Repatriation in Poland after World War II

The article outlines the resettlements of Poles from the former Polish Eastern Territories after the Second World War in the years 1944–1946.

history

The resettlement of large parts of the population from the old eastern areas of Poland was predominantly, if not only a consequence of the Second World War and the western shift of Poland desired by the Soviet Union . They were also a consequence of an old ethnic conflict that went back to the 19th century. It was the aim of both Great Britain and the Polish communists to bring about an end to the minority problem through a forced population exchange. The Polish communists felt obliged to the idea of a homogeneous Polish state also in the post-war era and in their integration policy towards the so-called repatriates. The integration policy in Poland was therefore less understood as a contribution to general society or social policy, but rather extended in terms of its objectives and the measures adapted to that effect to a nation-building state policy.

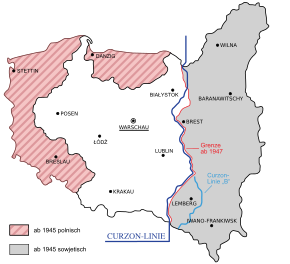

With this policy, the mixture of nationalities and denominations so typical of Eastern Central Europe was eliminated and aimed at transforming Poland and the states of the Lithuanians , Belarusians and Ukrainians that had arisen on the territory of the historic Polish Empire into homogeneous nation states. The introduction of the entire language areas of the Lithuanians, Belarusians and Ukrainians into the Soviet Union was only secured through the violent segregation of the peoples, and only then did the long controversial Curzon Line acquire the character of a real ethnic border.

At the same time, the relocation of the Polish nationality border to the Oder and Neisse rivers, as was actually carried out by the flight, resettlement and expulsion of the East Germans , created a nationally closed Polish state. Poland lost 180,000 km² of the pre-war national territory in the east and in return received the East German provinces and the Free City of Danzig , a total of 103,000 km², in which for the most part no significant Polish population was resident before.

The population or their nationality should be adapted to the new borders. In the west, this meant resettlement of almost the entire, almost exclusively German population, and resettlement of the Polish population from the east. The capture of East Germany and Danzig by the Polish state began on March 30, 1945, before the Potsdam Agreement with the creation of the Danzig Voivodeship , which was followed by the creation of the administrative districts of Masuria, Pomerania and Silesia. These parts of the country, officially called Reclaimed Areas , have been under a separate ministry since November 13, 1945, headed by Deputy Prime Minister Władysław Gomułka . The aim of this authority and thus for a long time the primary aim of Polish policy towards resettlers was to colonize the new Polish parts of the state.

Number of people relocated (1944–1947)

| Lp. | Origin of the relocated people | Estimate the number of people qualified for relocation | Estimation of the number of people emigrated to Poland | Percentage of people who have moved: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min. | Max. | min. | Max. | min. | Max. | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4th | 5 | 6th | 7th | 8th |

| 1 | Ukrainian SSR | 854,809 | 854,809 | 772.564 | 772.564 | 90.4% | 90.4% |

| 2 | Belarusian SSR | 520.355 | 535.284 | 226.315 | 273.502 | 42.3% | 51.1% |

| 3 | Lithuanian SSR | 379,498 | 383.135 | 171.158 | 197.156 | 45.1% | 51.5% |

| 4th | Other migrations (escape from the front in 1944, mobilization into the Berling Army 1944–1945) | --- | --- | 300,000 | 300,000 | --- | --- |

| 4th | Escape from the ethnic cleansing of the Ukrainian nationalists in 1942–1944 | --- | --- | 300,000 | 300,000 | --- | --- |

| All in all | 1,754,662 | 1,773,228 | 1,770,037 | 1,843,222 | |||

Reception in Poland

In relation to Polish history after the Second World War, the term had a special meaning.

Initially, the group of people resettled from the eastern areas of Poland was not referred to as repatriates , but rather to the more general term "evacuees". Both Polish and Soviet authorities used the term evacuation to refer to the resettlement of the East Polish population in 1944, and the representatives of the Polish government in the resettlement areas called themselves evacuation officers . In this context, it is also fitting that the PKWN ( Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego ) contracts with the Ukrainian, Lithuanian and Belarusian Soviet Republics, with which the mutual exchange of ethnic populations was decided in September 1944, were called evacuation contracts . However, in the same year, these Polish resettlers from the former eastern regions of Poland were called “ repatriants ” in the official language and the resettlements were officially called repatriations. There was also a state repatriation office that dealt with the resettlement of Poles. The misleading character of the terms has been pointed out in various places in the literature. For example, Fuhrmann writes:

" 520,000 Lithuanians, Belarusians and Ukrainians were" transferred "to the USSR from Poland, and 2.1 million Poles from the formerly Polish territories of the USSR, mostly to the" regained territories ". This "transfer", in German "Überführung", was usually an expulsion for those affected . They officially bore the strange name "repatriates", which can only be translated a little awkwardly as "those who have returned home". "

But these Poles did not actually return home from the ceded eastern territories. Meyer describes those as repatriates who were resettled from the eastern Polish areas ceded to the Soviet Union. Ther describes the possibly more appropriate character of repatriation:

“The cynicism of this term even surpasses the activist term for resettlers, because the Polish expellees were not returned to their original homeland, but removed from it. The "repatriates" did not return to the Patria [...], but were expelled to the formerly German eastern territories . The "expulsion abroad" marks an essential difference in the history of the Polish versus the German expellees [...]. "

If one looks at the Polish integration policy , it is important to distinguish the repatriates from other groups. The repatriates are first to be separated from the Polish re-emigrants. The re-emigrants were Poles who came back to Poland from the West, for example displaced persons or prisoners of war from Germany or as workers from France. The so-called autochthons form a third group . The majority of them were bilingual (German-Polish), had mostly Polish names and were considered by the new Polish state power to be actually Polish and only superficially Germanized. According to the Polish minority policy of the time, the autochthons seemed particularly suited to consolidating the Polish character of the territories they had won in the west. It was verified as Poland from 1945–1946 by a special commission and served the state and ethnic polonization of the acquired areas.

Integration policy towards the resettlers

The actual relocations were primarily characterized by considerable logistical difficulties and deficiencies. The transport of 787,000 people as part of the resettlements regulated in the Polish-Soviet evacuation agreements required considerable transport capacities. Complicating the large number of people to be transported was the fact that the contracts stipulated that the Poles would be allowed to take their household goods, furniture and all livestock with them. However, the Polish administration could not provide sufficient capacity of railway wagons for a relocation of this size. The consequence was that the resettlers often waited weeks and months at the loading stations, only to be transported away in open wagons afterwards. After these circumstances became known, many resettlers refused to actually set out on the path to the West so promised by the Polish leadership; and this despite the fact that they continued to be affected by the terrorist acts of the Ukrainian nationalists. With the help of the Red Army, the Polish state reacted with pressure against both the Ukrainians and the Poles unwilling to relocate: In order to combat the partisan actions of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), the security apparatus was expanded and the Polish People's Army strengthened with massive help from the Red Army . These forces have also been used to intimidate the population and control resettlements. In detail, this state pressure on the resettlers could be such that from autumn 1945 the authorities literally deported numerous people into the interior of the country, confiscated apartments including household items and furniture, had food cards blocked or simply used physical violence to force those unwilling to leave the country to register.

Attitude of the Polish state towards the resettlers

In view of such a form of resettlement, in which the resettlers viewed themselves more as objects of deportation than as subjects of resettlement, it remains to be asked what the general attitude of the Polish state was towards its so-called repatriates. The treatment of the resettled people initially corresponded to the assessment of the Polish authorities. The resettlers were seen as a poor or even destructive settlement element that was not able to do justice to Poland's tasks in the new western regions with a pioneering spirit and organizational talent. Behind this was the fear of the Polish communists that those resettled from eastern Poland might be enemies of real socialism and the Soviet Union. The resettlers, for their part, were in fact no friends of socialism, communism and collectivization because of their regional origin, their specific rural socialization and because of their experiences during the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland and disapproved of the collectivization-oriented Polish property and agricultural policy. In the suspicious assessment of the resettlers by the Polish authorities, the memory of their social origins - landed nobility and bourgeoisie, or Catholic-conservative rural population - probably played a not unimportant role. The conscious break with all traditions of the Second Polish Republic was, however, a first goal of communist social policy, especially the settlement policy of the Ministry for the Reclaimed Territories . The negative assessment of the resettlers by the official bodies only turned into obvious praise at the moment when those on whom Polish policy had placed great hopes in the Polonization of the new western areas, namely the resettlers from central Poland, turned out to be a disappointment: one a large number of central Poland turned their backs on the former German provinces and moved to their old homeland. The remaining resettlers from the former eastern Poland have now been recognized as a permanent settlement element.

The aim of communist social policy was the break with the Second Republic and the creation of an ethnically homogeneous state. The primary goal of the policy towards the resettlers in the new western areas was therefore rapid integration and assimilation into the newly created communist-Polish society. However, the Polish government did not regard the integration of the resettlers as an end in itself or the state's primary task; rather, this seemed to her to be the task of the resettlers themselves. It was seen as the obligation of the former eastern Poles to secure the new western areas for the new Polish state through their mere presence and to polonize them culturally. At the beginning of the integration was the naturalization of the resettlers. Ther explains how this took place in the various specific cases:

“In the case of the Polish displaced persons, recognition as a Polish citizen was relatively simple and prescribed by the evacuation or repatriation contracts. As a result of the evacuation, Soviet citizens of Polish or Jewish descent who had been Polish citizens on September 1, 1939 and on whom the Soviet Union had imposed Soviet citizenship after the annexation of the Polish eastern territories automatically exchanged Soviet for Polish citizenship . In Lithuania, ethnic Poles who had been Lithuanian citizens before the world war were also allowed to report for evacuation. "

In the foreground of Polish politics was not so much the egalitarian social policy common in other Eastern bloc states ; Instead, the focus of Polish communism was on specifically Polish nationalism, as it had developed on the basis of historical experience with its neighbors in general and on the basis of the armed conflicts with neighbors in the course of the Second World War in particular. The word " nation " came to the fore in the vocabulary of Polish communists before other sociopolitical or class terms. This Polish nationalism of communist color found its particular expression in the doctrine of the regained territories, in which one spoke not of the polonization of the former German eastern provinces, but of their repolonization and thus assumed that the entire area had ever been in Polish hands. Communist propaganda gave the repatriates the impression that after centuries of foreign rule they were settling back into original Polish land for the first time. The social policy of Poland towards the repatriates, unlike, for example, the expellee policy in the Soviet Zone / GDR towards the German expellees, did not have equalizing objectives . The settlement of the Regained Territories ( Ziemie Odzyskane ) was described as a national task, as a pioneering service to the Polish nation.

Polish integration policy measures

The overriding principle of all measures of Polish politics was that the repatriants were not treated differently from other resettlers and re-emigrants, with the result that the relative material disadvantages suffered by the former residents of the Polish eastern areas as a result of the resettlement in the new western areas were not compensated . In general, a wide range of measures was applied in integration policy. It encompassed both indirect and direct redistribution policies and the redistribution of resources.

The social charity orientation of the integration policy towards the resettlers enabled them to enjoy a modest standard of living, which, however, could not be compared with the higher standard of living of the rest of the population of the new Polish state. This can be seen as a direct consequence of the abandonment of a socio-political alignment goal in Polish integration policy. A redistributive character in Poland's integration policy was much less apparent than in the GDR's policy of expellees. The People's Republic initially benefited from the fact that extensive assets were available for redistribution due to the expropriation of the German population, but these redistributive policies in Poland were drastically reduced in 1946 because the state government maintained the status quo in the distribution of property confirmed the new western territories.

In general, however, it can be said that there were resettlers in 1948 who, as a result of the measures taken by Polish policy, lived better than they did in 1945 in their old home in eastern Poland or when they arrived in the western regions immediately. With the onset of Stalinism in Poland in 1948 and the associated social and economic changes, however, much of the economic progress made by the repatriates was lost again. Overall, in the course of the entire policy change in Poland, integration policy increasingly left its constructive basis and became repressive.

nationality

In 1938, 75,000 Polish emigrants - mostly Jews - who had been living abroad for more than five years had their Polish citizenship revoked on the basis of the law on citizenship revocation of March 31, 1938 . In the Law on Polish Citizenship of January 8, 1951 , the legal effect of such a withdrawal against persons who were resident in Poland on the day this law came into force was abolished. With the law on Polish citizenship of February 15, 1962 , all those who had come to Poland as repatriates later acquired Polish citizenship by virtue of the law .

Network addresses

Individual evidence

- ↑ Przesiedlenie ludności polskiej z Kresów Wschodnich do Polski 1944-1947. Wybór dokumentów , Warszawa: Neriton, 2000

- ↑ Grzegorz Hryciuk: Wysiedlenia, wypędzenia i ucieczki 1939-1959. Atlas ziem Polski.

- ↑ Zofia Kurzowa: Język polski Wileńszczyzny i Kresów północno-Wschodnich.

- ↑ Repatriacje i migracje ludności Pogranicza w XX wieku . In: Wspólne dziedzictwo ziem północno-wschodnich dawnej Rzeczypospolitej . No. III . Białystok 2004, ISBN 83-920642-0-8 , p. 111 ( gov.pl [PDF]). Repatriacje i migracje ludności pogranicza w XX wieku ( Memento of the original from May 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Dieter Gosewinkel: Protection and Freedom? Citizenship in Europe in the 20th and 21st centuries , Suhrkamp Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-518-74227-3 . P. 161 .

- ^ Law of January 8, 1951 on Polish citizenship (Journal of Laws of January 19, 1951). In: yourpoland.p. Retrieved February 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Polish Nationality Act of 1962. In: yourpoland.pl. Retrieved February 27, 2017 .

literature

- Manfred M. Alexander: Small history of Poland . Reclam, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-15-010522-6 .

- Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg: The Polish-Ukrainian Relations 1922-1939. A literature and research report . In: Yearbooks for the History of Eastern Europe / New Series Vol. 39 (1991), pp. 81-102.

- Andrzej Chojnowski: Koncepcje polityki narodowościowej rządów polskich w latach 1921–1939 . ZNIOW, Breslau 1979, ISBN 83-04-00017-2 .

-

Winston Churchill : His complete speeches 1897-1963 . Chelsea House, London 1974.

- 7. 1943-1949 . 1974.

-

Norman Davies : God's Playground. A history of Poland . OUP, London 2005.

- 2. 1795 to the present . 2005, ISBN 0-19-925340-4 .

- E. Dmitrov: Escape, expulsion, forced resettlement . In: Ewa Kobylińska u. a. (Ed.): Germans and Poles. 100 key words . Piper, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-492-11538-1 , pp. 420-427.

- Piotr Eberhardt: Przemiany narodowościowe na Ukrainie XX wieku . Polish Academy of Sciences , Warsaw 1994, ISBN 83-903109-0-2 .

- Rainer W. Fuhrmann: Poland manual. History, politics, economics . Fackelträger-Verlag, Hanover 1990, ISBN 3-7716-2105-4 .

- Ryszard Gansiniec: Na straży miasta, Karta 13 . Warsaw 1994.

- Andreas R. Hofmann: Post-war period in Silesia. Social and population policy in the Polish settlement areas 1945–1948 . (Contributions to the history of Eastern Europe; Vol. 30). Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-07499-3 .

- Krystyna Kersten: Polska - państwo narodowe. Dylematy i rzeczywistość . In: Narody. Jak powstawały i jak wybijały się na niepodleglość . Warsaw 1989, pp. 442-497.

- Enno Meyer: Basics of the history of Poland . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-04371-5 .

- Hans Roos: History of the Polish Nation. 1918-1985. From the founding of the state in World War I to the present day . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-17-007587-X .

- Michał Sobkow: Do innego kraju, Karta 14 . Warsaw 1994.

- Tomasz Szarota : Osadnictwo miejskie na Dolnym Sląsku w latach 1945-1948 . ZNIOW, Wroclaw 1969.

- Philipp Ther : German and Polish expellees. Society and policy of expellees in the Soviet Occupation Zone / GDR and in Poland 1945–1956 (= critical studies on historical science . Volume 127). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-525-35790-7 .

- Ryszard Torzecki: Polacy i Ukraińcy. Sprawa ukraińska w czasie II wojny światowej na terenie II Rzeczypospolitej . PWN, Warsaw 1993, ISBN 83-01-11126-7 .

- Jan Tyszkiewicz: Propaganda Ziem Odzyskanych w prasie Polskiej Partii Robotniczej w latach 1945-1948 . In: Przegląd Zachodni , Vol. 4 (1995), pp. 115-132.