Big crook and cellar trade

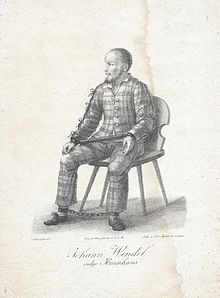

The large crook and cellar trade from 1824 to 1827 is considered to be the “greatest sensational process of the restoration period ” in Switzerland . In the course of the trial, the authorities and the media stylized the main suspects Klara Wendel (1804–1884) and her older brother Johann ( Krusihans , 1795–1831) as heads of a dangerous gang of robbers . Klara confessed and denounced 20 murders, 14 arson attacks and 1,588 thefts. Even before the trial was over, Klara's denunciations led to the Richterswil Conference , which decided on intercantonal cooperation in the persecution of the “crooks” in Switzerland.

Death of Schultheiss Franz Xaver Keller (1772–1816)

On the evening of September 12, 1816, the liberal Lucerne mayor Franz Xaver Keller and his two daughters left the city of Lucerne for the Geissmatt estate. In the dark and in heavy rain, they chose a narrow path along the Reuss . A daughter went ahead, the father in the middle. When the second daughter reached the estate before her father, they and neighbors set out to find the mayor. Three days later, Franz Xaver Keller's body was found on the banks of the Reuss. A forensic medical certificate recorded an accident as the cause of death. As early as September 1816, however, rumors spread that ultramontane circles had the liberal politician murdered.

Arrest of Klara Wendel (1804-1884)

In June 1824, Schwyzer Landjäger arrested the twenty-year-old homeless Klara Wendel in Einsiedeln for stealing . The authorities suspected her of selling stolen property from a break-in in Näfels (Canton Glarus ). Under precarious prison conditions and in constant fear of physical violence, Klara denounced a large number of relatives and acquaintances, above all her brother Johann ( Krusihans ) and her brother-in-law Josef Twerenbold. On June 19, 1824, officials from Schwyz brought her to Glarus, where the trial was to take place.

Trial in Glarus

During further interrogations in Glarus , Klara Wendel confessed to the Glarus doctor and interrogator Jakob Heer not only that she had broken into Näfels herself, but also told of a myriad of other offenses in which she was involved or which she had heard of. As a result, the Glarus authorities searched for the suspects and described them as members of a dangerous band of robbers.

The continuous admission of further offenses and the denunciation of a large number of alleged accomplices soon gave Klara the status of a key witness . The investigative interrogation commission was less interested in clearing up the individual cases than in convicting a "dangerous gang of crooks". Already in the early course of the trial, Klara's stories had a decisive influence on its further course, whereby her ability to "verify what was said with ever new stories, to captivate the interrogators and, above all, to find out what interested them" was notable, whereby the "hint acrobatics" worked above all with those stories "which were based on a factual core and for which it could bring the possibility of another explanation into play". For example in the death of Franz Xaver Keller - although Klara was only 12 years old in 1816. By constantly asking the interrogation committee to elaborate on what was said, Klara continued to develop the stories.

The other suspects arrested in Glarus were brought to Lucerne in January 1825 . On June 1, 1825, almost six months later, the Landjäger also took Klara Wendel to the place where the Glarus Trial was continued.

Trial in Lucerne

17 men, 21 women and 27 children were arrested with Klara Wendel and placed in various Lucerne prisons. In addition to the Glarner Jakob Heer, Josef Franz Karl Amrhyn (1800–1849) in particular acted as an interrogator in Lucerne - the son of the incumbent Lucerne mayor and Keller's successor, Josef Karl Amrhyn .

In the fall of 1825, after months of imprisonment under precarious conditions, after beatings, chain sentences and lying sentences and several confrontations with his sister Klara , Johann Wendel stated that he had committed the murder of Franz Xaver Keller with four other accomplices. As principal gave as Krusihans the two Klara aristocratic - conservative and church-friendly Lucerne government councils Leodegar Corragioni d'Orelli (1758-1830) and Joseph Pfyffer of Heidegg (1759-1834) from the family Pfyffer von Altishofen on.

With Johann Wendel's confession and the imprisonment of the two government councilors Corragioni and Pfyffer, the previous «crook process» became the so-called cellar trade - now the investigations no longer revolved around a murderous gang of robbers, but rather political murder and thus a state crime. As a consequence, the process was divided into a «crook» and a «basement process».

However, since the interrogator Amrhyn found a new field of activity as a federal state clerk in Bern and the Lucerne prisons were overcrowded, Lucerne was unwilling to continue the process.

Trial in Zurich

On December 3, 1825, the later Zurich government councilor Heinrich Escher (1789–1870) took over the “basement trial” and the criminal actuary and secretary of the central police department in Bern Jakob Emanuel Roschi (1778–1848) was appointed interrogator in the “crook trial”.

Escher quickly uncovered glaring deficiencies in the previous litigation: For example, the daughters of Franz Xaver Keller were never questioned, the statements of the suspects did not completely match and came about as a result of psychological and physical violence. They were also held in catastrophic conditions for several months. Johann Wendel and Josef Twerenbold revoked their previous confessions during the first interrogation of the new commission. It was not until the eleventh interrogation on March 17, 1826 that Klara Wendel declared that she had never participated in any murder and had never observed one. Klara justified the constant construction of new stories with the fact that the interrogators of the Glarus and Lucerne trials constantly demanded further and new statements, which is why she began to invent events that were as plausible as possible in order to meet these expectations.

Jakob Emanuel Roschi also uncovered deficiencies in the previous process management. Only the offenses and crimes of the accused are listed, but the statements of the detainees have not been verified. In addition, the same crimes were sometimes logged and counted several times. In many cases, the prisoners only stood in the hope that the trial - and thus the pre-trial detention in the prison towers - would finally come to an end. At the end of the trial, the interrogation commission still counted 1,255 thefts, with the loot mostly being clothes, food, metal and general goods that had been stolen in a total of 14 cantons and the Principality of Liechtenstein . Roschi also pointed out, however, that the delinquents often committed the thefts out of sheer necessity. The increasing persecution of the non-residents meant that they could no longer pursue their trade.

Judgments

Nonetheless, the trial had grave consequences for many of the accused: in 1826, Leodegar Arnold, Basil Germann and Johann Kiwiler were publicly executed with the sword in Lucerne as “incorrigible thieves”. The judges sometimes imposed long-term chain sentences and imprisonment against others. Klara Wendel, her sister Barbara and the mother Katharina Dreyer should also be sentenced to death. However, the courts reduced the sentences to twelve years' imprisonment for Klara and her mother and ten years for Barbara. After that, they should be banned from the Swiss Confederation or, if a citizen right has been brokered for them in the meantime , they should no longer be allowed to leave this municipality. Klara's brother Johann was sentenced to twelve years of chain imprisonment, after which he was no longer allowed to leave his home community.

The court found neither the “crooks” nor the Lucerne councilors Joseph Pfyffer von Heidegg and Leodegar Corragioni d'Orelli guilty of the murder of Franz Xaver Keller. Escher suspected a political conspiracy against the conservative Lucerne, the originator of which he suspected in the radicals Vitalis Troxler (1780–1866) and Ludwig Snell (1785–1854). This accusation is described by research as fanciful and constructed. Klara Wendel's denunciation of the alleged client came in handy for the interrogators in the context of their party-political standpoint.

Kidnappings

At the initiative of the Lucerne section of the Swiss Charitable Society (SGG), all 23 children who had been imprisoned with their parents were "cared for" after the trial. The aim of the measure was to wrest the children from their earlier way of life and to integrate them into the middle-class, settled society. One way of doing this was to assign new family names, for example “Freund” or “Fründ” instead of “Wendel”, “Wacker” and “Ehrlich” instead of “Wächter”, “Humility” instead of “Feuchter”, “Redlich” instead of “Germann” "Or" Schwyzer "instead of" Twerenbold "and" Arnold ".

swell

- Heinrich Escher: Historical presentation and examination of the criminal procedure seduced by the denounced murder of Mr. Schultheiss Keller, Sel. Von Luzern. HR Sauerländer , Aarau 1826. ( digitized from Google Books)

- Julius Eduard Hitzig and Wilhelm Häring (eds.): The new Pitaval . A collection of the most interesting crime stories from all countries from earlier and more recent times , Volume 4. Brockhaus , Leipzig 1843, pp. 395–448. ( Digitized from Google Books)

literature

- Brigitte Baur: Telling in court. Klara Wendel and the 'big crook and cellar trade' 1824–1827. Chronos , Zurich 2014, ISBN 978-3-0340-1223-2 .

- Thomas Huonker : Traveling people - persecuted and ostracized. Yenish résumés. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1990, ISBN 3-85791-135-2 .

- Thomas D. Meier and Rolf Wolfensberger: A home and yet none. Homeless and non-settled people in Switzerland (16th – 19th centuries). Chronos, Zurich 1998, ISBN 978-3-905-31253-9 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), p. 402.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), p. 405.

- ^ Gregor Egloff: Wendel, Klara. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), pp. 273-277.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), p. 121.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), p. (201)

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), p. 240.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), pp. 294-305.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), p. 362.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), pp. 363-365 and 371.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), pp. 381 and 383.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), pp. 402-406.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), pp. 410-412 and 419-420 and Meier / Wolfensberger (see literature), p. 397.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), p. 398.

- ↑ Huonker: Traveling People. (See literature), p. 41.

- ^ Baur: Telling in court. (See literature), pp. 425-426 and Huonker: Fahrendes Volk. (See literature)