Nicolas Ferry

Nicolas Ferry (born October 14, 1741 in Champenay ; † June 8, 1764 in Lunéville Castle ) was the court dwarf of the Polish King Stanislaus I. Leszczyński .

Life

Nicolas Ferry was the first child of the farmer Jean Ferry and his wife Anne Baron. According to some sources, he was seven months old, according to others, when his mother was caught in labor and gave birth to her son before a midwife or other help could be called. Nicolas Ferry was born with a birth weight of 625 grams and a body length of 21 centimeters. His survival was initially seen as impossible, but his mother tried very hard for the tiny son: instead of a cradle, she upholstered a large wooden shoe in which she put the child, and since his mouth was too small to breastfeed him, became he reared with a small bottle. One month after his birth, he was baptized in the town church of Plaine . He spoke his first words when he was 18 months old; at the age of two he could walk.

The tiny child - his first shoes were four centimeters long - naturally caused a stir. In 1746 some ladies from the court of the Polish king Stanislaus I. Leszczyński, who also ruled over the duchies of Lorraine and Bar , visited the Ferry family. They were fascinated by the tiny Nicolas and told the king about the child, whereupon Stanislaus had one of his doctors, Monsieur Kast, examine the boy in July of the same year. At this point, Nicolas Ferry was about two feet tall and weighed a little over two pounds. Kast found that the boy was well proportioned. He had dark brown eyes, light blond hair, a shrill voice and a large, curved nose. Kast assumed that Nicolas Ferry would no longer grow - in fact, however, he later reached a height of 89 centimeters.

Stanislaus was so impressed by Kasts' report that he ordered Jean Ferry to take the child to his castle in Lunéville immediately. Nicolas' father obeyed this order and delivered his son to the king, who suggested that Nicolas be kept and brought up at court. Fifteen days later, Nicolas' mother visited him again to say goodbye. The little boy didn't seem to recognize her at first, but wept bitterly when she disappeared. Stanislaus, who now considered the boy to be his personal property, gave him to Queen Katharina Opalińska for her birthday in 1747 . She gave him the name "Bébé", which was to accompany him from now on, and gave him away in the same year, lying on his death bed, to her cousin, the Princess de Talmont. The new owner pressed for the promised good education to be given to the child. In the years that followed, numerous educators tried to teach Nicolas Ferry something, but with little success. The boy finally spoke French with some skill and could dance, but was unable to read or write a single letter or play an instrument, although he loved music and liked to beat the beat on a snare drum.

The king also had him tailor numerous items of clothing and build a small house with several rooms and a wagon that was pulled by four goats. Nicolas Ferry would withdraw into the house, which stood in a hall of the castle, sulking whenever he felt offended - which amused the king to the greatest extent. Ferry had a fool's freedom at court, and his pranks were feared. Even when he threw a lap dog of the Princess de Talmont out of the window out of jealousy, he was not punished.

In 1759, however, Ferry's unbroken rule in Lunéville Castle ended: Princess Humiecka brought the Pole Józef Boruwłaski to Stanislaus' court. Not only was Boruwłaski shorter than Ferry, he was also intelligent and funny. He was nicknamed "Joujou" and quickly overtook Ferry. Eventually the situation escalated: Nicolas Ferry tried to drag his competitor into a fireplace. However, Boruwłaski's cries for help summoned the king before Ferry could kill the rival, and for the first time in his life he was beaten. This came as such a shock to him that he lost speech for several days. Incidentally, Boruwłaski did not care to take Ferry's place at Stanislaus' court. He soon left Lunéville Castle and moved on to Paris , and Ferry returned to the position he had believed to be lost.

The interlude with Boruwłaski prompted various doctors and scientists to compare the two court dwarfs with each other or to examine Ferry more closely. The doctor Saveur Morand made him the subject of a lecture at the Academy of Sciences, and the nobleman Louis-Élisabeth de la Vergne de Tressan wrote a pamphlet in which he compared the mental state of Ferrys to Boruwłaskis. The result was devastating for Ferry and was read to him roughly and bluntly. This led to such an outbreak of desperation that the Princess de Talmont wrote a kind of counter-statement to protect and defend her Bébé.

Sickness and death

At the age of 16, Nicolas Ferry began to go through a terrifying change. Gradually he hunched over, was unsteady on his feet, and lost his teeth. His face was so emaciated that his large nose resembled a bird's beak. Denis Diderot , who saw Ferry when he was 19 years old, was appalled by this aging process. The court doctor Kasten Rönnow and other medical professionals were entrusted with the case. They blamed Ferry's decline on the influences of puberty and his sexual excesses. Twice attempts had been made to marry Ferry. The first time, a young woman of normal stature had been chosen for him, whose parents, however, opposed the marriage. The second time, Thérèse Souvray , who was also short, was to be the wife of Ferry, who at first was not averse to taking the wealthy court dwarf as a husband, but refrained from doing so after the first personal encounter. Although Ferry's illness was seen by some as a reaction to this rejection, by the year of the planned marriage, 1761, the symptoms were already evident. In 1762 his condition deteriorated so much that he became bedridden and incontinent . The doctors still had no advice. Ferry experienced another phase of improvement, but after he fell ill with a cold in May 1764, his strength could no longer withstand. He confessed to a court chaplain on June 5, received the last unction and died on the morning of June 8, 1764.

After death

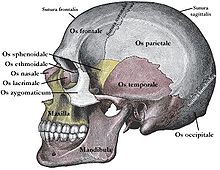

King Stanislaus mourned his dead court dwarf bitterly and was initially not ready for an autopsy , but was finally persuaded to release Ferry's body for the service of science. In return he was promised to prepare and assemble Ferry's skeleton. Kasten Rönnow carried out the autopsy together with the French doctors Perret and Saucerotte and the Comte de Tressan, who had once judged Ferry's mental state so little benevolently, watched. The doctors found that Ferry's internal organs and genitals were not damaged, but his skeleton was marked by scoliosis . Going beyond the official autopsy report, Saucerotte reported in 1768 that a spongy tumor was found between the two parts of the parietal bone , which must have pressed directly on Ferry's brain.

After the autopsy, Rönnow cooked Ferry's skeleton according to his promise, but did not assemble it, but gave it to the king in a box that was kept in the library of the castle. The rest of the body was buried in the Église des Minimes in Lunéville . The mausoleum with the decorated urn bore a Latin inscription in which the date of Ferry's death was June 9th.

Stanislaus apparently never got around to calling for the assembly of the skeleton: two years after the death of his court dwarf, the king's clothes caught fire as he warmed himself in front of the fireplace in his bedroom. Since the door guard had been strictly instructed not to let anyone into the room, he fended off all persons who rushed to Stanislaus' cries for help by force of arms. When he was finally overwhelmed, any help came too late for the king.

After Stanislaus' death, Ferry's skeleton ended up in the Cabinet du Roi in Paris. There it was examined by Georges-Louis Buffon . In addition to the well-known scoliosis and toothlessness, he also diagnosed genoa valga and osteoarthritis . He also found that the skeleton was no longer complete: two ribs and several hand bones were missing from Ferry. When assembling the skeleton, Buffon had to use the cabinet and children's bones.

Diagnoses

Ferry's short stature as well as his early aging process and death occupied the medical profession again and again. Dr. Virey put forward the theory in the 19th century that he had suffered from rickets and also from a fetal disease, which the doctor did not narrow down. Other doctors believed that his mother's placenta was unable to properly feed the future child. After Nicolas, Madame Ferry gave birth to other children who were healthy and normally developed. In 1890 the theory emerged that Nicolas Ferry was a victim of congenital syphilis . The findings at the autopsy and the good health of all other members of the Ferry family speak against this. In 1897, L. Manouvrier went back to the damage to Ferry's parietal bones, which Saucerotte had already mentioned, but did not come to a conclusive conclusion. In 1911 Sir Hastings Gilford contradicted the old diagnoses and suggested that it might have been a case of ateleiosis . Helmut Paul George Seckel later built on this theory and described the clinical picture in detail, including in the case of Ferry. Today it is called Seckel syndrome after the author . According to Jan Bondeson , however, Ferry's early and rapid aging process is not necessarily typical of Seckel syndrome. Bondeson believes Ferry suffered from a variant of progeria .

Footsteps of Ferry

The Église des Minimes was destroyed during the French Revolution , but the mausoleum containing Ferry's remains was saved. It is now in the Musée du Château du Lunéville . The skeleton later came to the Musée d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris and is now kept in the Musée de l'Homme . Ferry's clothes ended up in the Musée d'Unterlinden , the Musée de Lunéville and the Benedictine Abbey of Senones , his drinking set in the Musée d'Amiens and his goat cart in the holdings of a private collector. This cart was later used as a toy in a patrician family in Lunéville, and when it was no longer decorative enough, it was sold to a poor man who used it to transport vegetables. Then his track was lost.

There are replicas of Nicolas Ferry and oil paintings showing him in many European collections. A porcelain figurine, created soon after Ferry moved to Stanislaus' court and showing him in a hussar uniform, was destroyed in a fire in 2003. A waxy replica was made by a Monsieur Jeanet from Lunéville when Ferry was 19 years old for the lectures at the Academy of Sciences and is now in the Musée Orfila in Paris, another was by François Guillot, who worked in Nancy , and became another probably made after Ferry's death in the Cabinet du Roi. Today replicas of Ferrys can also be seen in Drottningholm Palace in Sweden , in the Hessian State Museum in Kassel , in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig , in the Musée Historique Lorraine in Nancy and in the Musée Municipal in Castle Lunéville.

The band Ange recorded a song called "Le nain de Stanislaus" which was released on the album "Émile Jacotey".

literature

- Jan Bondeson: The Two-Headed Boy and Other Medical Marvels. Cornell University Press, Ithaca and New York, ISBN 0-8014-8958-X , pp. 189-216

Web links

- Medical findings and numerous images (PDF file; 844 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.thefrenchporcelainsociety.com/ArtworkImages/CatalogueFiles/newsletterspring2004.pdf ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ferry, Nicolas |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bébé |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Court dwarf |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 14, 1741 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Champenay |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 8, 1764 |

| Place of death | Lunéville Castle |