Hanns Georg Heintschel-Heinegg

Hanns Georg Heintschel-Heinegg (born September 5, 1919 in Kněžice , Czechoslovakia , † December 5, 1944 in Vienna , Austria ) was an Austrian poet , theology student and resistance fighter against National Socialism .

Career

Hanns Georg Heintschel-Heinegg came from a family of Austrian woolen goods manufacturers originally from Heinersdorf an der Tafelfichte . He was born in the Kněžice Castle in the Bohemian Forest , which the family acquired in 1897. In 1906 his father Wolfgang Heintschel von Heinegg moved from Vienna to the renovated Kněžice Castle. In 1926 his parents had to sell their goods Kněžice, Žíkov and Strunkov because of excessive indebtedness. The family moved to Vienna with their three daughters and their son, where he attended school. In the 1930s he came to the Theresianum , where he dealt early on with German-language literature and graduated in 1937 . He then entered the Canisianum seminary in Innsbruck . Soon after the connection of Austria to the German Reich in 1938 he had to cancel the study of theology and the resistance group joined in Vienna Austrian Freedom Movement to Roman Karl Scholz on.

In 1940 the freedom movement around Father Scholz was betrayed to the Gestapo by one of its members, the castle actor Otto Hartmann . On July 23, 1940, Heintschel-Heinegg was arrested along with the other leading members of the three aforementioned resistance movements. Heintschel-Heinegg and many of his like-minded people were relocated to Anrath at the beginning of July 1941. The monotony of his work, gluing 1,600 envelopes a day and the writing ban imposed on him, mean an extremely heavy burden for Heintschel-Heinegg:

- If I do not want to lie, I must also confess that I am in the greatest spiritual need: in the need of not being allowed to write down a word from the legions of thoughts about art, science and human life, which roaringly fill me, but which now torment me [...].

At the beginning of November 1941, triggered by the tragic death of Father Bernhard Burgstaller , abbot of the Austrian Cistercian monastery Wilhering , Heintschel-Heinegg was relocated to Krefeld . His stay in the Krefeld prison in particular, but also his second time in Anrath from March 1943, were once again places of rich poetry. Although the Krefeld time also brought a lot of hardship - the prisoners stayed, for example. For example, she was tied up in her cells during the air raids - for Heintschel-Heinegg it seemed to have come with some relief: more time for free activity is reflected in notebooks full of thoughts. From March 1943 back in Anrath prison, as his fellow inmate Heinrich Zeder referred to as the “Hell of Anrath”, the time of “distrust and discomfort” began again for Heintschel-Heinegg: Heintschel-Heinegg writes:

- I have no permission to study or my own writing materials, so that the day, filled to the brim with eleven hours of work and nocturnal restlessness, is gray on gray. The few poems are made very makeshift and can no longer be carefully written down.

After being transferred to various camps and prisons, he was sentenced to death by a people's court meeting in Vienna in February 1944 and executed on December 5, 1944. The execution was described in detail by fellow inmates: After receiving communion, the prisoners were picked up for execution at around 6 p.m. When the death row inmate has left the door, two guards take him to the middle, the pastor steps on his right side - the prison pastor had already said goodbye - and so it goes through the long corridor to the door of the execution room. There the delinquent is received by the executioners, the clergyman stays behind. Then you find yourself in a room lit only by electric light, which is divided into two parts by a black curtain. The senior public prosecutor sits in the front part with the enforcement commission . He asks: 'Are you the gentleman? Yes? The death sentence passed against you by the People's Court is now being carried out. ' Then the executioners jerk the delinquent's feet backwards, he falls face down into a large adhesive plaster that closes his mouth, and he is thrown onto a trundle bed that is in contact with the guillotine. This board slides along two short rails. Then, directly under the ax , a spring is released, the 45 kg knife of the guillotine falls down with a 300 kg drop weight and separates the head from the torso. [...] All in all, the execution takes barely a minute.

Appreciation

The Catholic Church accepted Hanns Georg von Heintschel-Heinegg as a witness of faith in the German martyrology of the 20th century .

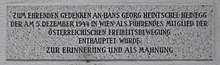

A memorial plaque was attached to his former home at Wohllebengasse 7 in Vienna- Wieden .

Fonts

- Hans Georg Heintschel-Heinegg: Legacy. With a biographical introduction by Rüdiger Engerth . Cross section publishing house, Graz 1947.

literature

- Aurel Billstein: One falls, the others move up ..., documents of resistance and persecution in Krefeld 1933 - 1945. Frankfurt 1973, DNB 740132083 .

- Ulrich Bons: Poems behind walls. In: Anrather Heimatbuch 2000. Willich-Anrath 1999.

- Ulrich Bons: The death of an Austrian abbot in Anrath prison. In: Heimatbuch des Kreis Viersen 2000. Viersen 1999.

- Erich Burghardt : Through historical crises: a life between the 19th and 20th centuries, Böhlau Verlag Vienna, 1998, ISBN 3-20-59879-42

- Ildefons Fux : Hanns Georg Heintschel-Heinegg, theology student, poet, patriot. In: Jan Mikrut (Ed.): Martyrs of Faith . Vol. I, Dom-Verlag, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-85351-159-7 .

- Christine Klusacek: The Austrian freedom movement group Roman Karl Scholz. Vienna 1968.

- Ignaz Christoph Kühmayer: Resurrection. Dom-Verlag, Vienna 1948.

- Helmut Moll (publisher on behalf of the German Bishops' Conference), witnesses for Christ. Das deutsche Martyrologium des 20. Jahrhundert , Paderborn et al. 1999, 7th revised and updated edition 2019, ISBN 978-3-506-78012-6 , Volume I, pp. 861–864.

- Otfried Pustejovsky: Christian resistance against Nazi rule in the Bohemian countries. Lit Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8258-1703-9 .

- Heinrich Zeder: Judas is looking for a brother. Vienna 1947.

- Heintschel from Heinegg, Hanns Georg. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 2, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1959, p. 251.

Web links

- Entry on Heintschel-Heinegg, Hanns Georg in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

Individual evidence

- ^ History of the Kněžice Castle

- ↑ Erich Burghardt : Through historical crises: a life between the 19th and 20th centuries, Böhlau Verlag Vienna, 1998, ISBN 3-20-59879-42

- ↑ Hanns Georg Heintschel-Heinegg was the uncle of Burghardt's wife

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Heintschel-Heinegg, Hanns Georg |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hanns Georg Heintschel from Heinegg |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian resistance fighter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 5, 1919 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kněžice , Czechoslovakia |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 5, 1944 |

| Place of death | Vienna |