Croissant saddle

As croissants saddle is riding saddle Roman cavalrymen called. This is named for the so-called croissants, leather or bronze stiffeners on the sides of the seats, which are intended to ensure a stable hold in the saddle.

Pictorial representations

Visual traditions help with the reconstruction of the Roman military saddle. The largely lifelike representations on the tombstones of Roman cavalrymen proved to be particularly useful . Although minor changes are also possible here for artistic reasons (for example the optical downsizing of functional parts or the decoration of decorative elements), the members of the military were fundamentally interested in having themselves depicted as authentically as possible, as they also expressed a sense of class.

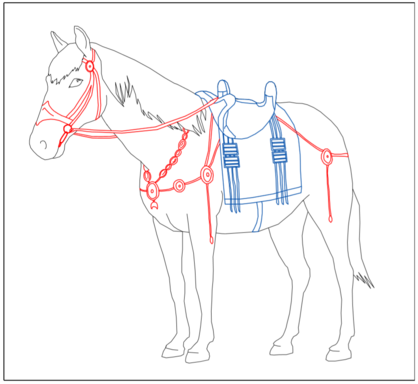

Such soldier grave stones almost always represent rider and horse in profile . The saddle consists of a seat resting on the horse's back and is occasionally supplemented by a more or less long hanging, material-looking saddle cloth. Two knob-shaped elevations, the so-called croissants, can be found on the front and back of the saddles. The front saddle horns stood out at a slightly flatter angle and secured the rider's thighs from slipping, the rear ones were almost upright and secured the buttocks. Sometimes they are shortened to a semicircle in perspective. The chest and tail straps that hold the saddle in place are usually also clearly visible. Additional straps can hang from the sides of the saddlecloth.

What the pictorial tradition is unable to do, is to clarify how the saddle was constructed, i.e. whether the croissants were soft and flexible or stiff, whether the leather seat was mounted on a saddle tree or how the belts were guided around the horse's stomach .

Archaeological finds

Saddle covers

The discovery of a leather saddle cover from the Praetorium Agrippinae fort in today's Valkenburg (South Holland) proved to be trend-setting for archaeological research . As the excavation area was below the water table, the conditions were excellent for the conservation of organic remains. The saddle cover consists of a flap made of goatskin . Characteristic here are the two tongue-shaped bulges on the opposite sides of the leather strip. By adding another tongue-shaped counterpart, as was also discovered in the fort, they formed the saddle horns. Below the horns, the saddle cover often had a few crescent-shaped holes that seem to be related to the treble straps. Exactly how the straps were passed through the holes is unclear - their curved shape is a typical feature of the saddle covers.

The find from Valkenburg made it possible to identify further leather fragments as saddle components in the last decades, including a very similar piece from Vindolanda (GB).

Bronze saddle croissants

The gradual gain in knowledge in archaeological research through pictorial representations of saddles and leather covers made it possible to identify a further group of finds - the metal saddle horns. These consisted of bronze sheet that was driven into a half-shell shape.

Occasionally, entire sets were found in which the front horns were I-shaped and the rear horns were mirror-inverted L-shaped. At the edges they have rows of holes punched through which they were sewn or nailed to the saddle. The finds so far date from the Augustan period ( Haltern , Asciburgium ) to the 2nd century AD ( Newstead , GB). Some specimens have incisions on the concave inside, which are interpreted as owner inscriptions. Markings by the saddler would also be possible . This would be particularly conceivable if the croissants, as is often assumed due to the large variety of shapes, are custom-made. Some pieces also have decorative beads on the edge and others do not. In a single set, residues of leather were found on the outside, which indicate a leather cover.

Saddle girth fittings

In the pictorial representations of Roman cavalrymen, leather straps can often be seen hanging down below the saddle horns. Since they usually come in three strands, they are known as triplet or triplet belts. Their exact purpose can no longer be clearly reconstructed - perhaps they were used to hold the croissants in place.

On the other hand, the saddle girth fittings that held the straps together are archaeologically well verifiable. They can be dated through their decorating technique. Early Tiberian-Claudian fittings consist of simple, rectangular metal plates that are occasionally openwork or tin-plated. From the later first century onwards, the basic form varied more, with drift patterns and niello décor also appearing . Such specimens are made of bronze and are often also silver-plated. They were attached to the treble straps using metal strips on the back through which a rivet was driven.

Saddle belt buckles

Saddle belt buckles are basically no different in shape from other Roman belt buckles. They are only referred to as such because of their striking size of around 70 mm in width. They were used to fasten the saddle girth around the horse's stomach. How exactly these belts were constructed and fastened is not known; clear, pictorial representations are not yet available.

reconstruction

There are some uncertainties in reconstructing the Roman cavalry saddle; In principle, however, it can be said that the "croissants" that lie close to the body should ensure a firm fit. Instead of stirrups, which were not yet known in the Roman Empire, they enabled the rider to shift his weight in the saddle. The Dutch archaeologist Groenman-van Waateringe ventured a first reconstruction in the sixties using the leather finds from Valkenburg. She interpreted the side panels as loosely hanging saddle flaps and assumed that the horns were reinforced with metal or wood. Whether the leather cover was fixed on a wooden construction or whether it lay directly on the saddlecloth is open.

Connolly, on the other hand, considers a saddle tree to be essential in order to divert the cavalryman's weight from the horse's sensitive spine onto his flanks and at the same time to allow the rider to exert pressure on the animal's costal arches with his thighs. The experimental archaeologist sees his thesis confirmed by the rows of seams on the edges of the leather flap, which in his opinion resulted from the leather being pulled onto a wooden frame and sewn together at the overlapping points. In the 1980s, Connolly teamed up with leather specialist van Driel-Murray to further investigate the question of the construction of the saddle. In the meantime, his German colleague Junkelmann had a saddle made with soft padding and tested it in practice. Junkelmann argued that such a saddle fits every horse and is more comfortable for long distance rides. He sees the uneven load on the horse's back as preventable by appropriate padding. Connolly and van Driel-Murray, on the other hand, consider the creases they found in the leather finds to be clear evidence that the leather was pulled up on a saddle tree. Two replicas made with a saddle tree seem to confirm this - they show the same signs of use as the archaeological finds. Only the shape of the wooden structure is unclear. Such a saddle would also have to be individually adapted to each horse in order not to chafe. Since it appears that the bronze horns, which vary considerably in shape and size, are made to measure, this is quite conceivable for the saddle itself.

The saddle horns pose further puzzles. It is noticeable that the metal croissants found so far were always significantly larger than the leather ones. In this respect, the bronze bowls could not have served as a shaping base for the subsequently pulled leather. The other way around - the bronze plates as external reinforcement for soft leather horns - the reconstruction would not be plausible, since the rows of holes in the bronze horns do not correspond with the seams of the leather finds. Both types of finds can therefore hardly be assigned to a single type of saddle. One possibility would therefore be that it was a question of the components of two different types of saddles: One with smaller, stuffed or wood-reinforced leather horns and one with rigid, large bronze horns

Connolly suspected on the basis of his replicas that the saddle type with the high horns, similar to the medieval splendor saddle, had a shock-absorbing effect and was therefore developed for direct combat use, while the small-horned type was more suitable for long distance rides .

Dissemination and dating

It is unclear where exactly the croissant saddle was invented. The earliest clear evidence of the use of the saddle is a depiction on the Julier mausoleum in St. Rémy in the south of France . A riderless horse of a defeated, Celtic warrior is shown, which carries a saddle with the characteristic horns on its back. It seems obvious that the croissant saddle was developed in the horse affine, Celtic culture. Since the Celts of the late La Tène period had lively trade contacts, a takeover by other ethnic groups is also conceivable.

With the conquest by the Romans, the Celtic equestrian associations were incorporated into the Roman army and thus the croissant saddle found its way into the military. The now considerable number of bronze croissants has been found testifies to their frequency. But the saddle was also widely used beyond the borders of the empire: pictorial traditions show that it was also used by the Parthians and the Sassanids of late antiquity . During the fourth century, the croissant saddle gradually disappears. In the eastern Sassanid empire it is immediately replaced by a saddle with stirrups ; in the west this type is only detectable much later.

literature

- Mike C. Bishop: Cavalry equipment of the Roman Army in the first century AD In: Jonathan C. Coulston (Ed.): Military Equipment and the Identity of Roman Soldiers . Proceedings of the Fourth Roman Military Equipment Conference (= BAR International Series. Volume 394). Oxford 1988, pp. 67-195.

- Peter Connolly : Greece and Rome at war. Macdonald Phoebus Ltd., London 1981.

- Peter Connolly: The Roman Saddle . In: Michael Dawson (Ed.): Roman Military Equipment. The Accoutrements of War (= BAR International Series. Volume 336). Oxford 1987, pp. 7-27.

- Peter Connolly: Tiberius Claudius Maximus - The Cavalryman . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1988.

- Peter Connolly, Carol van Driel-Murray: The Roman Cavalry Saddle. In: Britannia . Volume 22, 1991, pp. 33-50.

- Carol van Driel-Murray, Peter Connolly, John Duckham: Roman Saddles: Archeology and Experiment 20 Years On . In: Lauren Adams Gilmour (ed.): In the Saddle: An Exploration of the Saddle Through History. Archetype, London 2004, pp. 1-20.

- Jochen Giesler: Reconstruction of a saddle from the Franconian Graeberfeld von Wesel-Bislich . In: Alfried Wieczorek et al. (Ed.): The Franks, trailblazers in Europe. 1500 years ago: King Clovis and his heirs. Exhibition catalog Mannheim 1996–97. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 808-811.

- Willy Groenman-van Waateringe: Romeins lederwerk uit Valkenburg. JB Wolters, Groningen 1967.

- Georgina Herrmann: Parthian and Sasanian Saddlery: New Light from the Roman West . In: Leon de Meyer, Ernie Haerinck (eds.): Archaeologia Iranica et Orientalis. Miscellanea in Honorem Louis Vanden Berghe. Peeters, Gent 1989, pp. 757-809.

- Marcus Junkelmann : Roman Cavalry - Equites Alae. The combat equipment of the Roman horsemen in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. (= Writings of the Limes Museum Aalen. Volume 42). Limes Museum Aalen, Aalen 1989.

- Marcus Junkelmann: The riders of Rome 1–3 (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 45, 49, 53). Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1990–1992.

- Mathilde Schleiermacher: Roman equestrian tombstones. The imperial reliefs of the triumphant rider (= treatises on art, music and literary studies. Volume 338). Bouvier, Bonn 1984.

Web links

- Photos of a reconstructed croissant saddle with saddle tree (after Connolly)

- Photos of a set of bronze saddle horns from Newstead

- Photo of a set of girth fittings

Individual evidence

-

↑ A concise overview of the surviving pictorial representations on equestrian tombstones from the early imperial era is provided by:

MC Bishop: Cavalry equipment of the Roman army in the first century AD In: JC Coulston: Military Equipment and the Identity of Roman Soldiers . Proceedings of the Fourth Roman Military Equipment Conference, BAR International Series 394 (Oxford 1988), pp. 67-195. - ↑ See Deschler-Erb et al. 2012, Finds from Asciburgium, p. 78.

- ↑ See Connolly, van Driel-Murray 1991, p. 44 f.

- ↑ Cf. Bishop 1988, p. 110.

- ↑ See Connolly 1987, p. 7.

- ↑ See Groenman-van Waateringe 1974, p. 72.

- ↑ See Connolly 1987, p. 16.

- ↑ See Connolly, van Driel-Murray 1991, pp. 46-48.

- ↑ See Connolly 1981, p. 236

- ↑ See Herrmann, 1989, pp. 757-809.