Savannah armadillo

| Savannah armadillo | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

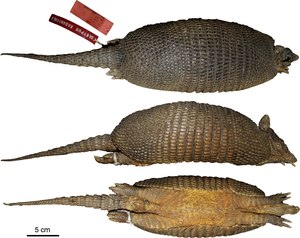

Savanna armadillo ( Dasypus sabanicola ), holotype specimen |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Dasypus sabanicola | ||||||||||||

| Mondolfi , 1968 |

The savannah armadillo ( Dasypus sabanicola ) is a small species of armadillos and lives in the savannahs of the Llanos in northern South America . However, the independence of the armadillo species has not been clarified, which requires further research. The solitary animal feeds mainly on insects and is diurnal. The stock is considered safe.

features

Habitus

The savannah armadillo reaches an average length of 49.3 cm, of which the tail, which is quite broad at the base, takes up about 18.5 cm. The tail has about two thirds of the body length. It is relatively short, longer than the seven-banded armadillo ( Dasypus septemcinctus ), but shorter than that of the nine-banded armadillo ( Dasypus novemcinctus ). The body weight is 1.4 to 1.5 kg. Thus, the armadillo is a smaller representative of the long-nosed armadillos and is about as large as its southern relatives, the seven-banded armadillo or the southern seven-banded armadillo ( Dasypus hybridus ). The head measures around 7 cm, the ears are 2.7 cm long and comparatively short. The characteristic armor on the back is divided into three parts, with a fixed shoulder and a pelvic part as well as an average of 8 movable ligaments connected by skin flaps in between, sometimes there is a ninth ligament, which is only movable at the armor edges. The number of moving bands is thus slightly higher than in the two seven-banded armadillos species. The movable ligaments are composed of small, square bone platelets, of which the fourth has between 46 and 53 (an average of 50). The more solid armor parts, on the other hand, consist, typical of the long-nosed armadillos, of rounded bone plates. The carapace is generally darker than that of the nine-banded armadillo. The color on the back appears cloudy black, towards the edges light brown or gray-white. The short legs have four rays at the front and five at the back, each ending in claws.

Skull and skeletal features

The length of the skull is 7.2 cm, it is 3 cm wide at the zygomatic arches , and only 1.9 cm at the constriction behind the eye windows . Overall, the skull looks relatively small, the rostrum is rather short compared to the other representatives of the long-nosed armadillos. As with all armadillos, the savannah armadillo's teeth also differ from those of the rest of the mammals . The teeth are all molar-like and have a stake-like construction, and they also have no tooth enamel . In the upper jaw there are 7 to 8 teeth per jaw half, in the lower jaw 8, so a total of 30 to 32. In young animals there are sometimes only a total of 6 teeth per jaw arch. The length of the upper row of teeth is 1.9 cm.

distribution and habitat

The area of distribution of the savannah armadillo is in northern South America , here it occurs from the northwest of the state of Bolivar in Venezuela to Colombia in the lowlands east of the Andes , but it does not colonize the areas of the Gran Sabana . The entire distribution area covers 445,000 km², the actually inhabited area is unknown, as is the size of the population. The habitat includes the open savannah and shrubbery landscapes of the Llanos , here the species primarily prefers habitats with sandy or loamy soils with vegetation of sweet grasses such as andropogon , sporobolus or trachypogon . It can be found at heights of 25 to 200 m above sea level, sometimes it also occurs at the edges of forests and gallery forests . It is usually more common in intact natural landscapes, but the savannah armadillo is generally rare.

Way of life

Territorial behavior

The savannah armadillo lives as a solitary animal and, unlike most other armadillo species, is diurnal; the main activity times include the early morning hours until around 9:00 a.m. and the late afternoon from 4:00 p.m. This is possibly due to the rather constant temperatures of around 27 ° C in the savannas. It uses action spaces ( home ranges ) with a size of 1.7 to 11.6 hectares. There, the armadillo creates highly branched underground burrows with several entrances. In front of these nests are built from plant material, which on the one hand serve to protect the young animals and on the other hand from possible flooding.

nutrition

The diet consists mainly of insects . Stomach contents from Venezuela were composed of 45% termites , 22% ants and 18% beetles such as scarab beetles . In addition, remains of grasshoppers , including field locusts , and earthworms could be detected. Similar studies in Colombia even showed up to 88% termites and 10% ants, the proportion of beetles was 1%. Representatives of the termite family Rhinotermitidae predominated, with mostly workers being eaten. Furthermore, the uptake of sand and clay promotes the mineral balance.

Reproduction

The fertilization usually takes place in April and May, the young are then brought into the world from August to September. As a rule, a litter contains four young who are genetically identical due to polyembryony . The interval between two birth cycles is about a year. During rearing, the young spend part of the time in the nests in front of the entrances to the burrows, while the mother animal searches for food nearby.

Predators and parasites

Predators are known, among other things, with the jaguarundi , but this has only rarely been observed. The most common external parasites include ticks of the genus Amblyomma An internal parasites are especially nematodes detected, it is stressed Acanthocheilonema sabanicolae , a small worm, which implants itself under the skin. The savannah armadillo is also a carrier of Mycobacterium leprae , which can cause leprosy in humans, but the risk of transmission is possibly rather low. The same applies to Trypanosoma cruzi as the cause of Chagas disease , which is common in South America and has also been detected in the savannah armadillo.

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of the armadillos according to Gibb et al. 2015

|

The savannah armadillo is one of seven recent species from the genus of long-nosed armadillos ( Dasypus ). The long-nosed armadillos are in turn integrated into the group of armadillos (Dasypoda) and form a family of their own , the Dasypodidae . The now extinct genera Stegotherium and Propraopus are also counted among these, the former being largely known from the Miocene and comprising several species, while the latter, on the other hand, originates from the Pleistocene and also appeared with several species. According to molecular genetic studies, the Dasypodidae separated from the line of other armadillos in the Middle Eocene around 45 million years ago. With the family of the Chlamyphoridae, this includes all other armadillo representatives today.

Together with the Yungas armadillo ( Dasypus mazzai ), the savanna armadillo forms a more closely related group, but according to a molecular genetic study from 2018, both could also form a common species that consists of two clearly separated populations and then called Dasypus mazzai is run. On the other hand, anatomical analyzes from the same year see the savannah armadillo as independent. A common clade from the nine- banded armadillo ( Dasypus novemcinctus ) and the furry armadillo ( Dasypus pilosus ) faces the two armadillo representatives . Originally it was assumed that the seven -banded ( Dasypus septemcinctus ) and the southern seven -banded ( Dasypus hybridus ) are more closely related to the savannah armadillo, some researchers also believed that all three species should be combined into one, the three then regional would contain differently distributed subspecies. According to genetic studies from 2015, the two seven-banded armadillos are a little further outside. With the exception of the fur armadillo, all of the species mentioned belong to the Dasypus subgenus . The Kappler armadillo ( Dasypus kappleri ), on the other hand, is placed in its own subgenus called Hyperoambon , as is the fur armadillo with Cryptophractus . The greater diversification of the Dasypus subgenus began around 5 million years ago in the transition from the Miocene to the Pliocene .

Fossil evidence of the savannah armadillo comes from the Mene de Inciarte bitumen mine in Venezuela and is between 25,000 and 28,000 years old, i.e. it belongs to the late Pleistocene . However, they only cover a few segments of the solid armor. At the same time, there are also remains of other extinct armadillo representatives, such as Propraopus or Pampatherium from the closely related family Pampatheriidae and the gigantic Glyptodon from the Glyptodontidae family .

The first scientific description of the savannah armadillo was in 1968 by Edgardo Mondolfi . He had eleven individuals available for this. Mondolfi gave the region near Achaguas in the Venezuelan state of Apure as the type locality . Attention for the first time on a new belt species scientists were on a visit to various farms in the region of Río Cunaviche and Río Capanaparo in February 1953 where a copy could be captured.

Threat and protection

The savannah armadillo is heavily hunted locally and used as a food resource. In addition, there is a threat to the population due to habitat destruction. The IUCN classifies the armadillo as “not endangered” ( least concern ), but it is unknown in which direction the population size is developing. In Venezuela, the savannah armadillo can be found in several protected areas. It is also partly kept as a laboratory animal.

literature

- CM McDonough and WJ Laughry: Dasypodidae (Long-nosed armadillos). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2018, pp. 30–47 (p. 45) ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Mariella Superina: Biology and keeping of armadillos (Dasypodidae). University of Zurich, 2000, pp. 1–248

- ^ Brian Keith McNab: An analysis of the factors that influence the level and scaling of mammalian BMR. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part A 151, 2008, pp. 5-28

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Edgardo Mondolfi: Descripción de un nuevo armadillo del género Dasypus de Venezuela (Mammalia - Edentata). Memoria de la Sociedad de Ciencias Naturales La Salle 78, 1968, pp. 149-167

- ↑ a b c d e C. M. McDonough and WJ Laughry: Dasypodidae (Long-nosed armadillos). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2018, pp. 30–47 (p. 45) ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4

- ↑ edentate Specialist Group: The 2004 Edentata species assessment workshop, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, December 16-17, 2004. Edentata 5, 2004, pp 3-26

- ↑ a b c Mariella Superina and Agustín M. Abba: Dasypus sabanicola. Edentata 11 (2), 2010, p. 164

- ↑ James N. Layne: Above-ground nests of the nine-banded armadillo in Florida. Florida Field Naturalist 12, 1984, pp. 58-61

- ↑ Kent H. Redford: Dietary specialization and variation in two mammalian myrmecophages (variation in mammalian myrmecophagy). Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 59, 1986, pp. 201-208

- ^ A b Mauricio Barreto, Pablo Barreto and Antonio D'Alessandro: Colombian Armadillos: Stomach Contents and Infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Journal of Mammalogy 66 (1), 1985) pp. 188-193

- ↑ AA Guglielmone, A. Estrada-Peña, CA Luciani, AJ Mangold and JE Kerans: Hosts and distribution of Amblyomma auricularium (Conil 1878) and Amblyomma pseudoconcolor Aragão, 1908 (Acari: Ixodidae). Experimental and Applied Acarology 29, 2003, pp. 131-139

- ↑ Mark L. Eberhard and I. Campo-Aasen: Acanthocheilonema sabanicolae n. Sp. (Filarioidea: Onchocercidae) from the Savanna armadillo (Dasypus sabanicola) in Venezuela, with Comments on the Genus acanthocheilonema. The Journal of Parasitology 72 (2), 1986, pp. 245-248

- ↑ a b c d Gillian C. Gibb, Fabien L. Condamine, Melanie Kuch, Jacob Enk, Nadia Moraes-Barros, Mariella Superina, Hendrik N. Poinar and Frédéric Delsuc: Shotgun Mitogenomics Provides a Reference Phylogenetic Framework and Timescale for Living Xenarthrans. Molecular Biology and Evolution 33 (3), 2015, pp. 621-642

- ↑ Timothy J. Gaudin and John R. Wible: The phylogeny of living and extinct armadillos (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Cingulata): a craniodental analysis. In: Matthew T. Carrano, Timothy J. Gaudin, Richard W. Blob, and John R. Wible (Eds.): Amniote Paleobiology: Phylogenetic and Functional Perspectives on the Evolution of Mammals, Birds and Reptiles. Chicago 2006, University of Chicago Press, pp. 153-198

- ↑ Laureano Raúl González Ruiz and Gustavo Juan Scillato-Yané: A new Stegotheriini (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) from the “Notohippidian” (early Miocene) of Patagonia, Argentina. New Yearbook for Geology and Paleontology, Abhandlungen 252 (1), 2009, pp. 81–90

- ↑ a b Ascanio D. Rincón, Richard S. White and H. Gregory Mcdonald: Late Pleistocene Cingulates (Mammalia: Xenarthra) from Mene De Inciarte Tar Pits, Sierra De Perijá, Western Venezuela. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (1), 2008, pp. 197-207

- ↑ Maren Möller-Krull, Frédéric Delsuc, Gennady Churakov, Claudia Marker, Mariella Superina, Jürgen Brosius, Emmanuel JP Douzery and Jürgen Schmitz: Retroposed Elements and Their Flanking Regions Resolve the Evolutionary History of Xenarthran Mammals (Armadillos, Anteaters and Sloths). Molecular Biology and Evolution 24, 2007, pp. 2573-2582

- ↑ Frederic Delsuc, Mariella Superina, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emmanuel JP Douzery and Alexandre Hassanin: Molecular phylogenetics unveils the ancient evolutionary origins of the enigmatic fairy armadillos. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 62, 2012, pp. 673-680

- ↑ Agustín M. Abba, Guillermo H. Cassini, Juan I. Túnez and Sergio F. Vizcaíno: The enigma of the Yepes' armadillo: Dasypus mazzai, D. novemcinctus or D. yepesi? Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, NS 20 (1), 2018, pp. 83-90

- ↑ Anderson Feijó, Bruce D. Patterson and Pedro Cordeiro-Estrela: Taxonomic revision of the long-nosed armadillos, Genus Dasypus Linnaeus, 1758 (Mammalia, Cingulata). PLoS ONE 13 (4), 2018, p. E0195084 doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0195084

- ↑ Sergio F. Vizcaíno: Identificación específica de las mulitas, género Dasypus L. (Mammalia, Dasypodidae), del noroeste argentino. Descripción de una nueva especie. Mastozoologia Neotropical 2 (1), 1995, pp. 5-13

- ↑ Mariella Superina and Agustín M. Abba: Dasypus sabanicola. In: IUCN 2012: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. ( [1] ), last accessed on March 22, 2013

Web links

- Dasypus sabanicola in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2013. Posted by: Superina & Abba, 2006. Accessed March 22, 2013.