Minoan religion

The religion of the Minoan culture of Bronze Age Crete is largely only known from archaeological finds.

Religion of the pre-palace period

In the pre-palace period (Early Minoan I to Middle Minoan IA, Early Minoan Period from approx. 2600 to 1900 BC) there were paved places near Tholos graves . These could have been used in connection with the cult of the dead or for religious festivals. Other sanctuaries existed both inside and outside built-up areas. Summit sanctuaries (e.g. on Mount Giouchtas ) and sacred caves (e.g. the Psychro Cave , the Kamares Cave and the Eileithyia Cave in Amnissos ) seem to have existed and were probably used for communal worship, while shrines ( e.g. in Myrtos-Fournou Korifi ) private cult practices were used. Mountains were probably the preferred abode of the gods, so that sanctuaries were built and religious festivals were celebrated there. The holy area was often delimited by a wall. Within the holy area there was an altar, more rarely a small temple. Votive offerings were placed in crevices in the rock or burned in bonfires. These votive offerings were burnt clay figurines, including people praying, body parts to ask for healing, animals (bulls, sheep, goats, pigs, dogs, birds, scarabs, rarely weasels) to ask for protection for the cattle, scarabs probably symbolically, and field crops to ask for a good harvest. The deities appear to have been deities of nature, and isolated differences in sacrificial practices suggest a polytheistic religion.

Religion of the early palace period

In the early palace period (Middle Minoan IB and II, Middle Minoan period from approx. 1900 to 1600 BC), summit sanctuaries and holy caves were used in rural regions, but in cities mostly rooms within the palaces and houses, rarely also free-standing buildings . The summit sanctuaries, of which there were at least 37, experienced their greatest heyday in the early palace period. The summit sanctuaries had special connections to the nearby palaces, such as the Giouchtas mountain to Knossos , the Traostalos mountain to Zakros , the Profitis Ilias mountain to Mallia and the Kamares cave to Phaistos. The Kamares Cave was one of around 35 sacred caves. Pottery , mostly filled with grain, was sacrificed mainly in the caves, but more rarely also on the summit shrines . B. the Kamares ceramics in the eponymous Kamares cave. A well-preserved early palace sanctuary was found in the west courtyard of the old palace of Phaistos. The sanctuary consisted of three rooms. In the first room there were benches with holes and spouts for animal sacrifices, in the second room there was a stone mortar for grain offerings, while in the third room there was a clam and a bull-headed sacrificial table. Rooms from the early palace period, known as lustral basins or adyton , were sunk into the floor, had a paved or plastered floor and could only be reached by stairs. They served sacred acts as well as open courtyards. The only known free-standing temple of the early palace period was found in Mallia. On the slope of Mount Giouchtas in Anemospilia there was another three-room temple in which a human sacrifice was carried out, which was preserved by an earthquake.

Late palace-era religion

In the late palace period (Middle Minoan II to the first half of the Late Minoan IB, Late Minoan period, from approx. 1600 to 1450 BC) numerous small summit sanctuaries were no longer used, but a few larger summit sanctuaries were expanded. The religious acts shifted to the palaces and palace-related summit shrines. Mount Giouchtas was connected to Knossos by a road. A building was erected outside the surrounding wall, inside megalithic terraces were laid out around an altar with intense scorch marks. The ordinances were performed outdoors near a crevice. There were also statuettes, libation tables, seal stones and votive tools made of bronze. The sacred caves continued to be heavily visited, e.g. But also some new ones. The Psychro Cave, also known as the Dictean Grotto, and the Ida Cave contained a particularly large number of votive offerings. Both caves were considered the birthplaces of Zeus in later Greek mythology . Other sanctuaries were located in palaces and in private houses. The ceremonies taking place in the palace were either secret or not directly accessible to most of the population. So could z. B. the throne room in Knossos was used for an " epiphany ceremony " with the appearance of a priestess disguised as a goddess, including sacrifice in the adjacent lustral basin. Other cult rites depicted on seals and seal impressions were ecstatic dances, shaking trees and hugging large stones.

Religion of the time of the last palaces

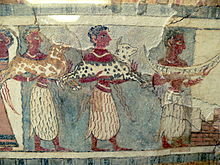

In the period of the last palaces (second half of Late Minoan IB to Late Minoan IIIA1) the Olympian gods were introduced to Crete by Mycenaean Greeks from the mainland. Nevertheless, the religious legacies remained typically Minoan. Knossos, the only palace still in use and the center of Mycenaean rule, was believed to have worshiped the Olympian gods, while the Minoan population continued to worship their ancient gods. The sarcophagus of Agia Triada gives a picture of the cult activities of that time. It shows how a dead person receives grave goods in his grave. A woman pours a liquid, maybe blood, into a kettle that hangs between two double axes. A woman carries buckets on a pole. Two men play the lyre and the double flute . Several women sacrifice a bull and goats. Blood from the bull's throat runs into a rhyton . A woman offers fruit at an altar between double axes near a temple with cult horns.

Religion of the post-palace period

In the post-palace period (Late Minoan IIIA2 to IIIC) figures of the "goddess with raised arms" were placed in shrines. They were a typical Cretan phenomenon and had strong Minoan features. In the destroyed palace of Knossos, which was probably considered sacred, there was a post-palace shrine with such figures. Even in the "refugee settlements" of the Cretan mountains in the 12th century BC Chr. Still found themselves such idols.

Minoan deities

Sometimes the view prevails that the Minoans did not know any anthropomorphic deities. Symbols for deities that appear on seals and seal prints are birds, butterflies, cocoons, double axes and sacred knots. However, there are also small, floating, mostly female persons or men and women in commanding gestures who can be viewed as gods. They wear the usual clothing of the Minoans. Previously, the theory existed that the Minoans had a Great Mother or Great Goddess who was accompanied by a youthful male god. This is now considered unlikely, although there is no rebuttal. In general, a polytheistic religion is assumed.

Deities handed down iconographically

Iconographic representations of deities can mostly be found on seals or seal impressions, but also on frescoes or in the form of faience statuettes. The areas of responsibility of these deities can be interpreted using the images and comparisons with contemporary or later cultures.

| Type deity | tasks | presentation | Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lord of the Animals | Lord of the Animals | youthful, accompanied by animals (lions, birds), subjugating animals (lions, bulls) | |

| Mistress of the animals | Mistress of nature; Mistress of the animals of the earth, the sea and the sky | accompanied by various animals (lions, monkeys, griffins , snakes, fish, dolphins and birds); sometimes portrayed as a bird woman | |

| Moon god | Moon, son of the sun goddess | standing god with moon over his head | Crescent moon |

| Snake goddess | Earth, underworld | wrapped in snakes or holding up snakes, variation of the mistress of animals | snakes |

| Sea monsters | ocean | lion-like head | |

| Sun goddess | Sun, underworld, mother goddess, queen of gods, patroness of the Minoan king | seated goddess with curvy body shapes, some with the sun over her head | Double ax, sun disk, rosette, half rosette |

| Bull of heaven | Bearer of the sun / stars | Bull's head with a shining star or a double ax between the horns | |

| Weather god | Weather, storms, son of the sun goddess, warlike god | Standing, muscular and youthful god, often armed (with spear, bow, shield), commanding gestures, clad in a short apron, sometimes a high and pointed tiara on his head, defeating enemies or beasts |

The Lord of the Animals, the Lady of the Animals and the snake goddess, whose authenticity is controversial based on the results of the radiocarbon dating ( 14 C dating), are certain types of Minoan gods, whose specific areas of responsibility either seem to be already indicated in the depictions or carefully developed using these representations.

The other deities are Nanno Marinatos' interpretation of a variety of Minoan representation types of deities, which are compared with each other and with examples of contemporary cultures.

The sun goddess is derived from the frequently depicted figure of a seated goddess with mature, maternal body shapes. The function of the goddess as mother goddess is based on her maternal form, her task as queen of the gods from the enthroned appearance. The association of the goddess with the sun on the one hand and the underworld on the other arises from the fact that the seated goddess is often associated with symbols of Minoan art, which Marinatos interprets as solar symbols (sun disk, rosette, half rosette) or symbols of the nocturnal, subterranean sun (double ax). The sun goddess is considered the patroness of the Minoan king, because on the one hand her attributes are widespread in the Minoan palaces and on the other hand the kings of contemporary cultures were also often protégés of the sun deity.

The moon god is derived from the association of a male deity with the moon symbol. According to Marinatos, both he and the weather god are considered sons of the sun goddess, since a young, partly combative, partly associated with the crescent moon is often depicted in contrast to the seated maternal sun goddess.

The weather god is inferred from various representations of a young, combative god in Minoan art as well as from the parallelism of these depictions with ancient oriental myths (such as the young, combative weather god Baal from Ugarit ), in which the young weather god fights and fights the enemies of the divine order defeated.

The sea monster as the main enemy of the weather god is revealed on the basis of a single Minoan seal imprint and corresponding ancient oriental and ancient Egyptian myths.

Finally, the bull of heaven is assumed by Marinatos on the basis of Minoan bull head representations with objects interpreted as heavenly bodies between the horns (star, double ax) and by comparisons with the sun bull of ancient Egyptian mythology .

Deities handed down in writing

Minoan deities can be handed down in writing in various ways. They are derived from Minoan Linear A texts, mentioned in Linear B texts from Mycenaean rule on Crete or, more rarely, passed down in Egyptian papyri.

| Name deity | Spelling Linear A | Spelling Linear B | ancient Egyptian spelling | tasks | Equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ameja / Amija | A-MA ? | a-me-yes ?, a-me-a ? | 'am-ᶜ-j-3 | God of healing | |

| A-sa-sa-ra | A-SA-SA-RA | Sun goddess? | Snake Goddess , Athirat | ||

| Daidalos (name pre-Greek ; recorded in Linear B in the shrine name Daidaleion) | da-da-re-jo | Daidalos | |||

| Eleuthia (name pre-Greek) | e-re-u-ti-yes | birth | Eileithyia | ||

| Totality of the gods ( Greek name : Pansi Thehoi) | pa-si-te-oi | ||||

| Ma-ri-ne-u | ma-ri-ne-u | ||||

| Pa-sa-yes | pa-sa-yes | ||||

| Pi-pi-tu-na | pi-pi-tu-na | ||||

| Po-ro-de-qo-no | po-ro-de-qo-no | ||||

| Mistress (Potnia) of the labyrinth (name Greek-pre-Greek mixed formation) | da-pu 2 -ri-to-jo po-ti-ni-ja | Mistress of the labyrinth | Ariadne ? | ||

| Priestess of the Winds (Greek name: Anemon Hiereia) | a-ne-mo-i-je-re-yes | ||||

| … -] qe-sa-ma-qa | … -] qe-sa-ma-qa | ||||

| Ratjaja / Ratjija | RA2-TI ? | r-ṯ3-jj | God of healing | possibly as r-p3-jj , Egypt. read "my healer". | |

| Si-yes-ma-to | si-ja-ma-to | ||||

| Zeus Diktaios (name Greek-pre-Greek mixed formation: Diktaioi Diwei, dative ) | di-ka-ta-jo di-we | God of the mountain Dikte , youthful dying Zeus of Crete | Zeus |

The goddess A-sa-sa-ra has only come down to us in Linear A texts. It has been suggested that her name is a spelling of the name of the ancient oriental goddess Athirat.

The healing gods Amea / Amija and Ratjaja / Ratjija were handed down from Egypt in a medical papyrus ( Medicine Papyrus, London BM 10059 , No. 32 & 33), which lists incantations in the Cretan / Minoan language ( m ḏd nf K3ftjw ) in hieroglyphic script , which are supposed to help against the " Asian ( '3m.w ) disease " (No. 32) and the " Samuna ( s3-m-ᶜ-wn-3 ) disease" (No. 33). In the second incantation the "God" ( nṯr ) Ameja / Amija and the "great God" ( nṯr p3-3 wr ) Ratjaja / Ratjija are invoked. Your possible evidence in Linear A and Linear B texts can therefore only be provided secondary.

All other traditional deities come from Linear B texts from the Mycenaean rule in Knossos. Partly pre-Greek forms of name are clearly recognizable, partly Greek name forms have been handed down, which, however, could point to a pre-Greek, Minoan deity.

Fertility bowl for the offering of fruits from Phaistos on display in the Archaeological Museum in Herakleion

See also

- Mycenaean religion to the religion of the Mycenaean rulers of Crete in the time of the last palaces and the post-palace period, which is mainly documented in Linear B script.

literature

- Jaquetta Hawkes: Birth of the Gods - At the Sources of Greek Culture . Hallwag AG Bern, Bern 1972, ISBN 3-444-10107-4 , p. 226 f.

- Polymnia Muhly: The Great Goddess and the Priest-King . In: Expedition Magazine . tape 32 , no. 3 . Penn Museum , 1990, ISSN 0014-4738 , p. 54–61 (English, online [accessed December 17, 2018]).

- Peter W. Haider: Minoan deities in an Egyptian medical text . In: Potnia: deities and religions in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 8th international Aegean conference Göteborg , Göteborg University, vol. 12, Gothenburg 2000.

- J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans. Konrad Theiss Verlag GmbH, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1862-5 , pp. 6, 50-52, 87-92, 152-156, 168 f., 171.

- Louise Schofield : Mycenae, History and Myth. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2009, ISBN 978-3-8053-3943-8 , pp. 144-169.

- Harald Haarmann : The riddle of the Danube civilization - The discovery of the oldest high culture in Europe. Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62210-6 , page 241.

- José Luis García Ramón : Mycenaean Omomastics . In: Yves Duhoux , Anna Morpurgo Davies : A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and their World . Volume 2. Peeters, Louvain-la-Neuve-Warpole 2011.

- Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, ISBN 978-0-252-07967-2 .

Web links

- Press Release for Mysteries of the Snake Goddess published by Kenneth DS Lapatin [1]

References and comments

- ↑ Emile Gilliéron and his son played a decisive role in the reconstruction of the Knossos finds. The authenticity of the Minoan snake goddess of Knossos (Minoan religion) is seriously questioned based on the results of the radiocarbon method ( 14 C dating).

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Snake Goddesses, Fake Goddesses. How forgers on Crete met the demand for Minoan antiquities. Archeology (A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America) Volume 54 Number 1, January / February 2001

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Mysteries Of The Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, And The Forging Of History Paperback. Da Capo Press, 2003, ISBN 0-30681-328-9

- ↑ a b J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 50 f.

- ↑ a b c d e J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 51 f.

- ^ J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 52.

- ↑ a b c d e J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 88 f.

- ^ J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 89.

- ^ J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, pp. 89-92.

- ↑ a b c d J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 152 f.

- ↑ a b c d e J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 153 f.

- ↑ a b J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 168 f.

- ^ J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 171.

- ↑ a b c J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 154 f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 155 f.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 7 f.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, pp. 155, 218 f.

- ^ A b c Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, pp. 218 f.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 219.

- ^ A b c Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, pp. 177 ff.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 179.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 161.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 166.

- ^ A b c Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 155 f.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 154.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 62.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 152.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 116.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 131.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, pp. 117 f.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, pp. 173 f.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 168.

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Snake Goddesses, Fake Goddesses. How forgers on Crete met the demand for Minoan antiquities. Archeology (A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America) Volume 54 Number 1, January / February 2001

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Mysteries Of The Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, And The Forging Of History Paperback. Da Capo Press, 2003, ISBN 0-30681-328-9

- ^ J. Lesley Fitton: The Minoans . Stuttgart 2004, p. 154 ff.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 152 ff.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 16 f.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 125.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 62.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, pp. 153 ff.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine. Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 171.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 116 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Peter W. Haider: Minoan deities in an Egyptian medical text . In: "Potnia: deities and religions in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 8th international Aegean conference Göteborg, Göteborg University", vol. 12, Göteborg 2000, p. 480 f.

- ↑ a b c d Peter W. Haider: Minoan deities in an Egyptian medical text . In: "Potnia: deities and religions in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 8th international Aegean conference Göteborg, Göteborg University", vol. 12, Göteborg 2000, p. 482.

- ^ A b Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 188.

- ↑ Harald Haarmann: The riddle of the Danube civilization . Munich 2011, p. 241.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 165.

- ↑ a b Jaquetta Hawkes: Birth of the Gods - At the sources of Greek culture . Bern 1972, p. 226.

- ^ A b José Luis García Ramón: Mycenaean Onomastics . In: Yves Duhoux, Anna Morpugo Davies: A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and their World. Volume 2 . Louvain-la-Neuve-Warpole 2011, p. 235.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Louise Schofield: Mycenae, history and myth . Mainz 2009, p. 160.

- ^ A b José Luis García Ramón: Mycenaean Onomastics . In: Yves Duhoux, Anna Morpugo Davies: A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and their World. Volume 2 . Louvain-la-Neuve-Warpole 2011, p. 230.

- ↑ a b c d e f José Luis García Ramón: Mycenaean Onomastics . In: Yves Duhoux, Anna Morpugo Davies: A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and their World. Volume 2 . Louvain-la-Neuve-Warpole 2011, p. 236.

- ↑ José Luis García Ramón: Mycenaean Onomastics . In: Yves Duhoux, Anna Morpugo Davies: A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and their World. Volume 2 . Louvain-la-Neuve-Warpole 2011, p. 234.

- ^ Louise Schofield: Mycenae, History and Myth . Mainz 2009, p. 161.

- ↑ a b c d José Luis García Ramón: Mycenaean Onomastics . In: Yves Duhoux, Anna Morpugo Davies: A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and their World. Volume 2 . Louvain-la-Neuve-Warpole 2011, p. 232.

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess - a Near Eastern Koine . Urbana, Chicago, Springfield 2013, p. 165.

- ^ A b Peter W. Haider: Minoan deities in an Egyptian medical text . In: "Potnia: deities and religions in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 8th international Aegean conference Göteborg, Göteborg University", vol. 12, Göteborg 2000, p. 479.