History of the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland

The still existing Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (SP) was founded on October 21, 1888 in Bern . Its predecessor organizations were various workers 'associations, cantonal social democratic parties, the workers' union and, to a certain extent, the Grütliverein .

The first attempts at founding a party: Grütliverein and social democracy

The oldest organization of the Swiss labor movement was the Grütliverein , which was founded in Geneva in 1838 and spread across Switzerland by 1843. Its members described themselves as "Grütlians". They saw their association as a "union of healthy national and social endeavors" and dedicated themselves above all to the education of the workforce . Initially, the Grütliverein mainly consisted of journeymen, later also workers. In the first half of the 19th century, the statutes emphasized the cross-class character of the association. It was only through the statutes of 1849 that the Grütliverein turned more towards politics, first of all in the spirit of the liberal movement, i. H. Democratization and centralization of the Swiss Confederation were a major concern. In the second half of the 19th century, the urban associations increasingly represented a leftist tendency toward socialism and became a "shock troop of the democratic-social renewal movement".

The joining of the leading Grütlian Albert Galeer to the cantonal Social Democratic Party founded in Geneva in 1849 caused a stir , even if this initially had no effect on the association as a whole. The association increasingly represented political concerns of the workforce at national and cantonal level. In 1874 the statutes were changed so that the goal of the association was "the development of political and social progress in Switzerland and the promotion of national awareness on a democratic basis". The Grütliverein played an important role as a representative of the interests of the workers in various voting struggles, for example in the struggle for the Factory Act of 1877 without being clearly Marxist or socialist. The number of members reached a peak in 1890 with around 16,000 members. Various attempts to convert the club into a party failed. However, the association was actually politically represented by some members in the National Council.

A first attempt to found a Social Democratic or Socialist Party in Switzerland was made in Zurich in 1870 on the occasion of a general socialist congress on the initiative of Herman Greulich (1841-1925), the founder and editor of the workers' newspaper Tagwacht . However, the party was unable to hold its own alongside the Grütliverein, the German workers' unions and the sections of the First International . After the disputes between the Marxists and the anarchists in 1872 led to the division of the International, attempts were unsuccessful in 1873 to bring together all the groups of the workers 'movement in the Old Workers' Union. In 1880 the workers 'union was therefore dissolved again at the Olten Congress of the Swiss workers' movement and the Social Democratic Party was re-established. At the same time, the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions and the Workers' Voice were launched as a new party organ. The second founding of the party also proved to be unable to survive due to a lack of suitable leaders and a lack of money.

In 1883 social-democratic-minded representatives of the Grütliverein, trade unionists and representatives of the hapless party came together to form a committee that took on the reorganization of the party. Under the direction of the liberal Bernese lawyer Albert Steck , the party was finally re-established for the third and so far last time in 1888. Actually, this third foundation was only a revival, but since the party had a fundamentally different orientation than in 1880, one can speak of a "new foundation". Steck himself drafted the first party program , which identified the socialization of the means of production as the main goal of the party and was more oriented towards the concept of ethical socialism than Marxism. Therefore, the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland seemed "of the extension at the beginning as a free sense of the fourth estate" in grütlianischer tradition. The Grütliverein continued to exist as a much more important workers' organization alongside the SP.

Development up to the First World War

In 1893 the Grütliverein reformed its statutes under the impression of the strengthening of the socialist orientation of its members so that it defined itself as a «proletarian class organization». The closing of the two organizations finally culminated in the "Solothurn Wedding" in 1902, when the top management of the SP and the Grütliverein merged and the powerful Grütliverein joined the still relatively insignificant SP. It was only through this step that the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland was finally consolidated. Until its dissolution in 1925, the Grütliverein insisted that the social question could be resolved peacefully within the democratic state.

At the political level, the SP was barely successful until the First World War, as the majority voting process in the Swiss parliamentary elections hindered its rise. In the elections in 1890 , Jakob Vogelsanger was elected to the first Social Democratic National Council. Although, according to contemporary sources, around 64,000 of the 350,000 Swiss voters elected Social Democrats, by 1902 only seven Social Democrats had won a seat on the National Council . In the council they formed the so-called "Chapel Greulich", laughed at and suspected of by bourgeois politicians. A member of the Council of States could not be won until 1911. Two popular initiatives to introduce proportional representation in the National Council elections failed in 1900 and 1910. The party was more successful at the communal and cantonal levels. Immediately before the First World War, the number of Social Democratic National Councilors rose to 18 in 1911. In 1913, the SP, together with the Catholic Conservatives, succeeded in launching a new initiative to introduce proportional voting for the National Council , which began on October 13, 1918 People and estates was adopted.

The increase in labor disputes and the increasing number of stewards deployments by the police and the military against the striking or protesting workers increasingly radicalized the social democratic movement. When the party program was to be revised in 1904, the “Marxist” draft program by the orthodox Marxist Otto Lang prevailed. The SP clearly committed itself to Marxism, which was accompanied by strong dogmatization. This gave rise to numerous contradictions to political practice, as a commitment to Swiss democracy could not be reconciled with the theses of Marxism. The party's new principles were not particularly popular with the general public; The ideas of class struggle and internationalism in particular were viewed as "non-Swiss" and earned the SP the reputation of a "party for foreigners" because of its increasing support for German social democracy and the large number of foreigners in the trade unions.

In the party program of 1904, numerous policy areas were addressed that remained topical for the SP until the First World War. The democratization of the army, the abolition of military justice especially in peacetime, social cushioning of the costs of military service for the militiamen, the expansion of freedom of association, the right to strike , the introduction of proportional representation at the federal level, popular elections of the Federal Council, state measures against monopolies and cartels as well as a further expansion of popular rights. In addition, in a Marxist sense, extensive nationalization of parts of the economy, social housing, the introduction of wealth taxes, etc. were called for. However, several party congresses came to the conclusion that class struggle coercive measures such as the general strike in Switzerland were not feasible given their democratic organization.

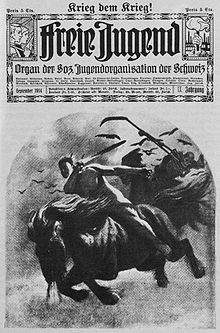

The repeated police operations by the military against strikers also increasingly encouraged anti-militarist and pacifist currents in the working class and thus also in social democracy. Theoretically, Marxism turned against militarism and war, because it saw in them the means of capitalism to continuously increase its power, but at this point in time the SP leadership did not want to categorically oppose national military defense, since it was democratic Switzerland's achievements are definitely worth defending. On the occasion of the discussion about a new federal military organization, the party decided in 1904 to approve it only if guarantees were given against what it considered to be an abusive mobilization of troops in strikes; a democratization of the army was also called for. Since the federal authorities did not comply with these conditions, the SP successfully held a referendum against the military organization, but was defeated in the referendum. The discussion about the question of military organization in the years 1904–1907, which continued until the army reform in 1911, paved the way for a radicalization of the party on the military question. In 1905 an "anti-militarist league" was established with mainly pacifist-minded members, which referred to the anarchist and Christian tradition at the same time. The league was represented in the SP by Charles Naine and Fritz Brupbacher , who with their like-minded people formed only a minority. At the 1906 party congress, the pacifists were clearly defeated with their military-critical advances by 35 to 204 votes and the party acknowledged the need for armed border guards to maintain Swiss neutrality and independence. However, the deployment of the army in the interior was again criticized. Since the resistance to the army reform in 1911 had failed, the SP has submitted an annual motion in the federal councils to suppress military spending altogether. It was argued that there would be no more war in Europe because the solidarity of organized workers in all countries would prevent mobilization. Six months before the outbreak of the First World War, Robert Grimm and Charles Naine introduced a corresponding motion to parliament. This position was held up against the SP for a long time by the bourgeoisie, as the SP parliamentarians shortly afterwards approved the Federal Council's applications for unrestricted military credits.

Overall, in the Swiss labor movement before 1914, the moderate, democratic-evolutionary wing clearly retained the upper hand over radical, revolutionary-class-struggle circles. The religious-social as well as the idealistic-pacifist currents around Leonhard Ragaz , Charles Naine and Ernest-Paul Graber also remained a marginal phenomenon within the party until the war.

Radicalization and division of the labor movement during the First World War

When war broke out, the social democratic faction in the National Council almost unanimously agreed to the powers of the Federal Council and the truce with the bourgeois parties. Only the two radical pacifist national councilors Graber and Naine from Neuchâtel abstained in protest. In view of the outbreak of war, the Socialist International disintegrated and most of the socialists of Europe submitted to the nationalist war programs of the bourgeois governments. The radical socialists, who rejected the war as a betrayal of the interests of the workers, rallied in Switzerland with the young socialists around Willi Munzenberg and around the exiled leaders of the Russian socialists around Lenin , who lived in Switzerland during the war. In 1915 the Bernese socialist Robert Grimm initiated the Zimmerwald movement , which had the aim of reviving the international community and condemned the cooperation of the socialists with the warring parties as " social patriotism ". 1916 an international socialist conference in the Bernese Kiental took place again, but already one of the splitting of the labor movement became apparent in a radical revolutionary wing and a moderate democratic evolutionary wings.

In view of the rise in prices and the as yet non-existent financial compensation for military service (→ wage replacement scheme ), numerous families in particular suffered hardship in the cities, so that protests and demonstrations increased. The workforce became increasingly radicalized, so that a generation change to the younger and more radical Ernst Nobs and Robert Grimm became apparent in the leadership of the SP . The labor movement became increasingly anti-militarist as a result of the war, but also as a result of violent confrontations with the military and the increasing abuse of workers in military service. The emphatically confrontational attitude of the military leadership under General Ulrich Wille intensified this trend. In 1917, the Young Socialists demanded organized conscientious objection by the workers and provoked outrage among the bourgeois parties. Since the SP joined the Zimmerwald movement, in principle it also supported their condemnation of militarism and pacifism. While the active fight against militarism was attributed to the class struggle , pacifism was seen only as an obstruction to the class struggle. An extraordinary party congress was therefore called for 1917 to decide on a revision of the SP's position on Swiss national defense.

The party congress of 1917 finally brought about a change of direction and generation within the SP that would shape the party until the late 1930s. In view of the violent clashes between the army and workers in La Chaux-de-Fonds in May 1917 and the Obersten affair , the party congress adopted by a clear majority an anti-military program that obliged all party representatives to refuse any military credits and to refuse conscription and the Support for conscientious objectors. The SP thus deprived the Swiss military of the legitimation that it was also supported by the labor movement. More moderate representatives of the party such as Herman Greulich, Emil Klöti and Gustav Müller , who had previously occupied a leading position, saw themselves as being in the minority.

In November 1918 there was a trial of strength between the Swiss army and the labor movement when the Olten Action Committee, founded on the initiative of Robert Grimm, called a nationwide general strike to enforce its socio-political demands. This most important socio-political dispute in contemporary Swiss history ended in defeat for the social democrats. Some of the demands, such as the implementation of proportional voting rights, could be implemented, but the strike also brought the bourgeois parties together to form the so-called « citizens' bloc ». The participation of the SP in the government through the inclusion of a representative in the Bundesrat was a long way off. For this, the Liberals who granted Catholic Conservative Party and later the farmers, commercial and Civic Party depending on the political isolation of the SP to strengthen even a seat. The SP could not profit politically from the doubling of its mandates from 20 to 41 in the National Council elections of 1919 , which were carried out for the first time according to proportional representation, as it was faced with an insurmountable bourgeois majority.

Currents of Swiss Social Democracy in the Interwar Period

During the First World War, the directional struggles within the labor movement came to a head in Switzerland. Several currents emerged, some of which split off from the party or were excluded from it. Two main groups can be distinguished within the party: Marco Zanoli describes these as "revolutionary-class struggle" and "evolutionary-democratic" direction, whereby he orients this division on the means that should be used according to the respective direction to achieve the socialist social order. In addition to these two main groups, the pacifist-idealist direction can also be identified. More widespread classifications of the competing groups differentiate between a reformist-minded right wing of the party, a Marxist-minded center and a left wing, which later split off as the Communist Party of Switzerland. Those policy areas in which the differences were greatest can be identified as the so-called "defense question" and the "democracy question". The pair of terms was used during the interwar period to describe the dispute over the recognition of Swiss national defense and the democratic form of government by the Social Democrats, which was waged within the party and between the SP and the bourgeois parties.

The "revolutionary class struggle" direction of social democracy was based entirely on the doctrine of Marxism and the theory of historical materialism, which defined the development of mankind as a history of class struggles. This direction is also referred to in the literature as the system-reforming or revolutionary wing of the SP. He dominated especially among the younger Social Democrats. Members of this party branch rejected the national defense of Switzerland because they saw the socialist movement as an international phenomenon based on the social class of the proletariat and not as a national party with a limited electorate. From this perspective there was no interest in defending a single country, at most in defending a socialist state against capitalist enemies. The army of the bourgeois state of Switzerland was fought in principle because it was always seen as a means of the ruling classes to oppress the workers and to prevent the revolution. The goals of the revolutionary-class struggle-minded direction were the liberation of the Swiss working class by means of violent revolution and the replacement of the Swiss political system, which was described as pseudo-democratic, with the dictatorship of the proletariat . Nevertheless, after the split in the Zimmerwald movement in April 1917, the revolutionary movement stood to the right of the so-called Zimmerwald Left, from which the Third Communist International (Comintern) emerged in 1919 under the leadership of Lenin . Its Swiss supporters split off from the SP under Franz Welti in 1921 as the Communist Party of Switzerland (KPS) after the SP had refused to join the Comintern.

The "evolutionary-democratic" direction united the goal of the liberation of the working class with the idea that a socialist state could only function on a democratic basis, which is why it rejected the introduction of the dictatorship of the proletariat for Switzerland. This grouping is also referred to in the literature as the system-participating, democratic wing of the SP. For the evolutionary group, the revolution ideally proceeded through a democratic takeover of power and not by force - for this reason they committed themselves to national defense as long as Switzerland's social achievements could be defended against a more backward state. The evolutionary group did not reject the army in principle, but criticized existing grievances and strived for its democratization according to the ideas of the time (democratic election of officers by the men, balanced representation of all social classes in the officer corps, democratic control of the army, etc.). Above all, it categorically rejects military deployments against internal, political and economic unrest.

The pacifist-idealist tendency split into a religious (→ religious socialism ) and an idealistically oriented pacifism. Both consistently refused to use force and were therefore against the principle of the dictatorship of the proletariat, against a violent revolution and even against the defense of a socialist Switzerland. The goals of all pacifists were comprehensive disarmament, educating the public about the true face of the war, and establishing effective international arbitration.

Politics in the interwar period until 1935

After the turmoil surrounding the state strike and the takeover of power by the revolutionary class struggle tendency, the question of whether the SP would join the III. International at the center of the debate. Although in 1918 it still seemed as if the SP would turn completely into the radical Marxist camp, the suburb of the party was moved from radical Zurich to more moderate Bern in 1919 with the election of Gustav Müller as party president. Joining the III. International was accordingly rejected. The new party program, which was adopted in Bern in 1920, nonetheless clearly showed class struggle features and aimed to keep the far left of the labor movement in the party. Nevertheless, the extreme left split off in 1921 with the founding of the Swiss Communist Party .

The party program of 1920 again set a clear counterpoint to the bourgeois state on two politically sensitive points. On the one hand national defense and militarism and on the other hand the existing democratic order were rejected by announcing the implementation of the dictatorship of the proletariat in the event of a democratic election victory for the SP. According to the understanding of the time, this meant the introduction of the council system . The fight against militarism had a concrete impact on the fact that the parliamentarians of the SP consistently voted against all military spending and continued to support conscientious objectors and called for the abolition of military justice. In view of the real balance of power in parliament, the successes were limited to the fact that in 1926 the military budget was fixed at 85 million francs through a temporary alliance with the Catholic conservatives. The price for this success was the non-election of Robert Grimm to the Presidium of the National Council.

The initiative to abolish military justice as well as all attempts to influence the pending military or armaments proposals failed at the " citizen block " of the Catholic Conservatives and Liberals. However, it was possible to prevent the civic protective custody initiative and the Lex Häberlin (vote of September 24, 1922), which would have given the bourgeois state legal means to act against socialist propaganda, agitation and strikes. The SP's noisy campaign against militarism had no concrete political consequences, except that it clearly delineated the party from the bourgeois forces. When the SP joined the Socialist Workers' International (SAI) in 1926, the Swiss comrades insisted on their positions on the military and democracy issues, which differed from the social democratic mainstream.

The ongoing political isolation became more and more of a problem for the social democrats in the twenties, because it prevented an effective reform of the social legislation. The trade unions were able to report the introduction of the 48-hour week as a success, but they did not succeed in increasing the taxation of the wealthy (property tax initiative, vote of December 3, 1922), old-age and survivors' insurance or other goals such as a ban of brandy or the lifting of the grain monopoly. Therefore, towards the end of the twenties, the more moderate forces within the SP pushed ever more vociferously for workers to participate in government. To this end, it was considered to force the election of the Federal Council through a popular initiative. On the other hand, through the class struggle positions, the SP was able to successfully prevent the KPS from growing and even oust it again in several cantons. Until 1928 , it was possible to increase the share of the vote nationally to 27.4 percent, the FDP, the then strongest civil party to catch up. With 50 seats, the SP was now the second largest political force in the National Council. The candidacy of the Mayor of Zurich Emil Klöti for a Federal Council seat in 1929 clearly failed due to the bourgeois majority in the Federal Assembly.

While the majority of the revolutionary class struggle tendencies around the political "heavyweight" Robert Grimm in the party leadership of the SP was difficult to break, the more moderate circles in the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions succeeded in taking power as early as 1927. As a visible sign of the political willingness to cooperate, the SGB immediately deleted the dictatorship of the proletariat from its statutes. The electorate indirectly confirmed this course by the fact that Ernst Reinhard, the president of the SP, in contrast to the unionist Robert Bratschi, was no longer confirmed as a member of the National Council. The trade unionists now backed the evolutionary-democratic tendency within the party. The SP's anti-militarist policy also came under increasing pressure because the Social Democrats abroad clearly supported the military in the respective countries.

In the late twenties, the political conflicts between the SP and the communists intensified again. The party leadership vehemently fought the so-called "united front" movement, which wanted to unite the workers' movement under communist leadership. For their part, the communists began to insult the social democrats as "social fascists". The attitude of the SP in the “communist riots” of 1929 and later on the occasion of the strike of the heating fitters in Zurich in 1932 seemed to confirm this thesis, because the social democrats integrated into the local and cantonal government politically supported the police's harsh actions. The sometimes violent conflicts between the Communists and the Social Democrats in Switzerland were limited to the large cities of Geneva, Zurich and Basel. In 1933 the SP's national party congress rejected the KPS's offer of a united front.

In Zurich, the SP, under the leadership of David Farstein , succeeded in gaining a majority in the city government and the local council in 1928. The " Red Zurich " became the flagship of pragmatic social democratic government policy throughout Switzerland. shaped by social policy measures and a forced municipal building policy through the promotion of housing cooperatives. This partially cushioned the worst effects of the global economic crisis , which also hit Switzerland after 1929.

At the national level, after the election of Rudolf Minger , the leader of the still young farmers, trade and citizens' party (BGB), to the Federal Military Department , the SP was confronted with an intensified rearmament policy. Minger systematically pushed for higher military spending and a reorganization of the army. In view of the armament in Italy and France, Minger viewed the expansion of the air force as urgent. The SP demanded that the 20 million francs requested by Minger should instead be used to alleviate the consequences of the economic crisis. Despite strong commitment, however, the SP did not succeed in overturning this highly symbolic template. With Minger's skillful popularization of the military, public opinion was clearly behind the bill. In 1930 Minger managed to bypass the spending limit of 85 million, so that the SP was in ruins with her military policy. The failure of the international disarmament conference in Geneva in 1932 was ultimately the beacon of the special path taken by Swiss social democracy in the military question.

An early integration of social democracy into the political system, which would have been possible in 1932, failed because of the unrest in Geneva in 1932 . The fight against the local fascist movement, led by then Geneva SP President Léon Nicole , escalated into a military operation with 13 dead demonstrators and 70 wounded. Although Nicole was seen as a left deviator within the SP, the SP had to show its sympathy with the "Martyrs of Geneva" and intensify the political struggle against the bourgeois camp. As a short-term consequence of the events, Nicole succeeded in winning a majority for the SP in the cantonal elections and making Geneva the first SP-ruled canton in Switzerland. The aftermath of Geneva poisoned the political climate in Switzerland well into the 1930s and culminated in the vote for the so-called " Lex Häberlin II ". With considerable effort, the SP succeeded for the second time in preventing a “Swiss socialist law ”. The battered right-wing Federal Councilor Heinrich Häberlin , an enemy of the SP, then resigned. Both the SP and the bourgeois parties were thus thrown back into the trenches of the national strike by the events in Geneva. The bourgeois parties also moved closer together again.

After the global economic crisis had also become noticeable in Switzerland from 1930 onwards , the SP began to promote the transition to a planned economy and demanded that the Federal Council take measures to organize the national economy, to control key industries as well as banks and insurance companies. By 1933, the party leadership concretized its ideas to the effect that it wanted to bring together the “workers of all classes” (private workers, small farmers, small tradesmen, intellectuals) in the “united front of all workers”. The federal government should set up a foreign trade monopoly, put comprehensive job creation programs in place, discharge farmers and businesses, all financed by a crisis tax on large assets. In order to win over the petty bourgeoisie, nationalization of the means of production should be avoided. These ideas essentially came from the ideas of constructive socialism in the further development of Hendrik de Man and were known at the time under the title “Plan of Work”.

Over the question of how to deal with the ongoing economic crisis, there was a rift between the SP and the trade unions in 1934, which launched the so-called crisis initiative in competition with the SP's “Work Plan” . This initiative, rejected by the people, was strongly influenced by the economic mastermind of the SGB, the later Federal Councilor Max Weber . In general, under the impression of Hitler's seizure of power in Germany, the trade unions tended more towards an alliance with forces of the political center, as was striven for by the so-called guideline movement (guidelines for economic reconstruction and securing democracy) and the newspaper Nation , than with the SP and the KPS to form an «anti-capitalist defensive front» on the left-wing party spectrum.

The question of how to react to the threats posed by fascism and the deflationary economic policy of the Federal Council also dominated the discussions about a revision of the party program of 1920, which grew stronger from 1933 onwards. The party leadership resisted a revision because it rightly feared that program discussions would only unnecessarily weaken the SP or that a split in the party would even be provoked. Finally, in 1934, with the so-called "Petition of the Five Hundred", the unions forced the elaboration of a new party program which, according to the petition, should appeal to the broadest sections of the working population and should therefore contain an unequivocal commitment by the party to democracy and an unreserved support for national defense.

At the party congress in Lucerne in 1935, the two main wings of the party faced each other irreconcilably under the impression of the fall of social democracy in Austria (→ Austrian civil war ) and the front-line initiative . While the evolutionary-democratic and trade union lines demanded the rapprochement of the SP with the political center and wanted to remove programmatic hurdles, the pacifists and the revolutionary-class struggle wing fought against the betrayal of socialism. The party leadership took drastic measures behind the scenes before the party congress to prevent the threatening split and excluded numerous exponents of the left wing from the party. The defense issue became even more important after 1933, as numerous military affairs cannibalized by the social democratic press raised the fear that the Swiss army and especially the officer corps had already been infiltrated by fascism. At the same time, the debate launched by Federal Councilor Minger about modernizing and arming the army to defend Swiss democracy found more and more supporters among the workers. Leading social democrats also believed that the demise of democracy in Germany and Austria was ultimately partly to blame for the neglect of the military by the respective social democratic parties, and that the SP Switzerland must now learn the lesson from it, and that the military and politicians alike “Conquering” the democratic path The party congress of January 26th and 27th, 1935 finally approved the new party program, which propagated the work plan, recognized democracy unreservedly as a form of government in Switzerland and, under certain conditions, also advocated national defense to protect democracy. At the same time, however, the party congress resolved the no-slogan in the upcoming vote on the new military organization with an extended recruit school. Outsiders interpreted this double decision as a weakness of the SP, but within the party it calmed the anti-militarist forces and prevented the split.

The party program of 1935 is to be understood as a “compromise to the right”, which no longer served the integration of the radical left wing of the party like the program of 1920, but wanted to provide the basis for the “anti-capitalist defensive front” left of the center. With this program, the party leadership intended to transform the SP from a class to a people's party, i.e. an alternative way of gaining a majority in parliament on a democratic basis. The endorsement of national defense was achieved through the logical detour that the SP campaigned for the military defense of democracy against fascism, although the intellectual defense of fascism within as a prerequisite for military defense against outside remained a condition.

literature

- Bernard Degen : Who can co-govern? The integration of the opposition as an act of grace . In: Brigitte Studer (ed.): Etappen des Bundesstaates. State and nation formation in Switzerland, 1848–1998 . Chronos, Zurich 1998, pp. 145–158.

- Bernard Degen: Social Democracy: Counter-Power? Opposition? Federal Council Party? The history of the government participation of the Swiss social democrats . Orell Füssli, Zurich 1993.

- Bernard Degen: Social Democratic Party (SP). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Hermann Dommer and Erich Gruner : Origins and Development of Swiss Social Democracy. Your relationship to nation, internationalism, bourgeoisie, state and legislation, politics and culture . (Workers and the economy in Switzerland 1880–1914; Volume 3). Chronos, Zurich 1988.

- Jann Etter: Army and Public Opinion in the Interwar Period 1918–1939 . Francke, Bern 1972.

- Heinz Egger : The emergence of the Communist Party and the Communist Youth Association of Switzerland . Literature Distribution Cooperative, Zurich 1952.

- Willi Gautschi : The state strike in 1918 . Benziger, Zurich 1968.

- Fritz Giovanoli: The Social Democratic Party of Switzerland. Origin, development and action . Top of the page: Social Democratic Party of the Canton of Bern, 1948.

- Erich Gruner: The workers in Switzerland in the 19th century. Social situation, organization, relationship to employer and state. Francke, Bern 1968.

- Erich Gruner: The parties in Switzerland . Second, revised and expanded edition. First edition 1969. (Helvetica Politica, ser. B, Vol. IV). Francke, Bern 1977.

- Benno Hardmeier: History of Social Democratic Ideas in Switzerland (1920-1945) . Diss. University of Zurich. PG Keller, Winterthur 1957.

- Historical-Biographical Lexicon of Switzerland . Vol. 6. Neuchâtel 1931, pp. 454–458.

- Peter Huber : Communists and Social Democrats in Switzerland 1918–1935. The dispute over the united front in the Zurich and Basel workers . Diss. University of Zurich. Limmat, Zurich 1986.

- Hans Ulrich Jost : Left radicalism in German Switzerland 1914-1918 . Diss. University of Bern. Stämpfli, Bern 1973.

- Karl Lang et al. (Ed.): Solidarity, contradiction, movement. 100 years of the Swiss Social Democratic Party . Limmat, Zurich 1988.

- Otto Lezzi: On the history of the Swiss labor movement . Series of publications by the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions. Bern 1990.

- Markus Mattmüller : Leonhard Ragaz and religious socialism. A biography . Two volumes. Evangelischer Verlag, Zollikon 1957–1968.

- redboox Edition (ed.), agree - but not uniform. 125 years of the Swiss Social Democratic Party. redboox, Zurich 2013.

- Oskar Scheiben: Crisis and Integration. Changes in the political conceptions of the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland 1928–1936. A contribution to the reformism debate . Diss. University of Zurich. Chronos, Zurich 1987.

- Paul Schmid-Ammann: From Revolutionary Class Struggle to Democratic Socialism - The Development of the Swiss Social Democratic Party since 1920 . In: Erich Gruner et al. (Ed.): Max Weber. In the struggle for social justice. Contributions from friends and selections from his work. Max Weber on his 70th birthday, August 2, 1967 . Herbert Lang, Bern 1967, pp. 84-96.

- Paul Schmid-Ammann: The truth about the general strike of 1918. Its causes - its course - its consequences . Zurich: Morgarten, 1968.

- Swiss labor movement. Documents on the situation, organization and struggles of workers from early industrialization to the present . Working group for the history of the workers' movement in Zurich (ed.). 3. Edition. Ex libris, Zurich 1980.

- Marco Zanoli: Between class struggle and spiritual national defense. The Social Democratic Party of Switzerland and the Defense Question 1920–1939 . Zurich Contributions to Security Policy and Conflict Research, No. 69. Zurich 2003.

References

- ↑ For the Grütliverein see Gruner: Die Arbeiter in der Schweiz . Pp. 468-504.

- ↑ Gruner: The workers in Switzerland . P. 475.

- ^ Gruner: The parties of Switzerland . P. 130

- ^ Dommer: Origin and development of Swiss social democracy . P. 131.

- ↑ Gruner: The workers in Switzerland . P. 504.

- ^ Giovanoli: The Social Democratic Party . P. 27.

- ^ Federal Chancellery BK: referendum of November 4, 1900 . ( admin.ch [accessed on October 8, 2018]).

- ↑ Popular initiative «for the proportional representation of the National Council». Rejected in the referendum of October 23, 1910 with 52.5% no votes.

- ↑ Popular initiative “for the proportional representation of the National Council”, adopted in the referendum of August 13, 1918 with 66.8% yes votes and 17 5/2 professional votes.

- ^ Fritz Studer: Memories of the struggles for the introduction of proportional voting , in: Rote Revue , Volume 23 (1943–1944), Issue 3, pp. 81–89. doi: 10.5169 / seals-334944 (PDF)

- ^ Gruner: The parties of Switzerland . P. 131f.

- ↑ Otto Hunziker: Does Switzerland need nor a military defense . Reprint from the Politische Rundschau, 6, 1930. (Writings of the liberal-democratic party of Switzerland, 20). Rorschach: 1930, p. 4f.

- ↑ A. Struthahn: What does the rejection of the defense of the fatherland mean! Socialist Youth Library, No. 10. Swiss Social Democratic Youth Organization (ed.). Zurich: 1917.

- ^ Motions, resolutions and reports on the military question . Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (ed.). Zurich, 1917.

- ↑ Schmid-Amman, The Truth about the General Strike, pp. 386–389.

- ↑ Frick, Social Democracy, pp. 423–427; Hardmeier, History of Social Democratic Ideas, p. 14ff; Huber. Communists and Social Democrats in Switzerland, p. 23f.

- ↑ Discs, Crisis and Integration, pp. 27–50.

- ↑ Frick, Social Democracy, pp. 423–427; Hardmeier, History of Social Democratic Ideas, p. 14ff; Huber. Communists and Social Democrats in Switzerland, p. 23f.

- ↑ Discs, Crisis and Integration, pp. 27–50.

- ↑ Etter, Army and Public Opinion, pp. 101-104.

- ^ Federal popular initiative «Repeal of Military Justice». Referendum of January 30, 1921: 33.6% yes-votes of the electorate and 3 positive votes.

- ↑ Discs, Crisis and Integration, pp. 199f.

- ↑ Etter, Army and Public Opinion, pp. 108f.

- ↑ Zanoli, Between Class Struggle, Pacifism and Spiritual National Defense, pp. 78–81

- ↑ Popular initiative to combat crisis and hardship, referendum of June 2, 1935, rejected with 567,425 no to 425,242 yes votes.

- ^ Zanoli, Between Class Struggle, Pacifism and Spiritual National Defense, p. 131.

- ^ Federal popular initiative "for a total revision of the federal constitution", rejected by those entitled to vote on September 8, 1935 with 72.3% no votes.

- ↑ Zanoli, Between Class Struggle, Pacifism and Spiritual National Defense, p. 147.

- ^ Federal law amending the federal law of April 12, 1907 relating to military organization (reorganization of training). Adopted by those entitled to vote on February 24, 1935 with 54.2% yes-votes.

- ↑ Zanoli, Between Class Struggle, Pacifism and Spiritual National Defense, pp. 162–164.