Combed rodent beetle

| Combed rodent beetle | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Combed rodent beetle, comb-horned beetle ♂ |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Ptilinus pectinicornis | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

|

|

Antennae males antennae females  |

| Fig. 1: Top view ♂ | Fig. 2: Bottom ♂ | |

|

|

|

| Fig. 3: Front view ♂ | Fig. 4: Side view ♂ |

Fig. 5: Drawings 1836 |

The Combed furniture beetle ( Ptilinus pectinicornis ), also comb horn beetle and outdated Langstrahliger comb Horn borer , spring horn beetle or books drill called, is a beetle from the family of the furniture beetle . The genus Ptilinus is represented in Europe with five species . The beetle is classified as a wood pest and is not protected. The biology of the important dry wood destroyer is largely known. In addition to the antennae of the males, the polymorphism of the larva is unusual.

Notes on the name

The species, which is conspicuous because of the antennae of the males, is well known. It was already described by Linnaeus in 1758 under the name Dermestes pectinicornis in the famous 10th edition of his Systema Naturae , which is considered the starting point of the binomial nomenclature . The description consists of the few words D. fuscus, antennis luteis pennatis ( Latin: a dark dermestes , with yellow combed antennae) and a location. This explains the generic name pectinicornis (from Latin "pécten" for "comb" and "córnu" for "horn, feeler"). This is also reflected in the combed parts of the name and Kammhorn - the German names. Such antennae can only be found in a pronounced form in males, but also in males of other species of beetles.

The genus name Ptilinus first appeared in a book on the insects in the Paris area in 1762. As can be seen from the second edition of the book in 1764, the author of the book was Geoffroy . Geoffroy listed the beetle with the French binomial "Panache brune" (brown plume) as the first of the two species he counted in the genus Ptilinus . He was referring to the fourth species that Linnaeus has under Dermestes , namely Dermestes pectinicornis , and also adopted Linnaeus' Latin description of the beetle given above. However, he did not give the species a scientific name in accordance with the nomenclature rules . He avoided binomial nomenclature in the rest of the book as well. There was therefore a difference of opinion as to whether Geoffroy's designations were valid or not. The issue was regulated by the ICZN in Opinion 228 in 1954 in such a way that the names used by Geoffroy in his book could not be taken into account when determining nomenclature. In 1764 OF Müller cited the generic names from Geoffroy, in contrast to those used by Linnaeus, without specifying the species. In 1776 Müller gave an identification key for the genus Ptilinus , named Ptilinus cylindricus as the associated species and continued to refer to Geoffroy. Because of this, Müller was now considered the author of the genre in 1776 and one can find in the literature the information " Ptilinus Müller", " Ptilinus OF Müller" and " Ptilinus Geoffroy in Müller" with different dates. The rigid interpretation of the nomenclature rules in Opinion 228 , however, was objected to, and in 1994 the ICZN in Opinion 1754 recognized some of the names for beetle genera by Geoffroy, so he is now also considered the author of the genus Ptilinus . Geoffroy explains the name: The Panache was so named because of the shape of its antennae, which form a kind of feather head; this is exactly what the Latin name Ptilinus means (fr. La panache a ainsi nommée à cause de la forme des ses antennes, qui representent une espèce de panache: c'est aussi ce que signifie le nom latin Ptilinus ). The name Ptilinus is from ancient Gr. πτίλον "ptílon" derived for "down feather".

Characteristics of the beetle

The cylindrical body is more than twice as long as it is wide and therefore more elongated than that of Ptilinus fuscus , which also occurs in Central Europe . The beetle becomes 3.5 to 5.5 millimeters long, the females are on average larger than the male. The species is black-brown, the wing-coverts lighter brown, antennae and legs rust-red. The beetle looks frosted due to its very short and fine yellow or gray hairs.

The head is bent under in the resting position and placed against the chest (Fig. 4). The chest does not show any recesses to accommodate the head or the antennae. The round eyes are moderately large and arched, larger in the male than in the female. The eleven-link antennae are inserted at the lower edge of the eyes. They look significantly different in males and females (Fig. 3). In both, the large and curved base member is thickened forward. The second antenna element is small and protruding inwards in a triangular manner. In the male, the triangular third limb is drawn out into a short lamella inside, the following limbs have a very long, somewhat flattened process inward, which is longer than the head and pronotum combined and gives the antennae its feather-like appearance. In females, the antennae are deeply serrated. In the male, a more or less distinct, slightly downwardly curved transverse furrow runs between the forehead and the vertex.

The upper jaws are short triangular and hairy on the outside. The jaw probes are four-membered with a long, approximately cylindrical end member. The three-part lip stylus has a small base link, the long middle link is cylindrical, the slightly shorter end link is slightly thickened in the middle and slightly truncated at the end.

The pronotum is strongly rounded and strongly arched in front and on the sides. It does not close tightly to the wing covers . It is wrinkled with a fine grain, the grain becomes clearer towards the front. A smooth elongated bump can be seen in front of the label. In the female, a very flat, smooth bump is formed on both sides of the rear half of the pronotum.

The light elytra are rounded together at the back. In the middle area, their sides run parallel to each other. The elytra have flat, irregular rows of dots .

The underside of the beetle (Fig. 2) is characterized by a long metasternum and five abdomen sections of roughly the same length. The front and middle hips are closer to each other, the rear hips less. The front splints have a tooth pointing horizontally outwards at the tip. The five-membered tarsi are rather slender and little expanded towards the tip. The first tarsal link is long, the second shorter, and the following three much shorter.

egg

|

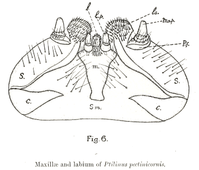

Fig. 6: Larva, underside of the head according to Barbey s. Stipes, c. Cardo, la. Lacinia, mx.p. Jaw button, l. Lower lip lp lip probe, m. Chin (Mentum), sm. Submentum |

|

|

| Fig. 7: Drilling holes in oak | |

The egg is very soft-skinned and malleable. It is already very elongated in the ovaries. It is stretched again during the laying process. It is then around twenty times as long as it is thick.

larva

The first larval stages are not very similar in Ptilinus pecticornis . The first larval stage has roughly the thread-like shape of the egg and ends with a tooth plate, a holding and movement organ. In the second stage there is no tooth plate, the front part of the larva is rounded, the end of the abdomen is still thread-shaped. The third larval stage is initially club-shaped, but the end of the body is increasingly pushed into the cavity created by the gnawing activity. These larval forms are determined by the space available in the wood. Only the fourth larval stage strongly resembles the blind, squat larvae of the rodent beetle (see picture on web links). Fully developed legs are only present in the 5th and 6th larval stage.

When fully grown, the larva becomes about five millimeters long with a diameter of three millimeters. It is white with a yellowish head, which is sunk into the first breast segment. It is curved and fleshy. The three chest sections merge steplessly into the ten sections of the abdomen, the diameter of which decreases steadily towards the rear. The last abdominal segment is sack-like. The three pairs of legs on the chest are very short. Small hooks on the side of the eighth and ninth body segment support locomotion. There are transverse ridges on the back. The whole body is finely haired. The first breast segment and the first eight abdomen segments each have a breathing opening ( stigma ) on the lower side , whereby the stigma of the front chest is slightly larger than the abdominal stigma. Viewed from above, the head is divided into three large areas, which are separated from one another by seams: the triangular forehead and, on both sides behind it, two halves of the epicranium . The tiny antennae are each in a pit on the front corners of the forehead. The front of the forehead is clearly curved inward. The epistome lies in front of the forehead as a narrow strip , the naked clypeus in front of its center as a broad square , in front of it the upper lip in the form of a segment of a circle. The front and sides of the upper lip are covered with strong, short bristles. These also form two lines on the top of the upper lip. The strong upper jaws are dark brown. Compared with the upper jaws of other wood-eating beetle larvae, they form a transition from the toothed forms that bite off pieces of wood and the forms with a cutting edge that resembles a chisel, which scrapes the wood very finely and thereby unlocks the wood cells: At the lower edge of the cutting surface are two rudimentary ones Teeth present. The underside of the head is illustrated in Fig. 6. The lower jaw consists of stipes (s.), Cardo (c.), Lacinia (la.) And jaw palpation (mx.p.). In Ptilinus the Lacinia (la) is particularly strongly rounded. The chin (m.) Is narrow and elongated.

biology

nutrition

The larva and the finished beetle feed on wood. The digestion of the wood takes place with the help of endosymbionts , which are related to yeast . These are given by the mother animal during oviposition with the ovipositor of the eggs ( engl. Egg-smearing). The larvae become infected when they eat part of the eggshells when they hatch. The endosymbionts live in specialized, multinucleated large cells, the mycetocytes. These form the majority of the epithelium of protuberances at the front end of the midgut, the mycetomas. In Ptilinus pectinicornis, the mycetomas are connected to the intestinal lumen by thin channels. During the transformation to the imago , only a small part of the symbionts is absorbed into the slimmer mycetome of the imago.

Drill holes

In old forest books you can find the information that the boreholes run in all directions . This impression can also arise on superficial examination (Fig. 7). It was specified early on, however, that the larval ducts are mainly driven in the direction of the wood fibers, whereas the adult burrows run perpendicular to the surface into or out of the wood.

After hatching from the eggs, the larva prefers to dig in the direction of the wood fibers, even through completely healthy wood. If the infestation is dense, this creates many closely spaced, parallel tunnels. To open up new wood areas, so-called alternating corridors are created, which run diagonally. The doll's cradle runs approximately in the direction of the fibers. The larval feeding tunnels are very densely filled with drilling dust. This is clumped in floury and consists of faeces and grated wood.

The debris from the finished beetle contains more fine chips. The adult animals largely use existing passages. If you want to leave the wood after hatching, drill your way out perpendicular to the grain. The loopholes are circular with a diameter of two to 2.5 millimeters. Even with a new infestation, the females penetrate the wood perpendicular to the grain. With this they create a breeding tunnel. Usually, however, the breeding tunnel is created from existing tunnels, often from the pupal's own cradle, also perpendicular to the grain.

Life cycle

The beetles hatch in late spring, the males a few days before the females. The beetles are short-lived, the males die soon after mating, the females soon after they lay eggs. The hatched beetles spend most or all of their lives in the feeding tunnels in the wood. In order to copulate, however, the locally loyal animals usually have to leave the wood, as the bore holes are too narrow for mating. For this purpose, the animals find themselves near the loopholes on the wooden surface in the evening hours.

The unfertilized females show an unusual lure posture, which is known as sterling . With the head lowered, the hind legs are lifted up and the abdomen is straightened at an angle. A gland that appears moist becomes visible in the folded-up anal segment. After about twenty seconds, this posture is briefly replaced by a normal posture, and then the posture is resumed. Experiments have shown that a sex hormone is released that acts as an attractant for the males. These aim at the source of the fragrance with lively feeler movements and approach it. An approach with the legs was triggered up to a distance of one meter. It is estimated that a flying male will also be attracted from a significantly greater distance. According to the current state of knowledge, it must be doubted whether there is also acoustic communication, as with other rodent beetles, in which the beetles knock their heads on the walls of the feeding ducts.

Mating takes place outdoors. Observations in nature show that when mating, one copulation partner is occasionally inside the passage near the exit, while the second is only connected by the copulation organs in the open. However, this can be explained by the fact that the female tries to get to safety after copulation has taken place. The pairing takes place in different stages. The male sitting on top of the female triggers the female's play dead reflex by waving the head and antennae of the female. In this state, the penis is inserted without the female being able to see it. The male then turns 180 degrees so that both animals sit one behind the other, hanging from each other, abdomen to abdomen, heads turned away. One or both copulation partners can withdraw into a borehole. The copula is terminated after five to fifteen minutes with the male turning back to the female.

When laying eggs, a distinction is made between primary and secondary attacks. If the development conditions are good, the females stay on or in the infested wood and use existing drill holes. If necessary, they clear out the drill dust or, starting from a pupa cradle, create a short breeding tunnel across the grain, in which they lay the eggs (secondary infestation). If the wood is infected with Anobium punctatum at the same time , its tunnels are also used. If, on the other hand, a new breeding site is sought, the females drill short breeding tunnels into the wood perpendicular to the fibers and lay the eggs there (primary infestation). As a starting point for these passages, they prefer to choose areas where the bark has been removed due to injuries. Otherwise, bumps in the bark are used as the starting point for the breeding process. The time it takes to drill in depends on the hardness of the wood and is two to three days. The drilling continues during the day, while the other activities take place in the evening and at night.

The eggs are not laid directly in the lumen of the breeding tunnels, but in the mainly large-lumen wood cells cut vertically through the breeding tunnels. The originally elongated eggs are stretched considerably when they pass through the laying tube when they are introduced several millimeters into the vascular cells. Eggs laid in poplar wood are 1.5 millimeters long with a transverse diameter of 0.075 millimeters. They are inserted half a millimeter to one millimeter deeper than the length of the egg.

The first larval stage has roughly the thread-like shape of the egg. The head is turned towards the brood. With the help of the tooth plate at the end of the abdomen, the larva moves away from the breeding duct within the vascular cell by up to a few centimeters. After gnawing through the cell wall, the larva sheds its skin. The second stage lacks the tooth plate, the front part of the larva fills the space created by the feeding activity, the thickness of the abdomen is limited by the thickness of the wood cell. The third larval stage is initially club-shaped, but the thinner end of the body is increasingly pushed into the cavity created by the feeding activity. Only from the 4th larval instar is the larva curved and the abdomen turned under. Fully developed legs are only present in the 5th and 6th larval stage.

In the case of both primary and secondary infestation, the females remain in the brood path after they have laid eggs until they die. In this way, they close the breeding channels with their bodies to the outside and protect eggs and newly hatched larvae from predators. Approximately twenty offspring can be expected per female. Nevertheless, given favorable conditions, there can be local mass occurrences over several years.

The trunks of beech are primarily attacked . Also oak and numerous other hardwoods are attacked, including a few softwoods, while the other Central European Art Ptilinus fuscus developed only in softwoods. The infestation of conifers is also reported again and again. In breeding experiments, breeding tunnels are also created in coniferous wood, but no oviposition has yet been observed. So far, no eggs have been detected in breeding programs in conifers outdoors.

When grown under suitable conditions (70% humidity, addition of starch, room temperature), the development takes about a year. It usually lasts two years under natural conditions, and several years under unfavorable conditions.

Natural enemies

Among the insects will

- the colored beetle Tillus elongatus is known as a predator that preyes on the larvae. Be considered a parasite

- the wasp Eusandalum inerme

- the wasp Calosota vernalis

- the brackish wasp Spathius exarator

- a parasitic wasp of the genus Hemiteles is mentioned.

Harmfulness

Since the beetles also attack trees with minor injuries that would otherwise have healed and at least weaken them and reduce the quality of the wood, they must be classified as harmful from the perspective of conventional forestry. Infested trees must be removed, otherwise they will attract more wood pests. In an old encyclopedia the beetle is listed as a pest on the sweet chestnut .

From another point of view, the beetle is one of the species that promote the natural decomposition of deadwood. In a large-scale standardized procedure in two largely natural forests in Italy with medium-sized beetle branches that had fallen to the ground and which were still largely barked, the beetle was clearly the most common of all beetle species grown from these branches.

While the beetle can play an important role in the decomposition of wood under natural conditions, its share in the destruction of built-in or processed wood is rather small compared to other rodent beetles. In the above-mentioned investigation of fallen beetle branches, the most common beetles were by far Ptilinus pectinicornis , while in two statistical investigations of cultural goods damaged by rodent beetles, in one case only 15% and in the other only 6% of the infected objects were damaged by the combed rodent beetle. In individual cases , the damage caused by Ptilinus pectinicornis to half-timbering, wooden floors, wooden objects improperly stored in monasteries or museums such as furniture, utensils, picture frames, iconostases and the like can be considerable. It is reported from Romania that there are wooden churches in which the ceiling of the nave is made of beech wood and which, at least with the help of Ptilinus pectinicornis, are partially damaged to such an extent that they break under slight mechanical pressure.

The name book drill has been passed down. However, the beetle or its larvae do not pierce books, but occasionally wooden book covers. This can still pose a current threat to valuable old books.

distribution

The beetle is of Eurasian origin, but was found in New York in 1950 and is now considered a cosmopolitan. It is widespread in Europe, mainly in Central and Central Europe where it is of economic interest. In Central Europe it does not occur in alpine regions. It is also absent in the northern regions of Scandinavia. On the Spanish peninsula, however, its occurrence is limited to the northern areas. In addition, the distribution area extends to Asia Minor and Siberia. Contrary to the information in Fauna Europaea, the beetle can also be found in northern Portugal.

literature

- Heinz joy , Karl Wilhelm Harde , Gustav Adolf Lohse (ed.): The beetles of Central Europe . tape 8 . Teredilia Heteromera Lamellicornia . Elsevier, Spektrum, Akademischer Verlag, Munich 1969, ISBN 3-8274-0682-X . P. 49

- Edmund Reitter : Fauna Germanica, the beetles of the German Empire III. Volume, KGLutz 'Verlag, Stuttgart 1911 p. 315, plate 122/6

- Wolfgang Willner: Pocket dictionary of the beetles of Central Europe . 1st edition. Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelsheim 2013, ISBN 978-3-494-01451-7 . P. 26

- Klaus Koch : The Beetles of Central Europe Ecology . 1st edition. tape 2 . Goecke & Evers, Krefeld 1989, ISBN 3-87263-040-7 . P. 275

Individual evidence

- ↑ J. David Labram, Ludwig Imhoff: Insecten der Schweiz Basel 1836-1845; Illustration of the feeler

- ^ Ptilinus pectinicornis in Fauna Europaea. Retrieved April 7, 2015 and genus Ptilinus from Fauna Europaea. Retrieved April 7, 2015

- ↑ Carolus Linnaeus: Systema Naturae .... 1st volume, 10th edition, Stockholm 1758 p. 359: 355

- ↑ Sigmund Schenkling: Explanation of the scientific beetle names (species)

- ↑ a b Geoffroy (the author is only mentioned in the 2nd edition 1764): Histoire abregée des insectes que se trouvent environ de Paris 1st volume Paris 1762 p. 98:64

- ↑ E. Bergroth: Remarks on the Catalogus Coleopterorum Europae in Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift, 1907 for keeping the names Geoffroy p. 575

- ^ Gv Seidlitz: Is Geoffroy to be regarded as a valid author? in German Entomological Journal, 1908, pp. 359f

- ↑ J. Weise Are Geoffroys generic names permissible p. 91 and Geoffroy Again p. 150 Wiener Entomologische Zeitung Vol. 2 1883

- ^ Edward T. Schenk, John H. McMasters: Procedure in Taxonomy 3rd Edition, p. 72, No. 228 Preview in Google Book Search

- ↑ Otto Frederik Müller: Fauna Insectorum Fridrichsdalina ... Copenhagen and Leipzig (Hafnia Lipsia) 1764 foreword p. XII

- ↑ Otto Frederik Müller: Zoologiae Danicae prodromus ... Hafnia (Copenhagen) 1776 p. 81, no. 874

- ↑ various authorship for Ptilinus

- ↑ Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature (48) June 2, 1991 Case 2292 [1]

- ↑ Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature (51) 1 March 1994 Opinion 1754 Ptilinus under point 5 (u)

- ↑ Ptilinus at Animalbase, accessed April 7, 2015

- ↑ Sigmund Schenkling: Explanation of the scientific beetle names (genus) in detail in the 2nd edition 1922

- ↑ WF Erichson et al .: Natural history of the insects of Germany 5th volume, part 1, Berlin 1877 p. 137

- ↑ Determination table at coleo-net

- ↑ a b c d James W. Munro: The Larvae of the Furniture-Beetles ... in Proceedings of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh Vol. 19 p. 220 Edinburgh 1915 drawing p. 228

- ^ A. Barbey: Traité d'Entomologie forestière à l'usage des forestiers .... Paris, Nancy 1913 p. 358

- ↑ a b c d Siegfried Cymorek: Genital shape, egg and oviposition as well as polymorphism of the first 4 larval stages of Ptilius pectinicornis (Coleoptera, Anobiidae) - an adaptation complex on wood cells. In: Verh. XIII. Int. Kongr. Entomol., Moscow 1968. Vol. 1, ZDB -ID 741546-1 , pp. 237-238.

- ↑ a b E. Chiappini, R. Nicoli Aldini: Morphological and physiological adaptation on wood-boring beetle larvae in timber Journal of Entomogical and Acarological Research, 2 Milano 2011 Vol. 43, No.. Doi : 10.4081 / jear.2011.47

- ↑ a b K. Escherich: Die Forstinsekten Mitteleuropas 2nd volume Berlin 1923 p. 191

- ^ S. Mark Henry: Symbiosis: Associations of Invertebrates, Birds, Ruminants od other Biota Vol. II Elsevier 2013 preview in the Google book search

- ↑ a b W. Kolbe: Contributions to the knowledge of the larvae of Silesian beetles in Zeitschrift für Entomologie, Verein für Silesian Entomology , 20th issue, Breslau 1895 p. 5f

- ↑ a b c d Siegfried Cymorek: About the mating behavior and the biology of the wood pest Ptilius pectinicornis L. (Coleoptera, Anobiidae). In: Negotiations XI. International Congress for Entomology 1960. Volume II 1962, ZDB -ID 741546-1 , pp. 335–339

- ↑ Cuvier (Ed.): The Animal Kingdom - Class Insecta 1st volume, Londen 1832 p. 350

- ↑ a b Siegfried Cymorek: contributions to the knowledge of life and the harmful occurrence wood-destroying insects. In: Zeitschrift Angewandte Entomologie , 55/1964 pp. 84–93

- ↑ Siegfried Cymorek: About the "combed Furniture Beetle" Ptilius pectinicornis (L.) (Col., Anobiidae) than wood destroyers, breeding object and Test insect . In: Holz-Zentralblatt , Stuttgart, ISSN 0018-3792 , Volume 96 (1970), No. 66 (June 3, 1970), p. 996 (also as a special edition).

- ↑ a b Richard Heß: The forest protection 3rd edition, 2nd volume Leipzig 1900 p. 16f

- ↑ a b Mina Mosneagu: The preservation of cultural heritage damaged by anobiids (Insecta, Coleoptera, Anobiidae) Academy of Romanian Scientists, Annals Series on Biological Sciences Vol 1, No.. 2 2012, pp. 32–65, ISSN 2285-4177 as PDF ( memento of the original from July 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ J. Th. Ch. Ratzeburg: Die Forst-Insecten 1st part, the Käfer Berlin 1939 p. 53

- ↑ Raoul von Dombrowski (Ed.): General Encyclopedia of All Forest and Hunting Sciences Volume 3, Vienna 1888 p. 121

- ↑ Macagno, Hardensen, Nardi, Lo Giudice, Mason: Measuring saproxylic beetle diversity in small and medium diameter dead wood: the grab-and-go method European Journal of Entomology 112 (3) doi : 10.14411 / eje.2015.049 ISSN 1210-5759 (print), 1802-8829 (online) as PDF

- ↑ Aurora Matei, Irina Teodorescu: Xylophagous Insect Species, Pest in Wood Collection from the Roumanian Peasant Museum Romanian Journal of Biology Vol. 56, No. 1 2011 p. 61ff as PDF ( memento of the original from July 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Livia Bucşa, Corneliu Bucşa: The Study of Biological Decay with Church Icons on Wooden Support Archived copy ( memento of the original from July 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Livia Bucşa, Corneliu Bucşa: Romanian Wooden Churches Wall Painting Biodeteriration p. 4 ( Memento of the original from July 1, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Georgiana Gămălie, Mariana Mustaţă: The attack of anobiids on books from the ecclesiastic patrimony European Journal of Science and Theology, Vol. 2, pp. 69–81 June 2006 p. 76

- ^ Whiteford L. Baker: Eastern Forest Insects US Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publication No. 1175, February 1972 p. 133

- ↑ Distribution map at FE ( Memento of the original from July 1, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved April 19, 2015

- ↑ Silva, Diamantino: New and interisting beetle (Coleoptera) records from Portugal Boletín Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa, nº 45 (2009) p. 279 Occurrence Portugal