Imperial Chancellor (German Empire)

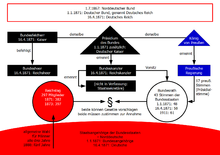

In the German Empire, the Chancellor was the executive at the federal level. So there was no collegial government, but only one official who had the function of a responsible minister . The office of the Reich Chancellor is identical to the Federal Chancellor of the North German Confederation . After the North German Confederation was renamed the German Empire on January 1, 1871, the "Federal Chancellor" also became " Reich Chancellor " on May 4, 1871 .

The Chancellor was appointed and dismissed by the German Kaiser . Formally, the emperor was free to decide whom to appoint and when and why to dismiss him. In practice, however, it was taken into account whether the Reich Chancellor could work with the Reichstag . Every act of the emperor had to be countersigned by the imperial chancellor , as it was known from other constitutional monarchies .

The office of Reich Chancellor is introduced very briefly in the Bismarckian constitution (as in the previous constitutions). There were no ministers as colleagues of the Reich Chancellor. The highest Reich authorities were headed by state secretaries. He could give instructions to these subordinate officials. Since there was no actual government, he was officially not a head of government, but the government in one person, according to Kotulla a "one-man government". They were therefore mostly called Reich Chancellors and State Secretaries "Reichsleitung". With brief exceptions, the Reich Chancellors were also Prime Minister of Prussia, which considerably strengthened their position of power.

The term of office of an Imperial Chancellor was per se indefinite and did not depend on new parliamentary elections or a change of emperor. The first Reich Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck , had been Federal Chancellor since 1867 . He was not released until 1890, which makes him the longest-serving chancellor in German history. The later Reich Chancellors served between four and nine years. Only in the First World War were the terms of office considerably shorter. The last two Chancellors, Georg von Hertling and Max von Baden , were appointed in consultation with the parliamentary groups and already presided over a coalition government.

Origin of the office

When the North German Confederation became an Empire, there was no reappointment of the official Bismarck: The German Chancellor is not the successor of the North German Chancellor, because both offices are identical. The name comes from the law firm; a chancellor is originally the head of a law firm, a kind of office in which documents are produced. There are historical models for the use of the word chancellor from Prussia, Austria, Switzerland and other countries.

Bismarck's draft of a federal constitution in 1867 envisaged a federal chancellor as an official who carried out the decisions of the Federal Council. It was only after a contradiction in the constituent Reichstag that it became a responsible minister. Initially, there were no authorities at the federal level, so that the Prussian Prime Minister and, more recently, North German Chancellor Bismarck, had to rely on the help of the Prussian authorities. During the time of the North German Confederation, until 1870, there were only two federal authorities: the Foreign Office for foreign policy and the Federal Chancellery for everything else.

Prussia and Empire

The history of the creation of the North German Confederation and its constitution had resulted in the Prussian Prime Minister (and Prussian Foreign Minister) becoming the most important politician at the federal level. The constituent state of Prussia comprised around four fifths of the North German Confederation and two thirds of the German Empire in terms of area and population. This had serious consequences for the functioning of federalism in Germany . In addition, according to the constitution, the Prussian king was automatically German emperor. Otherwise, the Prussian hegemony was constitutionally secured. Therefore, as Ernst Rudolf Huber states, "Reich policy was only possible with close agreement between the Reich leadership and the Prussian state leadership".

Nevertheless, Bismarck tried once to get rid of the burden of one of the offices. From December 21, 1872 to November 9, 1873, Albrecht von Roon served as Prussian Prime Minister. After this separation of offices had not proven itself, Bismarck was finally again Prime Minister. In the years 1892-1894 Chancellor Leo von Caprivi left the office of Prime Minister Botho Eulenburg . Even the last Chancellor of the German Empire, Max Prinz von Baden , was never Prime Minister of Prussia in his short term in October and November 1918 ( Robert Friedberg, Vice-President of his predecessor Hertling, served in his place ). There had been general concerns that an heir to the throne from Baden would serve as Prime Minister of Prussia.

But Bismarck, Caprivi and Prince Max were also always Prussian foreign ministers, which was important because the foreign minister instructed the Prussian votes in the Bundesrat (i.e. determined how the Prussian Bundesrat members had to vote). The only exception was Chancellor Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1894–1900), who left the Prussian Foreign Ministry to the State Secretaries in the Foreign Office Adolf Marschall von Bieberstein 1894–1897 and Bernhard von Bülow 1897–1900. The Prussian votes alone did not have a majority in the Bundesrat, but they usually formed the basis for Bundesrat resolutions. For an Imperial Chancellor in the Empire this was of particular importance: the Chancellor had few rights in the political system and although chaired the Bundesrat, he had no membership or vote of his own.

The Chancellor only gained power in the Bundesrat through the connection of offices, because as Prussian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister he determined the Prussian votes (which are called “presidential votes” in the constitution, even though they were Prussian votes). As a member of the Federal Council, he was given the right to speak in the Reichstag. Only the Federal Council and the Reichstag could introduce bills; a law required the approval of both bodies. In constitutional reality , it was the Reich Chancellor who presented draft bills to the Bundesrat in the name of the Reich leadership, not as a representative of Prussia.

The connection between offices led to the fear that the empire would become more “Prussian”. In fact, however, the opposite was the case: it was not the Prussian Prime Minister who directed the affairs of the Reich, but the German Chancellor who directed the affairs of the Prussian government. The Kaiser did not appoint the respective Prussian Prime Minister as Reich Chancellor, but instead appointed someone as Reich Chancellor, whom he then made Prussian Prime Minister. Half of the Reich Chancellors in the Empire did not come from Prussia: Hohenlohe and Hertling were of Franconian and Rhine-Hessian origin (and both previously served as Bavarian Prime Ministers), Bülow came from Holstein and Prince Max was the heir to the throne of Baden. German state secretaries were often Prussian ministers at the same time.

Development in the Imperial Era

It was not until 1871 that the number of State Secretaries and the highest Reich authorities grew, so that in practice the Reich leadership was more and more like a collegial government. The Reich Chancellor was responsible for the guidelines of politics , which he sought to assert in the Reich as well as in Prussia. A Prussian minister or a German state secretary was usually a personality who knew how to defend himself against the interference of the prime minister or the imperial chancellor. That limited its power.

Liberal politicians in the Reichstag called for a collegial government; a compromise with Bismarck then led to at least the Act of Representation in 1878 . The chancellor remained bound by the instructions of the state secretaries, but instead of the chancellor, the state secretaries could now countersign the emperor. Bismarck also appointed the free conservative Otto zu Stolberg-Wernigerode as general deputy (" Vice Chancellor "). He was not in charge of any supreme Reich authority and, viewed in this way, was not a subordinate of Bismarck. The Reichsleitung met from 1879 for consultative conferences, so, according to Huber, the "Reichsleitung openly assumed the character of a de facto college".

So there are signs that the Reich leadership slowly but steadily transformed into a collegial government. Bismarck had forbidden to speak of imperial government in official parlance. However, expressions such as Imperial Government were used in dealings with foreign countries , and in 1913 Vice Chancellor Clemens Delbrück said in the Reichstag that such a government already existed. Manfred Rauh also sees a creeping parliamentarization , i.e. the formation of a government based on coalitions in the Reichstag. Even without the crisis of World War I, this development could not be prevented in the long term. Michael Stürmer is more skeptical, according to which the parties and the entire nation have come to terms comfortably with the monarchical state. Therefore, even the Social Democrats would not have seen much use in parliamentarization.

End of the empire

Two weeks before the end of the Empire there was a serious constitutional change that affected the position of the Reich Chancellor. In the so-called October reforms of 1918, Art. 15, Paragraph 3 was changed: Since then, the Reich Chancellor has needed the confidence of the Reichstag to carry out his duties. In addition, the obligation to countersign was extended to include military orders from the emperor.

Chancellor Max von Baden urged the Kaiser to abdicate on November 9, 1918, because he feared a violent revolution in Berlin. Ultimately, without the consent of the emperor, he announced the abdication. Prince Max “transferred” his office as Chancellor to the Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert, although according to the constitution only the Kaiser could appoint a Chancellor. Ebert signed an appeal as Reich Chancellor; from November 10 to February 11, 1919, he was the actual head of government in Germany, however, only as one of two chairmen of the revolutionary council of people's representatives .

Compared to later constitutions

In the Weimar Republic there was also the office of Chancellor . However, according to the new Reich constitution , the Reich Chancellor became a part of the collegial Reich government alongside the Reich Ministers. The constitution confirmed the position of the Reich Chancellor, which continued to be prominent: The Weimar Reich Chancellor determined the guidelines of politics , presided over the cabinet and directed the affairs of the government. The Chancellor checked whether a minister was observing the guidelines, but was no longer authorized to issue instructions. In addition, resolutions of the Reich government required a majority of the votes in the cabinet. The Reich Chancellor and, at his suggestion, the Reich Ministers were appointed by the Reich President. The role of the Reich President was (also) reminiscent of that of the Emperor, who was responsible for appointing the Chancellor until 1918.

The Federal Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany is elected by the Bundestag . Otherwise his position is similar to that of the Reich Chancellor in the Weimar Republic. In the process of electing the Federal Chancellor, the Federal President has the right and the duty to propose a candidate to the Bundestag. This is a pale holdover from the time of the monarchy and the first republic.

Public officials

| Surname (Life data) |

Taking office | Term expires | cabinet | Remarks | image | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chancellor | ||||||

|

Prince Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898) |

May 4, 1871 | March 20, 1890 | I. | Resignation in conflict with Kaiser Wilhelm II. |

|

|

|

Count Leo of Caprivi (1831-1899) |

March 20, 1890 | October 26, 1894 | I. | Prussian general |

|

|

|

Prince Clovis of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1819–1901) |

October 29, 1894 | 17th October 1900 | I. | former Reich envoy (1848) and Bavarian Prime Minister |

|

|

|

Prince Bernhard von Bülow (1849–1929) |

17th October 1900 | July 14, 1909 | I. | Resignation after defeat in the Reichstag and conflict with the Kaiser |

|

|

|

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) |

July 14, 1909 | July 13, 1917 | I. | Resignation after conflict with the Supreme Army Command and the Reichstag |

|

|

|

Georg Michaelis (1857-1936) |

July 14, 1917 | November 1, 1917 | I. | Official without a power base |

|

|

|

Count Georg von Hertling (1843-1919) |

November 1, 1917 | September 30, 1918 | I. | Member of the Center Party , partly parliamentary government |

|

|

|

Prince Max of Baden (1867–1929) |

October 3, 1918 | November 9, 1918 | I. | brought about the end of the offices of emperor and chancellor |

|

|

See also

supporting documents

- ↑ Michael Kotulla : German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. Volume 1: Germany as a whole, Anhalt states and Baden , Springer, Berlin [u. a.] 2006, p. 279.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. Volume 1: Germany as a whole, Anhalt states and Baden , Springer, Berlin [u. a.] 2006, p. 279.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume IV: Structure and crises of the empire . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1969, p. 130.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume IV: Structure and crises of the empire . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1969, p. 130; ders .: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914–1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1978, p. 545 f .; Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806–1918. A collection of documents and introductions. Volume 1: Germany as a whole, Anhalt states and Baden, Springer, Berlin [u. a.] 2006, p. 279.

- ^ According to Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 801, p. 825.

- ↑ Manfred Rauh: The parliamentarization of the German Empire , Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 442.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume IV: Structure and crises of the empire . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1969, p. 136 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume IV: Structure and crises of the empire . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1969, p. 144.

- ↑ Manfred Rauh: The parliamentarization of the German Empire , Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 29 f.

- ↑ Manfred Rauh: The parliamentarization of the German Reich , Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 430.

- ^ Michael Stürmer: Government and Reichstag in the Bismarck State 1871–1880. Caesarimus or parliamentarianism. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1974.