Polonia (national allegory)

Polonia is the Latinized form of the name of Poland and the female symbol of the country. As an identity- creating figure, she was used especially during times of crisis. As a personified allegory, it is closely linked to the religious conception of the Virgin Mary .

Emergence

The symbolic representation of a country as a woman has a long tradition and probably has first evidence in the statues of Pallas Athene . In Roman antiquity, the attributes of the patron saint of Athens were transferred to Roman equivalents. These are the goddesses Minerva , as one of the three highest deities in a spiritual sense, and Roma , as the embodiment of the city of Rome or the Roman state.

This division of responsibility for the otherworldly and thisworldly world is found again later in the 17th century in the equally close connection between the Mother of God, Mary, and Polonia.

In the song of praise "Gaude Mater, Polonia" (Latin for joy, mother Poland ) from the 13th century, Polonia is addressed as a person for the first time. The text of the hymn goes back to a rhyming breviary that was written by Vincent von Kielcza (Polish Wincenty z Kielczy , approx. 1200 - after 1262). Melodically, it is based on Thomas Aquinas' Gregorian chant “O Salutaris Hostia”, which today is better known as a student song under the name Gaudeamus igitur .

After the first lecture during the celebrations for the canonization of the Polish national saint Stanislaus of Krakow (or of Szczepanów; Polish Stanisław ze Szczepanowa ), the song became more and more popular and was even elevated to the royal hymn among the Piasts , although the text had primacy places religious authority above royal power. The frontispiece from Stanisław Orzechowski's work "Quincunx Polonia" from 1564 shows the special relationship between fatherland, ecclesiastical and secular power. The hymn accompanies Polish tradition and history and is still used today as a patriotic song at many universities at the opening of the academic year and at major national holidays.

In the first half of the 17th century, especially after the Council of Trent , there was a steadily growing devotion to Mary. This development was openly promoted by the Italian Jesuits from 1656 onwards and in many European countries it led to Mary being declared the national patroness.

As a result of the victorious defense of the Jasna Góra monastery in Czestochowa against the Swedish troops (the victory was interpreted as a miracle of the Black Madonna in view of the overwhelming power of the attackers ), the Polish King John II Casimir declared Our Lady Regina in 1656 in the Lviv Cathedral Polonia (Queen of the Polish Crown). The meaning of the secular and clerical figures of identification overlapped, similar to what was already the case with Roma and Minerva in the Roman Empire .

A recurring image of Polonia shows it as Antemurale Christianitatis (bulwark of Christianity; Latin “antemurale” for “front wall”). This title, which became part of the national self-image, was acquired by the Polish Catholics in their defensive struggles against Russian Orthodoxy and Islam .

In 1607 Jan Jurkowski published the epic "Chorągiew Wandalinowa" (translated The Flag of Wandalin ). It contains a wood engraving showing the hero with a flag. It shows Polonia threatened by her opponents: a Swede with a trident, a Muscovite with a battle ax, a Tatar archer and finally a Turkish gunner .

Artistic reception

In addition to music, the idea of a “mother Poland” was also adopted by other areas of art, which was mainly used during the times of the partition of Poland between 1772 and 1914. In 1830, Poland's national poet Adam Mickiewicz took up the idea of the mother country again in his lamentation poem “Do matki Polki” (translated To the Polish mother ). It was in direct contrast to the "Gaude Mater, Polonia". There it says: "Gaude, mater Polonia, / prole fecunda nobili" (Latin Rejoice, mother Poland / fertile in noble descendants ), but in this text the son of the Polish mother awaits prison, forced labor and death on the gallows. The former hymn of praise is transformed into a melancholy elegy , which, however, with Mary's motherhood establishes a connection to the Polish mother and is intended to provide consolation and confidence.

The pessimistic view found its expression in the painting of the Polish Romanticism . After the failed uprising in January 1863 , the painter Jan Matejko chose a humiliated and shackled Polonia as a symbol of the loss of statehood and the oppression of the Polish nation by the occupying powers Russia , Austria and Prussia .

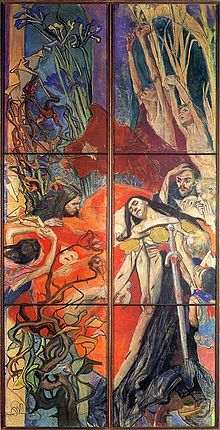

From then on, the allegory of Poland was consistently presented in contexts of death, violence, humiliation and imprisonment. Another important work in this context is the dead Polonia by Stanisław Wyspiański , which was created as a stained glass window for the Lviv Cathedral between 1892 and 1894. Like hardly any other work of art, it has become a folk icon in the collective memory of the Poles, not least because it has found mass distribution in the form of postcards. As a token of her royal dignity, the dead woman wears a purple coat with ermine trimmings. Next to her lies the sword " Szczerbiec " (in Polish roughly "jagged sword"), which was used in the coronation ceremonies of the Polish kings. She is surrounded by a group of grieving people, including women in typical Polish costumes. Despair, paralysis and weakness are reflected on their faces and in their gestures. The depiction of all these emotions makes it easy for the viewer to identify with Polonia.

The expectation of salvation that was linked to that of the “Dead Polonia” can be seen in several works by Włodzimierz Tetmajer , a student of Matejko. On his mural in the Wawel Cathedral , Polonia is laid out in front of Our Lady. The corpse here is also equipped with royal attributes such as clothing, the burial crown of Casimir the Great and the orb. A white lettering under the stretcher with the words “non mortua sed dormit” (Latin not dead but sleeping ) maintains the hope that Poland is not yet lost.

It wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that the method of representation slowly changed again and the artist Jacek Malczewski even painted an ironic picture in his famous portrait of Aleksander Wielopolski . The work called Hamlet polski. Portret Aleksandra Wielopolskiego shows the leader of Congress Poland with Polonia in a double role. On his left she stands as an old, careworn old woman in handcuffs, on the other hand the painter depicts a young, buxom, slightly frivolous woman with broken chains on his right.

A complete break with the tradition of representation in the context of deprivation of rights provides to the French national symbol Marianne reminiscent Polonia artist Zdzislaw Jasinski . In his allegory titled "Warszawo naprzód" (translated forward Warsaw ) he makes them strong and determined defenders propel the city to victory in the Battle of Warsaw (1920) .

Further representations

literature

- Bahlcke, Rohdewald, Wünsch (ed.): "Religious places of remembrance in East Central Europe" . De Gruyter, 2013, ISBN 978-3-05-009343-7 ( google.de ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Anna Rothkoegel, "The Mothers of Nations - Images, Myths, Rituals" (PDF 1.4 MB)

- ↑ Text of the hymn "Gaude Mater, Polonia" (Latin, Polish)

- ↑ Melanie Obraz, depictions of Mary before and after the Council of Trento ( Memento of the original from August 2, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF 2.3 MB)

- ↑ a b Katharina Ute man, Polonia, a Nationalallegorie as a memorial in Polish painting of the 19th century