Mary Queen

Mary Queen , latin Maria Regina is a Marie titles . The veneration of Mary as Queen developed in stages in the course of the first centuries in Christian literature and art, in theology and in the piety of the faithful.

The development of the royal veneration of Mary in the first millennium

Biblical basis

At the proclamation , Mary is called to be the mother of the Son of God and King David : "The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever and his rule will not end" ( Lk 1.32-33 EU ). The later belief relates to this that Mary, as the mother of the Messiah King, shares in his royal dignity.

Early approaches (late 4th century / early 5th century)

The earliest attempts at royal veneration of Our Lady can be seen in the late 4th century in art and at the beginning of the 5th century in literature. Before the 5th century, Our Lady was depicted in simple clothes, without any courtly milieu in literature.

In the scenes of adoration by the wise men of the silver reliquary of San Nazaro Maggiore in Milan (before 382) and on a relief plate in the Musée Lavigerie in Carthage (around 430), which are modeled on an audience at the imperial court, Maria appears for the first time as a relative of the royal court of Christ. A little later there are also references to Mary's membership in the court of the Christ King in the literature. Prudentius († after 405) also draws attention to this in connection with the courtly design of the homage by the wise, while Severian von Gabala († after 408) says in the illustration of the dignity of Mary that the Holy Virgin was called to the royal castle to the to serve divine motherhood.

Queen Mother (first half of the 5th century)

During the first half of the 5th century, Our Lady was given a courtly attribute for the first time in art and literature, as Queen Mother, but not yet as Queen. Of this, too, art gives the earliest information. In the Alexandrian Chronicle of the World (392–412) she is shown with her child in her arms and like Jesus Christ in the black and red color of the precious imperial leaf purple .

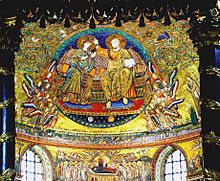

On the triumphal arch mosaics of S. Maria Maggiore in Rome (completed in 434) Mary is clothed in the golden cyclas, the court robe of the Regia Matrona and the Holy Virgin in heaven. The golden cyclas was the court costume of a queen mother or the empress, who had not yet been raised to Augusta (empress).

The literary testimonies follow soon afterwards: Hesychius of Jerusalem (+ after 450) praises the Virgin Mary as "mother of the heavenly king" and the doctor of the church Petrus Chrysologus , Metropolitan of Ravenna († approx. 450), pays homage to her as dominatrix , as "mistress." "And as Genitrix Dominatoris , as" mother of the ruler ".

The Heavenly Queen at the side of the Heavenly King (late 5th century)

It was not until the late 5th century that people began to venerate Mary as the heavenly counterpart of the earthly queen and to describe this dignity more and more precisely. Initially, she was honored in literature with names such as “heavenly queen” (Chrysippus of Jerusalem † 479) and in several Latin sermons as Domina nostra (“our mistress”), also a title of the empress.

It remained open until the second half of the 6th century which ideas were associated with these designations. Only then was the literary picture of Regina Maria completed. Now the ideas of the Kingdom of Mary were interpreted. The earliest evidence comes from writings from the imperial city of Constantinople and relates the kingdom of Mary to the Byzantine emperor, his rulership tasks and the internal and external protection of the empire. The climax in the interpretation of the royal dignity of Mary is the Carmen in laudem sanctae Mariae by Venantius Fortunatus († around 600), written in the imperial city of Ravenna. According to this, the kingdom of Mary extends over heaven, earth and the underworld with its inhabitants, i.e. over the entire cosmos. The mother of Jesus Christ does not rule independently, but by the side of her Son, the almighty, heavenly King, and is subject to him. The sign of this is that she received the imperial insignia and her official dress from him, and he let her sit on his throne.

In the fine arts, a new type of image of Mary arose in this milieu at the beginning of the 6th century, which is based on the late antique image of the enthroned Byzantine imperial couple. Like the empress to the emperor, Maria is enthroned on her own precious stone throne next to her son, is decorated like the heavenly king with an imperial nimbus , surrounded by angels and wrapped in purple robes, in the leaf-purple stole with palla .

The Mother of God appears at the side of her Son, the heavenly King. like the empress in the Byzantine Empire at the side of her husband. However, despite the proximity to the imperial image, the distance to it must not be overlooked. It is expressed in the renunciation of the heavenly majesties on the most important insignia of the Empress and the Emperor:

- the imperial diadem

- the imperial official costumes ( purple lamys and the imperial triumphal trabea ) as well

- the gem-studded shoes

These differences are intended to draw attention to the fact that the kingship of Jesus Christ and Mary is of a different nature from earthly rulership, and that Christ and his Mother are not rulers of this world, but heavenly majesties.

This image of the Queen of Mary on the gemstone throne and in this purple dress remained the defining image of the Queen of Mary in the west and east for the next centuries. In the course of time, Mary's kingship is explained in more detail through further royal insignia (wreath from the hand of God and the celestial globe), which are presented to her, but also through the various iconographic additions (angels, apostles, saints, bishops as representatives of the church) with their specific tasks in the kingdom of Christ.

The Queen of Space at her son's side (during the 6th century)

This theme is tangible in the visual arts earlier than in literature. On an ivory diptych in the Bode Museum in Berlin (between 520 and 550) and on the apse mosaic of Panagia Angeloktistos in Kiti on Cyprus (more likely 7th century) a celestial globe indicates the rule over the cosmos. On the ivory diptych, the mother of Jesus is enthroned like the Empress Theodora on her mosaic in S. Vitale in Ravenna under a shell-shaped apse, in the spandrels the moon and sun are attached, the symbols of cosmic rule, and the cosmic globe is held by one of the two angels , presented on the apse mosaic by two angels to the child and his mother. Because Mary gave birth to the Pantocrator, the ruler of all, Christ, she participates in his rule over the universe. She wears her traditional costume as a queen, so no imperial costume.

Maria Augusta (Empress) (2nd half of the 6th century)

It signified a change in the representation of Maria Regina when at the time of Empress Sophia, the wife of Justin II (565-578) Maria and her son on the wall of a Byzantine official building on the ramp to the imperial palace on the Roman Palatine with the Jeweled diadem and depicted in the triumphal trabea of a Byzantine empress sitting on an imperial lyric throne. Two angels pay homage to them with a golden crown in their hands.

The heavenly queen was made empress of the Eastern Roman Empire, and she was associated with government, unity and the welfare of the state. It seems conceivable that this picture of Maria Empress, after the victory of the Byzantines over the Ostrogoths and the reintegration of Rome into the Byzantine Empire, had the task of connecting ancient Rome with the new Rome and its imperial family and strengthening this connection. The politicization of the Queen of Mary image could indicate that it was later made to disappear when the official building was converted into a church.

This tendency to politicize the image of Mary found a climax in the image of Mary as empress in a Byzantine chapel in the amphitheater of Durres (Albania, before 630).

Maria in the jeweled diadem and the triumphal trabea of the empress carries the victory sign of the Christianized Victoria, the cross of Christ, in her right hand and the celestial globe with the signs of the zodiac and the sun in her left. The heavenly empress is the personified power of Christ and ruler over the cosmos and peace-bringer. The original type of this picture seems to have originated there in the context of the tremendous victory of the Byzantines over Avars and Slavs in 626 before Constantinople, i.e. after 626. In Dyrrachium, which is surrounded and threatened by Slavs, the image of the heavenly empress is intended to strengthen trust in the power of victory and peace of Mary.

This image of the Maria Empress in the jeweled diadem and the official costume of Augusta, together with the Maria Augusta image in Rome, remained an exception in the iconography of the Queen of Mary.

Holy Virgin and Queen (from the 8th century at the latest)

A special variant of the image of the Virgin Mary, which up to the twelfth century could only be found in the city of Rome, is the image of the Blessed Virgin and Queen Mary. Its characteristic attribute is the Cyclas of the Consecrated Virgin in Heaven, known from S. Maria Maggiore in Rome. Mary also carries them on the reliquary of Grado (6th century), the next example. She is enthroned with her son on the imperial lyric throne, decorated with an imperial nimbus and the scepter of the cross, but without an imperial jewel diadem. This does not appear until the beginning of the 8th century on the Marian icon of the Madonna della Clemenza in Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome. The kingship of Mary is made particularly visible through the jewel diadem, but also her consecrated virginity through the Cyclas, which is adorned with pearls and precious stones as a sign of royal dignity. The peculiarity of this portrait is that parallels to the Byzantine empress image are avoided. Maria does not wear a Byzantine Augusta diadem or the official costume of an Augusta. This type of image was evidently created in the vicinity of the papacy. The popes probably wanted to demonstrate their independence from the Byzantine rulers through the uniqueness of their image of the Queen of Mary, which is evident in the distance to the insignia of Augusta. H. Belting writes that Mary had been the real sovereign of Rome and the Pope her deputy since John VII (705–707).

Possible factors for the emergence of royal veneration of Mary

The idea of honoring the mother of Jesus with royal dignity was probably influenced by the glorification of Christ that began in the early Byzantine period. This was inspired by the teaching of the Council of Nikaia (325) about the essential equality of the Son of God with God the Father and the christological foundation of the Christian empire. On this basis, Christ was not only awarded the title of emperor, but his life and all areas of life were viewed from an imperial perspective. The life of Christ was portrayed as the life of an emperor, heaven as an imperial city with the throne room in which Christ is enthroned on the imperial throne surrounded by angels. In this setting the angels became assistants to the throne, the apostles and martyrs became court officials and the heavenly magistrate. In this environment, the task of giving the mother of the heavenly king an appropriate court rank and dignity arose as if by itself. For her, the title “Queen Mother” with the corresponding marks of honor was probably a matter of course. Especially since, according to an imperial law of the 5th century, female members of public officials, but only his wife and mother, were allowed to wear clothes and sediles corresponding to the official.

The Regina Maria and the pagan heavenly queens

The worship of Mary as Queen of Heaven developed in a world of paganism. This was shaped by the cult of the heavenly queens of various religions. The goddess Tanit was worshiped as the “Queen of Heaven” in large areas of the Roman Empire, coming from the Arab-Canaanite region, the most widespread was probably the cult of the Egyptian goddess Isis, who was called Regina caeli and finally the goddess Juno.

In view of the cake offering by the Arab Kollyridians to Maria, which is reminiscent of the Tanit cult, it was considered whether the Marian title "Regina caeli" might not derive from there. The only sporadic attestation to this title of the Tanit and also in exclusive circles offers a basis that is probably too narrow for this derivation compared to the worldwide spread of the veneration of Mary as “Regina caeli” in the ecclesiastical world of faith. In addition, there is no iconographic evidence for this thesis. The same arguments apart from the exclusivity would also speak against a derivation from the Isis cult. Since 395 the pagan cults and thus also the Isis religion were banned from the public of the Roman Empire and thus probably also excluded a decisive influence.

According to Apocalypse 12, women clad with the sun, the moon at their feet, with twelve stars around their heads, refer to the goddess Juno as their origin. She was represented as Regina caeli with a wreath of twelve jewels on her head. This text has been related not only to the Church but also to the Mother of Jesus Christ since the 5th century. This interpretation did not necessarily have to be based on the cult of Juno, but was explained by the superior position of the mother of Jesus since the Council of Ephesus (431) and her powerful position as Regina caeli. Of course, the religious aura in the public of late antiquity was not free from the memory of the powerful pagan goddesses, their titles and their stories. Some of them may well have been felt to be correct for the mother of Jesus and could therefore have helped shape the image of the kingdom of Mary. But the kingship of this pagan goddess was fundamentally different from that of Mary: As the highest goddesses, they were omnipotent rulers.

Adoration of Mary as Queen in the second millennium

The intensification of this cult

The veneration of Mary as Queen continued to be cultivated with increased intensity in the second millennium, especially in the West. The image of the crowned Queen of Heaven became the predominant type of image of Mary in the West in the high Middle Ages.

In the following centuries further emblems were added to it, around 1180 in Spain the lion on the throne of Mary, referring to King Solomon. The lion throne alludes to Mary's wisdom and royal descent. At the time of the Counter-Reformation , the image of the Madonna standing on a crescent moon was given further attributes: the heavenly queen wears a crown on her head, the scepter in her right hand, the blessing child or the globe on her left arm.

In the piety of the Middle Ages, the kingship of Mary relates more to the power of her intercession, a royal prerogative that originated in the right of the king to protect the needy. From Paris, after the naval battle of Lepanto (1571), a new image of the queen spread: the image of Mary as Queen of Peace. In the course of the democratic currents of the 20th century, the image and veneration of Mary as Queen lost its radiance and spread.

The Maria-Queen-Feast

In the 19th century, individual religious orders and dioceses began to celebrate the feasts of the Queen of Mary, for example in Ancona in 1845 in honor of the Queen of All Saints, as well as in Spain and in some dioceses in Latin America in 1870 . Pope Pius XII At the end of the Marian Year 1954, with the encyclical Ad caeli reginam, put the Queen of Ideas festival for the Church as a whole on May 31. The general Roman calendar in 1969 moved the festival to August 22nd, the octave day of the Feast of the Assumption , to which it is internally related. The Day of Remembrance of the Immaculate Heart of Mary , previously celebrated on August 22, was set on the day after the solemnity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus .

Patronage and patronage

- Churches: see Maria-Königin-Kirche , Maria-Rosenkranzkönigin-Kirche

- Missionary Sisters Queen of the Apostles in Vienna

- Baptismal name: see Regina (first name)

Invocations in the Litany of Loreto

The Lauretan Litany contains the following invocations to Mary as Queen:

- Queen of Angels ( Regina angelorum , August 2nd)

- Queen of the Patriarchs ( Regina patriarcharum )

- Queen of the Prophets ( Regina prophetarum )

- Queen of the Apostles ( Regina Apostolorum , September 5)

- Queen of the Martyrs ( Regina martyrum )

- Queen of Confessors ( Regina confessorum )

- Queen of the Virgins ( Regina virginum )

- Queen of All Saints ( Regina sanctorum omnium , May 31)

- Queen received without original sin ( Regina sine labe originali concepta , December 8th)

- Queen taken to heaven ( Regina in caelum assumpta , August 15)

- Queen of the Holy Rosary ( Regina sacratissimi rosarii , October 7th, Rosary Festival )

- Queen of families (Regina familiarum)

literature

- Elmar Fastenrath and Friederike Tschochner: The Kingdom of Mary. In: Remigius Bäumer , Leo Scheffczyk (Hrsg.): Marienlexikon. Volume 3, St. Ottilien 1991, pp. 589-593 (Fastenrath. Literature), 593-596 (Tschochner, Art History) ISBN 3-88096-893-4 .

- Wolfgang Fauth: Queen of Heaven . In: Ernst Dassmann (Ed.), Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity. Vol. 15, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1991, Col. 226-233.

- Christa Ihm: The Programs of Christian Apse Painting from the Fourth Century to the Middle of the Eighth Century. 2nd edition, Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1992, pp. 55-68.

- Engelbert Kirschbaum (Ed.): Lexicon of Christian Iconography. 3rd volume, Freiburg i. Br. 1971, Sp. 157-161.

- Gerhard Steigerwald: The Kingdom of Mary in Literature and Art of the First Six Centuries. Freiburg i. Br. 1965 (typed theological dissertation).

- Gerhard Steigerwald: Purple robes of biblical and ecclesiastical persons as carriers of meaning in early Christian art. Bonn 1999 = Hereditas. Studies on Ancient Church History 16, pp. 69–147.

photos

Maria Coronation Altar, Altenberg Cathedral (15th century): Coronation of Mary by the Most Holy Trinity

Trinitarian Coronation of Mary in the altarpiece of the Marienkirche in Wittstock ( Claus Berg , around 1530)

Individual evidence

- ^ WF Volbach: Early Christian Art . Hirmer-Verlag, Munich 1958, plate 112 .

- ^ J. Kollwitz: Eastern Roman sculpture of the Theodosian time . In: Studies on late antique art history . tape 12 . Berlin / Leipzig 1941, p. 181–184 plate 53 .

- ↑ Gerhard Steigerwald: The Kingship of Mary in the literature of the first six centuries . In: Marianum . tape 37 , 1975, pp. 17th f .

- ↑ R. Sörries: Christian antique book illumination at a glance . Wiesbaden 1993, plate 46, VIID and E verso .

- ↑ J. Wilpert / WN Schumacher: The Roman mosaics and church buildings from the 4th to the 13th century . Freiburg i.Br. 1976, p. 317 Pl. 61–63 .

- ↑ Gerhard Steigerwald: The Kingship of Mary in the literature of the first six centuries . In: Marianum . tape 37 , 1975, pp. 19-22 .

- ↑ Gerhard Steigerwald: The Kingship of Mary in the literature of the first six centuries . In: Marianum . tape 37 , 1975, pp. 26-29 .

- ↑ Gerhard Steigerwald: The Kingship of Mary in the literature of the first six centuries . In: Marianum . tape 37 , 1975, pp. 36-38 .

- ↑ Gerhard Steigerwald: The Kingship of Mary in the literature of the first six centuries . In: Marianum . tape 37 , 1975, pp. 39-47 .

- ^ W. Hahn: Moneta imperii byzantini . In: Austrian Academy of Sciences (Hrsg.): Publications of the Numismatic Commission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences . tape 4 . Vienna 1975, plate 5,50b (Follis (copper coin) Emperor Justin II and Empress Sophia).

- ^ FW Deichmann: Early Christian buildings and mosaics from Ravenna . Wiesbaden 1958, plates 112, 113 (example: Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, Maria Regina Throne (plate 112) and Christ Throne (plate 113)).

- ^ Gerhard Steigerwald: Purple robes of biblical and ecclesiastical persons as carriers of meaning in early Christian art . In: Hereditas. Studies on the Ancient Church History . tape 16 . Borengässer, Bonn 1999, p. 83 f .

- ^ Wolfgang Fritz Volbach: Ivory works of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages . 3. Edition. Mainz 1976, p. 91 No. 137 plate 71 .

- ↑ André Grabar : The art in the age of Justinian from the death of Theodosius I to the advance of Islam . Munich 1967, fig. 144 .

- ↑ M. Andaloro: Santa Maria Antiqua tra Roma e Bisanzio . Milano 2016, p. 154-159 with pictures .

- ^ Gerhard Steigerwald: Purple robes of biblical and ecclesiastical persons as carriers of meaning in early Christian art . In: Ernst Dassmann and Hermann-Josef Vogt (eds.): Hereditas. Studies on the Ancient Church History . tape 16 . Bonn 1999, p. 123-133 .

- ^ B. Brenk: Papal Patronage in a Greek Church in Rome . In: J. Osborne, JR Brandt, G. Motganti (eds.): Santa Maria Antiqua al Foro Romano cento anni dopo. Atti del Colloquio internazionale Roma, 5-6 maggio 2000 . Rome 2004, p. 68, 74 .

- ↑ Maria Andaloro: I mosaici parietali di Durazzo o dell 'origine constanopolitana del tema Iconográfico di Maria regina . In: O. Feld and U. Peschlow (ed.): Studies on late antique and Byzantine art dedicated to FW Deichmann . tape 3 . Bonn 1986, p. 103-112 plates 36,1-3 .

- ^ Gerhard Steigerwald: Purple robes of biblical and ecclesiastical persons as carriers of meaning in early Christian art . In: Ernst Dassmann, Hermann-Josef Vogt (Ed.): Hereditas. Studies on the Ancient Church History . tape 16 . Bonn 1999, p. 133-143 .

- ↑ A. Grabar: The art in the age of Justinian from the death of Theodosius I to the advance of Islam . Munich 1967, ill.358 .

- ^ H. Belting: Image and cult. A history of the image before the age of art . 3rd unchanged edition. Munich 1993, p. 143–148 color plate. II .

- ^ Gerhard Steigerwald: Purple robes of biblical and ecclesiastical persons as carriers of meaning in early Christian art . In: Ernst Dassmann, Hermann-Josef Vogt (Ed.): Hereditas. Studies on the Ancient Church History . Bonn 1999, p. 118 .

- ^ H. Belting: A private chapel in medieval Rome . In: Dumbarton Oaks Papers . tape 41 , 1987, pp. 57 .

- ↑ J. Kollwitz: Christ Basileus . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . tape 2 , 1954, p. 1257-1262 .

- ↑ R. Delbrueck: The Consulardiptychen and related monuments . In: Studies on late antique art history . tape 2 . Berlin / Leipzig 1929, pp. 55 .

- ^ W. Fauth: Queen of Heaven . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . tape 15 . Stuttgart 1991, Sp. 226-233 .

- ↑ GM Alberelli: L 'eresia dei collyridiani e il culto paleocristiano di Maria . In: Marianum . tape 3 , 1941, pp. 187-191 .

- ^ WH Roscher: Isis . In: Extensive encyclopedia of Greek and Roman mythology . tape 2/1 . Leipzig 1890, Sp. 360-548 .

- ^ M. Errington: Christian accounts of the religious legislation of Theodosius I. In: Klio . No. 79 , 1997, pp. 398-443 .

- ^ W. Fauth: Queen of Heaven . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . tape 15 . Stuttgart 1991, Sp. 228 .

- ↑ a b Friederike Tschochner: The Kingship of Mary in Art . In: Marienlexikon . tape 3 . St. Ottilien 1991, p. 594 to 596 .

- ↑ www.kirchenweb.at: Mariä Königin Lexikon - Holy Mary Mother of God. Retrieved November 5, 2017 .

- ↑ Ad caeli reginam . Holy See. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ↑ www.katholische-kirche-steiermark.at: Deanery Feldbach - Catholic Church Styria. Diocese of Graz-Seckau / Catholic Church of Styria, accessed on November 5, 2017 (patronage information in the info box).