Fatty liver

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| K70.0 | Alcoholic fatty liver |

| K76.0 | Fatty liver (fatty degeneration), not elsewhere classified |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The fatty liver ( Latin steatosis hepatis , from ancient Greek. Στέαρ stéar , Gen .: στέατος stéatos, German fat, tallow and ancient Greek. Ἧπαρ hepar , German liver ) is a common disease of the liver with usually reversible storage of fat ( triglycerides ) in the liver cell ( hepatocyte ) in the form of fat vacuoles, e.g. B. through overeating (hyperalimentation), through various genetic disorders of lipid metabolism (e.g. abetalipoproteinemia ), alcohol or drug abuse , toxins and other poisons , diabetes mellitus , pregnancy , protein deficiency, liver congestion, liver removal or bypass operations that switch off parts of the small intestine .

If signs of inflammation (increased "liver values" = increased transaminases ) can be detected in addition to fat deposits , this is called fatty liver hepatitis (steatohepatitis). Fatty liver often goes undetected for a long time; partly because it does not cause pain. It can then develop into life-threatening cirrhosis of the liver , which can lead to serious complications such as ascites , variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy . The Hepatic encephalopathy is considered a marker for a particularly drastic course of liver cirrhosis. Due to the increasing number of people with obesity and metabolic syndrome, the importance of fatty liver hepatitis (NASH) and its precursor, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), as causes of liver cirrhosis is steadily increasing. Some projections speak of an up to 56% increase in NASH prevalence for China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, Great Britain and the United States by the year 2030.

Pathophysiology

Fatty liver is based on a disturbance of the fatty acid and triglyceride metabolism of the liver cells and can therefore have different causes. A very large proportion of fatty liver diseases is based on a disproportion between the energy supply through food and the energy expenditure through exercise, which leads to a positive energy balance . The metabolism stores excess energy as body fat . a. also on the liver. For this reason, fatty liver and obesity have been linked.

Hereditary (hereditary) metabolic disorders are also common, in which the formation of lipids in the liver and their discharge from the organ are disturbed (increased or decreased). These steatoses due to hereditary metabolic disorders or enzyme defects are usually not directly related to obesity or malnutrition. This also applies to fatty liver disease as a result of systemic diseases such as Wilson's disease , hemochromatosis and abetalipoproteinemia and similar diseases. In normal weight patients with fatty liver disease, an underlying disease should always be searched for.

Fatty liver problems are common in alcoholism . With a calorific value of 29.7 kJ / g (= 7.1 kcal / g), alcohol is very rich in energy. Metabolism with the help of the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) initially produces the intermediate product acetaldehyde . This is metabolized by aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH-2) to acetate, which in turn reacts with coenzyme A and ATP to form the energy carrier acetyl-CoA. When alcohol is broken down by ADH, excess NADH is produced, so that the NADH / NAD quotient is increased. This means that the acetyl-CoA that is formed cannot be broken down and is essential for the formation of fatty acids. a. is used in the liver (with increased levels of ATP in the liver, the citric acid cycle is inhibited). Since acetaldehyde damages the transport system for fats that are supposed to leave the liver, the fats cannot leave the liver. The fatty acids are esterified into triglycerides (fat). These stay in the liver and the result is fatty liver. The triglyceride concentration in the liver in healthy people is around 5%, in fatty liver it can be up to 50%. This fatty liver is initially completely reversible and only leads to irreparable damage over time. Their development in connection with persistent, often chronic inflammatory reactions often goes unnoticed for years or decades. Similar to physiological wound healing, reactive fibrosis leads to an increase in connective tissue and regenerated nodules, which heal within a few days in the event of short-term damage. If the damage persists, however, the lobule and vessel architecture change until the liver becomes scarred and thus cirrhotic . Once this process of organ structuring is complete, it can usually no longer be reversed - one speaks of cirrhosis of the liver . This can lead to serious complications such as ascites , variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy .

Fatty liver can also occur as a result of chronic malnutrition (for example malnutrition ), insofar as this also applies to anorexia . Glycogen is usually formed and stored in the liver from carbohydrates ( breakdown units of carbohydrates → monosaccharides such as glucose ). This quickly provides energy through glycogenolysis. If the carbohydrate stores are empty, gluconeogenesis begins . Glucose is synthesized in the liver and kidneys from non-carbohydrate precursors, e.g. B. glucoplastic amino acids, which are obtained from degraded muscle protein, especially when you are hungry. If insufficient protein (0.8 g / kg body weight per day) is supplied as a result of malnutrition or hunger, gluconeogenesis is disrupted because the energy from muscle and connective tissue cells required to burn fat is insufficient. Unmetabolized fats ( triglycerides ) are deposited on and around the liver.

An increase in the SHBG protein increases the risk of adult diabetes .

Classification

- 1. Simple fatty liver

- 1.1. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

- 1.2. Alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD)

- 2. Fatty liver inflammation

- 2.1 Non-alcoholic fatty liver inflammation (NASH = non-alcoholic steatohepatitis )

- NASH grade 0 fat storage without inflammation

- NASH grade 1 fat storage with slight inflammation

- NASH grade 2 fat storage with moderate inflammation

- NASH grade 3 fat storage with severe inflammation.

- 2.2. Alcoholic fatty liver inflammation (ASH = alcoholic steatohepatitis)

- 2.1 Non-alcoholic fatty liver inflammation (NASH = non-alcoholic steatohepatitis )

- 3. Fatty liver cirrhosis

The simple fatty liver can go unnoticed and without symptoms for years. If inflammation of the liver ( steatohepatitis ) can be demonstrated, the disease can progress to liver cirrhosis (in approx. 10% of cases) and ultimately to hepatocellular carcinoma. Serious complications of liver cirrhosis such as ascites , variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy often occur in these late stages of the disease

Fatty liver is a common disease. Approx. Fatty liver is 25% of the western adult population. Fatty liver is believed to be caused by an unhealthy lifestyle. It is associated with obesity, diabetes and a lack of physical activity. The fatty liver is probably an early sign of the metabolic syndrome, prediabetes .

Diagnosis

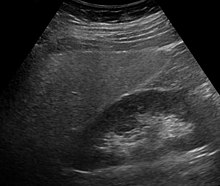

Fatty liver disease is most noticeable in sonography due to enlargement and increased echogenicity compared to the kidney as well as due to a clumsy form or in computed tomography or magnetic resonance tomography . If a liver biopsy is performed for other reasons , the fatty liver can also be confirmed histologically . No reliable evidence can be obtained from laboratory chemistry, however, slightly elevated transaminases and an elevated γ-GT are often noticeable. There is also the possibility of calculating the fatty liver index, which can predict the likelihood of the presence of fatty liver. The severity can be determined using special magnetic resonance imaging or elastography methods.

therapy

The treatment of fatty liver disease must always be based on the underlying cause. Since these can be very different, the therapies also differ significantly. Fatty liver (with no signs of inflammation of the liver) usually has little disease value. However, since it can develop into steatohepatitis and it can be an early sign of the metabolic syndrome , it must be evaluated medically and treated early.

- Fatty liver acquired nutritionally (diet-related) is mainly treated with nutritional therapeutic measures. A balanced, healthy diet with reduced calories is often sufficient to completely regress the fat deposits. If the patient is very overweight ( obese ), a low-calorie diet should be considered prophylactically.

- Toxic fats in the liver ( alcohol , medication, drugs, poisons) are treated by leaving out the triggering substance. Acute liver damage caused by paracetamol is treated with the antidote acetylcysteine .

- In the case of non-diet-related fatty liver disease (e.g. hereditary mitochondrial diseases, storage diseases and disorders of β-oxidation ), which can also affect slim people, dietary treatment is not the focus. Usually, in addition to treating the underlying defect, drugs that stabilize the cell membrane, antioxidants or lipid-lowering agents are used.

tissue

Histologically, a distinction is made between the large droplet (macrovesicular) form with displacement of the cell nucleus to the edge and the small droplet (microvesicular) fatty liver cells and transitional forms. The large drop form is z. B. in the ASH (alcoholic steatohepatitis), the small drop z. B. in pregnancy obesity.

See also

literature

- S2k - Guideline for non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS). In: AWMF online (as of 2015)

Web links

- Microscopic image of fatty liver with NASH

- Online tool to determine the likelihood of fatty liver disease (fatty liver index)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Classen, Diehl, Kochsieck: Internal Medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer-Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-437-42830-6 , pp. 1260-1262.

- ↑ P. Jepsen et al. In: Hepatology , 2010, 51, pp. 1675-1682.

- ↑ PMID 27722159 PMC 5040943 (free full text)

- ↑ PMID 29886156

- ↑ SP Singh, B. Misra, SK Kar: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) without insulin resistance: Is it different? In: Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec 17. doi: 10.1016 / j.clinre.2014.08.014

- ↑ Johannes Weiß, Monika Rau, Andreas Geier: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease epidemiology, course, diagnosis and therapy. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 111, issue 26 from June 27, 2014.

- ^ Gertrud Rehner, Hannelore Daniel: Biochemistry of nutrition . 3. Edition. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8274-2041-1 , p. 491 .

- ↑ C. Hellerbrand: Clinical Management of Liver Cirrhosis . 2014, Volume 1, pp. 6-11.

- ^ JE Nestler: Sex hormone-binding globulin and risk of type 2 diabetes. In: N Engl J Med. 361 (27), Dec 31, 2009, pp. 2676-2677; author reply 2677-2678, PMID 20050388 ; Abstract available at nejm.org , accessed January 8, 2009.

- ↑ MD Zeng, JG Fan, LG Lu, YM Li, CW Chen, BY Wang, YM Mao: Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases. In: Journal of Digestive Diseases. 9, 2008, pp. 108-112. doi: 10.1111 / j.1751-2980.2008.00331.x .

- ↑ Carol M. Rumack, Stephanie R. Wilson, J. William Charboneau: Diagnostic Ultrasound. 2011, ISBN 0-323-05397-1 , p. 96.

- ↑ Classen, Diehl, Kochsieck: Internal Medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer-Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-437-42830-6 , pp. 1311-1315.

- ↑ Giorgio Bedogni, Stefano Bellentani, Lucia Miglioli, Flora Masutti, Marilena Passalacqua: The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population . In: BMC Gastroenterology . tape 6 , November 2, 2006, ISSN 1471-230X , p. 33 , doi : 10.1186 / 1471-230X-6-33 , PMID 17081293 , PMC 1636651 (free full text).

- ↑ T. Karlas, N. Garnov: Non-invasive determination of the liver fat content in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Comparison of Controlled Attenuation Parameters (CAP), 1H MR spectroscopy and In-phase / Opposed-phase MRI. In: Ultrasound in Med. 33, 2012, p. A113. doi : 10.1055 / s-0032-1322644 (currently not available)

- ↑ Johannes Weiß, Monika Rau, Andreas Geier: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease epidemiology, course, diagnosis and therapy. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 111, issue 26 from June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Claus Leitzmann , Claudia Müller, Petra Michel, Ute Brehme, Andreas Hahn: Nutrition in Prevention and Therapy: A Textbook . 3. Edition. Hippokrates-Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-8304-5325-3 , p. 510 .

- ↑ Deniz Cicek et al. a .: Pharmacy training telegram: Acetylcysteine. University of Düsseldorf, 2013, 7, 60–74.

- ^ Walter Siegenthaler , Hubert Erich Blum: Clinical Pathophysiology. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, pp. 874ff.

- ↑ Böcker, Denk, Heitz: Pathology. 2nd Edition. Urban & Fischer-Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-437-42380-0 , pp. 723-724.