Libau (ship, 1911)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

The Libau was built as a Castro in England. It was captured by Germany in the Kiel Canal at the beginning of the First World War and renamed Libau . Disguised as the Norwegian ship Aud , she was a blockade breaker of the Imperial Navy , who was sent to the west coast of Ireland in April 1916 under Lieutenant to the Sea of the Reserve Karl Spindler to deliver a load of weapons and explosives for the participants in the Irish Easter Rising .

The enterprise was carried out by the intelligence service of the Admiralstab , the German naval intelligence service . Due to communication deficits , the Libau in Fenit Harbor in Tralee Bay was not picked up by the rebels. While fleeing from guard vehicles of the Royal Navy , the Libau was self- sunk by its crew off Queenstown on April 22, 1916 . The crew fell into British captivity . Together with the steamers Rubens , Marie and Equity , the Libau was one of four auxiliary ships that were used during the First World War by the intelligence service of the Admiral's staff for secret weapons transports abroad.

Use as a blockade breaker

Planning

On November 8, 1915, the General Staff asked the Admiral Staff whether the Navy would be able to carry out a larger arms transport by sea to Ireland. The trigger for the request was the report of a German secret agent in New York , who had contacts with the local Irish underground movement around John Devoy (1842–1928), who had been planning the armed uprising in Ireland for decades with the Irish Republican Brotherhood . The General Staff was an absolute proponent of an Irish revolution . He speculated that an uprising would force the British side to send massive troops to the island, and hoped that this would relieve the German western front .

The Navy was skeptical of the company from the start. Serious logistical difficulties as well as concerns about possible treason on the part of the Irish spoke against such an operation. The use of submarines was out of the question due to their insufficient loading capacity. In addition, because of the ongoing submarine warfare , the boats were practically indispensable and, in the opinion of the Navy, should not be put at risk for questionable intelligence operations.

The command of the ocean-going fleet in Wilhelmshaven then prepared an expertise at the end of 1915. Thereafter, three British fish steamers confiscated in Germany when the war broke out and lying in Geestemünde were to be used for transport. British prisoners of war of Irish origin were proposed as the crew, who would eventually make themselves available for the company to support the uprising.

This plan had the advantage that the ships and their crews could remain in Ireland, thus avoiding another breakthrough through the British North Sea blockade . However, when the trawlers were examined in Geestemünde, it turned out that they could only transport 6,000 of the 20,000 rifles planned.

But it was not until the end of February / beginning of March 1916 that the Admiralty's staff received certain information that a major Irish uprising was actually supposed to take place at Easter. At the same time, the Irish politician in exile, Sir Roger Casement , who resided in Germany, reported to the Admiral's staff and offered to accompany a possible transport of weapons on a submarine. By March 13, 1916, it was definitely clear that the uprising should be carried out. However, Casement planned to persuade the leaders of the uprising in Dublin to abandon the company, as he considered an armed rebellion to be completely hopeless due to the general conditions.

On March 17, 1916, the central meeting for the implementation of the company with the most important representatives of the Admiral Staff , the command of the high seas, the Reichsmarineamt and the naval station of the North Sea took place at the Admiral Staff in Berlin . The intelligence service of the Admiral's staff was represented by Lieutenant Captain Egon Kirchheim of the Maritime Defense Reserve; he was responsible for the operational management of the company.

Kirchheim informed the conference participants that the use of fish steamers was excluded. Instead, a small steamer was provided, which should be of British origin for camouflage reasons. Obtaining such a vehicle was not a problem, as numerous British merchant ships had been confiscated in German waters when the war broke out.

Immediately thereafter, the British Castro , which was available in Hamburg, was taken over for the company and immediately repaired in Wilhelmshaven. The ship was then moved to the Baltic Sea through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal . The entire crew of the now renamed Libau steamer consisted of reservists and members of the naval service . The commandant, lieutenant at sea of the reserve Karl Spindler, was an experienced navigator and officer in the merchant navy .

The name Libau itself was a diversionary maneuver towards both navy personnel and suspected spies ; allegedly the steamer was intended for transport tasks for a German company in occupied Libau , then Kurland , now Latvia .

The ride of the Libau

On April 9, 1916, the Libau ran from Warnemünde to Fenit Harbor, today part of the city of Tralee . The charge consisted of 20,000 Russian booty rifles of the Mosin-Nagant type and ten Russian Maxim type machine guns including ammunition and apparently 400 kg of explosives for sabotage purposes. Contrary to later British propaganda reports, the rifles were practically brand new and came from arsenals in Russian Poland that had been captured during the German advance on the Eastern Front .

As an auxiliary ship, the Libau itself was unarmed and had no radio telegraphy , which was common at the time for commercial steamers of their small size. A radio system was not necessary either, since it was a pure transport company and the insurgents did not have radio systems anyway. The steamer was supposed to meet U 19 in Tralee Bay , who was transporting Casement and two companions.

But the encounter with the submarine was of no relevance for the transport of weapons. April 20-23, 1916 was planned as the time slot for the handover of the weapons. It was unclear, however, how the steamer would cross the coast for up to three days without being noticed by British guards. It was also unclear how the cargo should be unloaded, because technically this was only possible at the Fenit Harbor pier . However, this presupposed that the port was already in the hands of the rebels when they landed.

After leaving Warnemünde, the Libau was camouflaged as the Norwegian steamer Aud and the Norwegian flag and name of the ship were painted on port and starboard . The real Aud , 1907 in Bergen from running stack was 1,102 t size slightly smaller than the Libau , but saw their outwardly quite similar. To cover the camouflage, Spindler had forged ship's papers and the entire crew had Norwegian legends . The Aud itself was according to legend, on the way to Genoa .

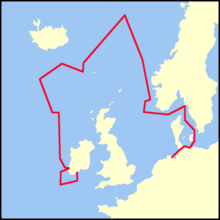

The eleven-day voyage of the Libau first led closely along the Norwegian coast north to break the British blockade line. At the height of Iceland she turned south and broke halfway between Iceland and the Faroe Islands into the North Atlantic , passed Rockall and headed for the Irish west coast. On the voyage she met several British auxiliary cruisers , but they were not suspicious. However, this sea route was heavily frequented by ships to and from the neutral states of Norway , Denmark and Sweden ; In addition, during the Libau voyage the weather was mostly stormy, so that the guard vehicles were severely hampered in their control activities.

The Liepaja came just before the end of the ride in a hurricane , in which part was her deck cargo of wood overboard. But she arrived safely in Tralee Bay on the afternoon of April 20, 1916, which is also confirmed by reports from British guards who immediately sighted the ship. According to orders, Spindler was to be in Tralee Bay until April 23, 1916 to hand over the weapons. Thereafter, he was free to enter the port or return to Germany at his own discretion. In an emergency, he was left to call at a neutral port in Norway or Denmark. This also applied to the successful handover of the weapons and any complications with British guard vehicles on the return journey.

As a further option, Spindler was open to using his ship as a trade cruiser after unloading his cargo and to go hunting for enemy merchant ships in the Atlantic. That was the plan that the commandant wanted to implement. He had received the permission of his superiors for this and had already carried out the light retrofitting of the Libau for it a day before arriving in Tralee Bay . For example, four 10.5 cm guns were built from wood for installation on deck, of which the opponent could not have known from their view that they were only dummies, and similar deception measures had been prepared to use the A ruse to make the unarmed freighter appear as a warship that a merchant ship would not offer any resistance.

Transport of casement

Casement and two companions had traveled by train from Berlin to Wilhelmshaven and embarked there on April 12, 1916 on U 20 under Lieutenant Walther Schwieger . However, one and a half days after departure, U 20 suffered an accident on the down rudder , which forced Commander Schwieger to call at Heligoland . On Heligoland there was a flying change to U 19 under Oberleutnant zur See Raimund Weisbach , who took over the three passengers.

Inexplicably, Schwieger allegedly did not hand over the original order, but only gave Weisbach, who had been a watch officer on U 20 until a few days earlier , the details, especially the planned handover time, orally. Allegedly, Schwieger had already destroyed the original order for security reasons. It is certain only that U 19 the Liepaja on the night of 21 April 1916 in front of the island , not finding Inishtooskert in the Tralee Bay and Casement and his companions at his own request with a dinghy exposed on the coast. Casement was arrested by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) on the morning of April 21 . He was executed in London on August 3, 1916 after a trial in which he was charged and convicted of treason, sabotage and espionage .

The sinking of the Libau

For Spindler, the encounter with the submarine and contact with Casement in connection with his actual task were of no importance. An agreement had been reached with the rebels through contacts in the USA that a pilot vehicle should be available in the bay between April 20 and 23.

In fact, the 19-year-old Mortimer “Murt” O'Leary was the pilot who had already identified the Libau as Aud on the day of her arrival in Tralee Bay, April 20, 1916. But O'Leary had no information about the appearance of the expected ship. In addition, he and his senior officers expected the arrival of one or more transporters at the earliest on April 23, 1916, the day before Easter Sunday as the date of the uprising. He also had strict instructions not to contact any other ship before that date.

O'Leary also did not rule out that the alleged Aud was possibly a British submarine trap , a so-called Q-ship , which also operated in western Irish waters. He was therefore afraid of being exposed by the British when the alleged Aud was addressed ; therefore no contact was made. The cause of this lack of communication lay in the complicated communications links between John Devoy in the United States, the insurgent leaders in Ireland, and the link between Devoy and the General Staff and then the Navy.

Spindler's position in Tralee Bay became untenable as early as April 21, 1916 when it was checked by the British guard vehicle Setter II , a former fishing cutter. Although Spindler succeeded in deceiving his commanders, he realized that any further stay in Tralee Bay would inevitably lead to exposure, as the commander himself informed him that a German weapons ship was expected.

Immediately afterwards Spindler spotted another guard vehicle, the war trawler Lord Heneage , who, unlike Setter II, also had radio telegraphy and clear instructions to check the Norwegian, who had meanwhile been classified as suspicious by guards ashore. In addition, the RIC had meanwhile found the dinghy with which Casement and his companions had come ashore and immediately reported this to the Royal Navy, since it was now clear that either a German submarine or a surface ship was off the coast had to. In any case, the British Admiralty had known since March that one or more German weapons transports were to be deployed to Ireland, only they had no information about the character of the ship or ships themselves.

Around noon on April 21, 1916, the Libau left the bay with the utmost strength in order to evade control by Lord Heneage . The trawler reported by radio to other units of the Royal Navy operating off the coast that the suspect vehicle had escaped, and the Libau was intercepted by the sloop Bluebell at 6.15 p.m. on April 21, 1916 .

But Spindler did not give up hope of escape. He speculated that the Bluebell would translate a prize squad and then move away to take on further guard duties in the submarine war. Overcoming the command would not have been a problem for the Libau crew, as the handguns required for this had already been placed in selected places. But the region's commanding admiral , Sir Lewis Bayly, expected such a plan and expressly forbade the Bluebell commander to send a prize squad by radio.

Spindler was instructed by a warning shot and signals from the Bluebell to enter Queenstown. In this situation he only had to sink himself in order not to let the weapon load, which is also valuable for the British side, fall into their hands. On Saturday, April 22, 1916, at 9:28 am, the Libau crew detonated explosive cartridges near the Daunt Rock lightship ( 51 ° 43 ′ 30 ″ N , 8 ° 17 ′ 30 ″ W ) southeast of Queenstown ; at 9.40 a.m. the ship sank. The men got into the boats in good time, were picked up by the Bluebell shortly afterwards and were taken prisoner of war.

The whereabouts of the crew and consequences

The crew were transported to England and interrogated at Scotland Yard by Admiral William Reginald Hall . “Blinker” Hall was Director of Naval Intelligence (DNI) from 1914 to 1919 , and was also responsible for the decryption department, internally called Room 40 . After the interrogations, the crew was distributed to various POW camps; Spindler to Donington Hall . The crew and officers were finally interned in the Netherlands against giving their word of honor .

Spindler published his memoirs as early as 1921: The mysterious ship. Blockade breakthrough SM auxiliary cruiser "Libau" for the Irish revolution ; At the same time, the English version appeared under the title: Gun Running for Casement , which ten years later under the title: The Mystery of the Casement Ship. With authentic documents by the commander of the "Aud" , was re-edited. The work has been translated into several languages. Spindler's statements are largely correct, as has meanwhile been established through the examination of British sources. In fact, the auxiliary ship had a purely transport task and was never intended for the cruiser war by the Admiralty and was therefore not armed. Spindler wrote in his memoir that he had intended to wage a trade war in the Atlantic after completing his assignment. Appropriate permission had been given to him. Accordingly, one of the machine guns in the load should remain on board. Small merchant ships were to be stopped by wooden artillery dummies , firecrackers and machine gun fire. It is only in the subtitle of the book on the inside pages that the blockade breakthrough SM auxiliary cruiser "Libau" for the Irish revolution is called . After that would be S a M ajestät auxiliary cruiser from the beginning of his journey on a warship was what it would have become only after setting the battle flag, with its purely military occupation. In fact, the Libau went down with the war flag set.

Spindler stayed in the Reichsmarine after 1918 and emigrated to the USA in the early 1930s.

For the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising in 1966, the Irish government invited surviving members of the Libau and U 19 crew . The former stokers Jans Dunker (1891–1978) and Friedrich Schmitz (1892–1977) as well as the former machinist's mate Wilhelm Augustin (1890–1972) traveled from Libau to Ireland, from U 19 Weisbach and his former first officer Otto Walter ( 1891–1972) 1972), and took part in the celebrations.

The wreck

The wreck of the Libau was examined several times in May / June 1916 by British divers who recovered some rifles, ammunition, two explosives and equipment. This also included the Libau's Imperial War Flag , which was hoisted when it was scuttled to document its character as a war vehicle. This flag is now in the Imperial War Museum in London.

The wreck of the Libau was displaced by the current ; at times his position was unknown. It was found again in 1974 by the diver John Kelleher. On June 16, 2006, a plaque was attached to the wreck on the 90th anniversary of the Easter Rising by the diver Ian Kelleher to commemorate the voyage of the Libau . It bears the inscription:

In Remembrance of Sir Roger Casement ,

Captain Spindler and the Crew of the AUD .

Men who in 1916 risked / lost their lives for Irish Liberty .

Thank you all

The wreck of the Libau is the property of the Federal Republic of Germany , as the German Embassy in Dublin confirmed in a letter to the Irish author George Alexander Clayton on March 23, 2006. Clayton's 900-page work AUD , which appeared in Plymouth in 2007 , is based on meticulous research in Great Britain , Germany, Ireland and the United States and currently represents the state of research on the history of Libau and its involvement in the Easter Rising.

The real name of the Libau had been forgotten even in Germany 50 years after its demise. When the Nordwest-Zeitung in Oldenburg reported in its April 12, 1966 edition about the participation of the five German war veterans in the Irish celebrations, Libau was consistently incorrectly referred to as Aud .

On June 19, 2012, divers Eoin McGarry and Laurence Dunne recovered two anchors from a depth of 36 meters , which are to be exhibited to the public after the restoration.

The fate of the real Aud

The real Aud , like her alias, was also a victim of the First World War. It was stopped and examined on November 30, 1916 under Captain Andreas Stehen from Bergen by UB 18 under Kapitänleutnant Claus Lafrenz on a coal transport from Cardiff to Lisbon north of Cornwall . Lafrenz declared the charge to be contraband ; the crew then had to leave the ship in the lifeboats. The Aud was blown up with explosive cartridges and taken under gunfire to speed up the sinking. She sank nine nautical miles northwest of Godrevy Lighthouse . Her crew was taken up shortly afterwards by the Spanish steamer Alu Mendi under captain J. De Foran from Bilbao , who had also been stopped by UB 18 , but was released, and returned safely to Norway.

Movies

- Sir Roger Casement (TV-ZDF 1968, director: Hermann Kugelstadt ). The journey of the Libau is detailed in this documentary game.

See also

- Bombardment of Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth on 24./25. April 1916

literature

- Caught casement. In: News for town and country . Oldenburger Zeitung for people and homeland. of April 28, 1916, ZDB -ID 2127432-0 .

- Karl Spindler : The mysterious ship. The trip of the "Libau" to the Irish Revolution. Scherl, Berlin 1921 (At the same time, the English edition appeared under the title: Gun Running for Casement. W. Collins Sons, London 1921, which ten years later under the title: The Mystery of the Casement Ship. With authentic documents. By the commander of the "Aud". Kribe, Berlin 1931. Another edition appeared in Tralee, Anvil Books, in 1965 with an introductory foreword by former IRA intelligence officer Florence O'Donoghue. Other editions: Le Vaisseau Fantome. Episode du complot de Sir Roger Casement et de la révolte irlandaise de pâques 1916. Payot, Paris 1929. El Buque Fantasma. Joaquín Gili, Barcelona 1930. Сквозь блокаду. ( breach of the blockade ). Leningrad 1925, new edition: Понт Эвксинссий, Moscow 1997) .кий, Moscow 1997).

- Otto Groos: The War in the North Sea. Volume 5: From January 1916 to June 1916. Marine-Archiv, Berlin 1925, pp. 113–158.

- Florence O'Donoghue: The Failure of the German Arms Landing at Easter 1916. In: Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society. Vol. 71, 1966, ISSN 0010-8731 , pp. 49-61.

- John de Courcy Ireland: The Sea and the Easter Rising. Maritime Institute of Ireland, Dublin 1966 (New editions: FBS, Philadelphia PA 1982; Revised and enlarged edition. Dun Laoghaire, Dublin 1996, ISBN 0-00-000258-5 ).

- Irish celebrate independence. Commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Easter uprising. In: Nordwest-Zeitung. of April 12, 1966, ZDB -ID 1013877-8 .

- Patrick Beesly: Room 40. British Naval Intelligence 1914-18. Hamilton, London 1982, ISBN 0-241-10864-0 .

- Paul G. Halpern: A Naval History of World War I. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD 1994, ISBN 0-87021-266-4 .

- Reinhard Doerries: Prelude to the Easter Rising. Sir Roger Casement and imperial Germany. Frank Cass, London et al. 2000, ISBN 0-7146-5003-X .

- Xander Clayton (di: George Alexander Clayton): AUD. GAC, Plymouth 2007, ISBN 978-0-9555622-0-4 .

- Cord Eberspächer, Gerhard Wiechmann: “Success revolution can decide war”. The use of SMH LIBAU in the Irish Easter Rising of 1916. In: Schiff & Zeit. Panorama maritime . Vol. 67, Spring 2008, ISSN 1432-7880 , pp. 2-16.

Web links

- Sir Roger Casement

- Anchors recovered from arms-smuggling vessel scuttled in plan to aid Easter Rising, in: The Irish Times of June 20, 2012