Jebel Khalid

Coordinates: 36 ° 21 ′ 33 ″ N , 38 ° 10 ′ 27 ″ E

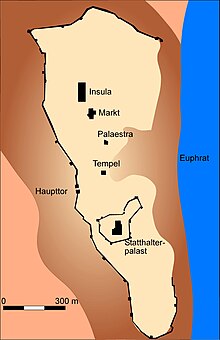

Jebel Khalid ( Arabic جبل خالد, DMG Ǧabal Ḫālid ) is an excavation site on a rocky ridge on the west bank of the Euphrates in present-day Syria . Since the ancient name of the settlement found here is uncertain, the excavation site was named after the rock ridge. Here parts of a Seleucid city could be exposed, the remains of which are spread over an area of about 50 hectares. The settlement was founded in the early 3rd century BC. BC, probably by Seleukos I Nikator , who apparently stationed a garrison here in order to better control the Euphrates. It is located about 50 km south of Zeugma and southeast of Hierapolis. The city stretched along the Euphrates on an elevated plain. The walled urban area is about 1200 m long and 200 to 300 m wide. In the southern part there is a hill with the acropolis . Here the remains of a governor's palace came to light. The excavations also covered a temple, a palaestra , parts of a residential area, parts of the city wall (2.7 km long) and parts of the cemeteries. The population was estimated at 5,000. The reasons for the end of the city are unclear, but could be related to the general end of Seleucid rule and the withdrawal of the garrison. After that people lived only sporadically in the city area.

After site inspections in 1984, excavations were carried out by an Australian team from 1986 to 2010.

geography

Jebel Khalid is on the west side of the Euphrates. To the north of the ruins is the village of Khirbet Khalid and on the opposite side of the river is the village of Rumeilah. The nearest major modern city is Manbij (ancient Hierapolis) 30 km to the northwest. The Jebel Khalid rock ridge, after which the excavation site was named, is covered by an approximately 50 cm thick limestone ceiling, which is mixed with numerous pebble inclusions. Underneath there is a layer of limestone, in which it is quite easy to dig caves or graves. The rock ridge was used when the city was built and later as a quarry. The ridge is 427 m above sea level and at the highest point about 130 m above the Euphrates. The surface of the ridge is rough and is criss-crossed by erosion channels. The region's climate is semi-arid with 250 mm rainfall per year. In spring, the landscape is covered with low bushes and flowers.

History and residents

After the Battle of Ipsos in 301 BC. The empire of Alexander the Great was divided into several smaller Diadochic empires . The former general Seleukos I Nicator secured the east of the empire and thus an area that stretched from the Mediterranean to India . As king, Seleukos I tried to consolidate his domain and founded various cities in strategically important places. On the Euphrates, these included Apamea across from Zeugma in the north and Dura Europos in the south. In contrast, the founding date of other places on the Euphrates, such as Djazla, Nheyle or Siffin, is often uncertain. But these new foundations also seem to have served the purpose of securing the Euphrates. The founding of Jebel Khalid must also be seen in this context. Although the oldest coins found on site were minted under Seleucus I, his successor Antiochus I , who further consolidated the new empire, cannot be ruled out as the founder. The place was heavily fortified. Of the 50 hectares that enclosed the wall, about 30 hectares were built over. It has been suggested that Katoikia were settled here. These were semi-retired soldiers who could be mobilized in times of crisis.

It is not certain whether there was a previous settlement. Various finds indicate that people sporadically lived here before. A few ceramic finds date from the Neo-Assyrian period to the Achaemenian period . Many ceramic forms from the pre-Hellenistic period are still documented in the Hellenistic city. It can be assumed that when the town was founded, numerous residents from the area also moved to the new town. The finds are very strongly influenced by Hellenism, but there are also numerous Asian elements. So have z. B. the floor plans of the houses hardly any direct parallels in the Greek world. The governor's palace appears to follow Hellenistic models, but it also has features that are better documented in Mesopotamian palaces. Most of the written records from the city are Greek inscriptions. These are mostly incisions and inscriptions on ceramic shards and stucco, so-called Dipinti . But there are also isolated Aramaic examples. Although it is believed that a garrison was stationed here, no barracks for soldiers have yet been found.

Little is known about the history of the place. Longer inscriptions, such as consecration stones , have not yet been found. The city flourished especially in the third and early second centuries BC. There is evidence of local pottery and terracotta production, and textiles and metal were used. Olives and grapes have been grown in the area. The large, partly well-equipped houses prove the prosperity of at least some citizens. The second century BC BC saw the advance of the Parthians in Mesopotamia, with which a longer period of peace in this region came to an end. In the north was 163 BC. The Commagene under Ptolemy independent of the Seleucid Empire. Jebel Khalid regained importance as a military base, as the landscape had become a border region. During this time, many changes to the houses can be observed and the excavators wonder whether more residents were moved to the city to strengthen the garrison.

The end of the city

On the basis of the coins, but also other datable finds, it can be assumed that the city was around 70 BC. Was abandoned. During this time the Seleucid Empire was in a phase of dissolution. The excavations showed that in the last 20 years before the city was abandoned, many large houses, but also the Acropolis, were divided into smaller units. The excavators wonder whether the city took in refugees from Mesopotamia who were fleeing the advancing Parthians. Around 74/73 BC Chr. Was Tigranes II. Of Armenia Antioch, taking the capital of the Seleucid Empire. This is also roughly the time when Jebel Khalid was abandoned. It remains unknown whether the garrison in town simply disbanded due to the lack of payments or whether it was withdrawn. Jebel Khalid does not seem to have developed an economic basis, so that when the soldiers withdrew, other residents also moved away. There are signs that the city has been systematically abandoned. The ruins were subsequently used as a quarry, as shown by isolated, mainly Roman coins. Only the temple seems to have been in operation for about 100 years. In Byzantine times, there was a small military camp and a monastery here for a short time. Remains of monk cells, communal rooms and a church were found within an area that served as a quarry in the Hellenistic period.

Ancient name

Two localities that are mentioned in ancient sources come into question as the name of the place. The Byzantine writer Stephanos of Byzantium names a place on the Euphrates called Amphipolis, which the Syrians call Tourmeda and which was founded by Seleucus I. The same author names another place that also comes into question, called Nikatoris, which was also a founding of Seleucus I. But it is also conceivable that the city had a different name that has not been passed down or has not yet been correctly assigned.

buildings

temple

One of the buildings excavated so far is a Greek temple. It is an amphiprostylos building, with columns on the front and back, but not on the sides. The temple stood about 200 m north of the Acropolis and 100 m east of the capital gate. It was therefore likely to be clearly visible from all major points in the city. On the eastern side, the temple was directly on the steep slope to the Euphrates. The floor plan, including the two porticos, was about 17 × 13 m, and inside it had three cellae . The columns belong to the Doric order , but were apparently not fluted . They were about four feet high. The temple was comparatively compact in its proportions. There was hardly any architectural decoration, even antefixes were not found, although the excavation area was rich in roof tiles. It is a Greek temple type, but the three Cellae, as they are more attested in Asia, and the proportions seem to indicate that Mesopotamian influences were also effective.

The ceramic finds indicate that the temple was built in the first quarter of the 3rd century BC. There were also remains of statues, but the building was poorly preserved overall. The statues were only available in small fragments. Some marble fragments are clearly from Hellenistic statues that were likely produced elsewhere. Analysis of the stone revealed that a statue was made from Parian marble . As far as can be seen, they were of high artistic quality. Other statues are made from local limestone. Their quality is well below that of those that were imported. Around the temple stood a row of at least 23 altars about one meter high. They are round and fluted. The altars date from the first century BC - from a time when the city was abandoned. Small finds show that the temple was used until the first century AD. Much of the city was uninhabited at the time.

Palaestra

The remains of a palaestra have been partially excavated about 125 m north of the temple . It is a square surrounded by Doric columns with once 28 columns, eight columns on each side; only two sides have been excavated. The finds include objects that one would actually expect to find in a palaestra, including a bone flute and a bronze strigilis . A strigilis is a scraping instrument that was used to scrape sweat and dust from the body after exercise. The area around the palaestra was densely built up, but only a small part was excavated. There was also a bathroom here. After leaving the city, the building served as a quarry.

Governor's Palace

The governor's palace stands on a rocky hill, the Acropolis, and was surrounded by its own 0.7 km long wall. The rock plateau was partially leveled for the construction. There is no evidence of previous buildings. The palace had a peristyle courtyard (about 17.8 × 17.8 m) with 36 columns in a Doric order. There were various rooms around the courtyard. To the north of the peristyle was a hall with a central column and other rooms arranged around it. The hall with the central column was certainly a reception hall. The hall was 7.39 × 11.34 m in size. The main entrance was in the south; the entrance was flanked by two red stucco pilasters in antis . This hall and some other rooms in the palace were stuccoed and painted in the style of the wall . Some floral motifs were found , but no figurative ones. Much of the paintings imitated marble. A bathroom was also found. The building probably had a second floor. There were numerous roof tiles.

Many parts of the building are obviously designed to represent. Hellenistic traditions dominate with the peristyle in the center and the symmetrically arranged room groups as well as the rooms for banquets and the dining rooms. The wide halls to the south and north of the peristyle have more parallels in the Mesopotamian area. The hall with a central column is also more typical of Mesopotamian buildings.

Residential buildings

The urban area was divided into rectangular blocks. So far only one block has been completely excavated. The houses are built from local limestone. The walls are made of rough, uncut stones. Gaps were filled with small stones and then smeared with mortar. The walls are usually around 70 to 80 cm thick, inner walls are usually a little thinner. There were bricks that prove that at least parts of the buildings had pitched or saddle roofs. The walls were probably once stuccoed and at least partially painted. Floors were made of tamped earth or clay. In some cases the actual rock may have served as the ground. An upper floor can only be occupied in one case, as a staircase has been preserved. There were cisterns in two houses. Cooking areas came to light in various rooms. Most of the residential buildings had a courtyard and were oriented to the north. The excavator calls the main room in the house the oikos . It was north of the courtyard and was often the most richly decorated room. It was bordered by identical rooms to the west and east, the function of which is uncertain. Fireplaces were often found in the Oikos.

The insula is 35 × 90 m in size and in a first phase was divided into two halves by a path. The individual houses were of different sizes. By far the largest was the house with the painted frieze (The House of the Painted Frieze) with a floor area of around 772 m². It had an entrance to the south, a large courtyard in the middle, and to the north of it a large hall decorated with painted stucco. It is a wall decoration in the so-called wall style . The wall was stuccoed and showed blocks modeled in the stucco, which were painted in color and partly imitated marble. A painted frieze showed erots. Such wall decorations are typical of many Hellenistic houses. Various construction phases can be distinguished. The painted hall belongs to the second phase, which is characterized by great prosperity. In the following and final phase, the house was apparently divided into various units. The room with the paintings was used as a workshop. The paintings were not restored, although they appeared to have been damaged.

Another large house was The South-West House, with a floor space of around 500 square meters. The entrance was in the north, from where one entered a small room and from there into a large courtyard. Most of the rooms in the house were arranged around this courtyard. Some rooms were provided with painted wall stucco. In various rooms there was also evidence of manual activities. This house, too, like all residential buildings in the city, was divided into smaller units in a final phase.

An example of a smaller house is North-East House 3 . It consisted of five rooms, some of which probably originally belonged to the neighboring house. The rooms are arranged one behind the other with a courtyard in the center. To the west of the courtyard were two larger rooms in which there were references to storage and textile processing. To the south of the courtyard there were two smaller rooms whose function is uncertain. At least one room was decorated with stucco.

The finds in the insula give indications of the activities of the residents, although the evaluation of the finds is problematic as the late phase of the location is overrepresented in the finds and many rooms and houses have changed their function and perhaps also their owners in recent years. Spinning whorls are evidence of textile processing. Various parts of stone mills and an iron sickle show that food was processed. Iron nails were often found near doors and may once have come from the wooden doors. Different knife blades were certainly used for different jobs. Weapons were also found, including the iron blade of a sword. Other iron or bronze objects are likely to have come from furniture. There were also many pieces of jewelry, such as rings, bracelets and pearls. Finally, various pieces came to light, including Astragaloi .

A little south of the insula, parts of a second block (Area S) have been excavated. He had at least two large courtyards and various rooms arranged around them. At least one room had columns. The building, or at least parts of it, seems to have fulfilled a public function. The excavators are considering the possibility that workshops, shops, and perhaps a market hall were located here.

The city wall

The city had an approximately 2.7 km long city wall, which was located on the north, west and south sides. The east side of the city lies on a slope and is therefore naturally protected. 21 towers or bastions could be identified. A tower in the north of the fortification was excavated. It is built of stone and has a floor plan of 4.24 × 7.75 m and is rounded on the outside. In the south, on the city side, there was a door. Two other towers flanking the city's capital gate have also been excavated. They are both square in plan with a side length of around 16.5 m, with an entrance on each side of the city. The two towers are about 12 m apart. In between, the city wall continues with an approximately 4.6 m wide passage in the middle.

graveyards

To the west of the city were the cemeteries, but their graves were found heavily robbed. 42 burials were unearthed, only one of which was not stolen. Some of the robberies took place in ancient times, but also in modern times. Ancient robberies were mostly aimed at metal objects, while ceramics were left in the grave. Modern grave robbers, on the other hand, also took complete vessels with them. Two types of graves could be identified: on the one hand there were burial chambers carved into the rock, on the other hand there were pits dug into the ground. The dead are body burials. The dead were usually in a wooden coffin, of which mostly sparse remains were preserved. Several of the dead wore jewelry. Smaller oil containers lay in the leg area. After the coffin was closed, a large vessel was usually placed in the grave pit. The pottery is coarse, although it is uncertain whether it was produced for the graves or whether coarse pottery not suitable for household use was sorted out by the living for the dead. Most of the burials date back to the second century BC. About 10% of the graves date to Byzantine times.

Finds

Most of the finds include ceramics. Most of the vessels appear to have been made locally. In their forms they mostly follow Hellenistic types. There were also numerous fragments of Eastern Sigillata , which may have been produced in Antioch . Some of the fragments bear short inscriptions, most of them in Greek. Rhodian amphorae are often stamped with the names of Rhodian producers; they mostly date to around 200 BC. The stamps of later amphorae bear the Semitic name Abidsalma, which was undoubtedly a regional trader. This could indicate that oil and wine imports lost importance in later times. Perhaps this was the result of dwindling prosperity, but it may also prove that regional suppliers, such as Abidsalma, came into play. Many clay lamps and numerous terracotta figures also came to light. Most of them follow Hellenistic models, but there are also figures of the Astarte and the Persian rider . The Persian horsemen are of some importance in terms of research history. Until now it was unclear whether such figures only date to the time of the Achaemenid Empire or whether they were also produced later, as some other finds suggested. The figures in Jebel Khalid now clearly show that they were still produced in the Seleucian period. Numerous spindle whorls show that textiles were processed in the city. Fragments of numerous glass vessels have also been excavated. These are mostly bowls that were used as drinking vessels and for the most part date to the late Hellenistic period (125 to 70 BC). Blown glass was rarely found and comes from later sporadic residents of the area. The technique of glass blowing only found widespread use in Roman times. The place of manufacture of most glassware is difficult to determine.

The numerous coins found are especially important for dating. A high percentage of them come from Antioch on the Orontes , the capital of the Seleucid Empire. This may indicate that soldiers stationed in the city were paid from there. At the governor's palace, a small, only 6 cm high bronze statuette showing a naked man emerged. At the main gate there was a fragment of an 8 cm high leg or ivory tablet showing a standing soldier or god. It may be an insert for a piece of furniture. Various Hellenistic seal impressions have also been found; the motifs are an anchor, the representation of Zeus and several images of Athena .

Excavations

The ruins of the city were identified as an important archaeological site during site inspections by an Australian team in 1984. The pottery indicated that Greeks lived here. It was also clear from the start that there was no previous settlement worth mentioning here. The remains were also easy to dig out because they are just below the surface. However, the city was used as a quarry early on, so that some of the buildings in prominent locations were poorly preserved. This particularly affected the temple with its numerous large and well-hewn stone blocks. The excavators report that shortly before the excavations, decorated altars were collected and transported to Manbij. A search for the whereabouts of the blocks was unsuccessful. Between 1986 and 2010 excavations by the Australian National University and the University of Melbourne took place in Jebel Khalid . They were under the joint direction of Peter James Connor (from 1986 until his death in 2006), Graeme Clarke (from 1986), Heather Jackson (from 2000) and John Tidmarsh (from 2006). In the first two excavation campaigns (1986/1987), excavation cuts were made in the urban area to see where excavations were particularly worthwhile. Systematic excavations then took place from 1988. In 2010 the excavations had to be stopped due to the uncertain political situation in Syria after the beginning of the Arab Spring .

Significance for archeology

The special significance of Jebel Khalid lies primarily in the fact that there are only a few other equally well-preserved Seleucid settlements. Ai Khanoum in present-day Afghanistan can only be cited as another example . Another advantage is the fact that the settlement area was no longer permanently inhabited after the fall of the city, so the settlement structures are not destroyed or impaired by later development. Since the city only existed for about 200 years, a large part of the finds can be easily dated, which in some cases allows conclusions to be drawn from finds at other excavation sites or from archaeological objects that cannot be reliably identified (e.g. the Persian horsemen ). In Jebel Khalid you can also follow the arrival of Greek settlers and their interaction with the old, local population.

literature

- Getzel M. Cohen: The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa (Hellenistic Culture and Society 46), Berkeley 2006, ISBN 978-0-520-24148-0 .

- GW Clarke: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 1: Report on Excavations 1986-1996, Eisenbrauns 2002, ISBN 978-0-9580265-0-5

- Heather Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 2: The terracotta figurines, Sydney: MEDITARCH, 2002, ISBN 978-0-9580265-2-9

- Heather Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 3: The Pottery, Sydney: MEDITARCH, 2011, ISBN 978-0-9580265-3-6

- Heather Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 4: The housing insula, Sydney: MEDITARCH, 2014, ISBN 978-0-9580265-5-0

- G. Clarke, H. Jackson, CEV Nixon, J. Tidmarsh, K. Wesselingh and L. Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010, Mediterranean Archeology supplement, 10. Sydney: MEDITARCH Publications; Sydney University Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0-9580265-7-4

- Karyn Wesselingh: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates , Volume 6: A Zooarchaeological Analysis, Sydney: MEDITARC 2018, ISBN 978-0-9580265-8-1

Web links

- Literature by and about Jebel Khalid in the WorldCat bibliographic database

- Graeme Clarke & Heather Jackson: Can the mute Stones speak? Evaluating cultural and ethnic identities from archaeological remains: the case of Hellenistic Jebel Khalid ( online )

- Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates (Documentation from the University of Melbourne)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Nicholas L. Wright: The Last Days of a Seleucid City: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates and its Temple, in: Kyle Erickson and Gillian Ramsey (eds.): Seleucid Dissolution The Sinking of the Anchor, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978 -3-447-06588-7 , p. 117.

- ↑ CEV Nixon: Jebel Khalid: Catalog of the Coins 2000–2006 , Mediterranean archeology, 2008-01-01, Vol. 21, pp. 119–161, here especially pp. 120–123.

- ↑ M. Mottram and D. Menere: Wadi Abu Qalqal Regional Survey, Syria - Report for 2006 . 1-40. Meditarch. 2007, p. 5.

- ^ The Jebel Khalid site .

- ^ G. Clarke: Brief Overview , in: Clarke, Jackson, Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010, p. 440.

- ↑ Nicholas L. Wright: The last days of a Seleucid city: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates and its temple , in: K. Erickson and G. Ramsey (eds.): Seleucid Dissolution, The Sinking of the Anchor , Wiesbaden, ISBN 978 -3-447-06588-7 , pp. 117-132, here 118.

- ↑ M. Motram: Emerging evidence for the pre-hellenistic occupation of jebel khalid , in: Mediterranean Archeology 26 (2013), p. 47.

- ↑ Getzel M. Cohen: The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa , University of California Press, Berkelet, Los Angeles, London 2006, ISBN 978-0-520-24148-0 , S. 178th

- ^ G. Clarke: Brief Overview , in: Clarke, Jackson, Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010 , pp. 442-443.

- ↑ G. Clarke: letter Overvies , in Clarke, Jackson, Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010, pp 444-445.

- ^ M. Mottram: Settlers, Hermits, Nomads and Monks: Evolving Landscapes at the Dawn of the Islamic Era , in: Roger Matthews and John Curtis (eds.): Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Archeology of the Ancient Near East 12 April - 16 April 2010, the British Museum and UCL, London , Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-447-06685-3 , pp. 533-550.

- ↑ G. Clarke: letter Overvies , in Clarke, Jackson, Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010, pp 440-441.

- ^ Graeme Clarke: The Jebel Khalid Temple , in Mediterranean Archeology, 2006/07, Vol. 19/20, pp. 133-139.

- ^ G. Clarke: Area C, The Palaestra , in: Clarke, Jackson, Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010, pp. 37-47.

- ↑ GW Clarke: The Governor's Palace, Acropolis , in: GW Clarke: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 1: Report on Excavations 1986-1996, pp. 25-48.

- ↑ Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 4: The housing insula, pp. 19-44.

- ↑ Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 4: The housing insula, p. 5.

- ↑ Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 4: The housing insula, pp. 45–116.

- ↑ Heather Jackson: Erotes on the Euphrates: A Figured Frieze in a Private House at Hellenistic Jebel Khalid , American Journal of Archeology, Apr., 2009, Vol. 113, No. 2, pp. 231-253.

- ↑ Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 4: The housing insula, pp. 165–241.

- ↑ Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 4: The housing insula, pp. 379-396.

- ↑ Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 4: The housing insula, pp. 565-603.

- ↑ Jackson: Area S. The Commercial Area , in: Clarke, Jackson, Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000–2010, pp. 49–76.

- ^ P. Connor, GW Clarke: The North-West Tower , in: GW Clarke: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 1: Report on Excavations 1986-1996, pp. 1-15, and GW Clarke: The Main Gate , ibid , Pp. 17-23.

- ^ Judith Littleton, Bruno Frohlich: Excavations of the Cemetery - 1996 and 1997 , in: Clarke: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 1: Report on Excavations 1986-1996, pp. 49-69.

- ^ Clarke: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 1: Report on Excavations 1986-1996, p. 288.

- ↑ Jackson: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 2: The terracotta figurines, 2002; Jackson: Figurine Fragments , in: Clarke, Jackson, EV Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010, pp. 146-206.

- ↑ Heather Jackson: The Case of the Persian Riders at Seleucid Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates: The Survival of Syrian Tradition in a Greek Settlement , in: Demetrios Michaelides, Giorgos Papantoniou, Maria Dikomitou - Eliadou (eds.): Hellenistic and Roman Terracottas ( Monumenta Graeca et Romana), Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden 2019, ISBN 978-90-04-38483-5 , pp. 383-394, especially p. 393.

- ↑. MO Hara; The Glass , in: Clarke: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 1: Report on Excavations 1986-1996, pp. 245-260.

- ↑ CEV Nixon: The coins from Jebel Khalid, a Hellenistic city in Syria. , in: Journal of the Numismatic Association of Australia 17 (2006), pp. 92-93.

- ^ H. Jackson: Figurine Fragments , in: Clarke, Jackson, EV Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010, pp. 145-146.

- ↑ H. Jackson: Figurine Fragments , in: Clarke, Jackson, EV Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010, pp. 207-211.

- ^ Clarke: Four Hellenisctic Seal Impressions, in: Clarke: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 1: Report on Excavations 1986-1996, pp. 201-203.

- ^ Clarke, Jackson, Nixon, Tidmarsh, Wesselingh and Cougle-Jose: Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates, Volume 5: Report on Excavations 2000-2010 , p. 12.

- ^ The Australian Mission to Jebel Khalid .

- ↑ Laurianne Martinez-Sève: The Spatial Organization of Ai Khanoum, a Greek City in Afghanistan , in: American Journal of Archeology 118 (2014), pp. 267-283