Matthäus Hipp

Matthäus Hipp incorrectly also Matthias od. Mathias (born October 25, 1813 in Blaubeuren ; † May 3, 1893 in Fluntern ) was a German watchmaker and inventor who lived in Switzerland . His most important, long-lasting inventions were electric looms , railway signals and pendulum clocks as well as the Hipp'sche band chronograph .

Life

The monastery miller's son was born on October 25, 1813 in Blaubeuren ( Württemberg ). As an eight-year-old child he had an accident while climbing one of the many rocks there and was disabled for the rest of his life. At 16, he came to a watchmaker Johan Eichenhofer in Blaubeuren in the teaching . After completing his apprenticeship, the years of traveling followed : 1832 to watchmaker Valentin Stoss in Ulm, 1834 he worked in St. Gallen , then between 1835 and 1837 in the watch factory Savoie in St. Aubin on Lake Neuchâtel .

In 1840 he moved to Reutlingen and opened his own workshop there in 1841 at the age of 28. In the same year he married the teacher's daughter Johanna Plieninger. The couple had four children.

After the suppressed revolution in Baden in 1849, his application as director of the watchmaking school in Furtwangen was rejected for political reasons, as he was considered a democrat . As a result, Hipp decided to leave Germany in 1852. He was appointed head of the national telegraph workshop and technical director of the telegraph administration by the Swiss government. When he was hired, he had express permission to continue working privately, but when the income from inventor activity by far exceeded his official salaries, conflicts with the administration and parliament were inevitable. Hipp therefore drew the consequences in 1860 and asked for his discharge from the Swiss civil service.

The next section of his life took him from Bern to Neuchâtel , where he took over the management of a newly built telegraph factory. It was not until 1889 that Hipp retired from the company's management and handed over management of the company to the engineers Albert Favarger and A. De Peyer. From then on, until 1908, the brands bore the signature “Peyer & Favarger, Succ. de M. Hipp ".

Immediately afterwards he moved to Fluntern near Zurich to live with his daughter. On May 3, 1893, Matthäus Hipp died in Fluntern at the age of 80. His wife survived him by four years.

Matthäus Hipp, who had lived and worked in Switzerland since 1852 but had never given up his German citizenship, was given the honorable nickname “The Swiss Edison”.

Services

In the course of 40 years, Matthäus Hipp brought more than 20 inventions to technical maturity. Some of his inventions turned out to be so good that they could be manufactured and sold for about a hundred years without any fundamental changes.

- 1843 Description of a pendulum clock with mechanical pallet escapement

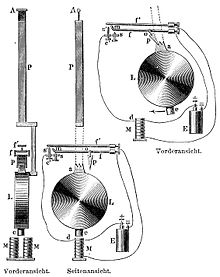

- 1847 chronoscope

- 1854 counter-telegraphing on the same line

- 1855 Electric loom

- In 1856 he laid a cable of his own construction through Lake Lucerne to Flüelen

- 1862 Hippsche turning disc , an automatic visual railway signal

- In 1862 he installed a clock system with master clock and slave clocks in Geneva

- 1863 On May 27th he receives a French patent for the electric drive of pendulum clocks, the "Hippsche Wippe"

- In 1866 he and Frédéric-William Dubois developed an electric registration chronograph with a marine chronometer

- 1867 electric piano

- In 1874 he delivered a special chronograph to Vienna for observing nerve activity

- 1881 high-precision electric observatory clock for the Neuchâtel observatory

- 1889 registering speedometers

Awards

- 1840 Annual Technical Prize from the Württemberg Central Office of the Agricultural Association "for its new, ingenious principle in clockmaking to achieve a uniform pendulum walk"

- 1873 Knight's Cross of the Austrian Franz Joseph Order

- 1875 honorary doctorate (Dr. phil. E. h.) From the University of Zurich .

literature

- Hans Rudolf Schmid: Hipp, Matthäus. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , p. 199 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Anne-Françoise Schaller-Jeanneret: Hipp, Matthias. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- R. Wolf : Notes on Switzerland. Kulturgeschichte 470. In: Quarterly publication of the Natural Research Society in Zurich / ed. by Ferdinand Rudio 39 (1894), pp. 365-374 ( digitized version ).

- R. Weber, L. Favre: Matthäus Hipp: 1813-1893 . Bulletin de la Société des Sciences Naturelles de Neuchâtel, Volume 24 (1895-1896), p. 212f e-periodica.ch

- Helmut Kahlert: Matthäus Hipp in Reutlingen. Years of development of a great inventor (1813–1893) . In: Journal for Württemberg State History, Vol. 48, 1989, pp. 291–303. Also in: Chronométrophilia No. 76, 2014, pp. 53–66.

- K. Jäger, F. Heilbronner (Ed.): Lexicon of Electrical Engineers , VDE Verlag, 2nd edition from 2010, Berlin / Offenbach, ISBN 978-3-8007-2903-6 , p. 195

Web links

- City of Blaubeuren: Famous People

- Article by / about Matthäus Hipp in the Polytechnisches Journal

Individual evidence

-

↑ Dr. Matthäus Hipp. In: Curt Dietzschold : The Cornelius Nepos the watchmaker. Krems ad Donau 1910, p. 51 f .; 2nd, presumably edition 1911.

Jürgen Abeler: Master of the art of watchmaking. Wuppertal 1977, p. 281. - ^ Helmut Kahlert: Matthäus Hipp in Reutlingen. Years of development of a great inventor (1813–1893). In: Journal for Württemberg State History, Vol. 48, 1989, pp. 291–303. Also in: Chronométrophilia No. 76, 2014, pp. 53–66, here. P. 60.

-

↑ Oelschläger: The Hipp'sche Chronoskop, for measuring the time of fall of a body and for experiments on the speed of shotgun bullets, etc. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 114, 1849, pp. 255-259. Caspar Clemens Mierau: Matthias Hipp and the "Hipp'sche Chronoskop" . Semester paper at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar in the course media culture, winter semester 2001/2002, accessed on April 26, 2018. Thomas Schraven: The Hipp Chronoscope . In: "The Virtual Laboratory: Essays and Resources on the Experimentalization of Life" by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin, ISSN 1866-4784 , March 30, 2004, accessed on April 26, 2018 (PDF 2.81 MB ).

- ↑ Johannes Graf: The long way to the Hipp-Wippe. When will Matthäus Hipp's clocks be electrically powered? In: Chronomètrophilia No. 76, 2014, pp. 67–77, here p. 73.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hipp, Matthew |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hipp, Matthias; Hipp, Mathias |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German watchmaker and inventor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 25, 1813 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Blaubeuren |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 3, 1893 |

| Place of death | Whisper |