South African English

| South African English | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

South Africa | |

| speaker | 3–4 million (native speakers), population mostly second speakers | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | South Africa | |

South African English ( SAfEng for short ) is a variety of the English language spoken in South Africa . South African English is characterized by a pronunciation that is in part influenced by the first languages of the various ethnic groups. Furthermore, the vocabulary of South African English contains loan words from the languages with which it is in contact, in particular Afrikaans and Zulu .

A distinction is made between different variants of South African English, which are spoken by different population groups and which differ from one another primarily in their pronunciation. The main variants of South African English are White South African English , Black South African English, and Indian South African English . There are also some more locally restricted variants such as Cape Flats English for the working class of Cape Town.

history

The history of English in South Africa begins with the settlement of the Cape region by British settlers in 1820. Approximately 4,500 settlers from all parts of Great Britain were settled in order to establish the Cape of South Africa as a British colony. Other British settler groups followed in the 1840s and 1850s, mostly settling in Natal . In addition to European immigrants, Indian immigrants also came in the 19th century, who were recruited as workers for the plantations in Natal. Most Indian immigrants brought their native Indian language with them, but also learned English as a second language . When gold and diamonds were found in Witwatersrand and other regions of South Africa, more European immigrants came as a result of the gold rush. In the last quarter of the 19th century, around half a million Europeans immigrated, many of them English-speaking.

With their immigration and colonial policies, the British were in competition with the Netherlands , which were also interested in southern Africa and had had trading posts there since the 18th century. The number of Dutch settlers speaking a variant of Dutch that evolved into today's Afrikaans far exceeded the number of British immigrants. The European immigrants also met African tribes in the various regions of South Africa, which were usually suppressed or ousted by the Europeans.

The conflicts of interest between the British and the Dutch led to various armed conflicts in the course of the recent history of South Africa (e.g. the Second Boer War 1899-1902), with the British initially having the upper hand. In 1910 the Cape Colony, Natal, Transvaal and the Orange River Colony were united to form the Union of South Africa . South Africa received the status of a British Dominion . With the dissolution of the British colonial empire , many Dominions gained their independence after the Second World War, including South Africa, which in 1961 declared itself the Republic of South Africa / Republiek van Suid-Afrika (RSA) and left the Commonwealth of Nations .

Politics in the Republic of South Africa from 1961 onwards was mainly dominated by the National Party , whose apartheid policy aimed at strict racial segregation between whites and other population groups. Among other things, so-called " homelands " were set up for the African population groups , which were given a certain degree of autonomy. With the establishment of the homelands, the division of South Africa into a "white" South Africa, consisting of the Cape Province, Natal, Transvaal and the Orange Free State, and a "black" South Africa, consisting of the homelands, should be promoted. With the end of apartheid in 1994, this policy of racial segregation and discrimination ended.

The changeful history of South Africa and the composition of the population from different ethno-linguistic groups also led to a changeful history of the English language in South Africa:

With the dominance of the British in trade, economy and politics in the 19th century, the English language experienced an upswing. Although native English speakers were a minority in South Africa, English became the dominant language in industry, commerce and public transport. Dutch and Afrikaans became less important because well-paid, prestigious jobs were linked to knowledge of the English language. Indian immigrants, blacks and colored people preferred English as a second language, so that second language variants of English such as Black South African English emerged.

With the declaration of the Republic of South Africa and the dominance of Afrikaans speakers in politics, English was pushed back in favor of Afrikaans, especially in administration and education. The administration's recruitment policy favored Afrikaans speakers, and the role of Afrikaans as an official communication tool was promoted. In addition to the existing English-speaking universities , three Afrikaans-speaking universities were established after 1948.

Apartheid policy in the Republic of South Africa also included various language policies aimed at maintaining awareness of ethnic differences among all population groups. Among other things, it was stipulated that, as a rule, all population groups were taught in their mother tongue in the first few years of their schooling, with English and Afrikaans being added as second languages. This policy was tough especially for the black population of South Africa, because they had to learn two other languages, namely English and Afrikaans, in elementary school. Furthermore, the apartheid regime tried to impose Afrikaans as the only language in upper secondary schools in the "white" parts of South Africa, against the opposition of the black population, who preferred English as it was the language of most higher education institutions. The conflict over the language regulation finally erupted in the 1976 uprising in Soweto , whereupon the government also allowed English as the sole language of instruction in the upper grades of schools.

With the end of apartheid, English experienced a renewed rise. Afrikaans was experienced as the language of oppression by the non-white population, while English was perceived as the language of emancipation . B. also used by the African National Congress . Afrikaans is now only one of a total of 11 official languages in the Republic of South Africa. English is the dominant language in secondary and higher education. English also serves as the lingua franca between the various population groups and is the language of international politics, business and commerce.

Geographical distribution

English has been spoken in South Africa since the 1820s. It is an official language in the Republic of South Africa and is spoken by a large part of the population as a first or second language. Variants of English, similar to South African English, are also spoken in Zimbabwe , Namibia , Zambia, and Kenya . The majority of speakers who speak English as their first language are concentrated in the Western Cape , Gauteng, and KwaZulu-Natal .

Official status

Although English is only one of eleven official languages in the Republic of South Africa and is spoken as a mother tongue by only 11.04 percent of the population over the age of 15 (as of 2015), alongside Afrikaans and Zulu it plays the role of a lingua franca , which allows the speakers of the many different language and cultural groups in the country to communicate with one another.

In addition, English is the only South African language widely spoken abroad, and thus it serves as the language in international trade, academia, politics, and the entertainment industry.

Dialects and sociolects

Linguistic research distinguishes between white South African English, spoken by the descendants of British and Dutch settlers, black South African English, spoken by the descendants of black residents of South Africa, and Indian South African English, spoken by the descendants of Indian immigrants in South Africa.

terminology

The distinction between “blacks”, “whites”, “coloreds” and “Asians” is quite problematic, because during the apartheid period the division of the population into different population groups was enforced and was the basis for a policy of strict racial segregation and discrimination. However, due to the lack of alternatives, it is difficult to describe ethnic and ethnolinguistic groups with unencumbered terms. Furthermore, the effects of apartheid on the language of the various population groups are so significant that there is a correlation between ethnic group and South African dialect. For these reasons, terms such as "white / black South African English" are still used in linguistics, but without wanting to continue the classifications of the apartheid regime.

White South African English

In principle, one has to distinguish between speakers of English as a first and second language. The percentage of the population who speak English as a first language, usually descendants of British settlers, is more or less approaching British English, with the standard British pronunciation, Received Pronunciation , enjoying high social prestige ( Cultivated White South African English ). In the meantime, however, a standard of South African English has developed that is also enjoying a high level of acceptance ( General South African English , General White South African English or Respectable White South African English ). There are also speakers of English whose sociological background is more of a working class and possibly ancestry from an Afrikaans-speaking family. These speakers use Broad South African English , an English that is a native speaker but is close to Afrikaans English , which is spoken as a second language by Afrikaans speakers.

The language competence of speakers of English as a second language varies greatly, from mother tongue competence (bilingualism) to English that is strongly influenced by the first language Afrikaans ( Afrikaans English ).

Black South African English

Black South African English denotes the variety of English used by black speakers of English as a second language in South Africa. Due to the separation of black, white and other population groups in educational institutions during the apartheid period, black South African English has developed as a special variety of South African English. The main difference between British English and white South African English is in pronunciation. Black South African English was previously a second language alongside an African language for most speakers. This is slowly beginning to change with the end of apartheid and the rise of a black middle class. There is a small group of black South Africans who speak English as their mother tongue. In terms of pronunciation and syntax, however, they are more based on Cultivated or General South African English , so that they cannot be called speakers of black South African English.

Black South African English is actually a continuum, so a distinction is often made between a mesolect and an acrolect , similar to other varieties of English spoken as a second language. While the mesolect is more closely related to standard English (in South Africa the British or the more prestigious white South African English), the acrolect deviates more from the standard, especially in pronunciation, and is usually influenced by the speaker's African mother tongue.

The prestige of black South African English has long been lower than that of white South African English, which has become a quasi-standard. In the meantime, however, it has been observed that black South African English is becoming increasingly acceptable in informal educational contexts.

Indian South African English

Indian South African English is the English used by Indian immigrants in South Africa and their descendants. While Indian South African English was learned in the first generation of immigrants as a second language alongside an Indian mother tongue, it is now spoken as a first language (mother tongue). Indian South African English is now to be regarded as a separate variety of English and differs from Indian English , which is spoken in India . Indian South African English is influenced by General South African English , a permanent contact with Indian English, by Indian languages of the first generation of immigrants and by regional South African English variants, especially in KwaZulu-Natal .

Other variants

Other variants of South African English are mostly socially and regionally limited, such as Cape Flats English to the working class of Cape Town.

Phonetics and Phonology

The main difference between South African English and other variants of English, such as British or American English, is how it is pronounced. Although consonant and vowel phonemes often match in British and South African English, there are a number of deviations and variations in South African English, some of which are also specific to white, black and Indian South African English.

Consonants

The consonant system of South African English is similar to that of British English , but with the following differences:

- South African English has a velar fricative / x / as an additional phoneme , which is used in loan words from Afrikaans (e.g. gogga ; 'insect, beetle') or loan words from Khoisan .

- In Broad South African English and Afrikaans English , [θ] is typically implemented as [f]. In black South African English, [θ] tends to be replaced by [t], [ð] by [d]. In Indian South African English, instead of [θ] and [ð], [t̪] and [d̪] are used.

- In Indian South African English, [t] and [d] are occasionally replaced by the retroflex variants [ʈ] and [ɖ], but the retroflexes are not as common as in Indian English and their use is on the decline.

- The voiced consonants / v, ð, z, ʒ / become voiceless at the end of the word in white South African English.

- Aspiration is typical of southern Bantu languages and influences the pronunciation of black South African English: plosives at the beginning of syllables are regularly aspirated, especially by speakers of the mesolect.

- The implementation of the affricates / tʃ, dʒ / is very variable in black South African English, / tʃ / mostly as [ʃ] and / dʒ / often as [dʒ] or [ʒ].

- Speakers with a South Indian (Dravidian) background tend to leave out [h] at the beginning of the word (H-dropping): [ʕæt] instead of [hæt] for has .

- / r / is pronounced postalveolar by some speakers as in British English, other realizations are retroflex [ɹ], [ɾ] or a trill [r], especially in the mesolect of black South African English. South African English, like British English, is non-Rhotic .

Vowels

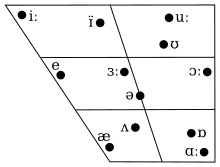

The vowel inventory of South African English is similar to that of British English, but there are some variations that are characteristic of South African English.

Monophthongs

The most distinctive feature of white South African English is an allophone variation of the vowels in words like kit and bath . While [ɪ] is used in combination with velars and palatals, in all other contexts the sound is realized more centrally than [ï]. This has also been observed for Indian South African English. A vowel that is more open and behind is used for bath in General and Broad White South African English .

Black South African English uses the monophthongs / i, ɛ, a, ɔ, u /. Like many African varieties of English and in contrast to British English ( Received Pronunciation ), it makes no distinction between tense and lax vowels, the length of which depends on the consonant that follows them. So there are z. B. no distinction between [i] and [ɪ].

The monophthongs of Indian South African English are closer to the pronunciation found in British Received Pronunciation than to the pronunciation of General White South African English .

Diphthongs

There is a tendency in South African English to monophthongize diphthongs. Typical for white South African English are monophthongizations of [aʊ] ( mouth ) and [aɪ] ( price ) to [a:] (ie [ma: θ] and [pra: s]). A tendency towards monophthongization was also observed in black South African English. In Indian South African English, on the other hand, the diphthongs are realized more like in British English, with the exception of [wie] (as in square ), which is monophthongized to [e:] in Indian South African English as well as in General White South African English .

Emphasis

So far, there has been little systematic research into the emphasis on South African English. Black and Indian South African English are said to have a syllable-counting rather than an accent-counting speaking rhythm. According to individual observations, Indian South African English tends to be spoken at a high speed and an intonation that differs from that of white South African standard English.

grammar

South African English differs from British and American variants of English mainly in its pronunciation and vocabulary, rather than in its grammar. However, if you look primarily at the variants of South African English such as Broad White South African English or the black and Indian South African English, you will find constructions that are typical of English in South Africa.

White South African English

Some examples specifically of white South African English are:

In Broad White South African English are found using is it? as frequent queries instead of the question tags usually used in British and American English :

- He's gone to town. - Oh is it? (Default: Oh, has he? )

Adjectives that are typically supplemented by of + participle are instead supplemented with to + infinitive:

- This plastic is capable of withstand heat. (Standard: This plastic is capable of withstanding heat. )

The preposition by often replaces at or similar prepositions:

- He left it by the house (Standard: at home )

- We bought it by the butcher's

The construction be busy + V- ing is used as a substitute for the progressive form, also with semantically opposing verbs such as relax :

- We were busy listening to the radio

- I'm busy relaxing

If the context makes the meaning sufficiently clear, objects can be omitted from transitive verbs:

- Oh good, you've got.

- Did you bring?

Furthermore, no is often used to express an affirmation or surprise:

- How are you?

- No, I'm fine.

- She's getting big, hey?

- No, she is!

The influence of Afrikaans on South African English is often made for the deviating syntax, although some linguists point out that some of the constructions could also be traced back to the non-standard English of the first English settlers in the 19th century.

Black South African English

Black South African English differs more from British or American standard English in its pronunciation, but there are some syntactic constructions that are typical of black South African English. Here it is more similar to other second language variants of English such as B. English in East Africa.

be + V- ing is used in contexts that would not be allowed in standard British English:

- People who are having time for their children ...

- Even racism is still existing ...

In the case of modal verbs, the most striking phenomenon is the use of can be able , which is also found in other parts of Africa:

- ... how am I going to construct a sentence so as this person can be able to hear me clearly

Black South African English also uses that more often than British English in some contexts, which tends to omit it here:

- As it has been said that history repeats itself.

- (British English: As it has been said, history repeats itself. )

Typical of black South African English is also the frequent use of topicalization , i.e. H. Sentences are prefixed for emphasis:

- Today's children, they are so lazy.

Indian South African English

Indian South African English is also characterized by some non-standard constructions; partly these are similar to the (white) General South African English , partly they are also due to the influence of Indian languages.

In some contexts, the form of be can be omitted in Indian South African English :

- Harry not here.

- My brother that! (= That's my brother. )

There is a great deal of variability in relative clauses in Indian South African English. In addition to relative clauses, as can also be found in standard English, there are also constructions that can be traced back to the influence of Dravidian languages (correlatives):

- Which-one I put in the jar, that-one is good.

- (Standard: The ones (ie pickles) that I put in the jar are the best. )

One of the most striking features of Indian South African English is the use of y'all (= you all ) as the second person plural, also as yall's possessive pronouns :

- Is that yall's car?

- (Standard: Is that your (pl.) Car? )

As in black South African English, there are also many examples of topicalization:

- Change I haven't got.

vocabulary

Through contact with other languages in South Africa, many words from other languages have found their way into South African English. Examples of loan words from African languages are:

- impi (from the Zulu, dt. 'war group, group of armed men')

- indaba (Zulu, Xhosa, dt. 'meeting, business')

- gogo (Xhosa, Zulu, German 'grandmother')

- mamba (from Bantu imamba , dt. '(poisonous) snake')

- suka (Zulu, 'to go away')

The loan words from Afrikaans include:

- koppie ( eng . 'small hill, mountain')

- dorp (dt. 'village')

- veld (Eng. 'open, flat land')

- Afrikaner (Eng. 'Afrikaans-speaking white person in South Africa')

- apartheid

There are also some South African expressions that differ from British and American English, e.g. B. bioscope (British English: cinema ), location (BritE: ghetto ), robot (BritE: traffic light ) and reference book (German 'identity document, ID card').

Indian South African English also includes a large number of loanwords from Indian languages and other sources. However, only a few of these loan words have found their way into common parlance outside of the Indian community. These include mainly terms from Indian cuisine such as dhania (English: 'coriander') or masala ('ground spices').

Examples

The following audio sample contains examples of South African regionalisms and slang spoken by a second language speaker:

research

The research focus on South African English has expanded considerably since the end of apartheid in the 1990s. Originally the research interest was initially in South African English as spoken by native speakers, its characteristics and its development into a new standard. This was increasingly followed by studies on black and Indian South African English, especially since both had developed into independent variants of South African English. This was also done in the context of research on English varieties worldwide, including other varieties in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean, which came more into focus in English studies ( New Englishes ). After the end of apartheid in South Africa, questions of the standardization of individual English versions, questions of education and language policy in South Africa also moved more into focus.

See also

literature

General descriptions and grammars

- Vivian de Clerk (Ed.): Focus on South Africa ( Varieties of English Around the World ). John Benjamin, Amsterdam 1996, ISBN 978-1-55619-446-7 .

- Klaus Hansen, Uwe Carls, Peter Lucko: The Differentiation of English into National Variants: An Introduction . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-503-03746-2 .

- Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Language in South Africa . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2002, ISBN 978-0-521-79105-2 .

- LW Lanham, CA Macdonald: The Standard in South African English and Its Social History . Julius Groos, Heidelberg 1979, ISBN 3-87276-210-9 .

- Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 .

- Peter Trudgill, Jean Hannah: International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English , 5th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-340-97161-1 .

Dictionaries

- Joyce M. Hawkins (Ed.): The South African Oxford School Dictionary. 16th edition. Oxford University Press Southern Africa, Cape Town 2003, ISBN 0-19-571414-8

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Trudgill, Jean Hannah: International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English . 5th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-340-97161-1 , pp. 33 .

- ^ David Crystal: English as a Global Language . 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-53032-3 , pp. 43 .

- ↑ Klaus Hansen, Uwe Carls, Peter Lucko: The differentiation of English into national variants: An introduction . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-503-03746-2 , pp. 192-193 .

- ↑ Klaus Hansen, Uwe Carls, Peter Lucko: The differentiation of English into national variants: An introduction . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-503-03746-2 , pp. 193-194 .

- ↑ Klaus Hansen, Uwe Carls, Peter Lucko: The differentiation of English into national variants: An introduction . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-503-03746-2 , pp. 192-198 .

- ^ Sean Bowerman: White South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 168 .

- ↑ Peter Trudgill, Jean Hannah: International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English . 5th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-340-97161-1 , pp. 33 .

- ^ Institute of Race Relations : South Africa Survey 2017 . Johannesburg 2017, p. 74

- ^ Sean Bowerman: White South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 168 .

- ^ Sean Bowerman: White South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 164 .

- ^ Bertus von Rooy: Black South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 177-179 .

- ↑ Rajend Mesthrie: Indian South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 188-191 .

- ^ Peter Finn: Cape Flats English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 200-222 .

- ^ Sean Bowerman: White South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 164-1776 .

- ^ Bertus von Rooy: Black South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 177-187 .

- ↑ Rajend Mesthrie: Indian South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 188-199 .

- ↑ Rajend Mesthrie: Indian South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 195-196 .

- ↑ Klaus Hansen, Uwe Carls, Peter Lucko: The differentiation of English into national variants: An introduction . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-503-03746-2 , pp. 201-202 .

- ↑ Peter Trudgill, Jean Hannah: International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English . 5th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-340-97161-1 , pp. 35 .

- ↑ Sean Bowerman: White South African English: morphology and syntax . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 472-487 .

- ↑ Rajend Mesthrie: Black South African English: morphology and syntax . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 488-500 .

- ↑ Rajend Mesthrie: Indian South African English: morphology and syntax . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 501-520 .

- ↑ Peter Trudgill, Jean Hannah: International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English . 5th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-340-97161-1 , pp. 36 .

- ↑ Klaus Hansen, Uwe Carls, Peter Lucko: The differentiation of English into national variants: An introduction . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-503-03746-2 , pp. 199-201 .

- ↑ Sean Bowerman: White South African English: morphology and syntax . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 484-485 .

- ↑ Rajend Mesthrie: Indian South African English: phonology . In: Rajend Mesthrie (Ed.): Varieties of English: Africa, South and Southeast Asia . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019638-2 , pp. 190 .

- ↑ ZBLW Lanham, CA Macdonald: The standard in South African English and its social history . Groos, Heidelberg 1979, ISBN 3-87276-210-9 .

- ^ Ute Smit: A New English for a New South Africa? Language Attitudes, Language Planning and Education . Braumüller, Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-7003-1126-5 .