Chess Turk

Turk or shortly Turk is the colloquial term for a contemporary often mechanical chess player called apparent chess robot , which in 1769 by the Austro-Hungarian court officials and mechanics Wolfgang von Kempelen designed and built. The builder gave the audience the impression that this device was playing chess on its own . In fact, a human chess player was hidden inside who was operating it. Copies of the device were used in various demonstrations and exhibitions until 1929. The later claim that Kempelen explicitly referred to his design as an androids is demonstrably false. Contemporary sources already report that Kempelen always spoke of a mechanical trick (which, however, he never disclosed).

history

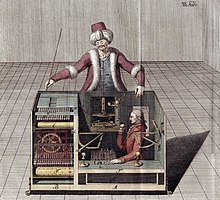

The chess machine consisted of a figure of a man dressed in traditional Turkish clothes who was sitting behind a table with a chess board. The figure played with many famous chess players of the time and mostly won. The Turk always started the game, raised his left arm, moved the chess piece and then put his arm back on a cushion. With every move the opponent made, he looked around at the board. If the move was wrong, he shook his head and corrected the position of the figure. At Gardez he nodded his head twice, at Chess three times. All movements were accompanied by a sound similar to that of a clockwork running down .

Kempelen, the inventor , who liked to show everyone who wanted to see the inside of the machine and its mechanics, stood a little to one side during the game and looked into a small box on a table. He unspokenly left open the possibility that a transmission was made by a human being to the device, but always refused to give any indication of the underlying functional principle. The viewer puzzled over a possible magnetic transmission of the train commands as well as the possibility that the machine could perform the calculations independently or at least for a section of several trains without any human intervention.

This chess machine caused a stir at the time because it was apparently the first machine that could play chess. Its inventor Kempelen was only able to ward off the many visitors by later announcing that he had destroyed the machine or that it was temporarily not operational.

Uncovering the Secret

In 1781 Kempelen demonstrated the machine to Emperor Joseph and Grand Duke Paul of Russia in Vienna . In 1783/84 he made an extensive trip to Paris, London and various German cities, where he demonstrated the mechanical chess player , but also his speech machine . In Paris, the "Turk" lost a game against François-André Danican Philidor , the world's best player at the time. According to an article in the Journal des Savants (September 1783), several scientists from the Académie française tried unsuccessfully to find out how the machine worked. In Berlin, the "Turk" is said to have played a game against Frederick the Great in 1785 and defeated him. Friedrich is said to have offered Kempelen a large sum of money to uncover the secret and, after this had happened, to have been extremely disappointed. Since then, the "Turk" is said to have stood unnoticed in a storage room in Potsdam Palace until Napoleon came there in 1806 and remembered him. He also played against the machine and lost. This version of the story is based on an article that appeared in Magazine pittoresque in 1834 and served as the basis for further articles in Le Palamède 1836 and Fraser's magazine 1839, but is believed to be inaccurate based on current research. In reality, the game against Napoleon very probably didn't take place until 1809 (after Kempelen's death) at Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna.

In 1804, the machine came into the possession of the mechanic Johann Nepomuk Mälzel , who was born in Regensburg and later lived in Vienna as a citizen , who bought it from his son after Kempelen's death and took it on long trips. Bernhard zu Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach reported that he saw the Chess Turk for the first time in Milan with Eugène de Beauharnais in 1812. He also described attending a performance at Mälzel's in New York. He came to London in 1819 and to the United States in 1826 . A number of original games have been preserved from this phase, some of which were played with specifications . A detailed biography is available in English about the machine and the time when Mälzel used it in the USA.

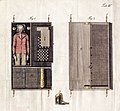

After Kempelen's visit to London, Robert Willis first showed with drawings that a person could be hidden in the machine. He described his discovery in the article "The attempt to analyze the automaton chess player" in The Edinburgh Philosophical Journal . But it wasn't until 1838 that Thournay announced in the Revue mensuelle des echécs, Vol. 1 , that people were really hidden in it. Who these helpers Kempelen were is still not fully understood, but there are reports that claim that his daughter was used for this until she fell ill. For this purpose Mälzel appointed the German Johann Baptist Allgaier , in Paris the French Boncourt and Jacques François Mouret , in London the Scots William Lewis and later the Alsatian Wilhelm Schlumberger . The often read claim that the players were short stature is demonstrably wrong.

The American writer Edgar Allan Poe also analyzed the secret of the machine and published a possible solution in his essay “Maelzel's chess player”.

Other sources report that the secret was first revealed when a spectator shouted "fire, fire" during a demonstration at a fair. Mälzel then opened the box to let the player out. Another report says that the Walker brothers, who also recreated the machine, observed how Schlumberger climbed out of the box after an event in the backyard and it was carried away sweaty on Mälzel's shoulders.

Contemporary illustrations

Title page Windisch

Whereabouts of the Chess Turk

After the death of Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, the chess Turk came into the possession of the chess-loving doctor John K. Mitchell through an intermediary. After some private demonstrations, he donated the machine to Peale's Museum in Philadelphia in 1840 . After fourteen years as an exhibit, the Turkish chess player burned in a fire in the museum on July 5, 1854.

Replicas and survival

The first real replica was made while Mälzel was traveling through America. The Walker brothers performed their American Chess Player in New York in May 1827, after Mälzel had moved on to Baltimore . After Mälzel heard about it, Mälzel traveled briefly back to New York, attended the Walkers' event and made an offer to buy their machine for $ 1,000 and give the brothers an employment contract. The brothers refused, but their demonstrations were unsuccessful in the long term, although they were only charged half the entrance fee, so they had to stop the events.

A substantially similar figure was built between 1865 and 1868 by Charles Hooper (1825-1900) of Bristol and was named Ajeeb 'The Egyptian'. The device was first shown in London until 1876 and arrived in the USA in 1885. There it was exhibited in New York's Eden Museum and was a public attraction. Its operators at demonstrations included some of the best players in the country, including Harry Nelson Pillsbury and Constant Ferdinand Burille. In 1929 it was destroyed by fire on Coney Island .

The manufacturer Charles Godfrey Gümpel built the Mephisto in 1878 . This machine, which is electromagnetic remote-controlled via cable, was operated by Isidor Gunsberg and Jean Taubenhaus , among others .

Interest in the history of the Chess Turk increased again with the advent of modern computer technology . A modern reconstruction of the Chess Turk is now part of a permanent exhibition in the Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum in Paderborn. In the Technical Museum in Vienna , visitors were able to compete against a holographic version of the Chess Turk for a while.

More than two centuries after the building of the Turk, chess computers and chess programs with "superhuman" skill levels are a reality. A chessboard with an animated 3D representation of the chess Turk has been integrated into the Fritz program since version 9 .

A possible etymological derivation of the expression "something Turk " or "build a Turk" in the sense of "just pretend something", "fake something" relates to the figure of the chess Turk, because the doll figure dressed in Turkish should and should give the impression of a machine capable of thinking long successfully awakened. The idiom is not xenophobic, but is based on a concrete experience at the time that had nothing to do with the nationality addressed. The robe was exotic and, as in many magic tricks, was only intended to distract the viewer from the actual deception. It has not been established whether this explanation has anything to do with the actual origin of the phrase and its use.

By Walter Benjamin is Turk in his thesis on the history as allegory made to the relationship between Marxism and theology:

“The puppet called ' historical materialism ' should always win . It can easily take on anyone if it takes theology into its service, which today is known to be small and ugly and is not allowed to show itself anyway. "

See also

- For Amazon Mechanical Turk , see: Amazon Web Services .

Remarks

- ^ According to newspaper reports, Johann Nepomuk Mälzel traveled to America in 1826 with almost all of his machines. See also the article Panharmonikon

Individual evidence

- ↑ Letters about the chess player of Herr von Kempelen, p. 9.

- ^ The Book of the first American Chess Congress, p. 424. Online

- ^ Journey of Sr. Highness of Duke Bernhard to Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach through North America in the years 1825 and 1826, Wilhelm Hoffmann, 1828, p. 255. Online

- ↑ The Book of the first American Chess Congress: Containing the Proceedings of that celebrated Assemblage, held in New York, in the Year 1857, By Daniel Willard Fiske, pp. 420-483. On-line

- ^ The Book of the first American Chess Congress: Containing the Proceedings of that celebrated Assemblage, held in New York, in the Year 1857, By Daniel Willard Fiske, p. 456. Online

literature

- JE Biester: Writing about the Kempel chess game and speech machines . In: Berlin monthly journal . 1784, pp. 495-514.

- Robert Löhr : The chess machine. Historical novel . Piper, Munich 2004. ISBN 3-492-04796-3 .

- Marion Faber (Ed.): The chess machine of the Baron von Kempelen . Harenberg, Dortmund 1983, ISBN 3-88379-367-1 , reprint of the edition of Joseph F. zu Racknitz: About the chess player of Mr. von Kempelen .

- Brigitte Felderer, Ernst Strouhal: Kempelen - Two machines. Texts, images and models of the speaking machine and the chess-playing android Wolfgang von Kempelens . Special number, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-85449-209-X .

- Karl F. Hindenburg: About the chess player of Mr. von Kempelen. Along with a picture and description of his speaking machine . Müller, Leipzig 1784.

- Gerald M. Levitt: The Turk, chess automaton . McFarland, Jefferson, NC 2000, ISBN 0-7864-0778-6 .

- Joseph F. zu Racknitz: About the chess player of Mr. von Kempelen and his replica . Breitkopf, Leipzig 1789.

- Tom Standage : The Turk. The story of the first chess machine and its adventurous journey around the world . BVT, Berlin 2005. ISBN 3-8333-0317-4 .

- Jiri Veselý: Wolfgang von Kempelen's most famous invention . In: Leaves for the history of technology . Volume 36/37. 1974/75, pp. 25-46.

- Robert Willis: An attempt to analyze the automation chess player of Mr. de Kempelen . Booth, London 1821.

- Karl G. von Windisch: Letters about the chess player of Herr von Kempelen, along with three copperplate engravings that introduce this famous machine . Mechel, Basel 1783.

- The resurrected von Kempelen chess machine . In: Patriotic papers for the Austrian imperial state . July 31, 1819, pp. 1-4.

- The secret of the famous chess machine. . In: The eagle . July 1, 1841, pp. 5-7.

Web links

- Treatise on the device

- Chess computer history

- The first chess computer was none ( Memento from February 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- T_Schachtuerke again awakened - information page on the reconstruction in the Paderborn HNF

- Paderborn Chess Turk Cup - International chess tournament named after the chess Turk

- Meaning of the word "turkish" (German language - questions and answers, a FAQ list from the Usenet forum de.etc.sprache.deutsch)

- Video about the Chess Turk

- Daniel Meßner and Richard Hemmer: The Chess Turk . In: Zeitsprung - Stories from History (Podcast). 15th July 2020