Goguryeo Wei War

| date | 244-245 |

|---|---|

| place | Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula |

| output | Decisive victory for Cao Wei |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Dongcheon |

|

| Troop strength | |

| 1st: 10,000 2nd: Unknown |

1st: 20,000 2nd: Unknown |

| losses | |

|

6,000? |

8,000 ~ 18,000 |

The Goguryeo Wei War was a series of invasions of the Korean Kingdom of Goguryeo from 244 to 245 by the Chinese state of Cao Wei .

The invasions, in retaliation for the Goguryeo raid in 242, destroyed the Goguryeo capital, Wandu Shancheng , forced the king to flee, and broke ties between the Goguryeo and the other Korean tribes that made up much of Goguryeo's economy. Though the king evaded capture and eventually settled in a new capital, Goguryeo was reduced to such insignificance that the state was not mentioned in Chinese history texts for half a century.

By the time Goguryeo reappeared in the Chinese annals, the state had become a much more powerful political entity - hence the Wei invasion was identified by historians as a turning point in Goguryeo's history, dividing the various stages of Goguryeo's growth. In addition, the second campaign of the war included the largest expedition to date by a Chinese army into Manchuria and therefore made a decisive contribution to providing the first descriptions of the peoples living there.

background

The commonwealth of Goguryeo developed among the peoples of Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula in the 1st and 2nd centuries BC. When the Chinese Han dynasty expanded its control to Northeast Asia and created the four Han command posts . With the growth and centralization of Goguryeo, the contact and conflict between Goguryeo and China increased. Goguryeo consolidated his power by conquering the areas in the north of the peninsula that were under Chinese rule. When the Han dynasty sank into domestic political unrest in the 2nd century AD, the warlord Gongsun Du took control of the command posts of Liaodong (遼東) and Xuantu, which are directly adjacent to Goguryeo. Gongsun Du's faction often argued with the Goguryeo despite initial cooperation and the conflict had reached its climax in the Goguryeo successor dispute of 204, which Gongsun Du's successor Gongsun Kang exploited. Although the candidate, supported by Gongsun Kang, was ultimately defeated, the victor Sansang was forced by Goguryeo to relocate his capital southeast to Wandu Shancheng (today's Ji'an , Jilin ) on the Yalu River , which provided better protection. Gongsun Kang moved in and restored order to the Lelang Headquarters and established the new Daifang Headquarters by dividing the southern part of Lelang.

Compared to the agriculturally rich former capital Jolbon, Wandu Shancheng was in a mountainous region with little arable land. In order to sustain the economy, Wandu Shancheng had to continually withdraw resources from the peoples in the country, which included the Okjeo and Ye tribal communities . The Okjeo are said to have worked as quasi slaves of the Goguryeo king, transporting supplies (such as cloth, fish, salt and other sea products) from the northeast of the peninsula to the Yalu basin, which reflects the regulations that the Goguryeo after the entry von Gongsun Kang had to meet. By the 230s, the Goguryeo had regained their strength from these tributary relationships and regained their presence in the Jolbon region. In 234 the successor state of the Han Dynasty, Cao Wei, made friendly contact with Goguryeo, and in 238 an alliance between Wei and Goguryeo destroyed the common enemy Gongsun Yuan, the last of the Gongsun warlords (see Sima Yi's Liaodong campaign). Wei took over all areas of Gongsun Yuan, including Lelang and Daifang - now Wei's influence extended to the Korean peninsula bordering Goguryeo.

The alliance broke in 242 when King Dongcheon of Goguryeo sacked the Liaodong District in Xi'anping (西安 平; near present-day Dandong , Liaoning) at the mouth of the Yalu River. The motive for the raid, though not entirely clear, was either as a search for new agricultural land or as a contest for control of the nearby "Little River Maek" (小水 貊) tribe identified the Goguryeo, who was known for his superb arches. Since a Goguryeo presence there would cut off the land routes between the Chinese heartland and the peninsula commanderies, the Wei Court reacted very violently to this apparent threat to their control of Lelang and Daifang.

First campaign

The Battle of Liangkou

In response to Goguryeo's aggression, the inspector of You (幽 州刺史) Province, Guanqiu Jian , set out from the Xuantu headquarters for Goguryeo with seven legions - a total of 10,000 infantry and cavalrymen - in 244. From the seat of government in Xuantu (near present-day Shenyang , Liaoning ) the army of Guanqiu Jian moved up the valley of the Suzi River (蘇 子 河), a tributary of the Hunjiang River, up to today's Xinbin County , and from there crossed the watershed in the east and entered the valley of the Hunjiang River. King Dongcheon marched out of his capital, Wandu Shancheng, with 20,000 infantrymen and cavalrymen to face the advancing army. The king's army crossed several river valleys and met at the confluence of the Fu'er River (富爾 江) and the Hunjiang River, a place known as Liangkou (梁 口; today's Jiangkou Village 江口 村 in Tonghua ), on the army of Guanqiu Jian. Liangkou was to become the scene of the first fighting between Guanqiu Jian and King Dongcheon.

There are different sources about the course of the fighting. The later Korean source of the Samguk Sagi states that Guanqiu Jian's army invaded in the eighth lunar month of the year but was defeated twice before winning the decisive battle that drove the king back to the capital. In the first battle, Samguk Sagi said, King Dongcheon's 20,000 foot and horse soldiers faced Guanqiu Jian's 10,000-man army on the Hunjiang River. Goguryeo won this battle and beheaded 3,000 Wei soldiers. The second battle is said to have taken place in a "Valley of the Liangmo" (梁 貊 之 谷), where Goguryeo was victorious again and captured and killed 3,000 other soldiers. The two victories seemed to have risen to the king's head, as he remarked to his generals: "The Wei army, so huge, cannot take on a small force of ours, Guanqiu Jian is a great general of Wei, and today his life is in my hands! " Then he led 5,000 horsemen to lead the attack on Guanqiu Jian, who had squared his troops and were fighting desperately. In the end, 18,000 Goguryeo men were killed in this final battle, and the defeated king fled to the plains of Yalu (鴨 綠 原) with just over a thousand horsemen.

In contrast to this, the almost contemporary "Biography of Guanqiu Jian" in volume 28 of the " Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms ", which contains the Chinese representation of this battle, states that King Dongcheon was repeatedly defeated in the mighty battle at Liangkou and forced to flee . Japanese researcher Hiroshi Ikeuchi points out that the Korean account from the biography of Guanqiu Jian was reworked by reversing the results of the fighting off Liangkou in order to preserve Goguryeo's reputation. The same researcher also points out that the above-mentioned "Valley of the Liangmos" site was fabricated by the biased historian who sympathized with Goguryeo. Nonetheless, both Chinese and Korean sources agree that King Dongcheon eventually lost the Battle of Liangkou and returned to Wandu Shancheng.

The capture of Wandu Shancheng

The Wei army persecuted the evicted Goguyeo army after the Battle of Liangkou. According to the Chinese source "History of the Northern Dynasties", Guanqiu Jian reached Chengxian (赬 峴), which was defined as the current mountain pass Xiaobancha Mountain Ridge (小 板 岔 嶺), also called Banshi Mountain Ridge (板 石嶺). Since the mountainous region made the cavalry ineffective, the Wei Army fixed the horses and chariots there and climbed up to the mountain town of Wandu Shancheng. Guanqiu Jian first stormed the fortress that was defending the capital and then raided the capital, where the Wei army caused much destruction, killing and capturing over thousands of people. In particular, Guanqiu Jian spared the grave and family of Deukrae (得 來), a Goguryeo minister who frequently protested aggression against Wei and starved to death in protest when his advice was ignored. The king and his family fled the capital.

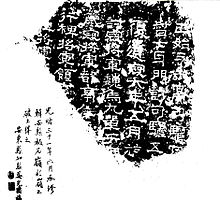

After the capital was subjugated to the Goguryeo, Guanqiu Jian returned with his army to You Province around June 245. On the way back, he had a plaque set up in Chengxian to commemorate his victory, explain the course of events and list the generals involved in the campaign. A fragment of the monument was discovered in 1905, towards the end of the Qing Dynasty, bearing the following destroyed inscription:

In the 3rd year of Zhengshi [? Raided] the Goguryeo 正始 三年 高 句 驪 [? 寇] ... commanded the seven legions and attacked the Goguryeo. In the 5th [? Year] ... 督 七 牙 門 討 句 驪 五 [? 年] ... the remaining enemies again. In the 6th year, the 5th month, he led [his army] back ... 復遣 寇 六年 五月 旋 [? 師] General who destroys intruders, Wuwan Chanyu of Wei ... 討 寇 將軍 魏烏 丸 單于 General who intimidates intruders, chief of the village of Marquis ... 威 寇 將軍 都 亭侯 Expedition major general owns ... 行 裨將 軍 領 ... Major General ... 裨將 軍

Second campaign

Persecution of King Dongcheon by Wang Qi

King Dongcheon had returned to the abandoned capital of Wandu Shancheng after the Wei army withdrew home, but that same year Guanqiu Jian sent Xuantu's Grand Administrator Wang Qi (王 頎) to persecute the king. Since the capital had become heavily devastated and defenseless by the previous campaign, the king and his nobles of several ranks had to flee again to South Okjeo (also known as Dongokjeo, "East Okjeo"). According to the Samguk-Sagi, the king's escape was supported by Mil U (密友), a man from the Eastern Department (東部), when the king's troops at Jukryeong Pass were scattered to the last handful (竹 嶺). Mil U said to the King, "I will go back and keep the enemy at bay while you make good your escape," and held the narrow pass with three or four soldiers while the King set out with a group of friendly troops, to regroup. The king offered a reward to anyone who could get Mil U back to safety, and later Yu Ok-gu (劉 屋 句) found Mil U lying on the ground with serious injuries. The king was so pleased about this that he personally nursed Mil U back to health.

Wandu Shancheng's chase to South Okjeo took the two parties across the Yalu River to North Korea . The exact route of the chase could have passed today's Kanggye , from where there are two options: one to the east through the Rangrim Mountains and then south to today's Changjin; the other follows the Changja River south and then turns east to reach Changjin. From Changjin, the persecutor and the persecuted followed the Changjin River (長 津 江) south until they reached the vast and fertile plain of Hamhung, where the river flowed into East Korea Bay. It was here in Hamhung that the people of South Okjeo thrived, and so King Dongcheon sought refuge here. From Changjin, the persecutor and the persecuted followed the Changjin River (長 津 江) south until they reached the vast and fertile Hamhung Plains , where the river flowed into the East Korea Bay . It was here in Hamhung that the people of southern Okjeo thrived, and so King Dongcheon sought refuge here. The king fled again and the Wei army turned to North Okjeo.

The samguk sagi refers to an event that is said to have occurred in South Okjeo: Yu Yu (紐 由), another man from the Eastern Department, faked King Dongcheon's surrender to stop the persecution of the Wei. Yu Yu, who was carrying groceries and gifts, was admitted to the camp of an unnamed general von Wei. When the general received him, Yu Yu pulled a hidden dagger from under the plates and stabbed the Wei general to death. He was killed by the servants the next moment, but the damage had already been done - the Wei army, which had lost its commander, was thrown into confusion. King Dongcheon took the opportunity to rally his troops and repulsed his enemy. The Wei armies, unable to recover from the confusion, "eventually withdrew from Lelang". No parallel was found in the Chinese records, and Hiroshi Ikeuchi points out its errors: the author of this passage in Samguk Sagi considered the South Okjeo and Lelang regions to be identical, although they are in fact on opposite sides of the peninsula; also the references to the "eastern department" for Yu Yu and Mil U are anachronistic , since Goguryeo did not enter the country until the middle of the Goguryeo dynasty - i. H. after the rule of Dongcheon - divided into departments. As such, Ikeuchi found the samguk sagi stories of the Wei invasion unreliable.

Along the coast of the Sea of Japan , Wang Qi's army made its way to the countries of North Okjeo, which are now believed to be around the Jiandao area. Although there are records that indicate that the king came to the settlement of Maegu in northern Okjeo (買 溝, also called Chiguru 置 溝 婁; in modern-day Yanji ), no one knows what became of the king in northern Okjeo and Wang Qi's army moved further north inland. They turned northwest on the Okjeo- Sushen border , crossed the Mudan River Basin (either via Ning'an or Dunhua ), home of the Yilou people (挹 婁), and crossed the Zhangguangcai Mountains (張廣 才 嶺) into the levels on the other side. Eventually they made their way northwest to the Buyeo Kingdom on the Ashi River in what is now Harbin. Buyeo's regent Wigeo (位居), who acted in the name of the nominal King Maryeo (麻 余 王), formally received the Wei army outside their capital in what is now the Acheng district and replenished their supplies. After exceeding their militaristic scope and losing sight of their goal, Wang Qi's army turned southwest of Buyeo and returned to the Xuantu Headquarters, past what is now the Nong'an District and Kaiyuan District. On their return they had made a tour of Liaodong, North Korea and Manchuria.

The submission of the Ye by Gong Zun and Liu Mao

At the same time, Wang Qi sent a separate force to attack the Ye of East Korea, as they were allied with Goguryeo. The troops, led by the Grand Administrators of Lelang and Daifang, Liu Mao (劉茂) and Gong Zun (弓 遵), started from South Okjeo and moved south through the entire length of the region known as the Seven Circles known from Lingdong (嶺東 七 縣). Six of the seven circles - Dongyi (東 暆), Bunai (不耐; also called Bu'er 不 而), Chantai (蠶 台), Huali (華麗), Yatoumei (邪 頭 昧), Qianmo (前 莫) - were subjugated Liu Mao and Gong Zun, while the remaining circle of Wozu (夭 租 縣), which is identical to Okjeo, had already been subjected to Wang Qi. In particular, the Margrave of Bunai, the most important county of the Seven, was described as having surrendered with all of his tribesmen. The march of Liu Mao and Gong Zun along the east coast of Korea may have brought them as far as Uljin, where the local elders informed them of an inhabited island in the east, an island that could possibly be Ulleungdo . Another inscription was placed in Bunai, supposedly in memory of the deeds of Wang Qi, Liu Mao and Gong Zun during the second campaign; however, unlike the tablet attributed to Guanqiu Jian, this inscription has not been found.

Aftermath and Legacy

Although the king avoided capture, the Wei campaigns did much to weaken the Goguryeo kingdom. First, several thousand Goguryeo were deported and relocated to China. Second, and more importantly, the Okjeo and Ye incursions separated these Goguryeo tributaries from the central ruling structure and brought them back under the influence of the Lelang and Daifang commanders. In this way, Wang Qi and his generals removed a significant part of the Goguryeo economy and dealt Goguryeo a worse blow than Gongsun Kang did forty years ago. The Ye under the Marquis of Bunai were expected to provide provisions and transportation when Lelang and Daifang went to war, and the margrave himself became Ye King of Bunai from the court of Wei in 247 (不耐 濊 王) raised. In addition, Wang Qi's intrusion into Buyeo's territory and the subsequent welcome by the hosts confirmed the friendly relations between Wei and Buyeo, and Buyeo's tribute to Wei is said to have continued annually.

When King Dongcheon returned to Wandu Shancheng, he found that the city was too devastated by war and too close to the border to be a suitable capital. Therefore, he moved his capital 247 to a "walled city on the plains" (平壤 城, Pyeongyangseong) and moved his people and holy shrines while leaving Wandu Shancheng to decay. From this new capital, Goguryeo underwent a major reorganization, particularly with regard to its economic base, to recover from the devastation at the hands of the Wei. With the resources of Okjeo and Ye drained, Goguryeo relied on production in the old capital region of Jolbon, while it looked in other directions for new agricultural land.

Goguryeo's history in the second half of the 3rd century was marked by Goguryeo's attempts to strengthen nearby regions and restore stability when it came into conflict with rebellions and foreign invaders, including again the Wei in 259, in which Goguryeo the Wei at Yangmaek and defeated the Sushen in 280, when Goguryeo launched a counterattack on the Sushen and occupied their capital. According to the Samguk sagi, during the Wei invasion of 259 , King Jungcheon assembled his elite 5,000 cavalry and defeated the invading Wei army in a valley in Yangmaek, killing 8,000 enemies. Goguryeo's fortune rose again during the reign of King Micheon (300-331) when the king took advantage of the weakness of Wei's successor, the Jin Dynasty, and removed the commanderies of Lelang and Daifang from central Chinese control. At this point, Goguryeo was completing a seventy-year recovery period and "transformed from a Chinese border state, which consisted mainly of the looting of the Chinese outposts in the northeast, into a kingdom centered in Korea itself, in which the formerly independent tribal communities of the Okjeo and other peoples merged ".

From a historiographical point of view, the expeditions of the second campaign are significant as they provide detailed information about the various peoples of the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria, such as: B. Goguryeo, Buyeo, Okjeo, Ye and Yilou. The expedition, the scope of which is unprecedented in these regions, brought the Chinese first-hand knowledge of the topography, climate, population, language, manners and customs of these areas and was duly incorporated into the Weilüe texts by the contemporary historian Yu Huan. Although the original Weilüe is now lost, its contents were kept in the Records of the Three Kingdoms, where the accounts of the Goguryeo expedition are included in the "Chapter on the Eastern Barbarians" (東夷 傳, Dongyi Zhuan) - it is considered the most important single Source of information on the culture and society of the early Korean states and peoples.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gardiner 1969: 34.

- ^ Byington 2007: 93.

- ^ Barnes 2001: 23.

- ^ Byington 2007: 93-94.

- ↑ Barnes 2001: 20.

- ↑ Tennant 1996: 22. Original quote: "... Capital on the central reaches of the Yalu near the modern Chinese city of Ji'an, which is called 'Hwando'. Through the development of both their iron weapons and their political organization they had one Reached the stage in which, in the turmoil that accompanied the collapse of the Han Empire, they were able to threaten the Chinese colonies now under nominal control ... ".

- ↑ Gardiner 1972a: 69-70.

- ^ Byington 2007: 91-92.

- ↑ Gardiner 1972a: 90.

- ↑ Gardiner 1972a: 89.

- ^ Byington 2007: 92.

- ↑ Gardiner 1972b: 162.

- ↑ a b Tennant 1996: 22. Original quote: "Wei. In 242 under King Tongch'n they attacked a Chinese fortress near the mouth of the Yalu in order to cut off the land route via Liao. In return, the Wei 244 invaded the country one and looted Hwando ".

- ↑ a b Barnes 2001: 25.

- ↑ Gardiner 1972b: 189-90 note 66.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 75, 77.

- ↑ Ikeuchi 1929: 80.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 111.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 113.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 115.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 81.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 85.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 75.

- ↑ Translation from Ikeuchi 1929: 77-78 with minor differences in ranked title translations and romanizations.

- ↑ Ikeuchi 1929: 78.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 87, 94.

- ^ Hubert and Weems 1999: 58.

- ↑ a b Ikeuchi 1929: 87.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 88.

- ^ A b Hubert and Weems 1999: 59.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 116.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 117.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 118.

- ↑ Ikeuchi 1929: 90.

- ↑ Ikeuchi 1929: 97-98.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 105.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 106.

- ↑ Ikeuchi 1929: 92-94.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 95.

- ↑ Ikeuchi 1929: 91, 95.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 95-96.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 95-96.

- ↑ Gardiner 1972b: 175.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 98, note 1.

- ↑ The exact location of this new capital, as described by the Samguk Saga, is up for debate. Hubert literally perceived the place as Pyongyang (Hubert and Weems 1999: 59). Byington concluded that Pyongyang was still in the Wei-administered Lelang and therefore excluded Pyongyang as a candidate. He argued that the capital should be Gungnae Fortress - although he admits that this view is not widely accepted in contemporary science (Byington 2007: 94). Ikeuchi considered the entire passage on resettlement to be an invention of the historian (Ikeuchi 1929: 119).

- ↑ a b c Byington 2007: 94.

- ^ Byington 2007: 93, note 21.

- ^ Byington 2007: 95.

- ↑ Henthorn 1971: 29.

- ↑ Kim Bu-sik. Samguk saga. 17. "十二年 冬 十二月 王 畋 于 杜訥 之 谷 魏 將 尉遲 楷 名 犯 長陵 諱 將兵 來 伐 伐 簡 精騎 精騎 五千 戰 於 梁 貊 之 谷 敗 之 斬首 斬首 八 千餘 級". Ikeuchi (1929) questioned the authenticity of the records of the Wei invasion, as the Wei commander was listed as Yuchi Kai (尉遲 楷) in the Samguk Saga. Ikeuchi argued that the Wei commander's name might be anachronistic as the surname Yuchi was not mentioned in the Chinese records before 386. See Ikeuchi 1929: 114.

- ^ Byington 2007: 96.

- ↑ Barnes 2001: 24-25, cited by Gardiner 1964: 428.

- ^ Ikeuchi 1929: 101.

literature

- Barnes, Gina Lee. State formation in Korea: historical and archaeological perspectives . Routledge , 2001. ISBN 0-7007-1323-9 .

- Byington, Mark E. "Control or Conquer? Kogury's Relations with States and Peoples in Manchuria," Journal of Northeast Asian History Volume 4, Number 1 (June 2007): 83-117 .: 83-117.

- Gardiner, KHJ The Origin and Rise of the Korean Kingdom of Koguryǒ from the First Century BC to 313 AD . Ph.D. thesis, University of London , 1964.

- Gardiner, KHJ The early history of Korea: the historical development of the peninsula up to the introduction of Buddhism in the fourth century AD . Canberra , Center of Oriental Studies in association with the Australian National University Press, 1969. ISBN 0-7081-0257-3 .

- Gardiner, KHJ " The Kung-sun Warlords of Liao-tung (189-238) ". Papers on Far Eastern History 5 (Canberra, March 1972). 59-107.

- Gardiner, KHJ " The Kung-sun Warlords of Liao-tung (189-238) - Continued ". Papers on Far Eastern History 6 (Canberra, September 1972). 141-201.

- Henthorn, William E. A History of Korea . The Free Press, 1971.

- Hubert, Homer B. & Weems, Clarence Norwood (Ed.) History of Korea Volume 1. Curzon Press, 1999. ISBN 0-7007-0700-X .

- Ikeuchi, Hiroshi. "The Chinese Expeditions to Manchuria under the Wei Dynasty," Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 4 (1929): 71-119.

- Charles Roger Tennant : A history of Korea , illustrated. Edition, Kegan Paul International, 1996, ISBN 0-7103-0532-X (accessed February 9, 2012).