turkish (verb)

The verb turks is a slang term for fake, fake, often called discriminatory is felt. A contemporary word borrowed from English with a similar but not identical meaning is faken .

etymology

The origin of the verb in general or the phrase "build a Turk" in particular is unclear. Three possible origins are discussed.

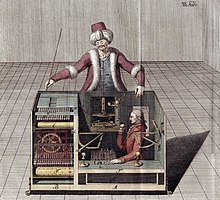

- The mechanical chess player or chess Turk , built by Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1769 , mislead an audience. Apparently - and many contemporaries believed this too - it was a chess robot with actual artificial intelligence that could play chess on its own. He performed his features through a human figure in Turkish costumes. In fact, it was a trick: a human chess player was hidden inside the machine. However, Kempelen himself never claimed that it was an android ; this attribution was only made by a third party. After Kempelen's death, Johann Nepomuk Mälzel operated the chess Turk expressly with the intention of giving the appearance of a real machine. The fraud was exposed by several contemporary authors, including Edgar Allan Poe in his essay Maelzel's Chess Player (1836).

- According to the German dictionary founded by the Brothers Grimm in 1854, the phrase "to pose a Turk" has the colloquial meaning of "to fool someone when taking a tour" from around 1900. The 1916 by the captain a. D. and Library Council of the Prussian State Library founded Walter Trans Feldt work word and custom in Germany's army and fleet gives us this further explanation: Under the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. (1840-1861) were commanders with troops tours of their associations like to hold impressive combat exercises , the sequence of which, however, had been carefully studied beforehand. Although this was extremely detrimental to the training purpose of a troop maneuver (and was therefore expressly forbidden in the drill regulations of 1906), it made the commander look good in front of the inspector. Such exercises, mutated into open-air games, were soon referred to by officers as "Turkish maneuvers" or "building a Turk". The first use of this derisive expression is attributed to Lieutenant General Gebhard von Kotze (1808-1893), who during his time as a major in the Alexander Guard Grenadier Regiment (1851-1856) often held inspection exercises with his battalion in the Tempelhof Feldmark. There was also a Turkish grave there from 1798 to 1866 (rebuilt in the Turkish cemetery in Neukölln in 1867 ), which often played an important role in the exercises and probably also gave it its name. In the course of time, the meaning seems to have generalized to the one used today (“fooling someone”). The Grimm's dictionary, however, allows another origin. There is called "Turk" u. a. the practice called a kingdom Turks help to raise in the form of a tax on alleged military campaigns against the Turks, but then not to combat an alleged Turkish threat are selfishly directed, but often, or even to the general public. The term thus had its origin in the time of the Turkish wars.

- A third thesis is the following: On the occasion of the opening of the Kiel Canal in 1895, the corresponding national anthem was played when the respective warship passed . When the Turkish ship arrived, however, the band had to improvise: In the absence of sheet music, the band played the folk tune, Good Moon, you walk so quietly because of the crescent moon in the Turkish flag .

It is conceivable that the military meaning and the meaning of “deceiving” have different origins and were later mixed up.

See also

literature

- Christoph Gutknecht: From stair jokes to pickled cucumber time. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56833-6 , pp. 28–49 ( limited preview in Google book search).

Web links

Wiktionary: build a Turk - explanations of meanings, word origins, synonyms, translations

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duden: The German orthography. Mannheim 2006, Lemma Turks

- ↑ a b c Heinz Küpper : Dictionary of everyday language. DTV, Munich 1971, Lemma Turk .

- ↑ a b Bastian Sick : How do you build a Turk? . In: Questions to the Onion Fish , Der Spiegel , August 17, 2005.

- ↑ Edgar Allan Poe: Maelzel's Chess-Player at wikisource (English)

- ↑ a b Turk , m . - Section: 2 e). combat exercise against an assumed enemy . In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm (Hrsg.): German dictionary . tape 22 : Treib – Tz - (XI, 1st section, part 2). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1952, Sp. 1848–1854 ( woerterbuchnetz.de ).

- ↑ Christoph Gutknecht: From stairs joke to pickled cucumber time. Beck, Munich 2008, pp. 45–46 ( limited preview in Google book search).