Great famine in Ireland

As Great Famine ( English Great Famine or Irish potato famine , Irish An Gorta Mór ) in the story received famine from 1845 to 1849 was the result of several by the then new blight induced crop failure , by the then main food of the population of Ireland , the potato , was destroyed. The consequences of the bad harvests were caused by the laissez-faire ideology dominated by the Whig government under Lord John Russell considerably tightened.

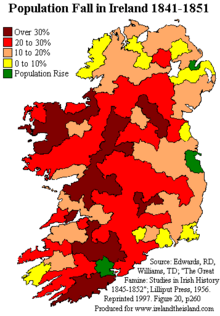

A million people died as a result of the famine, about 12 percent of the Irish population. Two million Irish managed to emigrate .

Causes and history

Ireland had been under English rule since 1541 . Most of the land in Ireland belonged to large English landowners as a result of so-called " plantations ". H. the settlement of immigrants from the neighboring island. Irish farmers worked the land as tenants, growing grain and potatoes, and keeping small numbers of cattle. Grain and animal products were used to pay rents to the great landowners and were brought to England , while potatoes, easy, cheap and quick to grow, were the staple food of the Irish people. Even a small piece of land was enough to feed a large family with potatoes.

Since the Catholic emancipation, beginning in 1778, the Catholic Irish had received the right to own land, but they rarely had the means to buy it.

With 72 percent of the Irish population living on agriculture , lease land became increasingly scarce. A government commission, led by the Earl of Devon , investigating conditions in Ireland found that Ireland needed at least eight acres (about 5 hectares ) of land to survive. However, only seven percent of the leased land was larger than 30 acres, while 45 percent was smaller than five acres. In the poorest province, Connacht in western Ireland, the proportion of such small pieces was as high as 65 percent.

Job opportunities outside of agriculture were virtually non-existent as there was no industry except in Northern Ireland ( Ulster ) . This was received through unilateral customs protection measures by Great Britain. It is true that commissions of inquiry and economic theorists put forward various proposals for promoting Irish economy and industry, for example through land reforms and strengthening the rights of tenants, public construction projects or the construction of a railway network. Neither of these proposals was implemented as it would not have been in line with the UK's economic policy at the time.

The lack of land and jobs was exacerbated by a previous real population explosion .

Development of the population of Ireland:

- 1660: approx. 500,000

- 1760: 1,500,000

- 1801: 4,000,000-5,000,000

- 1821: 7,000,000

- 1841: 8,100,000

The cause of the population growth was the potato cultivation, which made it possible to more or less support a family even on a small piece of land. It was also common to marry very young and have many children.

famine

blight

The disadvantage of the dependence on the potato was that it became susceptible to disease, which is typical for continuous monoculture cultivation. Since the soil could not recover by alternately growing other crops, it was easy for potato-specialized pathogens to spread more and more in the soil and to infect it. Even before 1845 there had been repeated (often locally limited) crop failures and famines in Ireland, for example a famine of comparable magnitude in 1740–1741 . Between 1816 and 1842 there were 14 bad harvests of potatoes. The reason for this series is mainly due to the eruption of the Tambora volcano , which influenced the global climate, so that the year 1816 even went down in history as the year without a summer . The continuous rain destroyed the sandy, airy, dry soil that the potato needs in order to thrive optimally, carried the pathogens everywhere and thus created the ideal framework for the subsequent disaster.

In 1842, a hitherto unknown disease emerged in North America that destroyed almost the entire harvest. This "potato blight " was triggered by the oomycetes (egg fungus) Phytophthora infestans , which causes the tubers to rot. The spores are spread by the wind and thrive particularly well in cold, humid climates. Potato rot does not affect all potato varieties, but only two varieties were grown in Ireland at the time and both were susceptible. Thus the Oomycet found particularly good conditions in Ireland.

From North America the Oomycet spread to Europe . For the summer of 1845, crop failures were forecast in the Netherlands , Belgium and France ; in August of the same year, plant damage was also evident in England. On September 13th, leaf discoloration was first reported in Ireland, suggesting that the harvest there would also be affected. But it was hoped this would only affect a small part. At the harvest time in October, however, it was found that the harvest was almost completely destroyed.

Political reactions

overview

The political reactions were generally very cautious. According to the then prevailing economic-political orthodoxy of laissez-faire , the state should interfere as little as possible in the economy. State interference in the trade and distribution of food was seen as a violation of the laissez-faire principle . Therefore z. For example, a temporary ban on the export of Irish grain and a ban on alcohol distillation from food despite the famine were not considered, although these measures had proven to be very successful in earlier bad harvests. The rejection of these state interventions, which were often practiced in the past, marked a radical change in policy. In addition, the Europe-wide poor harvests between 1846 and 1849 led to an increasing demand for wheat, while many European countries stopped exporting food at the same time in order to prevent famine in their countries. This caused the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland to export more wheat during the famine years than in previous years.

The Irish were greatly exasperated when large quantities of food were being transported from Ireland to England while many people in Ireland were starving. For most of the five year famine, Ireland was a net exporter of food. John Mitchel formulated a common view in 1861:

"The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the Famine."

"The Almighty, certainly, sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine."

Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel

Great Britain's Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel initially took countermeasures in November 1845 by ordering the purchase of corn from the United States worth £ 100,000 without the approval of the Cabinet . The corn was to be sold by a Relief Commission in Ireland, the prices initially corresponded to cost, from 1846 the corn had to be sold to the population at market prices on the instructions of the Relief Commission . However, a large part of the population could not pay these prices; most of the starving Irish had no cash at all. Later were job creation measures introduced, which were also coordinated by the Relief Commission.

In Great Britain, the political controversy over aid measures in favor of Ireland was at times overshadowed by the debate over the abolition of import tariffs on grain, the so-called Corn Laws . These were issued to protect the British and Irish grain industries from competition. On the official justification that these tariffs made the import of food more expensive for Ireland too, Robert Peel argued for the abolition of the Corn Laws. Historians consider this line of argument to be a pretext, as the parliamentary debates at the time show that hardly any MPs assumed that the abolition of the Corn Laws would reduce the Irish famine. Peel's parliamentary speeches also show that Ireland, due to the great dominance of the agricultural sector, would be one of those parts of the country for which the abolition of the Corn Laws would have to be disadvantageous. When an even worse potato harvest was foreseen for 1846, Peel achieved the abolition of the Corn Laws, but lost the support of his party.

Prime Minister John Russell

In June 1846 the ruling Tories were replaced by the Whigs . The new Prime Minister was John Russell , a staunch supporter of the laissez-faire ideology. The Whigs and their supporters feared growing dependence of the Irish on government support rather than widening starvation. In addition, the proponents of Manchester liberalism had won many seats. They advocated a downsizing of the state and a cut in government spending, and the aid to Ireland in particular was a thorn in their side. After the government came to power, the Relief Commission was abolished and it was ordered that job creation measures had to be financed exclusively by the Irish part of the country.

In autumn 1846, not only the potato harvest was affected , but also the wheat and oat harvests due to the unfavorable weather . However, the Irish tenants continued to have to pay the full rent, selling grain and animal products that were exported to England. Allegedly, for every ship that brought food to Ireland, there were several ships in port carrying food. Tenants who could not afford the rent were driven from the house and farm (the houses were often burned down as a punishment) and thus lost all means of livelihood. This happened to tens of thousands; a notorious example of this is the Ballinlass Incident .

Under the English Poor Law , which had also been introduced in Ireland in 1838, there was no direct financial or material support from the government to the starving. Help was after the poor law only in the prison-like workhouses (workhouses) provided, which in turn were daunting set deliberately as possible. The intention behind this was to prevent dependence on government support and instead to rely on the initiative of those affected. In 1847, the Poor Law was amended to require the Irish part of the country to finance the Irish poor houses itself. The rapidly increasing number of those in need pushed the system to its limits. The inmates could not be adequately fed but had to do hard physical labor. In addition, the hygienic conditions were catastrophic and epidemics developed. In March 1847 there was a death rate of 2.4 percent of inmates per week in the workhouses, which rose to 4.3 percent in April 1847.

The government only intervened by organizing job creation measures. Irish merchants and large landowners should bear the cost of these measures . Since these were also almost bankrupt due to the poor harvests , they were neither willing nor able to spend money on this, so that the state had to step in. In addition, due to the hard and long winter of 1846/1847, the costs continued to rise. Whereas 114,600 jobs were placed in October 1846, 570,000 in January 1847 and 734,000 in March of the same year. In total, the state spent £ 10,500,000 on job creation programs during the famine, with most of the money booked as lending to the Irish part of the country. This sum was in stark contrast to the sums spent on other projects. For example, the West Indian slave owners received £ 20,000,000 in compensation for abolishing slavery.

In many cases, the approval process for job creation measures took so long that some of the selected workers were already too emaciated to work at the start of the project:

“Often in passing from district to district I have seen the poor enfeebled laborer, young and old alike, laid down by the side of the bog or road, on which he was employed, too late for kindness to avail, nevertheless, giving his dying blessing to the bestowers of tardy relief. "

“As I moved from district to district, I often saw the exhausted worker, young or old, lying on the edge of the swamp or on the road on which he should have worked. Help came too late for him, but he spoke to you anyway last blessing for those who initiated the belated help. "

The situation worsened in February 1847 when heavy snowfalls made it difficult for the already starved population to survive. Many displaced people then wandered homeless and fell victim to the cold. Even diseases like typhoid were rampant. Ultimately, a large part of the population was no longer physically able to work in the job creation projects and thus earn state support. In the spring of 1847, the job creation programs were terminated because of the high costs. A sharp rise in deaths forced Prime Minister Russell, contrary to his intentions, to set up soup kitchens financed in part by UK government loans and in part by donations from around the world. The Choctaw , a North American Indian people who had suffered the path of tears a few years earlier , also donated money. In August 1847, three million people were being fed by these soup kitchens.

In September 1847 the famine was declared over and state lending to the soup kitchens stopped. The initiative for this came from the head of the Treasury, Sir Charles Trevelyan. He considered the famine to be a direct result of the “omniscient and compassionate care” that, in his opinion , would only prolong the Malthusian catastrophe . The misery continued and in 1848 and 1849 the potato harvests failed again. In 1848 the " Young Ireland " movement under the leadership of William Smith O'Brien and Charles Gavan Duffy tried to fight for Ireland's independence from Great Britain. The poorly organized and poorly equipped uprising was quickly put down.

The end of the famine is usually given in 1849. According to sources, however, in some areas in 1851, bodies of starvation were lying on the roadside. Poverty in Ireland was no more than the long-term consequences of famine.

consequences

Demographic Consequences

In 1841 there were over 8.1 million people in Ireland. It is estimated that these numbers should have been 9 million if it had developed normally. Instead, after the famine, it was 2.5 million fewer - 6,552,000. At least a million of them died of starvation and its aftermath. 1.5 million people tried their luck in Canada , Australia , the USA and the industrial centers of England.

Between 1841 and 1844, an average of 50,000 Irish emigrated per year. After the poor potato harvest in 1845, this number did not initially increase, as most Irish hoped that the next harvest would be better. But when the harvest failed again in 1846, the number of emigrants skyrocketed. Some large landowners promoted and financed the departure of their tenants, considering that it would be cheaper to pay a one-time crossing than to have to pay for the long-term maintenance in a poor house. There were youngsters who committed crimes in order to be deported to convict colonies like Australia, where they would not be free but at least received food.

It is estimated that nearly two million Irishmen left the country between 1845 and 1855. About three quarters of them emigrated to North America, the remaining 25 percent went to Great Britain and Australia.

Diseases and epidemics were widespread on board the poorly equipped emigration ships , which earned them the name coffin ships (" coffin ships "). Most of the Irish immigrants were not welcomed with great pleasure because of the fear that they would bring in epidemics. Many such ships were diverted from the USA to Canada. On the Great Isle in Canada, where almost 10,000 Irish people were buried in 1847 alone, a plaque indicates that many died after landing:

“Thousands of the children of the Gael were lost on this island while fleeing from foreign tyrannical laws and an artificial famine in the years 1847-8. God bless them. God save Ireland! "

“Thousands of Irish children perished on this island while fleeing from foreign, tyrannical laws and an artificial famine in 1847-8. God bless you. God save Ireland! "

Those who survived the crossing belonged to the lowest social class in their new home. Because of their Catholic denomination and their origins, they were confronted with prejudice. In order to survive, they did the hardest and dirty work at very low wages, which earned them the hatred of the ancestral working class, which the Irish became a competition. Irish women worked as servants and in textile factories, the men building railroad lines and canals or mining . Many men were killed in these dangerous activities. As one saying goes, “an Irishman was buried under every railroad tie”. Although, or precisely because, they belonged to the lowest stratum of the population, there was great solidarity among the Irish emigrants. They remembered the old traditions and supported the relatives who had stayed in Ireland. Many Irish-Americans took to the side of the Union in the American Civil War in part 1861-65. They saw it as a preparation for the fight against England.

Even after the famine, emigration from Ireland continued due to the continued poor economic conditions, until around 1900 tens of thousands left the country every year. Ireland's population never reached pre-famine levels. In 1901 the low point was reached with 3,500,000 inhabitants, since then the population of Ireland has increased again. In 2005 the entire island of Ireland had 5,800,000 inhabitants (up from about 8,100,000 before the famine).

Another consequence was the almost complete decline of the Irish (Gaelic) language . This was already in decline before the famine, as in the 18th century English had become the language of the upper class of society, administration and government and economic and social advancement as well as political activities were tied to the English language. In 1841 four million Irish people still spoke Gaelic. Most of them, however, belonged to the lower class of society, most of whom fell victim to the famine. In 1851 only a little less than 25% of the population spoke Gaelic. The Irish-speaking emigrants largely gave up their language and instead let their children learn English in order to save them communication problems.

The famine did not only affect the Irish language. In view of the great hardship, the many dead and emigrants, many old customs, songs and dances were forgotten.

Political Consequences

The social and political conditions that contributed to the catastrophe initially remained unchanged after the famine in the 1850s and 1860s. Historians speculate that the traumatic experiences of the famine weighed so heavily on the Irish population that it largely paralyzed political activism.

In the longer term, however, as a result of the famine, the (also violent) endeavors to change these conditions and for Ireland to become independent from Great Britain grew. The situation was already tense before 1845 - after centuries of British foreign rule - and there had been uprisings again and again; Great Britain's reaction to the famine, however, was perceived by a large part of the population as a harsh and inhumane attitude and thus contributed to an increase in hatred of England. Had a peaceful solution on the negotiating table been conceivable before the famine, violence afterwards appeared to be the legitimate, if not the only means of achieving Irish independence.

The emigrants played a not insignificant role. They had taken their memories of the hardship and hatred of Great Britain, which in their opinion had forced them to emigrate, with them to their new home. A large number of Irish emigrants supported morally and financially newly emerging resistance organizations in Ireland such as the Irish Republican Brotherhood (Fenier) or the Irish National Land League . "[...] it is probably these connections in which the main legacy of the Great Hunger can be seen."

From the 1870s onwards, these organizations and Irish politicians acted with increasing intensity (and in some cases also violently) for a change in social and political conditions and for self-determination and independence for Ireland ( Home Rule ) . In particular, Charles Stewart Parnell , also known as the "uncrowned King of Ireland", stood out as an advocate of the Irish cause. Political pressure on England gave Ireland a seat in the lower house of the British government in Westminster , where Parnell repeatedly cited the famine as an example of the exploitation of Ireland by Great Britain and attributed the death of hundreds of thousands to this as an inevitable consequence.

The tenants, who often lived in dire poverty, also began to organize against the landlords. After the potato harvest was again bad in 1879 and many affected farmers feared another famine , Michael Davitt founded the Irish National Land League together with Parnell , which in the coming decades agitated in the so-called " Land War " for the concerns of the tenants. The Land Acts and the Wyndham Land Purchase Act of 1903 returned Irish peasant ownership to Irish land. Emigration overseas also increased again.

The increasingly violent efforts for independence continued ( Easter Rising , Irish War of Independence ) and finally led to the independence of the Republic of Ireland in 1921, with the exception of the province of Ulster , which to this day has remained largely British and largely Protestant and where the conflict between former (Protestant, originally British ) Conquerors and (Catholic, Irish) conquered continued for a long time.

Cultural debate today

The Great Famine is often seen as a turning point in Irish history and its effects are viewed from different angles (demographics, politics / aspirations for independence / Northern Ireland conflict , culture, Irish emigrants in their new home etc.).

To this day, the Great Famine is part of poems and songs of various kinds, such as the subject of the folk song The Fields of Athenry . The Irish folk punk band The Pogues addressed the wave of emigration caused by the famine including the problematic foothold in the USA in the song Thousands Are Sailing , published in 1988 on the album If I Should Fall from Grace with God . The Irish pagan metal band Primordial released the song The Coffin Ships on their 2005 album The Gathering Wilderness on the same subject . The Irish singer Sinéad O'Connor released the song Famine in 1995 , in which she comments on what happened.

See also

literature

- Essays

- Thomas P. O'Neill: Food problems during the great Irish famine. In: Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland , Vol. 82 (1952), pp. 99-108, ISSN 0035-9106 .

- Thomas P. O'Neill: The scientific infestigation of the failure of the potato crop in Ireland 1845/46 . In: Irish Historical Studies , Vol. 5 (1946), Issue 18, pp. 123-138, ISSN 0021-1214

- Non-fiction

- Anonymous: About agriculture and the condition of the classes practicing agriculture in Ireland and Great Britain. Excerpts from the official investigations which Parliament has made public from 1833 to the present day, Vol. 1: Agriculture in Ireland . Gerold, Vienna 1840

- John R. Butterly and Jack Shepherd: Hunger. The biology and politics of starvation . Dartmouth College PRess, Hanover, NH 2010, ISBN 978-1-58465-926-6 .

- Leslie A. Clarkson and E. Margaret Crawford: Feast And Famine. A History of Food and Nutrition in Ireland 1500-1920 . OUP, Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-19-822751-5 (EA Oxford 2001).

- John Crowley (Ed.): Atlas of the Great Irish Famine . University Press, Cork 2012, ISBN 978-1-85918-479-0 .

- Robert D. Edwards, Thomas D. Williams: The Great Famine. Studies in Irish History 1845-52 . 2nd edition Lilliput Press, Dublin 1997, ISBN 0-946640-94-7 (EA Dublin 1956)

- Jürgen Elvert: History of Ireland . 4th edition Dtv, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-423-30148-1 (EA Munich 1993).

- Emily Mark Fitzgerald: Commemorating the Irish Famine: Memory and the Monument. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 2013, ISBN 978-1-84631-898-6 .

- Cormac Ó Grada: Black '47 and Beyond. The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy and Memory . University Press, Princeton NJ 1999, ISBN 0-691-07015-6 .

- Cormac Ó Gráda: The Great Irish Famine (New Studies in economic and social history; Vol. 7). CUP, Cambridge 1995, ISBN 0-521-55266-4 (EA Cambridge 1989).

- Cormac Ó Gráda, Richard Paping, and Eric Vanhaute (Eds.): When the Potato failed. Causes and Effects of the “Last” European Subsistence Crisis, 1845-1850 (CORN Publication Series; Vol. 9). Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 2007, ISBN 978-2-503-51985-2 .

- John Kelly: The graves are walking. A history of the Great Irish Famine . Faber & Faber, London 2013, ISBN 978-0-571-28442-9 .

- Donal A. Kerr: A Nation of Beggars? Priests, People, and Politics in Famine Ireland 1846-1852 . 1st edition Clarendon Press, Oxford 1994, ISBN 0-19-820050-1 .

- Christine Kinealy: A Death-Dealing Famine. The Great Hunger in Ireland . Pluto Press, London 1997, ISBN 0-7453-1075-3 .

- Christine Kinealy: This Great Calamity. The Irish famine, 1845-1852 . Gill & Macmillan, Dublin 2006, ISBN 978-0-7171-4011-4 (EA Dublin 1994).

- Francis Stewart Leland Lyons: Ireland since the famine . Fontana Press, London, 10th ed. 1987, ISBN 0-00-686005-2 , pp. 40-46 (first edition 1971).

- John O'Beirne Ranelagh: A short history of Ireland CUP, Cambridge 1994, ISBN 0-521-47548-1 .

- Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey: From the corn laws to free trade. Interests, ideas, and institutions in historical perspective . MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2006, ISBN 0-262-19543-7 .

- Alexander Somerville: Ireland's Great Hunger. Letters and reports from Ireland during the famine of 1847 . Edited by Jörg Rademacher. Unrat, Münster 1996, ISBN 3-928300-42-3

-

Amartya Sen : Development as freedom . OUP, Oxford 11999, ISBN 0-19-829758-0 .

- German translation: Economy for people. Paths to justice and solidarity in the market economy . Dtv, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-423-36264-1 (translated by Christiana Goldmann).

- Vernon, James: Hungry. A modern history. Cambridge 2007.

- Leslie A. Williams: Daniel O'Connell , the British Press and the Irish Famine. Killing Remarks . Ashgate Publ., Aldershot 2003, ISBN 0-7546-0553-1 .

- Cecil Woodham-Smith: The Great Hunger. Ireland 1845-1849 . Penguin Books, London 1991, ISBN 0-14-014515-X .

- Angela Wright: Potato People (Fiction Factory; Vol. 26). Cornelsen Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 978-3-464-08529-5 (adaptation for the 8th school year)

- Fiction

- Jonatha Ceely: Mina . Delacorte Press, New York 2004, ISBN 0-38533-690-X .

- German translation: Mina. Historical novel . Blanvalet, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-442-36102-8 (translated by Elfriede Peschel).

- Ann Moore: Leaving Ireland . Putnam Penguin, New York 2002, ISBN 0-4512-0707-6 .

- German translation: Farewell to Ireland . List, Berlin 2005, ISBN 978-3-471-79489-0 (translated by Franca Fritz and Heinrich Koop).

-

Joseph O'Connor : Star of the sea. Farewell to Old Ireland . Vintage Press, London 2003, ISBN 0-099-46962-6 .

- German translation: The crossing. Novel . S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 2003, ISBN 3-10-054012-3 (translated by Manfred Allié and Gabriele Kempf-Allié).

-

Liam O'Flaherty : Famine . Wolfhound Press, Dublin 2000, ISBN 0-86327-043-3 (EA London 1937)

- German translation: Angry green island . An Irish saga . Diogenes Verlag, Zurich 1987, ISBN 3-257-21330-1 (translated by Herbert Roch; former title: Hungersnot ).

Web links

- Full information on the famine

- Map of the affected areas

- Strokestown Park National Famine Museum, Roscommon, Ireland

- Ireland's Great Hunger Museum, Quinnipiac University, Connecticut

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Jim Donelly; The Irish Famine . On BBC History February 17, 2001.

- ↑ Rudolf von Albertini : Europe in the Age of Nation-States and European World Politics up to the First World War . In: Handbook of European History . tape 6 . Klett, Stuttgart 1973, ISBN 3-8002-1111-4 , p. 275 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Edward J. O'Boyle: Classical Economics and the Great Irish Famine. A study in limits . In: Forum for Social Economics , Vol. 35, (2006) No. 2 ( (PDF; 114 kB) ).

- ↑ a b Christine Kinealy: A Death-Dealing Famine. The Great Hunger in Ireland , p. 61.

- ↑ a b Christine Kinealy: A Death-Dealing Famine. The Great Hunger in Ireland , p. 77.

- ^ John O'Beirne Ranelagh: A Short History of Ireland , p. 115.

- ↑ See also Amartya Sen : Development as Freedom . Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, ISBN 0-19-829758-0 , p. 172.

- ↑ Christine Kinealy: A Death-Dealing Famine. The Great Hunger in Ireland , p. 6.

- ↑ a b John R. Butterly and Jack Shepherd: Hunger , p. 114.

- ↑ Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey: From the Corn Laws to Free Trade , S. 176th

- ↑ Christine Kinealy: A Death-Dealing Famine. The Great Hunger in Ireland , p. 58.

- ^ Leslie A Williams: Daniel O'Connell , the British Press and the Irish Famine , p. 16.

- ↑ Christine Kinealy: A Death-Dealing Famine. The Great Hunger in Ireland , p. 65.

- ^ Cormac Ó Grada: Black '47 and Beyond. The Great Irish Famine , pp. 50-51.

- ↑ Christine Kinealy: A Death-Dealing Famine: The Great Hunger in Ireland , p. 75.

- ^ A b John R. Butterly and Jack Shepherd: Hunger , p. 115.

- ↑ Christine Kinealy: A Death-Dealing Famine. The Great Hunger in Ireland , p. 73.

- ↑ John R. Butterly and Jack Shepherd: Hunger , p. 116.

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of May 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ John R. Butterly and Jack Shepherd: Hunger , p. 117.

- ↑ John R. Butterly and Jack Shepherd: Hunger , p. 119.

- ↑ cf. Patrick Mannion: A Land of Dreams. Ethnicity, Nationalism, and the Irish in Newfoundland , Nova Scotia , and Maine , 1880-1923. McGill Queen's UP, Montreal 2017

- ↑ Volume 2: Agriculture in Great Britain . Gerold, Vienna 1840.