Pluteus (lectern)

As Pluteus (Latin, plural plutei ), also: plutei grammaticales that is lectern referred that in the libraries of the monasteries and the first public reading rooms since the late Middle Ages , both the storage and the use of the collected manuscripts and early printed books allowed. The term has lost its meaning since the 18th century due to the changed requirements for a public library and has been largely forgotten.

origin

The Roman poet Aulus Persius Flaccus (34–62 AD ) used the term pluteus (German protection wall , board ) to describe a lectern in one of his satires. The plural plutei for the library stalls goes back to a mention of the Gallic aristocrat Sidonius Apollinaris in the 5th century. In his letters, Sidonius describes the establishment of the library in a prefect's villa . He names the shelves - in distinction to cupboards ( armaria ) and boxes (cunei ) - as grammaticales plutei .

Writing and reading space

The plural plutei , used in the Middle Ages, took into account that the reading places in the monastery libraries were single seats with a desk, which corresponded to the work places in the scriptoria and made it possible to store the writings, books and writing materials needed for reading as well as copying.

The font collections in the monasteries of the early Middle Ages were still comparatively small. The St. Gallen monastery plan , a floor plan from the 9th century, shows a system of individual places ( sedes scribentium ) on the two sides of the room exposed from the outside with a bookcase ( bibliotheca ) in the rather square extension to the central church Center. It was not until the 14th century that larger rooms with benches and desks ( pulpitum , repositorium ) for the storage and use of scriptures were found in the monasteries, especially for the monasteries of the mendicant orders , primarily the Franciscans and Dominicans , who had extensive book collections. Evidence of the desk libraries in the Gothic monasteries is often only available in written sources, such as in the Augustinian library directory in Kulmbach , or by means of the painting of rooms by comparing and deriving the image motifs , such as for the auditorium in the Cistercian monastery Maulbronn (c 1440/50).

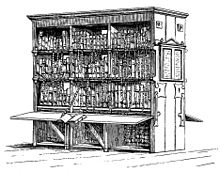

In woodcuts from the late Middle Ages and the 15th to early 16th centuries, the reading areas are shown as wooden, ornate compositions of a seat and a desk that houses the books. The shape of the desk shelves and their rows to form benches, with which the monasteries of the 14th century set up chapel-like rooms for their books and writings, inspired the design of the first public libraries in the Renaissance .

Reading bench

Arranged in rows, the still common pews are reminiscent of the lecterns in libraries of the early modern era . The books, secured by chains , were often stacked under the desks . The list of books relevant for the respective row found its place on the side of the stalls. The librarian placed the books on the desk at the user's request; the chain prevented them from being laid, but also prevented the theft and damage to the weighty specimens, artfully bound in leather over wood , through carelessness, because they could not fall off this way. The reader had to wander if he wanted to consult different volumes.

In addition to the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence, there are still fully preserved reading rooms with benches and desks from the 15th and 16th centuries in De Librije in Zutphen ( Netherlands ) and in the Biblioteca Malatestiana in Cesena ( Italy ). In the Laurenziana in Florence, the signatures of the approximately 3,000 bound manuscripts collected there still have their former storage location in the plutei stalls: this is how the Codices Laurentiani are listed with the abbreviation MS Plut (eus) .

Bookcase with desk

In the later versions of the reading desks in the libraries, the readers sat back to back on benches in front of unfolded desks between the bookcases. The height-building arrangement of the books had become necessary due to the constant expansion of the library holdings. Compared to the reading benches of the early libraries with their pieces stored horizontally, the user had a larger selection of volumes at their disposal. The book directories were on the side walls of the bookcases, the books stood with the front cut facing outwards and were still chained.

The library of the cathedral in Hereford ( England ) has to the rack systems one with their built in the early 17th century bookcases a step on the way from the first public reading benches Magazining preserved vividly. Also in England are other preserved bookshelf libraries from the 17th century with lecterns in Wimborne Minster and in the Trigge Library in Grantham (Lincolnshire) .

Reorganizations

The latter two examples from the 17th century herald the space-saving arrangement of books and their use , which is common in private libraries : the books on the wall, the reading and work space free in the room. The library building of the 18th century preferred a free display of the books without chains and without permanently installed reading areas in rooms specially designed for this purpose, as was realized in the establishment of the Duchess Anna Amalia Library in Weimar in 1766. The beginning of the mass production of books from around 1840 onwards increased the public library holdings rapidly and in the 19th century required both a modern set of rules for the registration and the still usual separation of the magazine and open access area . Associated with this was the renovation and new construction of the libraries. The plutei grammaticales had become unnecessary and the old, first public reading chairs were forgotten along with their term.

literature

- Steffen Diefenbach, Gernot Michael Müller (ed.): Gaul in late antiquity and early Middle Ages. Cultural history of a region . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2013; P. 405

- Winfried Nerdinger (Ed.): Wisdom builds a house. Architecture and History of Libraries . Exhibition catalog Munich July 14 - October 16, 2011. Prestel, Munich / London / New York 2011 ( table of contents , abstract )

Web links

- Reading in Restraint: The Last Chained Libraries at: atlas obscura , accessed December 30, 2014

Individual evidence

- ↑ Persius Satires 1, 106 [1] .

- ↑ Sidon. epistol. 2, 9, 5; see also Diefenbach / Müller (2013) p. 405 (with Latin text and its translation).

- ^ A b c Heinfried Wischermann: "Claustrum sine armario quasi castrum sine armamentario". Comments on the history of the monastery library and its research. In: Nerdinger (2011, pp. 93–130); a) p. 100, b) p. 102-105, c) p. 106.

- ↑ De Librije, de unieke kettingbibliotheek in de Walburgiskerk te Zutphen (from: De Librije een unieke bibliotheek , accessed on December 30, 2014).

- ↑ Biblioteca Malatestiana (accessed February 13, 2016).

- ^ Historical photography on Flickr .

- ^ Ulrich Naumann: University Libraries . In: Nerdinger (2011, pp. 131–148); P. 132.

- ^ Hereford Cathedral: The Chained Library ( February 14, 2013 memento in the Internet Archive ) (accessed December 30, 2014).

- ^ Jenny Weston: The Last of the Great Chained Libraries , 2013. (From: medievalfragments , accessed December 30, 2014) .

- ^ Wimborne Minster: Chained Library (accessed December 30, 2014); historical photo .

- ^ The Trigge Library (at: St. Wulfram's.org.uk , accessed December 30, 2014).

- ↑ An older illustration of the library's spiral staircase illustrates the conceptual absence of integrated reading areas.

- ↑ Peter Vodosek : Knowledge for all: From the public enlightenment to the public library until today. In: Nerdinger (2011, pp. 195-214); Pp. 203-205, pp. 210-211.