Kingdom of Bamum

The Kingdom of Bamum or Bamun , also known as Mum , was a pre-colonial state in what is now northwestern Cameroon in West Africa. The state, founded in 1394 and independent until 1884, was established by the Bamum , a Semibantu people from the highlands of Western Cameroon .

founding

The Bamum, like several other Cameroon highland peoples, originally descended from the Tikar from the Cameroon grasslands . In fact, the Kingdom of Bamum was founded by immigrants related to the Tikar royal dynasty of the Nsaw. The founder and first king (called “ Fon ” or “Mfon”) of the empire was Nchare , a conqueror who is said to have defeated 18 rulers. King Nchare also founded the capital Foumban , then called Mfomben. This first group of Tikar-speaking immigrants and conquerors absorbed the Bamun language and the customs of their new subjects and were henceforth known as Bamum. Later all the peoples under their influence took this name. The Chamba migration from the Tikar plain in the southern part of the western highlands of Adamaua also resulted in the establishment of the kingdom.

organization

The founder of the empire organized the country as king through political institutions that arose from the Tikar. There were titled and noble people who were called kom ngu (English embassy councilors of the kingdom ) and with whom he ruled the country. Secret societies were active among the population of the Kingdom of Bamum . The ngiri association was made up of princes and princesses, while the mitngu association was open to the general population, regardless of social status. The king of Bamum was known as the Mmfon , a title also used by the Tikar rulers. Most of the time, the Mfon sought his followers among the twins and the sons of the princesses. The Mfon participated intensively in the nationwide widespread polygamy , which led to an increase in the ruling family and an increasing palace nobility .

Nobility title

| Nobility title | Literary translation | Role and functions | Appointment and Succession |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mfon | king | sovereign | hereditary office |

| Com | Minister (co-founder) | Enthronement Advisor | appointed, hereditary thereafter |

| Nafom | Mother of the king or royal mother | Balance of power | appointed |

| Nji Ngbetigni | Associate Nji | Viceroy | hereditary |

| Pom Mafon | brother or sister | Guardianship of the King | hereditary |

| Nji Fon Fon | Nji of kings | Prime Minister | appointed |

| Tita Nfon | Father of the king | King father | appointed |

| Tita Ngu | Father of the country | Head of Justice | appointed |

| Tupanka | Head of panka | Commander in Chief of the Royal Army | appointed |

| Kom Shu Mschut | Guardian of the palace | Advisor to the king | hereditary |

| Manschut | Great of the palace | Kingdom personality | appointed |

| Mfontue | Devoted king | Vassal chiefs | hereditary |

| Schunschut | Palace guard | various services | hereditary |

| Caps | slave | operator |

Culture

Originally the state language in the Kingdom of Bamum was the Tikar language . This did not last long, however, and in time the language of the conquered, Mben , was adopted. The economy was predominantly agricultural and slavery was only practiced to a limited extent. The Kingdom of Bamum also traded with neighboring states. Mainly salt , iron , pearls , cotton goods and copper objects were imported .

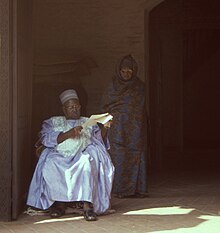

The Bamum developed a wide-ranging art culture in their capital, Foumban , which achieved worldwide fame at the beginning of the 20th century. During Ibrahim Njoya's reign, six dye pits containing several different colors were preserved. The Bamum also imported indigo- dyed raffia dresses from the Haussa as royal clothing. This royal garment was called ntieya, and Haussa artisans worked for the king in the palace supplying nobles and teaching the art of dyeing .

history

During the 18th century, the kingdom faced a threat from invasion by Muslim Fulani fighters and the Chamba . Towards the end of the century the Bamum had only 10,000 to 12,000 inhabitants in their domain. The history and customs of the Bamum list a total of ten kings between the founder and Kuotu . The nine kings who succeeded Nchare were no longer conquerors, and territorial expansion continued until the reign of the tenth Fons, Mfon Mbuembue, in the late 19th century. King Mbuembue was the first ruler to re-expand the kingdom of Bamum. He is also famous for the repulse an attack by the Fulani in the early 19th century, which in the course of the Fulani jihad to Islam would spread by force. Mfon Mbuembue also took steps to fortify the capital, Foumban, with a trench. He was the founder of the Ngnwe peh tu . This emblem representing the Bamum people shows a snake with two heads and stands for the ability to wage war on two fronts and to win on both fronts.

German colonization

The Kingdom of Bamum voluntarily became part of the German Cameroon colony during the reign of Mfon Nsangou in 1884 . During his reign the country was at war with the Nso . At the end of the conflict, the king fell too, and his head fell into the hands of the Nso. Immediately afterwards, one of the king's wives , Njapdunke , and her lover Gbetnkom Ndo`mbue took over the king's official duties. The latter, however, was not allowed to rule as he was not the son of King Mfon Mbuembue the Great Conqueror or was descended from his line. In fact, after Mfon's death there was no male heir to the throne to replace the king; therefore Njapdunke performed the duties of the king for a period of time, but not enough to represent the king. Eventually she was deposed and Gbetkom , a son of the penultimate king, was installed as the new Mfon. Gbetkom was a man of relatively small size and ruled extremely repressively. He created a royal dictatorship in which the legs of those taller than him were chopped off - a practice that eventually cost him his life during a hunting lesson. After his death, his young son Mbiekouo officially succeeded him, but he was too young to rule. It became a habit of him to want to know who of the bodyguards protecting his father was. Since the royal court led by Ngouhouo increasingly feared that the boy would recognize his father's murderers in them, they murdered him too. The place where this happened is now called "Mfe shot Mfon mbwere" to honor Mbiekouo. Now the throne was vacant for a period and Ngouhouo, head of the court, became Mfon. However, he did not come directly from the line of King Mbuembue, but was born as a Bamileke slave. Ngouoh was not welcomed by the people and he decided to move the palace to his own hometown. Ultimately, supporters of the former King Mbuembue managed to defeat him and ban him from the empire. A grandson of Mbuembue, Nsangou, became the new king.

Njoya the great

Eventually King Njoya , son of the murdered king, came to power. He ruled from 1883 to 1931 and was one of Bamum's most productive rulers as he was responsible for modernizing numerous elements of Bamum society. He voluntarily placed his kingdom under the protection of the German colonial power by concluding a protection treaty with the German Empire . In 1897, Njoya and his court converted to Islam , a decision that had an impact on the Bamum culture long after Njoya's death. The monarch received the title Sultan from now on . He developed the Schümom script with the intention that the Bamum people could record the history of their empire. In 1910 Njoya introduced a new school system and established schools across the country in which the Schümon script was taught. The Germans were allowed to set up their Basel Mission in the capital Bamums and construction work was carried out to build a temple. A school was built in which the German language and the Bamum language were taught. Under the German protection regime, new housing construction techniques were also introduced, as many Germans settled among the natives of the empire as farmers, traders and teachers. Sultan Njoya remained loyal to his German overlords , who in return respected his rights as king and advised him on colonial trade. Another important element in the kingdom's history during the period under German patronage was the introduction of the sweet potatoes , macabo, and other new foods that helped the kingdom become more prosperous than ever. The Bamum already acted on a larger scale outside of their traditional borders, but the new income during the German colonial era noticeably increased the standard of living. Sultan Njoya was heavily influenced by missionaries who aimed to abolish the practice of idols , polygamy and human sacrifice . In response, Njoya restricted royal excesses. Nobles were allowed to marry landless people from the lower classes and even slaves. The king himself, however, did not convert to Christianity . In fact, he incorporated elements of Christianity and Islam into the traditional faith of the Bamum in order to found a new religion that would be more convenient for the subjects.

In 1906, the government of German Cameroon sent an expeditionary force against the Nso, supported by Sultan Njoya's soldiers. After the German-Bamuman victory over the Nso, the troops managed to win back the head of Njoya's father, which was extremely crucial for the legitimation of the king. From then on, the union between Bamum and Germany was described as unbreakable.

French conquest

When German Cameroon was threatened at all borders during the First World War (→ Cameroon in the First World War ), it was supported by the Kingdom of Bamum against the invasion of British and French troops until the end of the war . The end of German colonial rule was felt to be disadvantageous, as the French who followed were clearly more repressive.

In 1919 the German colonial possessions in Cameroon were divided between France and Great Britain. The territory of the kingdom was divided between the two League of Nations mandates: British Cameroon and French Cameroon . The Bamum kingdom itself came mostly under the rule of France and was directly subordinate to the League of Nations mandate of French Cameroon. French rule was much more repressive than German. In 1923 Sultan Njoya was dethroned and deposed by the French and the Bamun script was banned. The use of German and the Bamum language in schools was also abolished and only French was allowed in the education system.

List of kings and sultans

- Nchare Yen 1394-1418

- Ngoupou 1418-1461

- Monjou 1461-1498

- Mengap 1498-1519

- Ngouh I. 1519-1544

- Fifen 1544-1568

- Ngouh II. 1568-1590

- Ngapina 1590-1629

- Ngouloure 1629-1672

- Kouotou 1672-1757

- Mbouombouo 1757-1814

- Gbetkom 1814-1817

- Mbiekouo 1817-1818

- Ngouhouo 1818-1863

- Ngoungoure 1863 (30 minutes)

- Nsangou 1863-1889

- Ibrahim Njoya 1889-1933

- Njumoluh Njoya 1933-1992

- Mbombo Njoya 1992 - present

literature

- Emmanuel Matateyou: Paroles sapientiales du royaume Bamoun (nkù nsa nsa) . Oralistique, 1990.

- Michael S Bisson, S. Terry Childs, Philip de Barros, Augustin FC Holl: Ancient African Metallurgy: The Sociocultural Context . Alta Mira Press, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-08704-4 .

- Ian Fowler, David Zeitlyn: African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon . Berghahn Books, Oxford 1996, ISBN 1-57181-926-6 .

- Albert S. Gérard: European-language Writing in Sub-Saharan Africa Vol. 1 . John Benjamin Publishing Company, Budapest 1986, ISBN 963-05-3832-6 .

- Bethwell A. Ogot: General History of Africa V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century . University of California Press, Berkeley 1999, ISBN 0-520-06700-2 .

- David McBride, Leroy Hopkins, C. Aisha Blackshire-Belay: Crosscurrents: African Americans, Africa, and Germany in the Modern World . Boydell & Brewer, Rochester 1998, ISBN 1-57113-098-5 .

- Claire Polakoff: African Textiles and Dying Techniques . Routledge, Garden City 1982, ISBN 0-7100-0908-9 .

- Mohamad Z. Yakan: Almanac of African Peoples & Nations . Transaction Publishers, Edison 1999, ISBN 0-87855-496-3 .