Northern Patrol (First and Second World War)

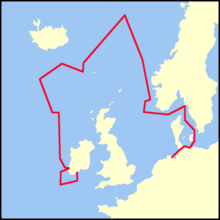

The Northern Patrol was a Royal Navy operation conducted from August 3, 1914 to November 29, 1917 during World War I. The task was the sea blockade of Germany in the north-eastern Atlantic in the triangle of Scotland , Lofoten and Iceland . The southern counterpart was the Dover Patrol in the English Channel . Anglo-American naval historians see their work as the decisive factor for the defeat of the Central Powers , as indirect warfare wore down the German home front and triggered social unrest up to the November Revolution. The operation was terminated at the end of 1917, when the United States entered the war in April 1917 and the states were no longer trading partners of the Reich. The operation resumed at the beginning of World War II , but was de facto ended in September 1940 due to its strategic location in Northern Europe.

Strategic goal setting, organization

The main objective of the blockade and thus the activity of the Northern Patrol was to prevent the importation of goods of all kinds from neutral countries overseas, especially the USA and the South American states, into Germany. Conversely, the export of German goods should be prevented. Although the blockade was also intended to prevent the operations of German auxiliary cruisers and submarines to wage the cruiser war in the Atlantic and overseas, this remained a secondary aspect.

Therefore, if possible, all neutral trade shipping should be controlled. This often required an inspection of the merchant steamers and, in this epoch, numerous sailing ships still in use by armed commandos, which was carried out with dinghies . If contraband was suspected , the ships concerned were escorted to British ports. Often, however, the blockade units were content with inquiring about their origin and destination, as in the case of the Chilean- German refugee Tinto (see below).

On July 29, 1914, the Admiralty had given the order to prepare for war. The Northern Patrol was part of the Grand Fleet and was under the Admiral Commanding, Orkneys and Shetlands. On August 1 hoisted Rear Admiral Dudley de Chair (1864-1958) under its flag on the battleship HMS Crescent of Edgar class as a flagship of the 10th Cruiser Squadron (10th Cruiser Squadron). In 1913, the 11th Cruiser Squadron had been planned for an emergency, but this now served as Cruiser Force E in Ireland ( Queenstown ) and in the Persian Gulf. On August 7th, the squadron was ready for action and traded as Cruiser Force B.

The 10th Cruiser Squadron consisted of the eight Edgar-class armored cruisers that had entered service at the beginning of the 1890s and were primarily intended for colonial service and operations in the context of gunboat policy . HMS Crescent itself had served in the South Seas and the West Indies . For permanent use on the high seas, especially under the extreme weather conditions of the North Atlantic including the occurrence of monster waves , they were neither intended by their design nor, as was to become apparent at the beginning of autumn 1914, suitable. They were therefore replaced by auxiliary cruisers in December 1914 (AMC = Armed Merchant Cruisers = armed trade cruisers). These were usually passenger steamers that operated ferry traffic between Great Britain and Norway in peacetime, as well as banana carriers , which were particularly suitable for the pursuit of potential blockade breakers due to their high speed . The passenger steamers also offered the advantage of spacious accommodation, so that the crews could be accommodated in cabins. The high proportion of former banana freighters in the squadron led to the nickname "Banana Fleet" or simply "Bananas". Basically, the Northern Patrol operated from the Shetland Islands, where de Chair set up a base in St. Magnus Bay .

The replacement of the armored cruisers had also become necessary because the sinking of the HMS Hawke by SM U 9 on October 15, 1914 had proven that the old cruisers were so slow due to their age and poorly maintained machines that they were prey for the submarines could serve. On November 11th, HMS Crescent got caught in a storm in which a monster wave swept over the forecastle and completely destroyed de Chair's sea cabin. In addition, the sea tore a whale boat out of its davits , seawater seeped into the boiler rooms and put out some fires. The waves reached heights of 50 feet and de Chair at times had doubts as to whether the flagship would survive the storm.

As early as August 1914, the auxiliary cruisers Alsatian (later Empress of France ), Mantua and Teutonic had joined the cruiser squadron. On December 4, 1914, de Chair hoisted his flag on the Alsatian . The armored cruisers were released. In July 1915, 24 auxiliary cruisers with 7,330 crew members served in the patrol. The Alsatian had covered around 36,000 nautical miles from December 1914 to July 1915, consuming around 21,000 tons of coal. The squadron was consuming 1,600 tons of coal a day at that time. In addition to the three units mentioned above, the following auxiliary cruisers were used:

- Patia

- Patuca

- Bayano

- Motagua

- Changuinola

- Ambrose

- Hilary

- Hildebrand

- Carribbean (ex Dunottar Castle )

- Oratava

- Eskimo

- Calypso (later Calyx )

- Oropesa (later French Champagne )

- Digby (later French Artois )

- Columbia (later HMS Columbella )

- Viking (later HMS Viknor )

- Clan McNaughton

The auxiliary cruisers had a size between 2800 and 8200 tons and belonged to different shipping companies . Apart from a hull crew of the Navy, in particular the Royal Marines, the crews consisted almost exclusively of reservists from the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) and volunteers from the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR), preferably from the seafaring population to Newfoundlands and New Zealanders.

activity

The blockade units did not operate within sight, but at a distance of around 20 nautical miles. With an assumed visibility of 15 nautical miles, it was assumed that blockade breakers would be sighted by at least one of the two units. This assumption was, however, given the weather conditions in the area of operations, especially in winter and especially at night, purely theoretical. The weather presented itself for the extremely seaworthy auxiliary cruiser a challenge, in particular by the installation of guns that are dangerous to the Topplastigkeit the Ships. For example, some squadron officers attributed the downfall of Clan Macnaughton with the entire crew of 251 men on February 2, 1915 north of Ireland to precisely this circumstance.

Apparently due to the first breakthrough of the auxiliary cruiser SMS Möve (see below), fleet chief Admiral Sir John Jellicoe ordered a considerable reinforcement of the patrol in March 1916 with armored cruisers of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron: HMS Minotaur , Shannon , Achilles , Cochrane and Duke of Edinburgh . Later, armed fish steamers analogous to the German outpost boats were used for patrol service. De Chair was replaced by Vice Admiral Reginald Tupper (1859-1945), who led the operation to its conclusion in November 1917.

When the USA entered the war in April 1917, the remote blockade of the Northern Patrol began to become superfluous. The first units for convoy protection were sent to the USA in April . At the end of July there was a further reduction in forces. Finally, only the Alsatian , Teutonic and Orvieto were in service until the Northern Patrol was discontinued on November 29, 1917. In a certain sense, it was replaced by the North Sea mine lock from March 1918 , which, however, was directed exclusively against the operations of German submarines in the Atlantic.

During the activity of the patrol

- stopped and examined at sea: 12,979 vehicles,

- volunteered to be examined in British ports: 2,039 vehicles,

- were sent to ports for investigation with an armed team: 1,816 vehicles,

- escaped the blockade units, as far as this could be registered: 642 vehicles,

- German surface units were placed and sunk: two auxiliary cruisers (see below).

In the service of the Northern Patrol, the armored cruiser HMS Hawke (see above) and seven auxiliary cruisers sank either through submarines or sea mines . Two auxiliary cruisers allegedly sank due to the weather conditions. 16 merchant ships, which went with escort crews of the patrol, were apparently sunk by submarines, several other merchant ships were shot at by them. The total personnel losses amounted to 103 officers and 1,063 NCOs and men.

For purely foreign policy reasons vis-à-vis the USA, two French units were also deployed, the Artois (ex Digby ) and Champagne (ex Oropesa ). Their use was of no tactical significance. The Champagne was sunk in the Irish Sea on October 9, 1917 by a German submarine, with 56 crew members falling.

Breakthrough of German auxiliary cruisers and auxiliary ships, commercial submarine Germany

Despite relatively close monitoring, the auxiliary cruisers SMS Meteor , SMS Möve , SMS Wolf and SMS Seeadler - in the case of the Möve on two voyages - managed to break through the blockade on the outbound and return journeys. On the other hand, the auxiliary cruisers SMS Leopard and SMS Greif were placed in the attempt to break through and sunk after fighting. The Möve - Prize Yarrowdale (later SMS Leopard , see above) had also passed the blockade line towards Germany unnoticed.

In addition, under the legend of neutral or British merchant ships, the auxiliary ships Rubens , Marie and Libau achieved their breakthrough in 1915/16 with the aim of transporting weapons and equipment for the protection force for German East Africa and the rebels in the Irish Easter Rising . The merchant submarine Germany was also able to break the blockade on both voyages to the USA. Already in November / December 1914 the auxiliary ship Rio Negro , a supplier of the small cruiser SMS Karlsruhe , which sank off Trinidad , broke through the blockade coming from South America.

The sinking of the auxiliary cruisers Greif and Leopard was possibly less successful due to the actual activity of the blockade forces than the monitoring of German radio traffic through Room 40 and / or British agent reports from Germany, which announced the time of the planned breakthrough. The sea eagle was checked by the blocking forces, but due to the legend it was not revealed as Norwegian. However, this representation is based solely on the memoirs of their commanding officer Felix Graf Luckner and is strongly doubted by Hampshire, as there is no evidence for this process on the British side. (Hampshire, "The Blockaders," p. 80)

The Chilean-German escape barge Tinto , which broke through to Norway under the Norwegian legend Eva , was stopped on March 23, 1917 by the auxiliary cruiser Dundee and the armored cruiser HMS Shannon and asked about its origin and destination by signals. The answer was accepted, especially since the weather conditions were extremely bad and there was no direct control of the ship. When the breakthrough was published in the Frankfurter Zeitung on April 13, 1917 , the news caused outrage in the Admiralty and the blockade forces were instructed to search all intercepted ships regardless of weather conditions.

Results

The British military historian Basil Liddell Hart assessed the effectiveness of the blockade and thus the activity of the Northern Patrol as follows:

Just as the straitjackets were once used in some American prisons to bring rebellious prisoners to reason, so the blockade first restricted the prisoner's freedom of movement, then choked his breath, and the longer it lasted, the more the prisoner's resistance waned the consciousness of being trapped became all the more devastating.

Liddell Hart, Strategy , p. 244.

Furthermore, Hart stated that the collapse of Bulgaria and the threat to Austria-Hungary as well as the moral effects of the blockade “acted like two spurs on the hungry people, with which the German government was driven to surrender”. (Ibid., P. 261f.)

This view is also shared by Eric W. Osborne in his study on blockade, reproduced by Spencer C. Tucker :

The blockade brought economic ruin and widespread unrest in Germany and was thus an important factor in forcing Berlin to seek for peace. The blockade was only terminated on 12 July 1919, when the Allied powers received word that the German government had ratified the Treaty of Versailles… British naval blockade was the greatest factor in the defeat of Germany in World War I.

Osborne, Blockade, British of Germany, World War I , in: Tucker (ed.): Naval Warfare. An International Encyclopedia , pp. 132f.

Second World War

On September 6, 1939, the Northern Patrol was re-established. As 25 years before, regular units served in it first until they were replaced or supported by auxiliary cruisers. The blockade area now extended to the waters north of Ireland and the Denmark Strait . The flagship was the cruiser HMS Effingham . The 7th, 12th and 11th cruiser squadrons were used. Commanders were Admiral Max Kennedy Horton and Rear Admiral Ernest John Spooner. At least in theory, the blockade was supported by Royal Air Force aircraft .

Due to the German occupation of Norway, the Netherlands , Belgium and France, German shipping and the navy had, at least in theory, an operating room from the North Cape to Spain ; a completely different maritime strategic situation compared to the First World War. As a result, the Northern Patrol was practically set in September 1940 and assigned its units to the Western Patrol, which operated mainly in the mid-Atlantic.

literature

- Steve Dunn: Blockade. Cruiser Warfare and the Starvation of Germany in World War One , Barnsley 2016. ISBN 978-1-84832-340-7

- A. Cecil Hampshire: The Blockaders , London 1980. ISBN 0-7183-0227-3

- Eric W. Osborne: Blockade, British of Germany, World War I , in: Spencer C. Tucker: Naval Warfare. An International Encyclopedia , Santa Barbara, CA, 3 Vols., Vol. I, pp. 132f.

- Eric W. Osborne: Great Britain's Economic Blockade of Germany in World War I, 1914–1919 , London 2004.

- John D. Grainger (ed.): The maritime blockade of Germany in the Great War. The Northern Patrol, 1914-1918 , Aldershot et al. a. (Ashgate) 2003. ISBN 0-7546-3536-8

- Elmar B. Potter / Chester W. Nimitz : Sea power. A history of naval warfare from antiquity to the present . German version published on behalf of the Working Group for Defense Research by Jürgen Rohwer , Herrsching 1982. ISBN 3-88199-082-8

- Basil H. Liddell Hart: Strategy , Wiesbaden (Rheinische Verlagsanstalt) undated (1955).

- Paul G. Halpern: A naval history of World War I , Annapolis, MD (Naval Institute Press) 1994, p. 48ff. ISBN 0-87021-266-4

- Chapter 6: "A barbaric rawness without equal": blockade, submarine war and the struggle for American neutrality , in: Holger Afflerbach : Auf Messers Schneide. How the German Reich lost the First World War , Munich 2018, pp. 137–159. ISBN 978-3-406-71969-1