Regulatory Affairs

A drug approval is an officially issued approval that is required in order to be able to offer, sell or dispense an industrially produced, ready-to-use drug . A drug approval is only ever granted for a specific indication (ie an application area). The use of an approved drug outside of the approved indication is called off-label use .

Purpose of the procedure

The purpose of an authorization procedure for substances and preparations as medicinal products is risk prevention and protection against health hazards that could arise from unsafe or ineffective medicinal products. As part of the approval process , documents submitted by the pharmaceutical company on the pharmaceutical quality, therapeutic efficacy and safety of the drug are therefore checked by drug authorities; the information in the documents is checked by on-site inspections.

Effects of approval

The granted approval certifies that the drug is marketable and may be brought onto the market, i.e. that it can be offered in pharmacies , for example. For doctors, the approval is proof that the drug has been tested for a positive risk-benefit ratio in the indicated indication . The granted approval has other effects as well.

As a rule, the drug approval is a prerequisite for the social law supply ability. In many countries there are also other social law approval procedures that are independent of drug approval and represent an additional prerequisite for reimbursement of drug costs by health insurance companies . These regulations differ from country to country, they often include binding price fixing and can delay market access by several months.

In addition, in some countries there are special liability regulations for approved drugs. In Germany there is a special strict liability on the basis of § 84 AMG, according to which the pharmaceutical company has to pay damages in the event of damage caused by drugs that were used as intended. This applies to both manufacturing and development errors. In contrast to liability under the German Civil Code , the injured party does not have to prove the causality between the application and the damage incurred. This liability does not apply to off-label use. In contrast to Germany, Austria has not introduced any special strict liability in its Medicines Act.

A valid approval is also necessary in the EU for issuing a supplementary protection certificate in accordance with Regulation (EEC) No. 469/2009 (replaces No. 1768/92). Such a certificate can extend the term of a patent on the medicinal product by up to 5 years.

Duty to complete the admission procedure

In the various legal systems there are different provisions on which medicinal products are subject to the obligation of the authorization procedure. In the European Union under Article 2 is Directive 2001/83 / EC , the European pharmaceutical law applicable to such medicines in the Member States placed on the market should be and are either prepared industrially or an industrial process is used in their preparation for application . The German pharmaceutical law determines the authorization requirement for finished medicinal products , the Austrian law uses the term medicinal specialty analogously. This is to be understood as meaning drugs that have been manufactured in advance and are given under the same name in a pack intended for dispensing to the consumer or user. In Switzerland, the authorization requirement applies to ready-to-use medicinal products.

This is generally based on a comprehensive pharmaceutical term , which also includes vaccines , many blood products and in vivo diagnostics . However, there are problems with product delimitation in individual cases .

Medicines that are subject to authorization make up the overwhelming majority of medicinal products in use today. However, there are a number of exceptions that still do not fall under the authorization requirement. In the European Union, homeopathic medicinal products and traditional herbal medicinal products can be placed on the market according to a simplified approval process (called “registration” in Germany), provided they meet the relevant, legally regulated requirements. In this simplified procedure, only the quality and safety must be proven; In the case of registered homeopathic medicinal products, no indication may be given; in the case of traditionally used herbal medicinal products, reference must be made to the traditional use in the indication formulation. Similarly, Switzerland provides for a simplified authorization procedure for complementary medicine. Prescription and defensive drugs manufactured in pharmacies, as well as investigational drugs for clinical studies, are not subject to authorization . Under certain conditions, drugs that have not (yet) been approved can be made available to patients as part of compassionate use .

harmonization

Since 1990, within the framework of the International Council for Harmonization (ICH), essential drug testing guidelines for the verification of quality, safety and effectiveness as well as document formats for the approval documents have been harmonized. The ICH is supported by authorities and industry representatives from Europe, the USA and Japan. The aim of the harmonization was that non-clinical and clinical studies from one region are recognized in the other regions, so that they do not have to be carried out more than once. However, the individual authorities are independent in their assessment of the approval applications, so it happens again and again that certain drugs are not approved in all regions.

Admission criteria

The most important approval criterion is the weighing of the risk-benefit ratio ; Authorization is only justified if the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks. If the benefit-risk ratio of the drug becomes unfavorable after approval has been granted, the drug must be withdrawn from the market. A drug approval is only ever granted for a specific area of application, a specific indication . The use of an approved drug outside of the approved indication is called off-label use .

Examination of the approval documents

The main focus of the approval process is the review of the documents submitted by the pharmaceutical company, which are intended to prove the quality, effectiveness and harmlessness. The drug authority also checks whether it has been proven in the various phases of the drug study that the production, quality control, non-clinical testing and clinical testing (phase III) were carried out in accordance with the prescribed drug testing guidelines and the recommended international guidelines and that they correspond to the state of the art . However, the drug authority does not limit itself to examining the documents submitted by the applicant, but rather uses on-site inspections to check whether the studies have been carried out in accordance with the rules of good working practice (GxP).

Required approval documents

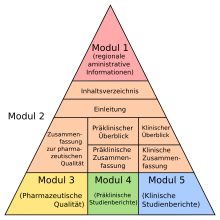

The pharmaceutical company must submit a comprehensive dossier on the drug in a defined format, the Common Technical Document Format (CTD), with the application for approval. The CTD dossier contains all the results for the manufacture, research and development of the drug in question in five modules . In detail, the dossier in CTD Module 1 contains regionally specific information and in CTD Module 2 an overview and summaries of the following modules. CTD module 3 contains a quality part that describes how the drug can be manufactured in sufficient pharmaceutical quality and how this is analyzed and detected, CTD module 4 the prescribed non-clinical pharmacological and toxicological studies; CTD Module 5 includes all data from the clinical studies .

The CTD format was developed in the ICH. The aim when the CTD was introduced was that largely identical dossiers could be submitted in different regions. The format is now mandatory in Europe, North America and Japan. Many applicants now submit their dossiers electronically in the form of an eCTD .

In order to continuously demonstrate drug safety, pharmaceutical companies must meet numerous legal requirements, including: a. A competent person must be appointed, there must be a risk management plan and the availability of responsible officers must be ensured at all times.

Pharmaceutical grade

The pharmaceutical quality of a drug is the composition of the drug according to the type and amount of its components. The German Medicines Act defines quality as the nature of a medicinal product, which is determined by identity, content, purity, other chemical, physical, biological properties or by the manufacturing process.

For approval it is necessary that the drug is of an appropriate quality in accordance with recognized pharmaceutical rules. These rules are laid down in pharmacopoeia monographs , among other things . The documents to be submitted are not limited to the composition of the medicinal product. The entire manufacturing process and the controls of the raw materials, intermediate products and finished products as well as shelf life studies are to be documented in detail.

Before a drug is approved, the manufacturer must obtain a manufacturing license. The production must be carried out according to the rules of Good Manufacturing Practice ; this is inspected by the authorities on site. If necessary, samples of the drug can be tested for pharmaceutical quality in official drug testing centers.

effectiveness

The effectiveness of a drug is the sum of the desired effects in the intended area of application. The desired effects can be a cure, amelioration, or prevention of the disease. Appropriate efficacy of the drug in the intended indication is required for approval. This is not to be understood as a guarantee of success for every patient, but a probability that therapeutic or preventive results can be achieved with the drug. There are several acceptable methods for determining efficacy, which differ in their level of evidence . If possible, randomized controlled trials on clinical endpoints such as morbidity, hospitalization and mortality should be conducted. However, there are reasons recognized by the approval bodies for the fact that the effectiveness of the study design and / or the recorded parameters is only made probable with little evidence, for example through epidemiological comparisons or the recording of surrogate markers . According to a ruling by the German Federal Administrative Court, the term therapeutic effectiveness means the "causality of the use of the drug for the healing success." The studies must have been carried out according to the rules of Good Clinical Practice ; the authorities check this through on-site inspections.

One of the problems of the proof of effectiveness is that it is often carried out in studies on groups of patients who do not match the patients in everyday clinical practice, for example in terms of age, gender distribution and severity of the disease. In individual cases, the question of the everyday relevance of the proof of effectiveness arises.

Harmlessness

Under the aspect of harmlessness, the possible harmfulness of a drug is primarily assessed. The term harmlessness has long been in use in German pharmaceutical law; Internationally one speaks mostly of security. According to the German Medicines Act, medicinal products are questionable if, according to the current state of scientific knowledge, there is a justified suspicion that, when used as intended, they have harmful effects that go beyond what is justifiable according to the knowledge of medical science.

There is no absolute measure of what side effects are acceptable; the questionability can only be assessed in consideration of the severity of the disease to be treated. When assessing the harmlessness of a drug, its effectiveness should also be taken into account. Harmlessness does not mean harmlessness. The pharmacologist Gustav Kuschinsky wrote that drugs that are claimed to have no side effects are suspected of not having a main effect.

The safety of the drug must be demonstrated in non-clinical and clinical studies . The non-clinical trial contains a comprehensive toxicity determination that must be carried out in suitable in vitro and animal experiments . In clinical trials , all side effects and serious adverse events in the participants are carefully documented and evaluated.

The problem is that the side effects in clinical studies can only be documented in a comparatively small number of patients; In principle, rare and very rare side effects cannot be identified. The same applies to long-term effects due to the limited duration of the studies. This means that at the time of approval it can only be a preliminary assessment. A complete safety profile can only be obtained with widespread use and careful application monitoring by pharmacovigilance .

Risk-benefit ratio

The risk-benefit ratio of a drug is the relationship between the effectiveness of the treatment on the one hand and all possible risks related to the quality, safety or effectiveness of the drug on the other. This ratio is of central importance for the decision on the approval of the drug. The term benefit-risk ratio goes further than the term “harmlessness”, since not only the risks for the patient, but also for public health and the environment must be taken into account.

There is no generally accepted standard for this relationship; this always requires an individual decision. As with safety, the assessment of the risk-benefit ratio at the time of approval can only be provisional. The inadequate generalizability of the benefit-risk ratio derived from the approval studies was demonstrated for example for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs .

For this reason, the risk-benefit ratio should be continuously checked in pharmacovigilance after approval; if the relationship becomes unfavorable, the remedy must be withdrawn from the market. Although the concept of the benefit-risk ratio has been in use in drug evaluation for many years, it was only introduced into various articles of the EC directives and regulations in 2004 with the reform of EU pharmaceutical law.

Proof of an efficacy superior to the risks is sufficient for approval under the drug law; superiority over other drugs is not required. Recently, further assessment procedures for the benefit assessment or the cost-benefit assessment of drugs have been introduced in many countries, for example in Germany by the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) or in the United Kingdom by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . These assessment procedures are not part of the drug approval. They are used to assess the reimbursement of drugs by health insurance companies .

Summary of Product Characteristics

In the course of the approval process, the essential information on the medicinal product, which has been substantiated by study results and which the applicant and the approval authority agreed in the wording, is summarized in the summary of product characteristics . This important document contains all the essential information such as indication, contraindication , dosage , interactions and side effects including the evaluation and weighing up. This summary can only be changed after approval with the approval of the authority.

Admission process

Approval procedures are regulated by national regulations and international agreements. In addition, the medical background on which approval is based is continuously being further developed through developments from consensus-based medicine to evidence-based medicine .

European Union

In the course of the implementation of the European internal market , standardized procedures for EU approval were introduced in 1995, so that different bureaucratic hurdles no longer have to be overcome in every EU country. For this purpose, the legal framework was harmonized across the EU with Directive 2001/83 / EC for the creation of a community code for human medicinal products and Directive 2001/82 / EC for the creation of a community code for veterinary medicinal products. Various EU approval procedures have been developed, some of which are based on the coordination of decentralized institutions and some on centralization. In any case, however, the national authorities continue to perform key functions.

Centralized procedure

The main procedure for innovative medicines is the centralized procedure based on Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 . This procedure is mandatory for a number of medicinal products. These include drugs for advanced therapies and monoclonal antibodies, as well as human drugs with new active ingredients for the treatment of AIDS , diabetes mellitus , cancer , neurodegenerative diseases , autoimmune diseases and other immune deficiencies and viral diseases . Also orphan drugs to treat rare diseases and veterinary drugs to improve performance fall necessarily under the procedure. Access to this procedure is optional for a number of other medicinal products.

In the centralized procedure, the scientific assessment and the approval decision are institutionally separated. The application for approval must be submitted to the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The assessment procedure for the application for authorization is carried out by the scientific committees - in the case of medicinal products for human use, the Committee on Medicinal Products for Human Use - of the European Medicines Agency; High-ranking representatives of the national pharmaceutical authorities are sent to these committees by the member states. A rapporteur selected from the responsible scientific committee of the Agency and a co-rapporteur, together with experts from the national medicines authorities, prepare an assessment report for the medicinal product, which is adopted by the responsible scientific committee of the European Medicines Agency no later than 210 days. On the basis of this opinion, the European Commission grants approval for the entire European Union within 67 days after consulting the member states in the Standing Committee . National and European institutions therefore work closely together in the centralized procedure. The granted EU approval is regularly adopted in the European Economic Area (EEA).

The consumer can see whether a medicinal product has been centrally authorized by means of the authorization number; the number then begins with the identifier "EU". For example, one of the approval numbers for Humira is EU / 1/03/256/007 . The second digit indicates whether it is a veterinary or human medicinal product (1 = human, 2 = veterinary). The third digit indicates the year of the first approval, here 2003.

Between 1995 and September 2007 around 400 medicinal products for human use and 75 medicinal products for veterinary use were authorized in the centralized procedure. A detailed European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) is published for every newly authorized medicinal product .

Decentralized procedures (MRP and DCP)

With the mutual recognition procedure (MRP) and the similar decentralized procedure (DCP), an application for approval is examined by the authority of a member state (reference member state) and an assessment report is drawn up. The authorities of the other Member States concerned then recognize this assessment in a coordinated process. The applicant can choose for which member states of the EU and EEA he wants to apply for authorization.

In the mutual recognition procedure, a national authorization is first applied for and granted in a country of choice, before identical applications are then submitted in the other countries and the recognition procedure is started. In the decentralized procedure introduced in 2005, there must be no national approval in the EU; Here, identical applications are submitted simultaneously in all states and one state is selected as the reference member state.

If individual member states reject the assessment of the reference member state because of a serious risk to public health, all participating states must endeavor in a coordination group to reach an agreement on the measures to be taken. If the authorities in the coordination group cannot come to an agreement, arbitration proceedings will ensue in the scientific committee of the European Medicines Agency. On the basis of the assessment by the Scientific Committee, the European Commission makes a final decision in the arbitration procedure after consulting the Member States in the Standing Committee.

In the non-centralized procedures, approval is always granted by the national authorities.

Several hundred non-centralized procedures are carried out each year; a large number of these are generics .

National procedures

Until 1995, national procedures were the only way to approve a medicine in the EU. These national procedures have lost much of their importance due to the European procedures. However, there are many drugs on the market that have been approved using such procedures. Today, purely national approval is only possible in one member state; national applications for approval in more than one member country are no longer permitted. Today, such a national approval is usually the starting point for the mutual recognition procedure. In Germany, the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) for "normal" drugs, the Paul Ehrlich Institute for blood products and vaccines , the Friedrich Loeffler Institute for immunological veterinary drugs against exotic animal diseases and the Federal Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety for veterinary drugs responsible. In Austria pharmaceuticals are by the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety area Medicine Market Authority (formerly AGES PharmMed) approved and monitored.

Switzerland

Since Switzerland is neither a member of the European Union nor the European Economic Area, Switzerland carries out all drug approvals autonomously; In principle, however, approvals from countries with comparable drug controls can be taken into account. The legal basis is the Therapeutic Products Act , which regulates medicinal products as well as medical devices. Details on approval can be found in the drug approval ordinance. The body responsible for approval and drug monitoring is Swissmedic . The internal processing time for authorization applications is 200 days, for applications in the accelerated procedure 130 days. There is a simplified approval procedure for certain medicinal products, including those with known active ingredients, medicinal products from complementary medicine, hospital preparations and medicinal products for rare or life-threatening diseases.

United States

In the USA, drug approval is a process that starts much earlier than in Europe.

In principle, the process in the USA begins with the application for approval of the first clinical study (Investigational New Drug application, IND) . There, not only abstracts, but full study reports are submitted, unlike the approval process for clinical trials in Europe, which can then be added continuously in a rolling submission in the course of clinical development (rolling submission) . In this case , many documents have already been assessed for the actual approval application, the New Drug Application , NDA . Once the NDA has been accepted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as complete and in accordance with the formal requirements, the application will be reviewed by the FDA within a set period. After hearing a committee of experts and the pharmaceutical company, the FDA decides whether the drug will be approved, whether the application is approvable , which means that the FDA agrees to approve the drug under certain conditions to be met by the applicant, or whether the Application is rejected (not approvable) .

Only 10% of all drug developments that begin human clinical trials receive FDA approval.

According to the Animal Efficacy Rule, proof of effectiveness in animal experiments is sufficient under certain conditions .

International recognition of approval decisions

Even if many criteria for drug approval have been harmonized in many countries and the pharmaceutical companies often submit practically identical documents, the authorities come to contradicting decisions in individual cases. This is due to the fact that the authorities have a great deal of leeway when it comes to approval and that essential statements about the drug are based on probability statements.

In the European Union, it took three decades for national authorities to develop sufficient mutual understanding to enable the EU approval process to be successful.

The European authorities on the one hand and the FDA on the other are a long way from this point. For example, a drug containing rimonabant was approved in the European Union in 2006 , while the FDA rejected an application for approval for the same drug in 2007 due to safety concerns. Conversely, the cancer drug Mylotarg with the monoclonal antibody gemtuzumab-ozogamicin was approved in the USA as early as 2000, while the application for approval in the EU was rejected in 2008.

Accordingly, various efforts to mutually recognize drug approvals internationally have so far only led to partial success. Mutual Recognition Agreements for the mutual recognition of inspections on Good Manufacturing Practice have been concluded between the European Union, Australia, Japan, Canada, New Zealand, Switzerland and the USA. The agreement with the USA has not yet been implemented, the one with Japan only partially.

Special procedures and categories

Special routes for faster access

Drug development and approval are a lengthy, multi-year process. In order not to unnecessarily delay access to innovative, possibly life-saving drugs, special procedures have been introduced in the European Union and the USA that are intended to accelerate approval in exceptional cases.

The accelerated assessment procedures ( accelerated assessment ) of the EU centralized procedure and the priority review process at the FDA have significantly reduced processing times compared to the regular procedure. This can accelerate approval by several months; In the EU, the processing time in the scientific committee is reduced from 210 to 150 days. The authorities check on a case-by-case basis whether an application is processed in this procedure. In the USA up to 2006 alone, around 10 to 15 drugs were processed and approved in the priority review each year ; in the EU, eculizumab was the first drug approved in the accelerated process in the summer of 2007.

The conditional approval ( conditional marketing authorization ) of the EU centralized procedure on the basis of Regulation 507/2006 / EC allows the individual case, particularly in life-threatening diseases to bring a drug before completing the full clinical trial on the market. In this case, the pharmaceutical company undertakes to meet the conditions specified by the authority within a certain period of time, for example to provide complete phase III data; the conditional approval is valid for one year, but can be extended annually after assessment by the authority until a regular approval is granted. This procedure is only possible after a case-by-case examination. The first drug with conditional approval in the EU was Sutent (active ingredient: Sunitinib ) in summer 2006 . According to a study, for medicinal products with conditional approval in the EU in the period from 2006 to 2015, the average time to fulfill the requirements was four years, with more than a third of the procedures in this context being delayed or inconsistent. The authors conclude that the conditional approval enables access to drugs whose clinical value has not been fully established over a longer period of time, with possible corresponding risks for the patients.

The accelerated approval in the USA has similarities with the conditional approval in the EU; Here, too, provisional approval is granted, with the condition that clinical studies be carried out and concluded in which a patient benefit is proven with clinically relevant endpoints. The accelerated approval is mainly based on surrogate markers for the decision . The problem is that companies in the USA often fail to meet the requirements of completing clinical studies after approval.

The approval in exceptional cases ( under exceptional circumstances ) in the EU centralized procedure comes into question when probably no complete data can be made about the efficacy and safety are available for a drug in the future, perhaps because their detection is not unethical possible or or disease to be treated is very rare. The conditions are reassessed annually.

With PRIME ( priority medicines ), the EMA has been offering drug manufacturers a procedure since 2016 that can always be chosen when there is a lack of supply in an area (“ unmet medical need” ) , i.e. when there is an effective therapy is missing or the new agent offers a therapeutic advantage. In particular, small companies or university institutions should be supported through continuous regulatory and scientific advice in the very early development phases. Over 60 drugs have been included in the PRIME program so far (as of 2020).

The concept of Adaptive Pathways (German for "adaptable ways"; also referred to as Medicines Adaptive Pathways to Patients , MAPP) is part of the EMA's efforts to give patients faster access to new drugs through more flexibility within the existing legal framework. The adaptive pathway concept is based on three principles: First, iterative development - this means either gradual approval, starting with a limited patient population that can be expanded to a larger population, or the confirmation of a balanced risk-benefit ratio Conditional approval product based on early data with surrogate markers studied as predictors of key clinical outcomes; second, on the collection of evidence on health care data (“real life use”) in order to supplement the data from clinical studies; third, the early involvement of patients and review panels in the discussion about drug development. The BfArM and the EMA tested the adaptive pathway approach from 2014 to 2016 in a pilot project. Critics fear lowering of approval standards at the expense of the previously strictly regulated approval aspects of effectiveness and harmlessness. The adaptive pathways should initially only be used for certain drugs, for example if there is an urgent need due to a lack of treatment alternatives ( unmet medical need ). Follow- up on the project includes working with health technology assessment bodies and additional stakeholders such as patients and payers.

Emergency procedures

A “ rolling review ” is one of the regulatory tools available to the EMA in centralized approval processes to expedite the evaluation of a promising investigational drug during a public health emergency such as a pandemic. Rapporteurs are already being appointed while development is ongoing and the EMA will keep the data under review as it becomes available.

For influenza vaccines (flu vaccines) for use in pandemic situations there are also special procedures in order to accelerate their availability. In the EU, this includes the “model vaccine procedure” ( mock-up procedure ), with which an already approved model vaccine is adapted to the current pandemic virus strain as soon as it is identified, and the “ emergency procedure ”, which enables rapid Approval of a new influenza vaccine that is being developed following a pandemic report made possible. For both procedures, the normal procedure duration is reduced from 210 to 70 days. A third procedure is for the approval of vaccines that have already been approved for use against seasonal influenza, but have been modified in such a way that they can be used to protect against pandemic flu. This procedure is usually practiced nationally, as most seasonal flu vaccines are also nationally approved.

In the USA, there is the option of issuing an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for pharmaceuticals . Emergency Use Authorization for "medical countermeasures" ( Medical countermeasures , MCMs) may be issued by the FDA when the existence of an emergency has been detected in the field of public health, for example in the event of a CBRN -Bedrohung or pandemic. The legal basis is the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act).

Orphan drugs

Orphan drugs are drugs that are used to treat, prevent, or diagnose a rare disease . Rare diseases in this sense affect less than 5 in 10,000 people in the EU. In the EU, orphan medicinal products must be authorized in a centralized procedure; Orphan Medicinal Status is awarded by the European Commission based on a recommendation by the Committee for Orphan Medicines (COMP) of the European Medicines Agency. This was done for 500 drugs by September 2007; 36 of these have been approved so far. For orphan drugs, pharmaceutical companies receive support from the European Medicines Agency in planning the necessary studies, as well as discounts on approval and inspection fees and ten-year market exclusivity.

Generics

Generics are essentially identical drugs that contain the same drug in the same dose and dosage form as a reference drug that is no longer patented. Simplified authorization conditions apply to these medicinal products. For this purpose, the manufacture and pharmaceutical quality must be documented and the bioavailability and bioequivalence to the original medicinal product must be documented. For the rest of the non-clinical and clinical data, the applicant can refer to the data on the reference medicinal product. In the EU, however, regardless of patent protection, this is only possible eight years after the approval of the reference drug, the approval itself is only granted ten years after the initial approval has been granted. For biosimilars special conditions apply.

For drugs with already known active ingredients, there is another application type with simplified approval conditions beyond the "general medical use" ( well-established use ): The applicant does not have to submit data from his own preclinical and clinical trials if he can prove that the active ingredients of the drug have been used for general medical purposes in the EU for at least ten years. Other relevant scientific documentation, from which the already known effects and side effects can be seen, then replaces own studies. For example, for medicinal products with known herbal active ingredients, the monographs drawn up by the Committee for Herbal Medicinal Products can be used.

Procedure after approval has been granted

Granting a license is a crucial step, but that by no means ends the regulatory activities. The registration documents must be continuously updated and the use of a medicinal product must be constantly monitored. In the case of new drugs, approval is only granted for a limited period of time, usually five years. Before this period expires, the approval must be renewed, usually it is then unlimited. However, if an approved medicinal product is not placed on the market within a specified period, or if it is not on the market for a longer period of time, approval usually expires ( "sunset clause" ). For EU countries this deadline or period is three years.

Change notifications

The pharmaceutical company has an obligation to notify the competent authorities of all changes that affect the granted authorization. Depending on the extent to which the changes are to be carried, some of them have to be approved by the authorities. Simple changes that only need to be notified are, for example, administrative changes at the manufacturer or minor changes in the manufacturing process. Changes to the dose , the dosage form or the application form , for example, require approval . Any change to the summary of product characteristics also requires approval.

If the approval of a drug is to be extended to a further indication, this requires a separate, complete application for approval.

Pharmacovigilance

The pharmaceutical company is obliged to collect and evaluate findings on adverse drug effects even after approval has been granted. The supervisory authority must be reported on this at specified intervals, and in the case of severe, unexpected cases of side effects, also within short periods of time. Continuous monitoring is important because in clinical trials with only a few thousand patients, it is not possible to detect rare or very rare side effects. Side effects that occur very late are also difficult to record in the approval studies.

New findings can lead to the restriction of the approval, for example by changing the summary of product characteristics. If, during the use of a drug, there is evidence of serious side effects that make the risk-benefit ratio unfavorable, approval can also be completely revoked. Of the drugs with new active ingredients approved in the USA between 1975 and 1999, 2.9% were withdrawn from the market due to deficiencies. In the United Kingdom it was 3.8% between 1972 and 1994. The predominant reason for the withdrawal from the market are unacceptable side effects. In some cases, such as clobutinol , the approval was only withdrawn due to safety concerns after the drug had been used for decades.

In the area of pharmacovigilance, too, the pharmaceutical authorities conduct inspections at pharmaceutical companies to check whether the prescribed monitoring measures are being implemented correctly.

History of drug approval

Approval procedures have been introduced worldwide after the pharmaceutical preparation has been largely replaced in pharmacies by industrial production and various drug scandals had shaken confidence in the safety of medicines.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the industrial production of pharmaceuticals had largely supplanted pharmacy preparation. However, few countries had marketing authorization procedures for pharmaceuticals as early as the first half of the twentieth century, including France, Sweden, Norway and especially the USA. In the USA, the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938 made approval of new drugs mandatory; this law was passed by Congress after the sulfanilamide disaster . However, the approval criteria were then limited to pharmaceutical quality and safety; At that time, a drug was considered approved if the competent authority, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), did not object within a certain period of time.

The effectiveness criterion and the current approval procedure were only introduced in the USA in 1962 by the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendment , which was discussed at the same time as the thalidomide scandal was uncovered . The events at that time had a lasting impact on the legislative process; The original legislative process in Congress against excessive drug prices and unfair drug advertising became a consumer protection law. The restrictive admission criteria developed in the USA at that time were adopted by many other countries in the following years. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, accelerated approval procedures were introduced in the United States in response to the urgent need for drugs to treat AIDS .

Also as a consequence of the thalidomide scandal was in the European Economic Community , the Directive / / EEC 65 65 of the Council of 26 January 1965 on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to medicinal products approved. For the first time, this provided for a license to place drugs on the market and required proof of therapeutic efficacy. The following Directive 75/319 / EEC of 1975 was much more detailed in the approval requirements. In addition, a new European expert panel was created by Directive established the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (Engl. Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products, CPMP ), a forerunner of today's Committee for Human Use (CHMP). In 1987, Directive 87/22 / EEC defined the consultation procedure for innovative medicinal products, a forerunner of today's centralized procedure, which was defined in 1993 with Directive 2309/93 / EEC and implemented from 1995 onwards. It was not until the reforms that came into force in 1995 that the Community procedures were widely used. In the review of the European pharmaceutical legislation from 2001 to 2004, the current framework was created.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, the implementation of the first EEC directive from 1965 into national law was a lengthy process, which only came to an end with the entry into force of the second Drugs Act of 1976 . It was not until 1975 that an institute for drugs for drug approval was founded in what was then the Federal Health Office ; after the Federal Health Office was dissolved in 1994 as a result of the blood-AIDS scandal, it became today's Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices . The application of the new legal instruments to old pharmaceuticals in the reauthorisation procedure lasted until the end of 2005 in Germany.

literature

- Martin Lorenz: The common drug approval law with special consideration of the reform 2004/2005. Nomos-Verlags-Gesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2006, ISBN 3-8329-1912-0 .

Web links

- EudraLex - Volume 2 - Pharmaceutical legislation on notice to applicants and regulatory guidelines for medicinal products for human use

- European Medicines Agency

- Federal Institute for Pharmaceuticals and Medical Products

- Paul Ehrlich Institute

- Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety

- Swissmedic (Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Elizabeth Storz: Drug Safety. In: GIT Labor-Fachzeitschrift. August 2008, pp. 712-714.

- ↑ Section 4 (15) AMG.

- ^ Karl Feiden , Hermann Pabel: Dictionary of Pharmacy. Volume 3: Drugs and Pharmacy Law. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8047-0670-3 .

- ↑ Directive 2001/83 / EC , Annex I, Part I, Section 5.2.5.1.

- ^ Robert Kemp and Vinay Prasad: Surrogate endpoints in oncology: when are they acceptable for regulatory and clinical decisions, and are they currently overused? , BMC Medicine Volume 15, Article 134 (2017), accessed October 30, 2019

- ↑ STIKO: Methods for the implementation and consideration of modeling for the prediction of epidemiological and health economic effects of vaccinations for the Standing Vaccination Commission , March 16, 2016, accessed October 30, 2019

- ↑ FDA: Table of Surrogate Endpoints That Were the Basis of Drug Approval or Licensure , online September 30, 2019, accessed October 30, 2019

- ↑ BVerwG E Volume 84, pp. 215–224, judgment of October 14, 1993 Az. 3 C 21.91.

- ↑ § 5 AMG.

- ↑ Dieter Hart: The benefit / risk assessment in pharmaceutical law. An element of the Health Technology Assessment. In: Federal Health Gazette . Volume 48, 204-14 (2005), PMID 15726462 . doi : 10.1007 / s00103-004-0977-2

- ^ P. Dieppe, C. Bartlett, P. Davey, L. Doyal, S. Ebrahim: Balancing benefits and harms: the example of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In: BMJ . Volume 329 (7456), 2004, pp. 31-34, PMID 15231619 .

- ↑ Scientific Advisory Board of the Paul Ehrlich Institute: Minutes of the constituent meeting on May 30, 2017 ( PDF )

- ↑ Centralized procedure on the website of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices, accessed on June 10, 2020.

- ↑ Volume 2A - Procedures for Marketing Authorization, Chapter 2 - Mutual Recognition. ( PDF ) In: EudraLex - Volume 2 - Pharmaceutical legislation on notice to applicants and regulatory guidelines for medicinal products for human use .

- ↑ Statistics on non-centralized approval procedures at the Heads of Medicines Agencies .

- ↑ Information for pharmaceutical companies , on the FDA website.

- ↑ Opinion | The Solution to Drug Prices . ( nytimes.com [accessed October 29, 2018]).

- ↑ International Cooperation in Pharmaceuticals - Key documents , EU Commission. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ↑ Accelerated assessment in the EMA glossary, accessed on June 10, 2020.

- ↑ NME Drug and New Biologic Approvals in 2006 , FDA Document Archive, accessed June 10, 2020.

- ↑ New Molecular Entity (NME) Drug and New Biologic Approvals , FDA website, accessed June 10, 2020.

- ↑ EMEA concludes first accelerated assessment for a medicine for human use , EMA press release of April 27, 2007 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Conditional marketing authorization in the EMA glossary, accessed on June 10, 2020.

- ^ R. Banzi, C. Gerardi, V. Bertele, S. Garattini: Approvals of drugs with uncertain benefit-risk profiles in Europe . In: European Journal of Internal Medicine . tape 26 (2015) , pp. 572-584 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ejim.2015.08.008 .

- ^ CD Furberg, AA Levin, PA Gross, RS Shapiro, BL Strom: The FDA and drug safety: a proposal for sweeping changes. In: Arch Intern Med . Volume 166 (18), 2006, pp. 1938-1942, PMID 17030825 .

- ↑ Exceptional circumstances in the EMA Glossary, accessed June 10, 2020.

- ^ European Medicines Agency : PRIME: priority medicines. Retrieved June 12, 2020 .

- ↑ a b EMA: Adaptive pathways : 'The adaptive pathways approach is part of the European Medicines Agency's (EMA) efforts to improve timely access for patients to new medicines', accessed on September 10, 2017.

- ↑ Final report on the adaptive pathways pilot summary of the pilot project from July 28, 2016, accessed on September 10, 2017.

- ^ PV Bonanno et al .: Adaptive Pathways: Possible Next Steps for Payers in Preparation for Their Potential Implementation . In: Frontiers in Pharmacology . tape 8 (2017) , doi : 10.3389 / fphar.2017.00497 , PMC 5572364 (free full text).

- ↑ HG Eichler et al .: Medicines Adaptive Pathways to Patients: Why, When, and How to Engage? In: Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics . tape 105 (2018) , no. 5 , doi : 10.1002 / cpt.1121 , PMC 6585618 (free full text).

- ^ European Medicines Agency: How EMA fast-tracks development support and approval of medicines and vaccines. Retrieved June 12, 2020 .

- ↑ a b European Medicines Agency (EMA): Authorization Procedures. Retrieved June 12, 2020 .

- ^ FDA: Emergency Use Authorization. Retrieved June 27, 2020 .

- ↑ European Medicines Agency for Orphan Medicines ( Medicines for rare diseases. ) ( Memento from January 31, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) (English).

- ↑ Well-established use in the EMA Glossary, accessed June 10, 2020.

- ↑ Directive 2001/83 / EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to human medicinal mid l , Article 24th

- ↑ Regulation (EC) No. 726/2004 , Article 14.

- ↑ KE Lasser, PD Allen, SJ Woolhandler, DU Himmelstein, SM Wolfe, DH Bor: Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. In: JAMA . Volume 287 (17), 2002, pp. 2215-2220, PMID 11980521 .

- ^ DB Jefferys, D. Leakey, JA Lewis, S. Payne, MD Rawlins: New active substances authorized in the United Kingdom between 1972 and 1994. In: Br J Clin Pharmacol . Volume 45 (2), 1998, pp. 151-156, PMID 9491828 .

- ↑ Jürgen Feick: Market access regulation: National regulation, European integration and international harmonization in drug approval. In: Roland Czada, Susanne Lütz (Hrsg.): The political constitution of markets. Westdeutscher Verlag, Wiesbaden 2000, ISBN 3-531-13415-9 , pp. 228–249.

- ^ Jürgen Feick: Marketing authorization for pharmaceuticals in the European Union. In: Joining-up Europe's Regulators. European Policy Forum, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-903850-29-9 , pp. 35-63.

- ↑ Reinhard Kurth: The development of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) in the face of increasing European competition. In: Federal Health Gazette. Volume 51 (3), 2008, pp. 340-344, PMID 18369569 .