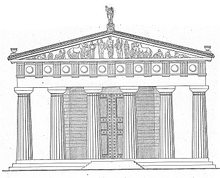

Temple of Zeus (Olympia)

The Temple of Zeus at Olympia was the dominant building in the Olympic sanctuary and was built in the years from about 480/470 to 456 BC. Built in BC. The temple, which is around 64 meters long, 28 meters wide and 20 meters high, is one of the most important buildings of early classical architecture . It was the largest temple in the Peloponnese and at the time of its construction the largest temple in the Greek motherland . On the fifth day of the Olympic Games , all athletes and spectators went there in a solemn procession to sacrifice cattle on the fire altar of Zeus north of the temple at the religious climax of the Games, which were then eaten in a common feast.

history

Between about 480/470 and 456 BC The otherwise unknown Libon, allegedly from the area, directed the construction work on the Temple of Zeus. In general, one follows the statement of Pausanias that the temple and the image of Zeus ( ἐποιήθη δὲ ὁ ναὸς καὶ τὸ ἄγαλμα τῷ Διὶ ) were the spoils of a victory which the Eleans around the year 472 BC. BC had won over Pisa , was built. The authorship of the Eleans, however, must remain doubtful in view of the immense costs that can be estimated with several hundred talents for the temple and statue of Zeus. Despite intensive archaeological research in Elis, the necessary wealth of the city cannot be recognized, which also applies to the defeated Pisatis. In addition, Pisa was already a hundred years earlier, i.e. 572 BC. During the reign of Pyrrhus of Elis, smashed and incorporated. From a re-establishment of Pisa before that of the 4th century BC BC, which led to the battle on the Altis, is not known. It is implicitly or explicitly assumed that the Eleans could at best finance the temple, but not the Zeus portrait created almost two decades later.

In 456 BC The temple must have been completed to such an extent that the Spartans could have a golden shield with a foundation inscription attached to the frieze of the temple front. According to Pausanias it read:

"Ναὸς μὲν φιάλαν χρυσέαν ἔχει, .DELTA..di-elect cons Τανάγρας ἐκ

τοὶ Λακεδαιμόνιοι συμμαχία .tau ἀνέθεν

δῶρον ἀπ Ἀργείων καὶ Ἀθαναίων καὶ Ἰώνων,

τὰν δεκάταν νίκας εἵνεκα τῶ πολέμω."

"The temple has a golden shield, from Tanagra

the Lacedaemonians and their allies consecrated

a gift from the Argives and Athenians and Ionians a

tithe for victory in the war."

The Battle of Tanagra , in which the Spartans defeated the Athenians and their allies in the first Peloponnesian War , took place in 457 BC. Instead of. This date is the only certain point in time that can be connected with the erection of the temple.

After 438 BC The sculptor Phidias began to make the colossal image of Zeus of the temple out of gold and ivory . In this context, the interior of the temple was radically redesigned, for which even the pillars were dismantled and rebuilt with a different center distance. The temple must have existed as early as the 4th century BC. Underwent considerable repairs, probably as a result of the earthquake of 374 BC. Components of the Temple of Zeus were found in the foundations of the Echo Hall and in a later abandoned hall foundation. Parts of the beams of the east facade were installed in the west facade in a later repair. In some cases, entire parts of the building must have been dismantled and rebuilt, especially the eastern vestibule in front of the cella. Repairs and renovations also affected the gable figures. At least 37 column drums in the temple itself were reworked into pieces of entablature and reinstalled on the temple, the same applies to 17 pieces of entablature, which were reused as pillar drums on the temple after reworking. Major maintenance work also took place in the time of Agrippa , but especially under Diocletian .

The temple stood upright until the 6th century AD. Theodosius I ordered the closure of all pagan cult sites in 391 AD, but cult activities in Olympia were maintained until the beginning of the 5th century AD. It was not until Theodosius II finally banned the Olympic Games in 426. Two earthquakes in 522 and 551 finally destroyed the temple, throwing the pillars into the positions in which they can still be seen today. In the period up to its excavation, the ruins were partially built over by residents of the area with simple houses and buildings, and stone robbery also hit the ruins. Over the centuries, a large part of the temple disappeared under the deposits of Alpheios and the masses of earth of the Kronos Hill, which repeatedly covered the Altis, the sacred grove of Olympia, as a result of earthquakes.

The first smaller excavations of the temple began in 1806, and large parts of it were uncovered in 1829 by the French Expédition scientifique de Morée . Systematic investigations of the Temple of Zeus did not begin until the German excavations in Olympia began in 1875, which initially lasted until 1881. Between 1906 and 1909 Wilhelm Dörpfeld tried to clarify problems of dating through further excavations, which he did not succeed, so that he undertook new efforts in the years 1921–1923 and 1927/28. However, it was not until the beginning of the 1940s, but above all from 1952 to 1966, that individual observations and investigations into proportions and design or individual structural elements such as the lion's water spouts were able to gain new insights into the architecture and position of the Temple of Zeus.

The current research of the German Archaeological Institute is devoted to various questions on the measurement system and metrology, on problems of cell design, on measures of optical refinement as well as on the scope and dating of verifiable repair activities based on recently carried out, exact measurements. Overall, the aim is to publish the Temple of Zeus in a manner appropriate to the present day.

architecture

A sufficient number of structural elements have been preserved from the temple in order to be able to largely reconstruct its former appearance. The building material used was predominantly a porous shell limestone in the vicinity of Olympia, which, despite its coarse surface structure, was cut and processed extremely precisely. All visible surfaces were covered with a thin stucco, only about 1 mm thick, and individual structural elements were colored. Special structural elements such as the roof and roof edges, gable figures and relief components were executed in marble.

Substructure

The building rose on a 3 meter high foundation, which was filled with earth all around up to the upper edge of the Euthynterie as the uppermost and already semi-visible layer of the concealed foundation . This was followed by a three-tier substructure, the Krepis , the lower step heights of which were 48 centimeters, while the top step, which also formed the stylobate , i.e. the base of the columns , was raised by 8 centimeters and thus particularly emphasized. The Krepis had a total height of 1.52 meters. The temple thus rose optically on an artificially created hill, which raised it above the rest of the Altis terrain and underlined its importance. A ramp in the middle of the eastern temple front made access easier.

Layout

At the level of the stylobate, the long rectangular temple had a size of 27.68 × 64.12 meters and was thus the largest detectable temple in the Peloponnese . The temple had a peristasis called ring hall of 6 x 13 columns, was thus a hexastyler Peripteros . The pillars of the front were formed here with a lower diameter of 2.256 meters slightly stronger than the pillars of the long sides of 2.231 meters. The center distance of the pillars, the yoke , was 5.22 meters, but was reduced by 43 centimeters at the corner pillars to compensate for the Doric corner conflict by means of this contraction .

In contrast to older temples, the 46.84 × 16.39 meter large Naos was integrated into the yoke system of the column position. The outer sides of the naos walls lay in the column axes of the second and fifth front columns. The naos had a vestibule, the pronaos , and a rear hall, the opisthodom , each of which was framed by ante and separated from the peristasis by two antis columns . The foreheads of the antennas were centered in the second and eleventh yokes of the long sides. This resulted in the width of the ptera , i.e. the circumferences of the peristasis, of 3.24 meters on the long sides, but 6.22 meters on the narrow sides. The floor was originally covered with square poros tiles, which were later covered with a mortar screed. In Roman times, the floor was covered with hexagonal agates, remains of which have been preserved in the eastern Pteron.

The 13.06 × 28.74 meter interior of the cella was divided into three aisles by two-story column positions, with the approximately 6.65 meter wide central nave being twice as wide as the side aisles. The column positions inside the cella did not correspond to those in the ring hall, so they were subject to their own rhythm and system of proportions, which was detached from the exterior. The entire width of the back third of the central nave was taken up by the 6.65 × 9.93 meter base, which carried the colossal seat of Zeus. In the middle third there was a large basin made of dark gray to black-bluish slabs of Eleusinian limestone, which were framed by white marble.

Elevation

Ring hall

The rising architecture of the temple was of the Doric order . Between the at least - none of the columns is intact with all of the drums, even on the south column 5 from the west the lowest drum is damaged - the 10.50 meter high columns, the distance between the columns, the intercolumnium , was about 3 meters. The pillars consisted of 20 flutes , which met with a sharp ridge, but were less deeply fluted on the pillars at the front than on the other pillars. They tapered on the fronts to 1.78 meters, on the long sides to 1.685 meters. The significantly stronger weighting of the front pillars as a result seems to be reminiscent of older, archaic systems of proportions with their increasingly clear emphasis on the front . On the other hand, the more compact shape of the columns, which have only a slight curvature called entasis and whose ratio of lower column diameter to column height was 1: 4.7, is progressive .

Different style levels can be seen on the capitals , suggesting a sequence of work from the front over the back to the long sides. While the upholstery of the capitals, the echinus , begins on the east side in a moderately concave profile, and then merges with a slightly convex curve into the curve of the capital shoulder, the echinus of the long-side capitals rises at a 45 ° angle almost in a straight line to the cover plate of the capital, the abacus , and breaks into the steeply profiled shoulder in a short curve. While on the east side the work pieces of the capitals start in the uppermost groove of the anuli , on the long sides a larger piece of the column neck is attached to the capital.

On the pillars rested the more than 5 meters, at the corners 5.76 meters long and 1.77 meters high architrave blocks . Since the overall thickness of the architrave was over 1.96 meters, its blocks were made in three equally deep, staggered panels one behind the other. The architrave ended at its upper edge in a band under which there were drip strips, the regulae . Above it was the 1.74 meter high Doric frieze with its 1.06 meter wide triglyphs and mostly specially made, unadorned metopes averaging 1.55 meters wide. Two metopes each came to stand over an intercolumn, with the triglyphs slightly shifted outwards from the column axes. This was probably made necessary by the extension of the triglyphone due to the inclination of the south-eastern corner column that came about over time. Traces of this repair can be found under the workpieces. Lucius Mummius had 146 BC AD 20 gold shields on the metopes around the temple, a foundation from his booty after the destruction of Corinth .

A 64.5 centimeter high and 84 centimeter overhanging geison , whose teardrop plates, mutuli, corresponding to the triglyphone, each had 3 × 6 drops , closed off the entablature. The Sima that followed above had a gargoyle in the shape of a lion's head above each mutulus plate and, like the entire Corinthian roof, was originally made of Parian marble , later replaced by workpieces made of Pentelic marble .

The gable fields, which were used to accommodate groups of figures, had a depth of 1.01 meters on the east side, but only 0.90 meters on the west side. The base of the gable fields called the tympanum had a clear width of about 26.50 meters, the middle of the gable was about 3.34 meters high in the clear. 40 centimeter high oblique geisa with the following Doric kymation as a water nose closed the gables at the top. A plinth on the horizontal geison of the fronts served to erect the gable figures. Corresponding mortise holes on the east side testify to the associated work and efforts. The gable-sided horizontal geisa had no further closure in the form of a kymation.

The temple, which is about 20 meters high from Krepis to First, was crowned by akroteren , in the form of gold tripods on the gable corners, in the form of gold niches , which is precisely what the Pausanias says of 68 feet (= 20.13 meters) on the ends of the ridge. The niken were inscribed by the sculptor Paionios in the late 5th century BC. Manufactured. Fragments of the acrotary box that carried the Nike on the west side have been preserved. Palmettes made of Parian marble, probably corresponding with the gargoyles, closed off the ridge. Repair pieces of other material were also found from these components.

Naos

The 16.39 meter wide pronaos with its 10.44 meter high ante and its two equally high Doric columns, like its counterpart, carried a 1.69 meter high architrave on the back, followed by a 1.75 meter high Doric frieze. The frieze thus slightly exceeded the frieze of the ring hall in height. His metopes were decorated figuratively and showed the twelve deeds of Heracles in two six fields . Both parts of the frieze were made narrower than on the ring hall, and in the case of the metopes, they were only 1.43 meters. Pronaos and opisthodom could be closed with bars. One entered the cella through a 5.00 meter wide door, which could be closed by double-leaf bronze doors.

Whose bottom wall layer, which was formed on the outside of 1.75 meters high orthostats rested on a in the Ptera about 8 centimeters high Toichobat . Inside the cella, however, the visible height of the orthostats was only 1.14 meters, as the floor of the cella was around 60 centimeters higher than the peristasis pillars.

Two column positions each with seven Doric columns with a lower diameter of 1.50 meters divided the cella into three naves. These columns, which were about 3.50 meters apart, carried an architrave on which another, smaller column rose. Only this reached up to the roof structure and served to bridge the width of the cella with the wooden roof beams resting on it. Subsequently, the architrave seems to have served the construction of a gallery, which could be reached via spiral stairs on the side of the door. The relevant note from Pausanias was confirmed by the archaeological findings. The side aisles had a clear width of 1.47 meters, so they only formed a narrow corridor to approach the seated Zeus, which is about 13 meters high, from the side. Correspondingly, the cell height must be reconstructed somewhat higher.

Draft and curvature

Some basic design dimensions can be determined from the building report. A fundamental definition in the design of the Temple of Zeus was to give the ring hall a uniform yoke width on the long and narrow sides. In the design, however, this was slightly deviated from - by no more than about 1.5 cm with a yoke width of over 5.20 m. In the triglyph frieze (alternating triglyph and metope) the axis rhythm is doubled, a triglyph is arranged above the pillars and above the center of the yoke. In the geison it is doubled in that a mutulus is arranged above each triglyph and each metope. Finally, the marble roofing doubles the number of elements: eight rows of flat tiles are distributed over a pillar yoke. Halving can be observed as a central principle in the proportioning of the building. It can also be found in the floor plan, as the interior (the cella) is exactly half as long as the stylobate of the ring hall. Their central arrangement results in a scheme of 1: 2: 1. The strict order even extends to the arrangement of the sculptures in the gable, which they relate to the architectural structure in the triglyph frieze.

Which unit of measure the planning was based on is still controversial in research today. The so-called pheidonic foot, about 32.6 cm long, or a 32.04 cm long foot measurement, which so far has only been determined in Olympia and is therefore called the Olympic foot, comes into consideration.

The temple has a slight curvature , that is, all horizontal lines on the building, from the foundation to the roof edge, rise slightly from the corners to the center, on the front sides by about 4 centimeters. Thus no visible component of the temple fronts was damaged like a second.

The ratio of the number of front columns to long-side columns set at the temple of Zeus was trend-setting. At the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, the classical solution of Greek architects appears for the first time, which can be summarized in the formula “Front pillars: Flank pillars = n: (2n + 1)”. Numerous temples from the classical period followed, the layout of which was subject to this ratio.

Plastic jewelry

The pediment sculptures and the metopes are some of the most important surviving representatives of the strict style and are exhibited today in the Archaeological Museum in Olympia , two of the metopes are entirely in the Louvre , the greater part of a third metope.

gable

The pediments of the temple were decorated with sculptures made of Parian marble. A local legend - the race between Oinomaos and Pelops - is depicted as the theme in the east gable . Zeus appears in the middle as the fate determiner. The battle of the Lapiths against the Centaurs during the wedding of Peirithoos is shown in the west gable . The fate determining god is Apollo in this pediment . Many of the figures show clear signs of incompletion, some of them show clear features of a later period, which mark them as replacement pieces after repairs.

East gable

The theme of the east pediment is one of the central myths of Olympia: The race of Pelops against Oinomaos, the king of Pisa and thus also of Olympia. Oinomaos had received horses as fast as lightning from his father Ares and now, with a challenging certainty of victory, promised his daughter Hippodameia to the one who would defeat him in the chariot race. But the loser was threatened with death, just as Oinomaos himself threatened death according to an oracle from Delphi , if he would be defeated. After many suitors had to lose their lives, Pelops came to Pisa to face the task.

The multi-figure gable composition described by Pausanias picks up on the moment before the race. The arrangement of the figures has been disputed for more than a hundred years, as the figure fragments were scattered by stone robbers and early travelers. What is certain is that Zeus occupied the center of the composition. He stands still with his torso bared and turns slightly to his right. His judgment, the decision about victory, has long since been made. The viewer also knew the outcome of the story.

To the right of the god, according to Pausanias Oinomaos, stood next to him his wife Sterope , the daughter of Atlas. A team of four, in front of whom the Oinomaos' charioteer, Myrtilos , was kneeling, joined the end of the gable. Behind them another person, then an old man, probably Oinomaos's seer, and finally the river god of Kladeos , who flows into the Alpheios at Olympia .

On the other side of the god stood Pelops, followed by Hippodameia, then Pelops 'chariot team and a charioteer whose name, according to Pausanias' sources, was Sphairos or Killas. Two more people followed, the one on the right an old, bearded seer. In the gusset of the gable field again a stored river god, who turns his attention to what is happening in the middle. According to Pausanias, it is Alpheios .

The discussion of the arrangement initially arose around the question of whether Pausanias described the gable from the perspective of the figures or from the perspective of the beholder. On the basis of the river gods, one old and bearded and consequently the mature, tall Alpheios, the other youthful, i.e. the still young mountain river Kladeos, the question could be decided in favor of the observer. Topographically, too, the Alpheios flows south and the Kladeos north of the sanctuary and temple.

Contrary to the current arrangement of the gable figures in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia, Oinomaos stood on the right of the viewer, Pelops on the left of Zeus. Zeus turns to him, even if Pelops did not notice it. In the tense moment Zeus stands invisibly before the race that Pelops will win. The assignment of the female figures was and is still more controversial. The recurring question is: If the gesture of the one female figure, who is pulling a piece of her robe on her shoulder with her left hand, is to be interpreted as a bridal gesture or as a mark of the married woman, the delicately curled forehead of this female character characterizes those adorned for the wedding Bride or hairstyle is the hallmark of royal regalia, an imperious demeanor that is also reflected in the stiff demeanor. On the other hand: Should the propped head, the right arm carried in front of the chest and the almost dissolved robe of the other female figure represent the mourner, that is, the future widow? The actual tragic figure of the scene is Hippodameia, who will lose her father in order to have her husband.

Pausanias wrongly ascribes the figures on the east side to Paionios , from whose hand the acrotere of the front gable came, which is documented by inscriptions.

- East pediment of the Temple of Zeus

West gable

The composition of the west gable is agitated, moved, and also dramatic in action. Here, too, an invisible god dominates the field of view in the middle: the 3.15 meter tall Apollo of Olympia . The subject of the depiction is the battle of the Lapiths with the support of Theseus and Peirithoos against the Centaurs, who blissfully disturbed the marriage of Peirithoos with the Lapithin Hippodameia or Deidameia. In the Olympic context, Peirithoos is probably the son of Zeus, Theseus is a grandson of Pelops. Both conduct their fighting away from God in the direction of the gable gussets. Two groups of two follow on each side; first a centaur with an oppressed lapithin, then a centaur with a lapith, on the left in sexual approach, on the right biting a lapith in the arm. A group of three made up of a centaur, oppressed lapithin and lapith hurrying to help join on the left and right. The gussets are each filled by two watching Lapithesses. A raw, wildly agitated, swaying fight with biting and tearing and stinging, the outcome of which the god present has long since decided. While the ritualized battle in the form of chariot races was the subject of the east gable, the uncivilized battle of the mixed figures born from the clouds against the sex of the heroes is depicted here.

- West pediment of the Temple of Zeus

Metopes

Unusual for a Greek Doric temple is the attachment of relied metopes only to the entablature above the pronaos and opisthodom. Usually they adorn the triglyph friezes of the ring hall of a temple. The restriction to the twelve deeds of Heracles, whose myth is closely linked to the mythical story of the sanctuary in Olympia, may have been the reason for this solution. The so-called dodecathlos is distributed evenly over the six available metope fields and shows the act itself or an act of the associated narrative. Only two, in two cases three, participants are always united in one image field. The order of the metopes has been handed down by Pausanias, the metopes themselves and their fragments were found in mostly undocumented excavations from the early 19th century. The metopes uncovered by the French Expédition scientifique de Morée in 1829 are now in the Louvre in Paris .

East Side

Above the pronaos of the temple were from north to south the following actions to see Heracles:

Heracles as he starts in the presence of Athena, the stable of Augean muck. With a crowbar he is about to open the stable in order to guide the floods of the Alpheios and Peneios through the stable. With force, bent forward, the rear end of the handle of his tool reaches shoulder height. The reluctant diagonals of his body and tools are supported by Athena giving instructions with a staff.

This is followed by overcoming Kerberos , whom he pulls out of the underworld on a leash. The pulling of the Kerberos reflects the motif of movement of the Augias metope, although the hero here also pushes towards the center of the pronaos. Another person is present.

On the third metope, the universe rests quietly on Herakles' shoulders, protected by a pillow for relief, supported with a light hand by Athena standing behind him. The Atlas coming from the right brings him the golden apples of his daughters, the Hesperides . Heracles had shouldered the burden so that he could fetch her.

On the fourth metope, Heracles kills the three-bodied Geryoneus , whose most critical point in the depiction, where the three upper bodies grow out of the hip, is hidden behind a shield. The action of Herakles, who strikes a violent blow with his club, is oriented towards the center of the temple.

Herakles taming one of Diomedes' man-eating horses shows the fifth metope. Herakles standing frontally and in the center of the picture reins the horse charging towards the center of the frieze.

The sixth metope shows Eurystheus , who fled into a barrel and on whose behalf Heracles had to do his work. Heracles, coming from the left, with the Erymanthian boar on his shoulders, strides towards Eurystheus.

With the exception of the Geryoneus metope, which is part of the collection in the Louvre in Paris, all metopes on the east side are in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

- Three metopes from the east side of the Temple of Zeus

West side

Above the opisthodom of the temple, from south to north, the following deeds of Heracles could be seen:

Heracles fights against the queen of the Amazons, Hippolyte , who is stretched out on the ground , in order to take from her the belt, which the admete , the daughter of Eurystheus, desires for herself. The direction of movement of Heracles, like the reclining Amazon, is directed towards the center of the frieze. Hippolyte raises her shield in a last attempt to fend off the attack and blow of Heracles.

The next metope represents the overpowering of the Kerynite doe . Heracles had to hunt her for over a year, but has now forced her to the ground, pulls her head back and braces himself on her back with his right knee. The withdrawn head of the doe and Herakles moving obliquely to the left form two diagonals running in opposite directions in the composition, which is concentrated entirely on the center of the metope.

Restrained by a nose ring, Heracles leads the Cretan bull, still struggling and charging to the right, on the third metope. Conquered, but not yet completely overwhelmed, Heracles, pushing towards the center of the frieze, threatens him with a sweeping movement of his club. The metope is one of the three metopes that can be found in the Louvre in Paris today.

Also in the Louvre is the larger left part of the following metope. Heracles brings the dead stymphalic birds to Athena , which he could scare away with her help and kill with arrows. Athena, seated on a rock on the left, turns to Heracles, who has just arrived and is standing quietly on the right edge of the picture. While the metope part comprising Athena is now in the Louvre, Heracles, later found, is kept in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

The penultimate metope on the west side shows Heracles fighting the nine-headed hydra . In his right hand he holds the torch with which he burns out the stumps of the heads that have already been cut off in order to prevent the heads from growing back. His left foot tries to fix the struggling body of the monster.

Finally, the exhausted Heracles is shown in the sixth metope above the opisthodom. Heracles killed the Nemean lion and puts his right foot on the dead animal. Exhausted, he lays his head in the right hand of his arm resting on his knee, and with his left he leans on his club. Athena has come to him from the left, another god stands behind him.

- Three metopes from the west side of the Temple of Zeus

Cult statue

The Zeus statue by the sculptor Phidias , one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was located in the Temple of Zeus at Olympia . The width of the base and the interior of the temple allow the reconstruction of a 12 to 13 meter high statue. The foundations of the base were reinforced after the temple was completed, so they were not originally designed for a statue of the dimensions that were realized later. At the same time, the column arrangement inside the cella was slightly changed.

The Zeus statue was only introduced from 438 BC. BC, almost twenty years after the end of the construction of the temple , created by Phidias, who lived around 430 BC until the end of his life. Worked on this statue, one of his greatest masterpieces. The delay compared to the completion of the temple is due on the one hand to repair work after a severe earthquake in the 5th century BC. BC, but on the other hand it can also be due to the political situation in Greece after the end of the first Peloponnesian War .

Replicas of the statue or its parts have not survived. Numerous coin issues from the Roman Empire depict either the head or the entire statue of Zeus in profile or three-quarter view. Accordingly, Zeus was depicted sitting on a high throne. His feet rested on a stool. He held a winged Nike in his right hand and a propped up lance in his left hand. Sphinxes are shown below the back.

The Greek travel writer Pausanias gives a detailed description of the statue. The statue had a height of over 12 m, was clad in gold , ivory and ebony on the outside , so it was chryselephantine . His hair was long, and he wore a laurel wreath on it. The statue was decorated with reliefs and free sculptures. Painted barriers from the hand of Panainos , who was also responsible for the color design of the statue, kept the visitors at a distance.

Already in the 2nd century BC The statue must have suffered from the climatic conditions or the effects of earthquakes in such a way that a fundamental repair was necessary, which Damophon carried out. In 40 AD, the Roman Emperor Caligula failed in an attempt to bring the statue to Rome . The further fate of the statue is unknown.

literature

- Wilhelm Dörpfeld : The Temple of Zeus. In: Ernst Curtius , Friedrich Adler (Ed.): Olympia. The results of the excavation organized by the German Reich. Text volume 2: The architectural monuments. Berlin 1892, pp. 4-27 ( digitized version ); Volume 1, panels 8–17 ( digitized version ).

- William Bell Dinsmoor : An Archæological Earthquake at Olympia . In: American Journal of Archeology . Vol. 45, 1941, pp. 399-427.

- Alfred Mallwitz : Olympia and its buildings. Prestel, Munich 1972, pp. 211-234.

- Peter Grunauer : The Temple of Zeus in Olympia - New Aspects. In: Bonner Jahrbücher . Vol. 171, 1971, pp. 114-131.

- Peter Grunauer: The west gable of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The Munich reconstruction - structure and results . In: Yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute . Vol. 89, 1974, pp. 1-49.

- Peter Grunauer: The excavations at the Temple of Zeus in Olympia in autumn and winter 1977/1978 . In: Koldewey Society (Ed.): Report on the 30th conference for excavation science and building research 1978 in Colmar . o. O. 1980, p. 21-28 .

- Peter Grunauer: To the east view of the Zeus temple. In: Alfred Mallwitz (Ed.): 10th report on the excavations in Olympia. de Gruyter, Berlin 1981, pp. 256-301.

- Wolf Koenigs: The Temple of Zeus in the 19th and 20th centuries . In: Helmut Kyrieleis (Ed.): Olympia 1875–2000. 125 years of German excavations. International Symposium Berlin 2000 . Zabern, Mainz 2002, p. 131-146 .

- Arnd Hennemeyer: On the light effect at the Temple of Zeus Olympia . In: Peter Irenäus Schneider, Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt (Ed.): Light concepts in premodern architecture (= discussions on archaeological building research ). tape 10 . Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2011, p. 101-110 .

- Arnd Hennemeyer: The Temple of Zeus from Olympia. In: Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer u. a. (Ed.): Myth Olympia. Cult and games in antiquity. Prestel, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-7913-5212-1 , pp. 121-125.

- Arnd Hennemeyer: On the reconstruction of Phidias in the Temple of Zeus at Olympia . In: Architectura. Journal for the history of architecture . tape 43 , no. 1 , 2013, p. 1-18 .

- Arnd Hennemeyer: Continuity and Change. Observations at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia . In: Iris Gerlach, Dietrich Raue (eds.): Sanctuary and ritual. Holy places in archaeological evidence. (People - Cultures - Traditions) . Research cluster 4, vol. 10. Marie Leidorf, Rahden / Westf. 2013, p. 19-26 .

Web links

- Temple of Zeus, Olympia in the Arachne archaeological database

- Olympia, Temple of Zeus ( memento from April 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) on the website of the German Archaeological Institute .

Individual evidence

- ↑ A temple in Corinth that was previously discovered to be even larger based on a few remains did not reach the size of the Olympic Temple: Christopher Pfaff: Archaic Corinthian Architecture, approx. 600 to 400 BC In: Charles K. Williams II., Nancy Bookidis (ed.) : Corinth: Results of Excavations. Vol. 20: Corinth, the Centenary, 1896-1996. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton (NJ) 2003, p. 117.

- ↑ Pausanias 5, 10, 3: Λίβων ἐπιχώριος .

- ^ Pausanias 5:10 , 2.

- ↑ Pausanias 6:22 , 4; see. also Strabon 8, 362; Mait Kõiv: Early History of Elis and Pisa: Invented or Evolving Traditions? In: Klio . Vol. 95, 2013, pp. 315-368.

- ↑ Compare for example: Gisela MA Richter : The Sculpture and Sculptors of the Greeks. Yale University Press, New Haven (Conn.) 1967, p. 226; Burkhard Fehr : On the religious-political function of Athena Parthenos in the context of the Delisch-Attic League. In: Hephaistos 1, 1977, p. 73, note 38; Contrary to the general research opinion, the hypothesis was recently put forward that the building was a foundation of the Spartans and their allies: András Patay-Horváth: The builders of the Temple of Zeus. In: Hephaestus . Vol. 29, 2012, pp. 35-50.

- ↑ Werner Gauer : The Persian Wars and Classical Art. In: Egert Pöhlmann , Werner Gauer (Hrsg.): Greek Classical: Lectures at the interdisciplinary conference of the German Archaeological Association and the Mommsen Society from 24.27. – 10.1991 in Blaubeuren. H. Carl, Nürnberg 1993, p. 178.

- ↑ Arnd hen Meyer: The rebuilding of the Temple of Zeus Phidias in Olympia. In: architectura. Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Baukunst - Journal of the History of Architecture. Vol. 43, Issue 1, 2013, pp. 1-18.

- ^ A b Hans Schrader : The "substitute figures" in the west gable of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In: Annual books of the Austrian Archaeological Institute. Vol. 25, 1929, pp. 82-108.

- ↑ On the repair work of the 4th century BC See Arnd Hennemeyer: The restoration of the Temple of Zeus in classical times. In: Vinzenz Brinkmann (Hrsg.): Back to the classic. A new look at ancient Greece. Exhibition catalog Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt am Main 2013. Munich 2013, pp. 126–129; Arnd Hennemeyer: Continuity and Change. Observations at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In: Iris Gerlach - Dietrich Raue (Hrsg.): Sanctuary and ritual sacred places in archaeological evidence. Rahden / Westf. 2013, pp. 19–26.

- ↑ Already mentioned in Pausanias 5, 11, 10; on the cella of the temple see Arnd Hennemeyer: New results on the cella of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In: Report on the 43rd Conference on Excavation Science and Building Research of the Koldewey Society. May 19-23, 2004 in Dresden. Habelt, Bonn 2006, pp. 103–111.

- ^ Pausanias 5:10 , 5.

- ↑ Franz Willemsen : The lion's head gargoyles from the roof of the Temple of Zeus (= Olympic research 4). De Gruyter, Berlin 1959.

- ↑ Pausanias 5:10 , 3.

- ↑ Pausanias 5:10 , 4.

- ^ Pausanias 5:10 , 10.

- ↑ On the development of the floor plan, compare on the one hand Wolfgang Sonntagbauer: Einheitsjoch and stylobate measure. On the floor plans of the Temple of Zeus in Olympia and the Parthenon. In: BABESCH. Annual Papers on Mediterranean Archeology. Vol. 78, 2003, pp. 35-42; on the other hand Arnd Hennemeyer: The Zeus Temple of Olympia, in: W. Heilmeyer - N. Kaltsas - HJ Gehrke - GE Hatzi - S. Bocher (ed.), Myth of Olympia. Cult and games. Exhibition catalog Berlin (Munich 2012) pp. 120–125 (with pp. 448 and 452).

- ^ Peter Grunauer: The excavations at the Temple of Zeus in Olympia in autumn and winter 1977/1978 . In: Koldewey Society (Ed.): Report on the 30th conference for excavation science and building research 1978 in Colmar. o. O. 1980, pp. 21-28.

- ↑ Pausanias 5, 10, 6 f.

- ^ Wilhelm Dittenberger , Karl Purgold et al .: Olympia: the results of the excavation organized by the German Empire. Volume 5: The inscriptions from Olympia. Berlin 1896, pp. 377-384, especially p. 380.

- ^ Pausanias 5:10 , 9.

- ↑ On the cella of the temple and base see Arnd Hennemeyer: New results on the cella of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In: Report on the 43rd Conference on Excavation Science and Building Research of the Koldewey Society. May 19-23, 2004 in Dresden. Habelt, Bonn 2006, pp. 103–111.

- ↑ Ulrich Sinn : The ancient Olympia. Gods, games and art. 3rd edition, CH Beck, Munich 2004, p. 213.

- ↑ Arnd hen Meyer: The Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In: Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer u. a. (Ed.): Myth Olympia. Cult and games in antiquity. Prestel, Munich 2012, pp. 121–125.

- ↑ For example András Patay-Horváth: The builders of the Temple of Zeus. In: Hephaestus . Vol. 29, 2012, pp. 35-50, here p. 48 f.

- ↑ Hans Schrader : The Zeusbild of Phidias in Olympia. In: Yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute. Vol. 56, 1941, pp. 1-71, here pp. 5-10 and passim; Josef Liegle: The Zeus of Phidias. Pp. 318-332.

- ^ Pausanias 5:11 , 1-11.

- ^ Pausanias 4, 31, 6.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus , Antiquitates Judaicae 19, 8-10; Suetonius , Caligula 22, 2 and 22, 57; Cassius Dio 59, 2-4.

Coordinates: 37 ° 38 ′ 16.3 " N , 21 ° 37 ′ 48" E