Nike des Paionios

The Nike des Paionios is one of the few antique round plastic Nikes that has been preserved as an artist's original . The Greek sculptor Paionios von Mende created the classical sculpture around 420 BC. From Parian marble. The Nike was donated to the god Zeus in Olympia by the Messenians and Naupakti, allied with Athens in the Attic League . The occasion of the dedication was a victory in an unspecified war, which is probably the Peloponnesian War . In the 5th century BC In BC Nike becomes a synonym for a military victory and can be associated with historical events for the first time.

The original of the sculpture can be seen today in the Archaeological Museum in Olympia (inventory number 46-8).

Find history

The fragmentary remains of the sculpture and the base were found in Olympia during the German excavation campaigns from October 1875 to May 1876 and the years 1880 and 1881, under the direction of Ernst Curtius , Gustav Hirschfeld and Friedrich Adler , and were able to be found by agreement in material and Processing tracks can be assigned to a single figure. In March 1876 and Adler Curtius discovered the in situ underlying foundation of the triangular base, the individual blocks and the plinth are also obtained. The inlet tracks of the plinth allow an assignment to the sculpture of Nike des Paionios and localize the original location of Nike about 30 meters southeast of the Temple of Zeus in Olympia , where it was set up as a booty anathem .

The head of the statue was found more than 100 meters from the base on November 3, 1879. It could be assigned to the statue on the basis of stylistic and metric studies.

description

The figure is only preserved in fragments. The upper and lower body of the Nike have been largely preserved and show a female figure with wings on the shoulders. The Nike is shown floating and clad with a himation that bulges behind her. She also wears a thin undergarment, which is held by a fibula on the right shoulder. The robe has loosened from the left shoulder and reveals the chest. The peplos is held at the waist by a belt. The finely divided folds of the peplos stand out from the broad, regular folds of the himation , which is marked in this way as a significantly heavier material. The figure's left forearm moves almost horizontally away from the body. In addition, the folds of the himation show that the missing left forearm must have been angled upwards and that she was holding the himation up with her left hand. The right upper arm and the corresponding hand fragment, however, were aligned parallel to the body. In addition to the wings and face, the neck, both forearms, the left hand and most of the himation are missing . The figure has a height of 1.95 meters (with head 2.21 meters).

The Nike des Paionios, with its unserved, originally spread wings, is depicted floating down from the sky. She seems to have already put her left foot forward to land. However, it does not touch the ground as there is an eagle under its feet. This separates the sculpture from the plinth. The seemingly sloping hip line is only due to the belt and the apoptygma that is waving to the right . The torso of the figure does not follow the rules of ponderation . This means that the lower body of the Nike is constructed like that of a standing sculpture. However, various elements make it clear to the viewer that it is by no means standing. The left leg is forward, while the right one appears to be set back and shortened. In fact, the sculpture can conditionally be described as pondered if its right is understood as a free leg and the left as a supporting leg. In addition, the three-sided shape of the pillar meant that it was no longer perceived as a geometric body, but as a surface, due to the rigid one-sidedness of the figure. Accordingly, it did not act as a stand for Nike. The shape of the pillar, the positioning of the Nike and the front view of the figure are artistic design elements that support the depiction of floating.

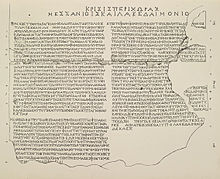

Inscriptions

On some blocks of the base the inscriptions belonging to the monument have been preserved.

The dedication inscription

inscription translation » Μεσσάνιοι καὶ Ναυπάκτιοι ἀνέθεν Διὶ / Ολυμπίωι δεκάταν ἀπὸ τῶν πολεμίων « The Messenians and Naupaktier dedicated this to the Olympian Zeus from the tithe of the spoils of war.

The two-line dedication inscription is preserved on block E of the pillar. It emerges from it that the Messenians and the Naupaktier dedicated this monument to the Olympian Zeus from the tithe of their spoils of war. However, the assignment to a certain consecration and thus to a certain battle is made more difficult by the fact that the defeated enemies are not named in the inscription. Further information is given in the writings of Pausanias and Thucydides . Both ancient authors deal with the occasion of dedication. Pausanias indicates that the Messenians claimed to have the Nike mark its victory in 425 at Sphacteria , a small island off Pylos , consecrated and the name of the vanquished fear of the Lacedaemonians not named, "because before the Acarnanians and Oiniaden fear but nobody ” . Pausanias himself, however, contradicts this interpretation and rather believes that a battle against the Acarnans and Oiniads around 455 BC. Was the actual occasion of this consecration. Friedrich Koepp writes about this, "the Messenians pass off as their enemies those who were least disgraceful to fear, but who were most glorious to defeat" . The consecration given by Pausanias cannot, however, correspond to the circumstances, since the Akarnans fought on the side of the Athenians in this battle and were therefore not enemies but allies of the Messenians. In addition, due to stylistic features, it is unthinkable to mark the monument with a battle of 455 BC. And then with a dating of the sculpture to the middle of the 5th century BC. To bring in connection.

In addition, the assertion of the Messenians, reproduced by Pausanias, that the battle of Sphakteria was the occasion of the consecration , cannot be accepted without further ado. In his report on this battle, Thucydides mentions the Messenians only in general and their auxiliaries, but not explicitly the Naupaktiers. In addition, so much booty could hardly have been made at Sphakteria that a tenth would have been enough for such a monument.

Koepp was able to establish, however, that the failure to mention the enemies in the inscription is by no means an isolated case. She was not the only anathema in Olympia who did not mention the names of the defeated enemies. He questions that the Messenians did not mention the enemy for fear of the Spartans . It is quite possible that the Battle of Sphakteria could be seen as an occasion for dedication. The failure to mention the enemies can be explained by the fact that not one, but several successful battles in the Archidamian War were the motif of this dedication.

The actual occasion of the consecration cannot therefore be conclusively clarified on the basis of the dedication inscription. However, the focus here is clearly on political and non-sporting motives.

The artist's inscription

inscription translation » Παιώνιος ἐποίησε Μενδαῖος καὶ τἀκρωτήρια ποιῶν ἐπὶ τὸν ναὸν ἐνίκα « "Paionios von Mende made me and he won [in the competition for the contract] for the akrotere of the temple".

Immediately below the dedication inscription on block E of the pillar, the artist's inscription, which is also two-line, has been preserved. It clearly shows that Paionios von Mende was the creator of the sculpture, but was also responsible for the acrotere of the adjacent Temple of Zeus. The acroters mentioned are not archaeologically known. In the inscription, Paionios explicitly states that he is not only the sculptor of Nike, but also that he has also won an artist competition. This competition was held to award the contract for the manufacture of the acroters of the Temple of Zeus. What is striking is the artistic self-confidence that prompted Paionios to use this victory statue to document his personal success.

The crisis inscription

The youngest of the surviving inscriptions is the so-called crisis inscription . It contains an arbitration ruling by the Milesians on the membership of the Dentheliatis , the border area between Messene and Sparta. The Roman consul Quintus Calpurnius Piso mentioned in the inscription allows the arbitration to be dated back to 135 BC. To date. Also Tacitus tells of a protracted dispute, their property rights in which both parties over the past the border sanctuary of Artemis Limnatis claims made. In 146 BC In BC Lucius Mummius finally rearranged the territorial relations in Greece and assigned it to the Milesians to judge. He again set up a court of arbitration to determine the affiliation of the disputed area. The Milesians decided in favor of the Messenians and awarded Messene this economically insignificant piece of land. The affixing of the crisis inscription, which refers to a victory over Sparta, on the pillar of the Paionios-Nike makes it clear that even 300 years after the installation of the anathem, its anti-spartan significance was not lost in the consciousness of the Athenians.

reconstruction

The base

Curtius and Adler found sufficient remains of the pillar to be able to reconstruct it in detail. It consisted of a total of 12 blocks that tapered towards the top. The lowest block A has a side dimension of approx. 1.90 meters. The top block N, however, is only about 1.19 meters. The traces of entry on the plinth show that the sculpture originally on it was oriented towards the east-facing long side of the three-sided pillar. The total height of the pillar will be reconstructed to a height of 8.5 meters.

The sculpture

Due to the substance obtained, an almost complete reconstruction of the figure is possible. The first attempt at this was presented by Richard Grüttner in 1883 and shows the Nike with a palm frond in her right hand, while the hem of her coat, which curves in the wind, rests freely in the air behind her.

Another reconstruction was made by Rühm on the basis of Grüttner's earlier work in 1894. He makes slight changes, the most noticeable again relating to the right hand. The Nike shows fame without adding an attribute. She holds on to her coat not only with her left but also with her right. In this way, the illusion of floating and the jacket puffing up in the wind is shown realistically. In this reconstruction, not only the folds of the mantle, insofar as it could be reconstructed, are taken into account, but also the other fragments belonging to the sculpture that came to light during the excavations.

A third reconstruction was again made by Grüttner in 1918 and represents a revised version of his first work. This allows Nike to grasp the end of the coat with her right hand. However, he postulates a victory armband as a further attribute that he also gives Nike to the hand.

A reconstruction and the interpretation of the content of the motif are made more difficult by the fact that Nike is mostly depicted in different functions on vase pictures . These do not reveal a clear scope of duties for Nike. With the end of the archaic era, the almost stereotypical representation of Nike in the knee-run scheme changes , so that in addition to other emerging movement motifs , the area of action of Nike also grows.

In the red-figure vase painting , she appears as a donor to the victim, as a companion in agonal competitions, as an attribute of a victorious deity or, as on a bronze sheet from the early 5th century BC. Depicted as a charioteer of a four-horse carriage. The representation in connection with a military victory is only a minor aspect of the vase painting. In the round sculpture, however, this point is the only aspect that is considered. This results from the listing of the Nikes as anathemes. Here she appears as a single figure without attributes. It is obvious that while Nike is understood almost exclusively on the basis of its attributes and the accompanying scenes in other genres of art, this does not seem necessary in the case of round sculpture. It is used solely as a symbol for a military victory that has been achieved.

A Roman replica of a head from the Hertz Collection in Rome, based on a Greek model from the last quarter of the 5th century BC, can be used to reconstruct the face. Goes back. This so-called Hertzian head is almost identical to the surviving fragment of the head of Nike des Paionios. In accordance with the Hertzian head, the main hair laid in fine waves over the head with the hair band and the hair pulled together at the nape of the neck with curls behind the ears can be reconstructed for the Nike.

Deployment context

After their victory over the Athenians and their allies at the Battle of Tanagra in 457 BC. The Spartans donated a golden shield to Olympia, which they had attached to the ridge of the Temple of Zeus together with an inscription stone. The inscription, which is not completely preserved, could, however, be completed with the help of the Pausaniastext. This anathema could be clearly perceived by any ancient observer as the pictorial defeat of Athens because it was attached to the most important temple of the sanctuary. In addition, it was attached to the highest point of the temple, which increases the importance of this Spartan victory and the emphasis on Zeus as the official bearer of this victory. Even without the inscription, the ancient observer might have known the intention and the ideological concept of this anathem.

The emphasis on this Spartan victory was intended to demonstrate the military superiority of the Spartan state over the Athenians in the Peloponnesian War . Against this background, the listing of Nike des Paionios, which has a clear anti-spartan intention, is of particular importance.

It must be seen as a pictorial and political response to the anathema of the Spartans, which not only diminishes the Spartan victory at Tanagra through the constellation, but also depicts the struggle for supremacy between Athens and Sparta. In this way the conflict between Athens and Sparta is also carried out in the sanctuary of Olympia.

The Nike des Paionios is directly related to the so-called Tanagra shield and specifically refers to the anathema. The installation of the Nike with its back to the Temple of Zeus presented an impressive picture to the ancient observer from the east. The Nike des Paionios made the Temple of Zeus and the attached antiathenic anathema into its backdrop through this type of installation. In this way it expressed the superiority of Athens and symbolically erased the success of the Spartans.

Another monument that joins this anathematic dialogue are the so-called Niken des Lysander . They are not archaeologically transmitted, but only known from a mention by Pausanias and can be brought into a close contextual context with the Nike des Paionios through their motif alone. The fact that the motif is taken from Olympia and that the Niken des Lysander are to be dated after the Nike of the Messenians can be seen from the accompanying inscription and the commentary by Pausanias. The Niken des Lysander were erected after the battle of Aigospotamoi in the sanctuary of Athena Ergane in Sparta and are based on the Nike des Paionios in their elaboration.

The adoption of this motif to Sparta, which in Olympia is clearly afflicted with an anti-Spartan intention, did not happen unconsciously and has a purely historical background. In this context, the motif is of particular importance. Because it evidently becomes a symbol for the dispute and the anathematic dialogue between Athens and Sparta. The Niken des Lysander take up the motif and do not even adapt it to the external framework. The significance of a Nike standing on an eagle can be seen in a Zeus sanctuary like Olympia and illustrates - despite the increasing political moment of the anathema - the connection to Zeus. To set up this motif unchanged in an Athena shrine raises the question of the intention and importance that this motif was assigned to the Spartans.

The Niken des Lysander must surely be seen as a political answer to the Nike des Paionios. The adoption of the motif looks inappropriate at first glance. Not only is Zeus' companion animal depicted in a sanctuary of Athena, but a motif is also adopted, which in Olympia has a clearly anti-Spartan intention to demonstrate a Spartan victory over Athens. One expressly turns away from the intention of such an anathema as a pure gift of thanks to the deity. Although the Niken des Lysander were officially consecrated to Athena, the contextual reference to her is completely absent. Rather, especially in this case, the historical aspect of the anathema comes to the fore. The provocative concept of the anathema also becomes clear from the consecration of Niken des Lysander. The battle of Aigospotamoi brought the decision about the outcome of the Peloponnesian War and culminated in the surrender of Athens.

The Spartans decided in a polemical way to depict the pictorial representation of this extremely high-ranking victory with the same motif, which in Olympia was clearly linked to an antispartan basic idea. They also had it set up in duplicate. This conscious parallelism represents an enormous humiliation of the Athenian state and a clear degradation of already won Athenian victories over Sparta.

literature

- Wilhelm Dittenberger , Karl Purgold et al .: Olympia: the results of the excavation organized by the German Reich. Text volume 5: The inscriptions from Olympia , Berlin 1896

- Alexandra Gulaki: Classical and Classicist Nikedabbilder . Dissertation Bonn 1981

- Klaus Herrmann : The pillar of the Paionios-Nike in Olympia , in the yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute 87, 1972, pp. 232-257

- Tonio Hölscher : The Nike of the Messenians and Naupaktier in Olympia , in the yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute 89, 1974, pp. 70–111 ( digitized version )

- Friedrich Koepp : About the dedicatory inscriptions of Nike des Paionios , in Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 50, 1895, pp. 268–276

- Hans Pomtow : The three-sided basis of the Messenians and Naupaktier zu Delphi , in New Yearbooks for Philology and Pedagogy 153, 1896, pp. 505-536

- Hans Pomtow: The Paionios-Nike in Delphi , in the yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute 37, 1922, pp. 55–112

- Bernhard Schmaltz : Type and Style in the Historical Environment , in the yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute 112, 1997, pp. 77-107

- Michael Siebler : Olympia. Place of games. Place of the Gods , Stuttgart 2004, pp. 112–115

Web links

- Virtual collection of the University of Göttingen

- Nike des Paionios in the Basel Sculpture Hall

- Nike des Paionios in the Arachne archaeological database

Individual evidence

- ↑ DNP VIII (2000) 1171 sv Olympia (E. Olshausen).

- ↑ Siebler 2004, p. 112.

- ↑ from Dittenberger – Purgold 1896, p. 379.

- ↑ Dittenberger – Purgold 1896, pp. 377–384; Inscriptiones Graecae IX, 12 3: 656 .

- ↑ pause. 5, 26, 1.

- ↑ Koepp 1895, p. 269.

- ↑ Thucydides 4:32 .

- ↑ See Dittenberger – Purgold 1896, p. 381.

- ↑ Koepp 1895, p. 271.

- ↑ Siebler 2004, pp. 154f.

- ↑ Dittenberger – Purgold 1896, p. 380; Inscriptiones Graecae IX, 12 3: 656 .

- ↑ from Dittenberger – Purgold 1896, pp. 105-106.

- ↑ Dittenberger – Purgold 1896, pp. 103–110.

- ^ Tacitus, Annales 4:43 .

- ↑ Pomtow 1922, p. 59.

- ↑ Pomtow 1922, p. 62.

- ↑ pause. 3, 17, 4.