Phylakopi

Phylakopi ( Greek Φυλακωπή ( f. Sg. )) Is a Bronze Age settlement on the Greek Cycladic island of Milos in the Aegean Sea . From its initial phase at the end of the early Cycladic period there are innovative forms of ceramics. In the Middle Cycladic and Late Cycladic / Mycenaean times it was next to Agia Irini on the island of Kea the largest known city in the region.

Research history

The settlement was excavated from 1896 to 1899 by archaeologists from the British School at Athens under the direction of David George Hogarth , Arthur Evans and Duncan Mackenzie . The finds were documented in an exemplary manner and are now in the National Museum in Athens . In 1911 a small excavation was carried out to confirm the sequence of layers from three urban epochs, but this was not evaluated until 1974. In the same year new excavations began under the direction of Colin Renfrew , which lasted until 1977. The excavations of the 1970s brought a reassessment of the settlement structure in the Middle Cycladic period.

A detailed publication of the excavations of the 1970s was only made in 2007 by Renfrew. In it he rejected large parts of the previous dates and proposed a new sequence of buildings. According to this, the urban character of phylacopies would not set in until around 200 years later and instead of three he suggested four characteristic phases. This interpretation met with criticism, in particular it was objected that Mackenzie and the excavators at the end of the 19th century had far too good knowledge of the construction forms and ceramic styles to make such extensive errors in the dating. More recent analyzes, with reference to the unpublished excavation reports by Mackenzie, show that the original dates, at least when separating the second from the third epoch, cannot be kept.

Early settlement structures

The earliest traces of settlement are graves, which, according to the design and grave goods of the Grotta Pelos culture, were between 3000 and 2650 BC. ( For chronological classification see: Cycladic culture ). Some wall remnants that are not yet addressed as parts of a city are assigned to the same era. At that time Phylakopi was just a village settlement. The island's dry layered limestone masonry was between 30 and 60 cm thick. Mortar was not used. Because of the overbuilding in later phases, only a few foundation walls can be found, a connection between the rooms can no longer be established.

Phylakopi in early Cycladic times

The oldest urban buildings in Phylakopi date from the end of the early Cycladic period. The first were assigned by Mackenzie to the end of the early Cycladic epoch II, Renfrew wants to assign them to the village structures. The main part is from the years shortly before 2000 BC. They gave their name to the Phylakopi culture , with which the demonstrable history of the Cyclades after a break in settlement continuity at the end of the Kastri culture around 2200 BC. Is resumed.

The ceramics of this era show a multitude of new elements: for the first time, a mineral coating can be found on the vessels made of red, brown or black clay , which has a matt sheen. Patterns are often scratched into this coating and filled with a white mass so that the patterns stand out clearly. Some vessel shapes are also new. In addition to the still widespread conical pots, so-called duck vases are now appearing , spherical vessels with a beak-shaped spout with a wide spout. For the first time, these vessels have only one handle that connects the spout with the top of the abdomen. Also new are the jugs with a towering spout, a spout that is pointed at one end and a handle from the back of the spout down to the body. These vessels are often painted with a white coating. Pithoi , storage vessels with a deep, largest diameter and large opening are another innovation. At the end of the early Cycladic period, their size ranged from 25–30 cm for the small, up to 70 cm for the large. In later epochs they will be built into the building floors with the same basic shape up to a man's height and firmly.

In general, much more elaborate vessels are found in Phylakopi than in earlier epochs and other settlements of the Cycladic culture. The inhabitants of the city lived in a relative prosperity and used artistically shaped and painted ceramics. The climax is reached with the so-called kernoi : donation vessels that are composed of several small bowls, often mounted on a foot and decorated with different, mostly geometric patterns. The bowls of oil lamps , which are also mounted in pairs or in threes on a common holder, are similar .

Two finds of erect animal figures holding a bowl in front of their breasts appear curious. They are interpreted as badgers or hedgehogs.

Middle Cycladic Period (2000 BC-1600 BC)

Only three settlements from the Central Cycladic period have been excavated: Besides Phylakopi, Agia Irini on Kea and Phourion on Paros . However, a total of 20 settlement locations are known, a significant increase compared to the 15 of the previous epoch.

The first urban settlement was found in Phylakopi. The British excavators at the end of the 19th century assigned their finds to a Cyclopean defensive wall, ornate frescoes and houses with large rooms whose ceilings were supported by pillars. Even if these attributions had to be revised in the 1970s and these findings were assigned to all later strata at the beginning of the late Cycladic or Mycenaean culture , there are still enough differences to previous cultures for Phylakopi to detect a change of epoch.

The city was densely built up and covered an area of around 220 m in length and no longer determinable in width, because parts of the rock plateau slipped into the sea. It had a regular structure of streets about six feet wide, just enough for two donkeys to avoid each other. The walls were on average 0.60 m thick. For the first time, clay mortar is used almost entirely to connect the basalt and limestone masonry . After the great wall was assigned to later eras, there is no longer any evidence of a fortification, nor does the street grid indicate a central sanctuary or palace. But the city must have had a busy port, as finds have been made in the buildings that indicate intense trade. Ceramic factories in Phylakopi produced goods that were found from Crete to Argolis in the Peloponnese in the entire southern Aegean and on the adjacent mainland. On the other hand vessels were found in the city, by the Attic originate mainland and the minyischen be assigned Style, and occasionally those of Crete in the Minoan style .

All of the obsidian of the Middle Cycladic period came from the island of Milos and was processed in Phylakopi. The glass was the material for most of the tools of the Bronze Age, it was beaten into narrow blades and retouched into scrapers and arrowheads . The obsidian trade is considered to be the basis of the city's prosperity.

Mycenaean time

In the late Cycladic period from 1600 BC The cultures of the Aegean Islands merged with those of the mainland. While the influence of the Minoan culture can still be observed at the beginning of the epoch, especially on the Cycladic island of Santorin and the city of Akrotiri , which is closest to Crete , the other Cycladic islands, including Milos, can increasingly be assigned to the Mycenaean culture of the Attic mainland. In Phylakopi an increase of the previously very low Minoan influence can be observed before it is replaced by the Mycenaean culture much more quickly and further. The transition between the buildings of the Central Cycladic and Mycenaean epochs is controversial. Mackenzie's assignment of several important buildings to the Middle Cycladic period is contradicted by Renfrew. He dates the portico of the manor house and major parts of the city wall to the early Mycenaean era. The evaluation of Mackenzie's excavation documents supports this assumption. Brodie states that Mackenzie assigned walls found in the second stratum to both its second, Middle Cycladic, and third, Mycenaean, epochs. This can be explained by the use of earlier foundations and the methodology of the excavation technique at the end of the 19th century. In later excavations Mackenzies as assistant to Arthur Evans in Knossos in Crete, he was able to gain further experience.

The early Mycenaean city

At the transition from the Middle Cycladic to Mycenaean times, the city was almost completely redesigned. Although the basic pattern, block sizes and street width were adopted, the old foundations were only occasionally used again. Whether it was destroyed by war or fire, or whether a coordinated action by the residents reacted to signs of decay, can no longer be determined. It may also be a gradual transformation within about a generation, which today looks like a general rebuilding thanks to tight planning.

Some of the houses were two-story, others had basement rooms that were completely or partially underground. Four walls with doors have been preserved. The door frames were made of wooden beams or stone slabs. They were so low that a grown man would have to bend down safely. For the first time, rooms are so large that the ceiling has to be supported with a central pillar.

Some rooms were painted with frescoes. In addition to the most famous mural of flying fish, fragments of two other motifs have been preserved. They show a seascape and two seated men. One of the two is wearing a golden bracelet and is holding a cloth in his hand, the regular folds of which reveal Cretan influences.

The most extensive structures were a building known as a mansion and the fortification wall that characterizes the image of the excavation site today.

The mansion has an unusual size for the Bronze Age of 5.70 m × 13.60 m. The main room, which can be seen as a megaron , was preceded by a small anteroom. Further details can no longer be determined. Due to its location in one of the few squares in the city, it is identified as the seat of the commercial administration. Clay tablets with texts in the Cretan Linear A script were found in the rubble of the building .

Only the south-west corner and around 100 m of the south side of the city wall have been preserved. The wall is a maximum of 4 m high and an average of 2 m thick, made of large and carefully hewn blocks. Gaps are filled with small stones. It does not have a continuous exterior, but consists of individual sections that spring back and forth, which increases stability and makes it easier to fight enemies. There are no gates in the preserved part.

The pottery of this time is characterized by the adoption of Minoan motifs, which are produced in large numbers and with only a few variations.

Late Mycenaean extensions

Around the year 1400 BC The city was largely rebuilt within a short time. Again, the old grid was basically used, but this time only a few foundations were used. While Mackenzie viewed the Mycenaean period as a single entity, Renfrew interpreted the late Mycenaean phase as an independent, fourth epoch. Mackenzie already recorded corresponding assumptions in his excavation report, but did not include them in the publication. The settlement is less well preserved than its predecessor.

Its importance lies primarily in three new buildings and the cult figures found there.

- The already huge city wall was reinforced. The old, 2 m thick wall was juxtaposed with a second wall of the same thickness at a distance of 2 m. With irregular transverse walls, the construction was divided into individual chambers, most of which were filled with earth. But some could also have been used as rooms, perhaps guard rooms. A city gate has been preserved from this period.

- A Mycenaean palace was built on the bottom of the older mansion, shifted by almost two meters compared to the old foundations. It consisted of the main wing with a vestibule and the main room of 8 m × 6 m, as well as a corridor to an escape of side rooms, which could have been women's apartments. The water supply to the palace through a 9 m deep well is striking.

- The peak of the excavations in the 1970s was the discovery of a complex interpreted as a sanctuary. In the south of the city, leaning against the defensive wall, two foundation units were excavated. The so-called western sanctuary consists of a large room measuring 6 m × 6.60 m with an entrance in the east wall, to which two small side rooms adjoin in the west. In the main room there were two stone tables interpreted as altars . It was made around 1360 BC. Built in BC. The building called the Eastern Shrine was added later. It adjoins at a right angle to the northeast and has its entrance from the side of the courtyard, which forms with the western sanctuary and the city wall. Beginning of the 12th century BC The system was destroyed and only poorly repaired.

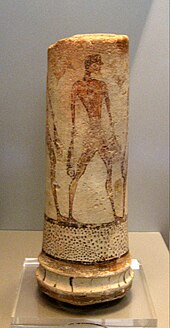

Various figures and statuettes were found in the rubble of the two sanctuaries. They allow an insight into the religious ideas of the time, even if the interpretations have to remain speculative.

The most spectacular is the so-called Lady of Phylakopi , a clay figure 45 cm high, which shows a presumably female figure whose arms, which have not been preserved , were raised in adoration . In addition, a large number of male statuettes have been preserved. Two of them represent a club-wielding deity, as it is known from the Middle East . Seven bull figures were found in the same context, two of which are designed as vessels with spouts. In addition, a large number of smaller figures and shapes and ten seal stones.

The city of Phylakopi was founded around the year 1100 BC. Abandoned BC. The destruction of the building complex, interpreted as a sanctuary, is estimated to have been around 1120 BC. The cause is believed to be an earthquake that also severely damaged Agia Irini on Kea. But since in the 12th century BC BC all urban settlements on the neighboring islands are given up, and on Paros , for example, destruction by humans has been proven, a collapse of the entire culture must be assumed. The eastern shrine was still used for a short time, then there are no more evidence of settlement from Phylakopi.

On the Greek mainland, however, already around or shortly after 1200 BC Massive upheavals took place in the 3rd century BC: the Mycenaean palace centers were destroyed, many settlements abandoned, and some regions, such as Messinia , even almost depopulated. The Mycenaean palace economic system collapsed and with it the use of writing was probably lost. Although the Mycenaean culture continued to exist for at least 150 years and in the more populated places (including Tiryns and Mycenae) there were at times certain after-blooms of the Mycenaean culture, but the events on the mainland around 1200 were so decisive that the so-called Mycenaean palace period ended and in Greece after 1200 BC BC, no later than 1050/30 BC BC, with the end of the Mycenaean culture, the so-called " Dark Centuries " begin. It was even more drastic around 1200 BC. Large parts of Central Asia Minor in particular , where a Dark Age dawned for more than four centuries after the collapse of the Hittite Empire (approx. 1190/80 BC) . Why Phylakopi and with it large parts of the Aegean island world from the massive upheavals and destruction from 1200 BC. BC apparently largely spared, has not yet been conclusively clarified.

literature

- Werner Ekschmitt : The Cyclades. Bronze Age, Geometric and Archaic Age . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1533-3 .

- Jack L. Davis: Minoan Crete and the Aegean Islands . In: Cynthia W. Shelmerdine (ed.): The Cambridge companion to the Aegean Bronze Age , Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 9780521814447

Web links

- Dartmouth College: Aegean Prehistoric Archeology on the prehistory of the Cyclades

- Foundation of the Hellenic World website : Lady of Phylakopi

Individual evidence

- ↑ Colin Renfrew: Excavations at Phylakopi in Melos 1974 - 77 (= The British School at Athens, Supplementary Volume 42, 2007), ISBN 978-0-904887-54-9 .

- ^ Todd Whitelaw: A tale of three cities - chronology and minoanization at Phylakopi in Melos. In: A. Dakouri-Hild; S. Sherratt (Ed.): Autochthon - Papers presented to OTK Dickinson on the Occasion of his Retirement. Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-1841718682

- ↑ a b c d Neil Brodie: A Reassessment of Mackenzie's Second and Third Cities at Phylakopi. In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . Volume 104, 2009, ISSN 0068-2454 .

- ↑ a b c Jack L. Davis: Minoan Crete and the Aegean Islands . In: Cynthia W. Shelmerdine (ed.): The Cambridge companion to the Aegean Bronze Age , Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 9780521814447 , page 197

- Jump up ↑ Dartmouth College: Aegean Prehistoric Archeology - Post-Palatial Twilight: The Aegean in the Twelfth Century BC (English)

Coordinates: 36 ° 45 ′ 17.9 ″ N , 24 ° 30 ′ 16.5 ″ E