Isabella Beeton

Isabella Mary Beeton (March 14, 1836 in London as Isabella Mayson ; † February 6, 1865 ), commonly known as Mrs. Beeton , was the main author of the book Mrs. Beeton's Book of Household Management , which became a bestseller shortly after its publication and is reprinted in countless editions to this day. Isabella Beeton died in childbed at the age of only 28 . She is considered the most famous and well-known cookbook author in Great Britain . Her name, detached from her person, became a brand name under which books and food are sold and advertised to this day.

Life

childhood and education

Isabella Mary Mayson was born in Marylebone , London in 1836 . Shortly after their birth, the family moved to their father's trading house, a cloth wholesaler at Clement's Court in the City of London . In 1836 the prosperous trading company and its family moved to Milk Street, where Benjamin Mayson had acquired a prestigious building. Benjamin Mayson died in 1840 at the age of only 39. His widow, Elizabeth Mayson, who was only 25 years old, suddenly found herself running a cloth business with four young children. , The oldest of four siblings Isabella, was first to her grandfather, a widowed pastor in Great Orton ( Cumbria , sent). Isabella's mother continued to run the business with little success, as a petition to her father-in-law shows. In 1843 Elizabeth Mayson married the printer Henry Dorling, with whose family the Maysons had long been friends. Henry Dorling had also just become a widower and had four young children.

Henry Dorling was the owner of a printing company and in the years before had been more and more involved in the Epsom Derby , an extremely popular annual horse race, which increasingly attracted the London masses with the rail link established in 1837. Since 1839 he has been running the race as Clerk of the Course (director of the racecourse). In 1845 he was able to acquire the lease of the Grandstand , a classicist grandstand building with galleries, balconies, but also ballrooms, salons and hotel rooms that could accommodate 5,000 spectators.

After the new family with their eight children - Isabella had meanwhile returned to her mother from Great Orton - initially set up in the building of Henry Dorling's print shop in Epsom , the extended family moved to Ormond House a few years later . The proud, white, detached house was built in the form of an ancient temple, the stepfather's printing shop and library. Charles Dickens reported in 1851: “A railway takes us, in less than an hour, from London Bridge to the capital of the racing world, close to the abode of the Great Man who is - need we add! - the Clerk of Epsom Course. It is necessarily one of the best houses in the place, being - honor to literature - a flourishing bookseller's shop " . (A train takes us from London Bridge to the capital of the world of horse racing in less than an hour , straight to the residence of the Big Man who, must it be said, is the director of the Epsom Racecourse. It is, of course, one of the best houses of the place, and - honor of literature - a flourishing bookstore.) Since the house was too small for the increasingly large number of children - by 1859 it grew to a total of 21 children - some of the children, including Isabella, lived temporarily in the outside area Grandstand largely unused during the racing season .

Isabella Mayson's schooling is known to have attended a small boarding school in London, which, like many such institutions of the Victorian era, had only a few students and was run by two single elderly women. From 1851 to 1854 Isabella Mayson lived in Heidelberg in the school of Charlotte and Auguste Heidel, a boarding school that had specialized in English pupils. In addition to German and French, the schedule also included “logical thinking”, natural history and mathematics, as well as history and geography. There were also calligraphy and handicrafts.

Marriage to Samuel Beeton

On her return to her stepfather's house in Epsom, Isabella Mayson, who was now officially available for the marriage market, took piano lessons from Julius Benedict in London and - to the amazement of her family - baking lessons from a local baker. It is believed that Isabella Mayson was introduced to the publisher of books and popular magazines, Samuel Orchard Beeton , while in London . The Mayson, Beeton, and Dorling families had been in contact for a long time. All three families sent their daughters to the Heidelsche Institute in Heidelberg, further contacts arose through the horse races in Epsom. However, it is not known when and under what circumstances Samuel Beeton and Isabella Mayson met. The formal engagement in the summer of 1855 was followed by a year of intensive correspondence before the wedding. These letters have been preserved and already suggest the clear, direct and strong-willed language of the later author.

Isabella Mayson and Samuel Beeton were married on July 10, 1856 at St. Martin's Parish Church, Epsom. The subsequent breakfast in the grandstand with the guests can be arranged using the Bill of Fare for a July wedding, ball, or christening, for 70 or 80 guests (menu sequence for a wedding, a ball or a christening in July with 70 or 80 guests) , which Isabella Beeton later lists in the Book of Household Management , as an opulent celebration with exquisite dishes. After their honeymoon through France and Germany, the Beeton couple moved into Chandos Villa Number 2 in August 1856, a newly built, spacious semi-detached house in Pinner , a north-western suburb of London in the county of Middlesex (Pinner has been part of Greater London since 1965 ). The house consisted of five bedrooms and was equipped with running water and oil heating. As was customary at the time, Samuel Beeton had the house furnished before the wedding. From Isabella's letters during the engagement period, however, it emerges that she did have some influence on the design of the rooms and had precise ideas about materials and functions, which she conveyed directly and unequivocally to her fiancé. Contrary to what Isabella Beeton suggested in her books, she herself probably never had more than two domestic servants.

Journalistic Beginnings and the Book of Household Management

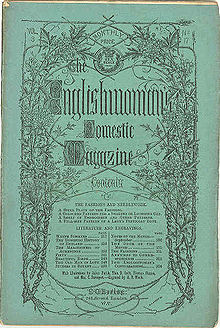

Isabella Beeton became pregnant shortly after the wedding. During this time she began writing articles on fashion, cooking, and housekeeping for her husband's publisher The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine . Her first contributions appeared in March 1857, just a few weeks before the birth of their first child. It is unclear what prompted Isabella Beeton to be a journalist at the time. She had already translated some fictional texts from French and German for the magazine, and the letters she received from the engagement time prove her linguistic dexterity. However, it was probably more economic reasons - the magazine, founded in 1852, was experiencing its first doldrums and some of the columns such as Cooking, Pickling and Preserving or Things Worth Knowing had been orphaned for months and were missing probably competent female journalists.

Isabella Beeton's first child, Samuel Orchart, died at the age of three months. From today's perspective, there is much to suggest that the child suffered from prenatal syphilis , which Samuel Beeton presumably infected his wife with. The fact that she suffered several miscarriages before the birth of her second child in 1859 supports this thesis.

Isabella Beeton had started to write articles for the Cooking, Pickling and Preserving section on a regular basis . Soon after, the Beetons seem to have been planning to put together a larger cookbook, as suggested by a July 1857 letter from Henrietta English, a friend of the Dorling family, who had asked the Beetons for advice on this matter. Henrietta English recommends Therefore my advice would be compile a book from receipts from a Variety of the Best Books published on Cookery and Heaven knows there is a great variety for you to choose from (My advice is therefore: Write a book together with recipes a selection of the best books on cooking, there are heaven knows a great number to choose from). In fact, Isabella Beeton seems to have followed this advice: Comparisons of the Book of Household Management with other, earlier cookbooks show that a large part of Beeton's recipes, even entire passages of text, come from other books. So her role was more that of an editor. The content did not arise from the rich experience of a single cook and author, but from the meticulous research and skillful collage of a 23-year-old journalist with no significant household or cooking experience. The only vaguely developed copyright law in England at the time did not stand in the way of adopting foreign texts for a new work. The book should probably appear in a series with other overview works and lexicons (such as Beeton's Dictionary of Universal Information or Beeton's Book of Birds ) that Samuel Beeton was just publishing. Nevertheless, Mrs Beeton was considered an innovative original author in England for a long time - a misjudgment that was only exposed as such at the end of the 20th century and that changed Isabella Beeton's image permanently.

The first part of the Book of Household Management appeared in November 1859, five months after the birth of the second child (again Samuel Orchart), and comprised 48 pages. Samuel Beeton advertised the series heavily in Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine , where he initially announced 14 to 18 partial deliveries. The decision to publish 24 parts does not seem to have been made until 1861 - as a result, Isabella Beeton was still researching the last parts while a large part of the book was already published.

Work at the SO Beeton publishing house

With the relaunch of Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine , which appeared in a new format and with a more elaborate design from May 1860, Isabella Beeton was the publisher alongside her husband. It was not just a sonorous title, but a demanding job that Isabella Beeton resolutely tackled. She no longer wrote from home, but accompanied Samuel Beeton daily to the London office of SO Beeton, who was currently enjoying great sales with the household book and Beeton's Dictionary of Universal Information , which was also published in partial deliveries. Both magazines published by the publisher were revised at this time and geared towards a more demanding market.

Isabella Beeton now took over responsibility for larger parts of the women's magazine, which at that time had a circulation of around 60,000 copies a month. Her main task was initially to transform the rather bland section Practical Dress Instructor into a fashion presentation based on the latest Parisian fashion, which should convince the newly targeted audience with style and luxury. The Beetons therefore contacted the editors of Le Moniteur de la Mode in Paris. Le Moniteur shone with exquisite color charts with the latest fashions and the accompanying paper pattern sheets. In the spring of 1860, the Beetons traveled to Paris and managed to negotiate the import of fashion drawings and patterns from the Moniteur for Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine . A diary that Isabella Beeton kept during her trip to Paris tells of meticulously planned and filled days, of negotiations and calculations. It becomes clear that this was a pure business trip in which Isabella Beeton took part as an equal partner.

Instead of the cooking column, recipes and menu suggestions that the beetons took from the household book were only occasionally published. With the new section The Fashions - Expressly designed and prepared for the Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine , the magazine transformed into a fashion magazine that appeared as a supplement in two editions, with or without paper pattern sheets. In addition to the Paris color plates, Isabella reported in detail on the latest Parisian fashions and her critical observations on London ladies. The paper patterns were an absolute novelty in England at the time and were very popular with readers.

If you opted for the cheap version without a pattern, you could also order the sheets of paper individually, an additional service consisted of delivering the patterns adapted to the dimensions of the reader and already cut out. This mail order business was transferred to the Beetons' business partner, Charles Weldon, in the 1890s, under whose name the patterns were offered until the 1950s.

Isabella Beeton's final years

In the autumn of 1861 the Beetons launched another women's magazine called Queen , which, later renamed Harpers & Queen , has been in existence since 2005 as Harper's Bazaar UK . The bound edition of the housekeeping book appeared at the same time. However, Samuel Beeton had to sell Queen after only six months for financial reasons, and legal disputes in connection with the handover ensued. Around the same time, the Beetons moved from the villa in Pinner back to London, where they lived above the offices of the publisher - this, too, an indication of their financially tense situation. Over the next few years, Samuel Beeton remained embroiled in new legal disputes. After the move, the condition of the second child, Samuel Orchart, also began to deteriorate; he finally died at the age of three and a half on New Year's Eve in 1862. Here, too, there are indications of the child's syphilis infection on the death certificate.

Shortly afterwards, Isabella Beeton was pregnant again, and her third child, Orchart, was born on December 2, 1863. In 1863 an abridged version of the Book of Household Management appeared , which made Isabella Beeton's work affordable for all classes. The sales of the books increased. In 1864, shortly after the birth of their third child, the Beetons moved to the London suburb of Greenhithe , Kent , where they rented a farmhouse called Mount Pleasant . In 1863 and 1864 the Beetons traveled several times to Paris and also to Germany, where they visited local attractions as well as business partners of the publishing house in Berlin and Dresden. The couple's close connection in their work for the publisher is evident in the last received letter from Samuel Beeton to his wife, in which he writes about the latest magazine project Young Englishwoman : “I have asked Sidney to get Young to write his notions on paper of what the Y E'woman shd be, irrespectively of mine, and if Y is there tomorrow, as I think he will be, ask Sidney to let you see him, and you can tell him what you think. " (Ich haben Sidney asked to get Young to put his ideas about Young Englishwoman on paper, completely unaffected by mine, and if Young is here tomorrow, which I assume, ask Sidney to meet him and then you can tell him what you think about it.)

Young Englishwoman appeared shortly afterwards in 1864 and remained in the market until the late 19th century. In the same year Isabella Beeton, who was pregnant again, worked out another abridged and formally revised version of her housekeeping book, which appeared in 1865. According to legend, she edited the galley proofs of this cookbook while she was still in labor. Isabella Beeton's fourth child, Mayson Moss, was born on January 29, 1865.

Isabella Beeton died of puerperal fever a week after giving birth to her fourth child . She is buried under a simple tombstone in West Norwood Cemetery . Her husband first tried to prevent her death from being known in order to maintain the "Mrs. Beeton" brand. Accordingly, further editions appeared after her death, the preface of which suggested that she was still alive.

Myra Browne

Myra Browne, who also lived in Greenhithe with her husband Charles, amazingly took her position after Isabella Beeton's death - both as the mother of the two surviving children and as a journalist at SOBeeton, where she is Isabella's position as editor of women's magazines took over, later also realized other projects of his own. Myra Browne ended up living in Samuel Beeton's household with her husband. For the two sons she was Mama , both thought they were long for her birth mother. At a relatively old age she also had her own child, Meredith Browne, although it is unclear whether Samuel Beeton was his biological father. After Samuel Beeton's death in 1877, she took on legal care for Orchart and Mayson Beeton. However, the exact nature of Myra Browne and Samuel Beeton's relationship remains unclear even in retrospect.

Works

The Book of Household Management

Origin of the book

Between 1859 and 1861 Isabella Beeton wrote 24 partial deliveries of a cookery and housekeeping book. These were later published in a volume called The Book of Household Management Comprising information for the Mistress, Housekeeper, Cook, Kitchen-Maid, Butler, Footman, Coachman, Valet, Upper and Under House-Maids, Lady's-Maid, Maid-of -all-Work, Laundry-Maid, Nurse and Nurse-Maid, Monthly Wet and Sick Nurses, etc. etc. - also Sanitary, Medical, & Legal Memoranda: with a History of the Origin, Properties, and Uses of all Things Connected with Home Life and Comfort , which appeared in October 1861.

This book, later known as Mrs. Beeton's Book of Household Management , was a comprehensive guide to running a Victorian household. The foreword begins with: “I must frankly own, that if I had known, beforehand, that this book would have cost me the labor which it has, I should never have been courageous enough to commence it. What moved me, in the first instance, to attempt a work like this, was the discomfort and suffering which I had seen brought upon men and women by household mismanagement. I have always thought that there is no more fruitful source of family discontent than a housewife's badly-cooked dinners and untidy ways. "

("I have to admit that if I had suspected that this book would cost me the effort it actually required, I would never have dared even start. What drove me above all, such a work The inconvenience and suffering that I have witnessed caused by poor housekeeping for men and women has been the inconvenience and suffering that I have always felt that there is no more fertile source of family discontent than bad Cooked dinners and poor housewife cleanliness. ")

The book is aimed at the rising middle class, for whom it should be a reliable source of information and advice. With 60,000 copies sold in the year of publication, the book immediately became a bestseller and was reprinted millions of times within a few years (two million copies sold in 1868). It can serve as a model for many other cookery and housekeeping books of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Isabella Beeton's encyclopedic concept

The table of contents names 44 chapters, initially on general housekeeping (The Mistress, The Housekeeper, Arrangement and Economy of the Kitchen, Introduction to Cookery) , followed by the detailed recipe section, in which general considerations of certain food groups and suitable recipes alternate (General Directions for Making Soups, Recipes, The Natural History of Fishes, Recipes, ...) . After soups, fish, sauces, all kinds of meat, vegetables, pudding, creams, preserves, milk and eggs, baked goods, drinks and health food have been treated in this way, the book ends with further advice for the housewife (Dinners and Dining, Domestic Servants, The Rearing and Management of Children and Diseases of Infancy and Childhood, The Doctor, Legal Memoranda) .

From today's perspective, the book, which was reappeared as a facsimile in 2000, offers a charming and historically significant insight into housekeeping in the Victorian era. Mrs Beeton has become a British icon. The much-cited bonmots ascribed to her, such as “first catch your hare” , are usually not from Isabella Beeton, but from older sources, but her book today is associated with Victorian extravagance and the rural lifestyle of the past Times. In fact, its readership was less of a bourgeoisie or aristocratic, but to be found among the new rising middle class, who received information from Mrs Beeton on pre-produced foods, international recipes and modern decoration ideas.

Isabella Beeton's almost encyclopedic approach can be seen, for example, in the third chapter, Arrangement and Economy of the Kitchen : After a rather philosophical introduction, the author first briefly discusses the kitchens of the Middle Ages, the model of which she identifies as the kitchens of the Romans. She then takes this as an opportunity to illustrate the origin of the function and design of various kitchen utensils , starting with the golden age of Greek mythology, through Homer to finds from Herculaneum . This historical outline takes up four of a total of 13 pages in this chapter. Inferring that because of their functional shape, kitchen appliances still look essentially the same today as they did with the Romans, Isabella Beeton restricts herself to the description of modern materials and their care, as well as the reprint of an inventory list of a household goods store. Overall, it gets along with three sides for modern kitchen appliances and dishes. Another four pages of the chapter is a detailed listing of the different foods, sorted according to their seasonal availability. The other two pages are dedicated to suitable storage conditions for the various foods.

The combination of practical advice with historical backgrounds and discussions of scientific contexts, often attached to a quotation from a literary or philosophical work, are typical for the design of the book. This expresses both the tendency towards scientific management in the 19th century as well as Isabella Beeton's personal education and her comprehensive claim to bundle existing knowledge. The concept was also explicitly advertised: in an advertisement for the book in Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine it says: " Thus if in an recipe for a Christmas plum-pudding, are named the various ingredients (...) BEETON'S BOOK OF HOUSEHOLD MANAGEMENT will give ample information on questions such as these: Where are Raisins grown, and how are they dried? (…) What enters into the manufacture of Brandy, and what are the names of the principal places it comes from? - do we distil any in this country? ... "(If different ingredients are mentioned in a recipe for Christmas Plum-Pudding (...) BEETON'S BOOK OF HOUSEHOLD MANAGEMENT will provide broad information on such questions as: Where are raisins grown and how are they dried? (...) What is brandy made of and where is it mainly made? Do we make brandy in this country? ...).

The 1112 pages of the book contain 2751 references, including over 900 recipes. Most of the recipes were illustrated with colored engravings. It was Isabella Beeton's idea to list the ingredients at the beginning of the recipe. She was also the first to think about systematically specifying the cooking times. In contrast to earlier cookbooks, it also precisely defined the quantities. This made it possible for laypeople to cook more complex recipes according to the recipe. It was one of the first English cookbooks to contain recipes in the format that is still used today.

A typical recipe from the Vegetables chapter :

| FRIED CUCUMBERS 1113. INGREDIENTS. - 2 or 3 cucumbers, pepper and salt to taste, flour, oil or butter. (FRIED CUCUMBERS |

Sources for the Book of Household Management

" The case for the prosecution […] is that Mrs Beeton was a plagiarist who copied down other people's recipes and passed them off as her own […]. Behind the authoritative, all-knowing voice was a simply frightened girl with scissors and paste "writes Kathryn Hughes in her biography about Isabella Beeton. ("For the purposes of the indictment (...) Mrs. Beeton was a plagiarist who copied other people's recipes and sold them as her own (...). Behind the strong, omniscient voice there was only a frightened girl with scissors and glue".)

Elizabeth David was the first to point out in the 1960s that Isabella Beeton was more of a journalist than a cook, who, according to David, had mainly used Eliza Acton's book Modern Cookery for Private Families . Hughes emphasizes that hardly a sentence in Isabella Beeton's cookbook is actually the author's own original creation. Their merit lies rather in having compiled information from a large number of older cookbooks and in structuring it in accordance with their encyclopedic concept. It can be proven that she used recipes, hints and background information not only from Eliza Acton's book, but also from the books of Antoine Carême , cook at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton and in the household of the Prince of Wales, by Louis Eustache Ude , cook of the Duke of York, by Charles Elmé Francatelli , Maître d'hôtel at Queen Victoria and from the work Simpson's Cookery , written by the chef of the Marquis of Buckingham, often verbatim, partly with references to the original authors, partly without comment. Whole paragraphs come from the panthropeon of Alexis Benoît Soyer , the celebrated chef of the Reform Club. Further sources were the cookbooks by Hannah Glasse, Elizabeth Raffald and Maria Rundell as well as The Cooks Oracle by William Kitchiner and Thomas Webster's Enxyclopedia of Domestic Economy , from which she adopted the chapter Arrangement of the Kitchen almost unchanged, including the quotations from Count Rumford , who was friends with Webster.

The Englishwoman's Cookery Book

After the Book of Household Management , The Englishwoman's Cookery Book appeared in 1863 . This book was intended as an inexpensive alternative to the extensive Book of Household Management and essentially only contained its recipe section. It was less lavishly equipped, so the price of 1 shilling was emblazoned in large letters on the red cover .

Mrs. Beeton's Dictionary of Every-Day Cookery

In 1865 another abridged version appeared as Mrs. Beeton's Dictionary of Every-Day Cookery , which was limited to a collection of recipes and advice for preparation and food processing, at the price of 3 shillings 6 pence . It stood in the middle between the inexpensive 1-shilling edition and the more extensive, more elaborately designed and thus considerably more expensive main work. In the publisher's foreword it says:

"No pains have been thought too great to make little things clearly understood. Trifles constitute perfection. It is just the knowledge or ignorance of little things that usually makes the difference between the success of the careful and experienced housewife or servant, and the failure of her who is careless and inexperienced "

("No effort has been spared to make even the little things easy to understand. The little things make perfection. It is precisely the knowledge or the ignoring of the little things that usually makes the difference between the success of the careful and experienced housewife or servant and that Failure of those who are carefree and inexperienced. ")

This last book, conceived by Isabella Beeton herself, was made in Mount Pleasant, the Beetons' country house in Greenhithe. According to her great-niece and biographer Nancy Spain, she is said to have worked on corrections for this tape while she was in labor before the birth of her last child. The book should fill a gap in the market to the more expensive Book of Household Management and the inexpensive Englishwoman's Cookery book. The dictionary , which was published as the first work in a series called Beeton's All About It , is characterized in particular by a table of contents, no longer thematic, but alphabetical, which made it easy to find the individual dishes and made it easier to look up.

Beeton's Book of Needlework

In 1870, after her death, Beeton's Book of Needlework was published , an extensive representation of various handicraft techniques such as tatting , knitting , crocheting , embroidery . The preface by Samuel Butler explicitly states that in the band and the brand new "Point Lace" technique ( needle tip will be described). The work, based on plans by the late Mrs. Beeton (late Mrs. Beeton), was continued and completed by a skilled hand. Interestingly, Isabella Beeton's death was freely admitted here, while later editions of the Book of Household Management sought to hide this fact. Like all later editions, the book was published by Ward, Lock and Tyler , who had bought SO Beeton in 1865.

reception

In 1932 Isabella Beeton's portrait, a hand-colored photograph, was included in the National Portrait Gallery in London. This was the first photograph in the National Portrait Gallery to be admitted there only after a controversial discussion; it is one of only two surviving photographs of the adult Isabella Beeton. At that time, the Book of Household Management was part of the basic equipment of an English household - but Mrs. Beeton was generally considered to be an invented figure at the time. Little was known about her life after Isabella Beeton's death due to her husband's trademark protection policy. Lytton Strachey , who had planned a biography, soon gave up this project due to a lack of usable material. The exhibited portrait therefore generated considerable public interest, it was reproduced many times and achieved enormous popularity.

Until his death in 1947, Mayson Beeton, the son after whose birth Isabella Beeton died, tried to keep the public memory of his parents alive and to correct it: In his opinion, the role of Samuel Beeton as a publisher was given far too little appreciation. At first he planned to write a biography himself, commissioned the lawyer and writer Harford Montgomery Hyde to do research as a co-author, but then handed the collected material over to Nancy Spain, a great-niece of Isabella Beeton. Nancy Spain's biography, which was rather imprecise in many details, appeared in 1948 and did not necessarily portray the Beetons' marriage as a model. Another biography followed in 1951, written by Montgomery Hyde, who had meanwhile returned from the war, which, as intended by Mayson Beeton, emphasized the role of the husband. Harford Montgomery Hyde's work was preceded by a 1936 foreword by Mayson Beeton.

It was not until 1977 that another biography appeared, written by the journalist Sarah Freeman, which, however, was considerably restricted in the selection of the material used by the heirs of the Mayson Beeton estate, concerned about the honor of the family name. The preface to this book was written by Montgomery Hyde.

After the death of Isabella Beeton's last descendant, Rodney Levick, in 1999, the estate was scattered through auction sales, but was first accessible without the family's controlling influence, so that the author of the fourth biography, Kathryn Hughes, published in 2005, is now was able to evaluate all letters and documents.

Since the 1990s, Isabella Beeton's life has also been used as material for musicals, radio plays and plays. She is understood as a symbol of the Victorian era. In February 2007 the BBC aired a television film about Isabella Beeton based on the biography of Hughes.

expenditure

First editions

- The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, 1852-77, ed. 1852–56 by Samuel Beeton, 1856–60 by Samuel and Isabella Beeton, 32 pages, published monthly, circulation 5,000 (1852) -50,000 (1857).

- Beeton's Book of Household Management , 24 monthly parts, London: SO Beeton, 1859–1861.

- Beeton's Book of Household Management , hardcover, London: SO Beeton, 1861.

- The Englishwoman's Cookery Book , London: SO Beeton, 1863.

- Mrs Beeton's Dictionary of Every-Day Cookery , 1865.

Facsimile editions

- Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management. Facsimile edition of the 1861 original edition , Cassell & Co, 2000. ISBN 0-304-35726-X .

- Mrs Beeton's Cookery Book - Diamond Jubilee Edition . Reprint of the 1897 edition on the occasion of the 60th jubilee of Queen Victoria , Impala, 2006.

- Everyday Cookery and Housekeeping Book , Bracken Books, 1984.

- Beeton's Book of Needlework. Facsimile edition , London: Chancellor Press, 1986.

Abridged or partial reprints

In addition, there are numerous abridged editions, as well as reprints in extracts that take up recipes on specific topics, as well as completely redesigned books that only marginally refer to Beeton's recipes, but mention "Mrs Beeton" in the title line, as a seal of approval or for marketing reasons. After Isabella Beeton's death and the end of SO Beeton, the Book of Household Management and the editions derived from it were published by Ward, Lock and Cassell in London, e.g. 1870 Beeton's Book of Needlework , 1871 Beeton's Book of the Laundry: or, The Art of Washing, Bleaching and Cleansing , 1873 Beeton's Book of Cottage Management , 1881 Ward and Lock's Home Book: A Domestic Cyclopedia, being a companion volume to “Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management” , 1908 Mrs Beeton's Penny Cookery Book , 1910 Mrs Beeton's Sixpenny Cookery , 1924 Mrs Beeton's Jam-making (…) , 1973 Mrs Beeton's Favorite Party Dishes , 1991 A Gift from Mrs Beeton: Edible Delights , 1994 Mrs Beeton's Healthy Eating and 2004 Essential Beeton: Recipes and Tips From The Original Domestic Goddess , just to name a few to name a small fraction of the titles published to date.

literature

- Susan Watkin: Know Your Onions or Mrs Beeton's Hinterland . Lulu Press, 2006 (recipes and household advice from sources 1820–1860 that may have inspired Mrs. Beeton's work).

- Kathryn Hughes: The Short Life and Long Times of Mrs Beeton , 2005, ISBN 1-84115-373-7 (comprehensive biography with extensive bibliography, catalog raisonné and directory of primary sources).

- Margaret Beetham: A Magazine of Her Own? Domesticity and Desire in the Woman's Magazine, 1800-1914 . London 1996 (Part II discusses in detail the magazines published by the Beetons).

- Michael Hurd: Mrs Beeton's Book, a Music-Hall Guide to Victorian Living , London, 1984.

- Sarah Freeman: Isabella and Sam: The Story of Mrs Beeton . Victor Gollancz, London 1977 (biography).

- Elizabeth David: Isabella Beeton and Her Book . In: Wine and Food , Spring 1961.

- H. Montgomery Hyde: Mr. and Mrs. Beeton . George S. Harrap & Co, London 1951 (second biography, with a foreword by Mayson Beeton).

- Nancy Spain: Mrs. Beeton and her husband by her grand niece . Collins, London 1948. Later: Beeton Story (1956). (First biography written by Isabella Beeton's great niece).

Dramatic adaptations

- The Secret Life of Mrs Beeton , BBC TV movie, 2006.

- Tony Coult: Isabella - The Real Mrs Beeton , radio play, London 2001.

- Ron Aldridge: Me and Mrs Beeton , drama, London 2000.

Web links

- Book of Household Management , based on the 1861 edition

- Beeton's Book of Needlework

- Google Books scan of the Book of Household Management , 1861 edition

- Google Books Scan of the Book of Household Management , edition from 1863 (copy of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, unfortunately poor scan quality including fingernails of the Google employees)

- Guardian article on allegations of plagiarism

- Science in the 19th century periodical . Article on Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine

- The Secret Life of Mrs Beeton . BBC TV film

- Victorian Britain: The Cookery Book as Source Material (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ 127,500 visitors are reported for 1843 (Hughes, p. 43)

- ^ Charles Dickens in Household Worlds , 1851, cited above. after Hughes, 54

- ↑ Assessment by Kathryn Hughes, who reports large parts of the correspondence

- ↑ Hughes, p. 181ff.

- ^ Hughes, p. 190.

- ↑ Quoted from Hughes, p. 317.

- ^ Beginning of the foreword to Book of Household Management

- ↑ oup.co.uk

- ^ Hughes, p. 203.

- ^ Hughes, pp. 188ff, 205

- ^ Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, p. 569.

- ^ Hughes, p. 198.

- ↑ Hughes, pp. 198-220

- ^ Foreword to Beeton's Book of Needlework , 1870.

- ↑ Hughes, S. 384F.

- ↑ Hughes, p. 3.4.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Beeton, Isabella |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Beeton, Mrs .; Mayson, Isabella Mary (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English cookbook author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 14, 1836 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 6, 1865 |