made in the early days of photography due to the long exposure times when taking the subject. Objects that were moved during the recording, or people who briefly stepped into the image space , were shown as shadows or only faintly visible on the finished photo. It quickly became apparent that these unintentionally failed images could be marketed as curiosities. In 1856 the Scottish physicist David Brewster described in detail how one could achieve seemingly supernatural effects in stereoscopic recordings by letting people enter the image space shortly before the end of the exposure time. These "ghostly apparitions" were intended for amusement.

United States

The growing interest in spiritualism on the one hand and the strengthening of the religious revival movements on the other hand, combined with the horror of the American Civil War, ensured that people increasingly believed that ghost photography was actually of supernatural origin. The first to successfully market ghost photographs as evidence of the existence of ghosts was the American William H. Mumler. An accidental double exposure of an already used and not thoroughly cleaned photo plate led Mumler to believe that he recognized the ghost of his deceased cousin in a self-portrait. Based on this experience, Mumler set up his own photo studio in Boston in 1862 , where, together with his wife, he offered his services as a medium and creator of real ghost photographs. His photographs became a sensation, which was also reported in Europe.

Mumler's business turned out to be extremely lucrative, but there were increasing voices calling his pictures forgeries. Mumler left Boston in 1868 and opened a studio in New York. There, too, he faced skeptics . In a sensational trial in 1869 he was accused of fraud by PT Barnum, among others . However, the court saw no conclusive evidence of the forgery of the photographs. Mumler's most famous photographs include a photograph taken around 1872 of Mary Todd Lincoln , the widow of US President Abraham Lincoln who was assassinated in 1865 . Although she was introduced to Mumler under a different name and he allegedly did not know her identity, Mumler was able to take a photo that apparently showed Abraham Lincoln and her son Tad, who died the previous year, behind the woman.

Mumler's photographs found numerous imitators in the 1860s and 1870s. Photographers even offered Bibles with ghost photographs of Moses , Abraham, and other Old Testament prophets. The popularity of such images waned in the United States at the end of the 19th century as more and more spiritualist media were exposed as swindlers. Articles in photographic journals detailed various methods, such as double exposures or retouching , that any amateur photographer could use to create ghost photographs.

England

The Briton Richard Boursnell is said to have taken the first ghost photographs as early as 1851, but no photos from this period have survived. It was not until the 1890s that spiritualists became aware of his alleged early works. It is more likely that Boursnell, like other contemporaries, was only inspired by the work of William H. Mumler to take his own photos. The earliest published examples of ghost photographs in England were made by Frederick Hudson in 1872. Benefiting from the continued interest in spiritism and haunted houses in the late Victorian era, Hudson promised his clients to use media such as Georgiana Houghton and Agnes Guppy to create photographs with the "extra" of real ghosts. The naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace was one of Hudson's best-known customers . Even after his first published photos, Hudson was accused of fraud, but was never convicted. Hudson probably used various tricks; Among other things, he is said to have worked with a prepared camera that already contained an image of the supposed ghost as a positive .

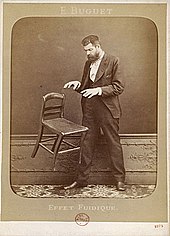

Other photographers have been less successful in hiding their tricks. The French photographer Édouard Isidore Buguet, who himself first appeared as a medium in London and later in Paris, was charged with fraud in 1875. He admitted the forgery of the ghost photographs. In addition, during a search of his studio, the police found life-size dolls, false beards and several hundred prepared photographs. Buguet was sentenced to one year in prison and a fine. His followers, among them the English clergyman William Stainton Moses , suspected a conspiracy of the Catholic Church against the spiritualist Buguet. The Scottish ghost photographer David Duguid, who was active in the 1890s, and the Briton Edward Wyllie, who worked in California at the turn of the century, were also convicted of fraud.

According to Arthur Conan Doyle , who published a History of Spiritualism in 1926 , there were 20 to 30 spiritualists in the UK alone who were ghost photographers in the late 19th century. Their photos differed in the design of the ghostly apparition; some ghost photographs showed geometric patterns as luminous phenomena instead of people. William Stainton Moses referred to such more abstract ghosting as a manifestation of ectoplasm .

There was a revival of ghost photography in the early 20th century by William Hope. Hope had accidentally taken a ghost photograph in 1905. Together with five friends, he then founded a spiritistic circle in Crewe . The circle held séances and specialized in ghost photography, which became increasingly popular. During the First World War , the demand for ghost photography increased as many hoped to get one last memento of loved ones who died in the war.

The first reports appeared as early as 1908, exposing Hope's photos as falsifications. The discovery of X-rays had strengthened the belief in spiritualist circles that the technique of photography could make the otherwise invisible spirit world visible. When the famous researcher William Crookes received a photo of Hope in 1916 , which appeared to show the ghost of his late wife, he was able to prove to Oliver Lodge that the image of Lady Ellen Crookes was assembled from a ten-year-old photograph . Notwithstanding this, Crookes' believer in spiritualism defended Hope's photographs. Hope's final exposure came in 1922, when the British parapsychologist Harry Price investigated methods on behalf of the Society for Psychical Research Hope and was able to prove to him by using previously marked photo plates that the ghost photographs had been manipulated.

Hope's exposure as a fraud sparked a dispute among supporters of spiritism. The writer Arthur Conan Doyle believed in the authenticity of the photographs despite the evidence available, and even penned a defensive pamphlet called The Case for Spirit Photography . Doyle was considered one of the most prominent followers of ghost photography. He was in contact with several photographers and was responsible for the publication of the photographs of the Cottingley Fairies, which were falsified like the ghost photos . The discussion about Hope and his ghost photographs did not end until 1932, when the creation of such photographs was demonstrated at a lecture given to the Society for Psychical Research.

In addition to William Hope, other ghost photographers were exposed as fraudsters by Harry Price in the 1920s. Price summarized the results of his investigations in 1936: "There is no good evidence that a ghost photograph was ever successful." Price received support from other parapsychologists and stage magicians such as Harry Houdini . Further publications in journals such as Scientific American and the increasing evaluation of spiritism as pseudoscience ensured that general interest in ghost photography waned in the late 1920s.

Examples of historical ghost photographs

William H. Mumler's photograph of Mary Lincoln , circa 1872.

Modern variants

After the end of the spiritism movement, ghost photographs only appeared sporadically in the media. Unlike Mumler's or Hope's studio shots, most recent photos are associated with shots in haunted houses, such as the famous shot of the Brown Lady in Raynham Hall in 1936 or a photo of a tourist from Hampton Court Palace published in 2015 showing the spirit of Sibell Penn is supposed to be seen. Most of these recordings can be traced back to double exposures, dirty camera lenses or, in the case of digital photos , sensor stains . Dust particles can also cause light reflections ( backscattering ) in digital recordings that are inexplicable at first glance (so-called orbs or ghost spots ).

In esoteric and parapsychological circles, ghost photographs created by spiritistic media are still distributed as authentic works. A serious scientific discussion like at the beginning of the 20th century is no longer connected with this.

literature

- Cyril Permutt: Beyond the Spectrum: A Survey of Supernormal Photography . Stephens, Cambridge 1983, ISBN 0-85059-620-3 .

- Clément Chéroux, Andreas Fischer, Pierre Apraxine, Denis Canguilhem, Sophie Schmit: The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult . Yale University Press, New Haven 2005, ISBN 0-300-11136-3 .

- Martyn Jolly: Faces of the Living Dead: The Belief in Spirit Photography . British Library, London 2006, ISBN 0-7123-4899-9 .

Web links

- The spirit photographs of William Hope , album with historical photographs from the collection of the National Science and Media Museum.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Colin Harding: G is for ... Ghosts: The Birth and Rise of Spirit Photography . National Science and Media Museum website (accessed October 17, 2020).

- ^ David Brewster: The Stereoscope: Its History, Theory, and Construction . John Murray, London 1856, pp. 205-206.

- ↑ Clive Bloom: Gothic Histories: The Taste for Terror, 1764 to the Present . Continuum, London 2010, ISBN 978-1-8470-6050-1 , p. 153.

- ↑ Jennifer Tucker: Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2005, ISBN 0-8018-7991-4 , pp. 73-74.

- ↑ For a contemporary report on the sensation in London, see Regenburger Zeitung of December 7, 1862, pp. 1346-1347.

- ↑ Louis Kaplan: Ghosts Just for Laughs: Spirit Photography and Debunking Humor . In: Photography Performing Humor (Mieke Bleyen, Liesbeth Decan, eds.). Leuven University Press, Leuven 2019, ISBN 978-94-6270-165-6 , pp. 98-101.

- ^ Jason Emerson: Mary Lincoln for the Ages . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 2019, ISBN 978-0-8093-3675-3 , pp. 42, 91 f., 117.

- ^ R. Gregory Lande: Psychological Consequences of the American Civil War . McFarland, Jefferson 2017, ISBN 978-1-4766-6737-9 , p. 85.

- ↑ Oliver Krüger: Die mediale Religion: Problems and perspectives of religious studies and knowledge-sociological media research . transcript, Bielefeld 2012, ISBN 978-3-8376-1874-7 , p. 18.

- ^ Molly Whittington-Egan: Mrs Guppy Takes A Flight . Neil Wilson, Castle Douglas 2015, ISBN 978-1-906000-87-5 , p. 134.

- ^ Molly Whittington-Egan: Mrs Guppy Takes A Flight . Neil Wilson, Castle Douglas 2015. ISBN 978-1-906000-87-5 , pp. 128-129.

- ^ Molly Whittington-Egan: Mrs Guppy Takes A Flight . Neil Wilson, Castle Douglas 2015. ISBN 978-1-906000-87-5 , pp. 129-130.

- ↑ Milbourne Christopher: Mediums, Mystics & the Occult . Cromwell, New York 1975, ISBN 0-690-00476-1 , pp. 115-116.

- ^ Martyn Jolly: Faces of the Living Dead: The Belief in Spirit Photography . British Library, London 2006, ISBN 0-7123-4899-9 , pp. 20-22.

- ↑ Harry Price: Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter . Causeway Books, New York 1974, ISBN 0-88356-031-3 , S: 168.

- ^ Martyn Jolly: Faces of the Living Dead: The Belief in Spirit Photography . British Library, London 2006, ISBN 0-7123-4899-9 , p. 51.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle: The History of Spiritualism, Volume 2 . Echo Press, Teddington 2006, ISBN 978-1-4068-2306-6 , p. 62.

- ↑ Jennifer Tucker: Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2005, ISBN 0-8018-7991-4 , p. 100.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle: The History of Spiritualism, Volume 2 . Echo Press, Teddington 2006, ISBN 978-1-4068-2306-6 , p. 71.

- ^ The Public Domain Review: The Spirit Photographs of William Hope (accessed October 19, 2020).

- ↑ Chris Webster: Spirit, Ghost and Psychic Photography . In: Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography (John Hannavy, ed.). Routledge, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-97235-2 , p. 1334.

- ^ William Hodson Brock: William Crookes (1832-1919) and the Commercialization of Science . Ashgate, Aldershot 2008, ISBN 978-0-7546-6322-5 , p. 474.

- ↑ Katja Iken: Photo greetings from the beyond . Der Spiegel , December 23, 2011 (accessed October 19, 2020).

- ↑ Kurt Tutschek: Geisterfotografie: Spiritual phenomena of the turn of the century - derStandard.de. In: The Standard. October 31, 2017, accessed on October 31, 2020 (Austrian German).

- ↑ Bernd Stiegler: traces, elves and other phenomena: Conan Doyle and photography . S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2014, ISBN 978-3-10-075145-4 , p. 228.

- ↑ Massimo Polidoro: Photos Of Ghosts: The Burden Of Believing The Unbelievable . In: Skeptical Inquirer , Volume 35, No. 4, 2011. pp. 20-22.

- ↑ Harry Price: Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter , Putnam, London 1936, p. 172.

- ↑ Louis Kaplan: Ghosts Just for Laughs: Spirit Photography and Debunking Humor. In: Photography Performing Humor (Mieke Bleyen, Liesbeth Decan, eds.). Leuven University Press, Leuven 2019, ISBN 978-94-6270-165-6 , p. 102.

- ↑ James Black: The Spirit-Photograph Fraud . In: Scientific American , Vol. 126-127, October 1922. pp. 224-225, 286.

- ↑ Howard Timberlake: The intriguing history of ghost photography , BBC Future, June 30, 2015 (accessed October 19, 2020).

- ^ Annette Hill: Paranormal Media: Audiences, Spirits and Magic in Popular Culture . Routledge, Abingdon 2011, ISBN 978-0-415-54462-7 , p. 45.

- ↑ See for example Thomas Bergmann: Evaluation of ghost photographs . Twilight-Line Verlag, Wasungen 2018, ISBN 978-3-94431-575-1 .