Kappler armadillo

| Kappler armadillo | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

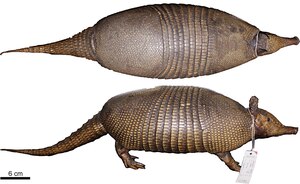

Kappler armadillo ( Dasypus kappleri ), lectotype specimen |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Dasypus kappleri | ||||||||||||

| Krauss , 1862 |

The Kappler armadillo , also known as the Kappler soft armadillo ( Dasypus kappleri ), is the largest species of long-nosed armadillos and the second largest representative of the armadillos with a body weight of around 10 kg . It is mainly found in the Amazon and Orinocos basins in northern South America . There, the armadillo lives predominantly in tropical rainforests and feeds on insects , mostly beetles . The way of life is otherwise little explored. The species was first described in 1862, and according to recent studies from 2016 it may represent a species complex . The population is not considered endangered.

features

Habitus

The Kappler armadillo is the largest type of long-nosed armadillo and is only surpassed by the giant armadillo ( Priodontes maximus ). On the basis of 53 examined individuals from French Guiana , the head-trunk length is 50 to 64 cm and the tail length 29 to 48 cm. The tail corresponds to around 75 to 79% of the body length. The shoulder height is 26 to 32.5 cm, the weight varies from 7.2 to 13 kg. The head is elongated and has a trapezoidal shield on the forehead, formed from irregularly shaped bone plates. The ears reach about 2.8 to 7.5 cm in length and are relatively wide in the middle and slightly pointed at the top. The high armor on the back consists of a solid shoulder and pelvis, both of which are made up of several rows of bone shields with rounded ornamentation about 0.8 cm in diameter. The last row of the shoulder armor can have up to 73 labels. Between these there are seven to nine, often eight movable ligaments made of triangular-patterned bone platelets 0.6 to 0.7 cm wide and 0.8 to 1.2 cm long, connected by skin flaps, with the middle (fourth) ligament consisting of 51 up to 62, an average of 55 of these platelets is built up. Furthermore, up to 15 ring-shaped bone formations can be found on the long tail, which is very broad at the base, of which the front have keeled bone platelets. The belly is also covered by bone platelets, but these are not as densely distributed. In addition, there is a thin coat of hair. The armor is mostly uniformly gray or brownish-gray in color, sometimes the back side is darker, while the side surfaces appear yellowish lighter. The legs are short and end in five rays at the back and four at the front. In contrast to the other long-nosed armadillos, however, a rudimentary fifth ray is formed on the front feet. All toes have strong claws, those of the forefoot are the most pronounced and reach up to 3.2 cm in length. As a special feature of the Kappler armadillo, there are two rows of bone plates on the front of the lower legs, which are 1.7 cm long and protrude freely at the lower end like claws. The rear foot length is 7.8 to 14.8 cm.

Skeletal features

The skull is 11.2 to 13.5 cm long and has a clearly extended rostrum . This takes up about 62 to 67% of the total length of the skull, which is significantly more than in other long-nosed armadillos with the exception of the furry armadillo . The zygomatic arches protrude up to 5.4 cm apart. The teeth do not resemble those of today's mammals, but represent molar-like tooth formations without tooth enamel . Of these, the Kappler armadillo has seven to eight in each upper and seven to nine in each lower jaw arch, a total of 28 to 34. The ulna has a lower front leg has a very large upper joint called the olecranon . With a total length of the bone of 9.3 cm, this becomes a good 3.7 cm long. Such large joint formations on the lower front limbs are typical of animals with a burrowing way of life.

distribution and habitat

The distribution area includes northern South America east of the Andes and extends from the lowlands of the Amazon region in the east from Peru and Ecuador to Brazil . In the north it occurs from Colombia via Venezuela to French Guiana . The eastern border is found around the Rio Araguaia in northern Brazil, but there is still a small separate population on the Amazon island of Marajó and south of it. The Brazilian state of Mato Grosso and northern Bolivia form the southernmost distribution area. The total extent of the occurrence is 5.5 million square kilometers, the actual inhabited area and the density of the population is unknown. The habitat of the Kappler armadillo is the tropical rainforests of the Amazon and Orinoco basins. In the savannah areas of the Llanos , it is only found in more densely wooded areas. The height distribution extends from 120 to 1250 m. In general, the population density is rather low and is given as 0.1 to 0.3 individuals per square kilometer. Only for the Brazilian state of Pará are documented values of 8 individuals on a comparably large area. The armadillo occurs sympatricly with the nine-banded armadillo ( Dasypus novemcinctus ), but may be rarer. The distribution also overlaps with the giant armadillo ( Priodontes maximus ).

Way of life

Territorial behavior

The way of life of the Kappler armadillo has hardly been researched. It lives largely as a nocturnal loner and digs underground burrows in the mostly moist soil of the rainforests. Especially in the only slightly flooded terra firme forests of the Amazon basin, these are mostly laid out on slight slopes and are often found in well-drained soils near the river. The burrows usually have two entrances, which are about 25 cm wide and 14 cm high, but there are only a few differences to the burrows of other armadillo species in this region. Sometimes an animal also occupies abandoned burrows of the giant armadillo . In the chamber under construction there is a nest made of plant material, which consists mainly of leaves and pseudo-trunks. In one observed case in the Llanos region of Colombia, an animal transported up to 25 parts of plants into the burrow over a period of around 80 minutes, the material being clamped between its front legs and stomach. With the protruding claw-like bone platelets on the hind legs, an animal can claw into the burrows in case of danger. Occasionally, the Kappler armadillo bathes in mud holes that were previously used by umbilical pigs .

nutrition

In terms of diet, the Kappler armadillo is an opportunistic insect eater. Studies of the stomach contents of four animals from central Venezuela showed a predominance of beetles , which made up 42.1%. Among these, representatives of the scarab beetles were consumed particularly frequently. Other captured insects represented hair gnats , earth bugs and singing cicadas , while other invertebrates were indicated by spiders as well as double and centipedes . Inorganic material alone accounted for around 15%, which either serves to supplement minerals or was ingested by chance. Ants and termites , on the other hand, played a minor role with a share of 0.8%; members of the genera Pheidole , Atta and Cheliomyrmex could be identified . The analysis of the stomach contents of an individual from Colombia showed a similarly broad picture. Beetles, earth bugs and millipedes predominated here . Ants and termites together made up about a third of the diet. The high proportion of remains of sneak amphibians at around 14% was striking .

Reproduction

Little is known about reproduction, a female usually gives birth to two young per litter. According to three embryo pairs from Venezuela examined, the twins are of the same sex. The births usually take place in the dry season.

Predators and parasites

There are no observations on predators . Animals in danger give off a pungent, musky odor. Ticks of the genus Amblyomma have largely been identified as external parasites , and predatory bugs have also been observed in the Kappler armadillo . Internal parasite reports refer to Babesia and Trypanosoma .

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of the armadillos according to Gibb et al. 2015

|

The Kappler armadillo is a species from the genus of the long-nosed armadillos ( Dasypus ), which includes six other members. The long-nosed armadillos are in turn included in the group of armadillos (Dasypoda). Within this, the genus Dasypus belongs to its own family , the Dasypodidae . Numerous extinct genera such as Stegotherium and Propraopus are also classified in the Dasypodidae . The former is proven from the Miocene and comprised several species, the latter comes from the Pleistocene and also occurred with several species. According to molecular genetic studies, the Dasypodidae separated in the Middle Eocene around 45 million years ago from the line of other armadillos, which are included in the Chlamyphoridae family . It is unclear when the genus Dasypus first appeared. According to genetic studies, the Kappler armadillo separated from the common lineage with the other long-nosed armadillos in the Upper Miocene around 12 million years ago.

The descriptions of Hermann Burmeister from the years 1848 and 1854, in which he presented an armadillo form from Guyana and clearly stood out from the nine-banded armadillo , which was known at the time, are considered to be early mentions of the Kappler armadillo . The scientific name used, Dasypus peba , is invalid, as it was previously used by Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest for the nine-banded armadillo. The first scientific description recognized today therefore goes back to Christian Ferdinand Friedrich von Krauss from 1862. Krauss had four animal specimens and skulls from the natural history cabinet in Stuttgart and from the Zoological Museum in Tübingen . The specimens from the natural history cabinet were made available to him by August Kappler from Surinam , a German soldier and naturalist, whom Krauss named the kappleri species in honor of . The genus name Dasypus was introduced by Linnaeus in 1758 , who he translated from the Aztec word Azotochtli into the Greek language . The word means something like "turtle hare" and is passed down from the Spanish Conquistador Francisco Hernández de Córdoba as the name for the nine-banded armadillo. The name refers to the appearance of the animal. In 1864, Wilhelm Peters described the Kappler armadillo again under the name Dasypus pentadactylus based on a specimen from Guyana and independently of Krauss.In the same report, however, he referred his new species to the genus Hyperoambon, which was also renamed due to the different shape of the palatine bone . The species name is now regarded as a synonymous name for Dasypus kappleri , and hyperoambon is also a sub-genus name for the Kappler armadillo.

As a rule, two subspecies of the Kappler armadillo are distinguished:

The subspecies D. k. pastasae was introduced in 1901 by Oldfield Thomas on the basis of an individual from the upper reaches of the Río Pastaza in Ecuador under the name Tatu pastasae . It is slightly smaller than the nominate form D. k. kappleri . Thomas compared his species with the Kappler armadillo, which he found to be very similar, but highlighted individual skull morphological differences as well as deviations in the shape of the bone platelets on the shell. These show an irregular shape on the pool shield and have a roughened surface. In addition, the osteoderms of the front armor rings are rather flattened. Another form comes from Einar Lönnberg , who in 1942 D. k. beniensis citing a female animal with a total length of 95 cm from the confluence of the Río Madre de Dios with the Río Beni . This is larger than the nominate form, but is similar to D. k. pastasae , which Lönnberg had already moved to the subspecies status of the Kappler armadillo in 1928.

A morphological study published in 2016 on 70 individuals from the entire range of the Kappler armadillo came to the conclusion that these two forms represent separate species, whereby the Kappler armadillo should be viewed as a species complex consisting of three species. According to this view, Dasypus kappleri is limited to northern Brazil north of the lower Amazon and the region from French Guiana to eastern Venezuela . The distribution area of Dasypus pastasae extends along the foot of the Andes in eastern Peru and Ecuador and extends into western Brazil between Rio Madeira and Rio Branco as well as Venezuela. Here it overlaps in the east with the occurrence of Dasypus kappleri . In contrast, Dasypus beniensis occurs in Brazil south of the lower reaches of the Amazon and in Bolivia. An extensive skeletal anatomical study from 2018 repeated this view, but it has so far been rejected by a larger number of researchers due to a lack of genetic studies.

Tribal history

Fossil finds, which include some armor remains and, due to their robustness, can correspond to the Kappler armadillo, are known from the late Pleistocene and come from the Arroio Chuí near Santa Vitória do Palmar in southern Brazil. Today, this find region does not belong to the range of the armadillo species. In addition, a closely related, now extinct representative appeared around the same time as Dasypus punctatus , which has also been detected in today's Brazil.

Threat and protection

No major threats to the species population are known. The Kappler armadillo is mainly hunted as a food resource in Ecuador and Brazil, but the hunting pressure that this creates is not very high. A study that ran from 1993 to 1994 showed that among others the Waimiri Atroari ethnic group of the central Amazon lowlands, which comprised around 800 people at the time, killed a total of 52 long-nosed armadillos, including 44 Kappler armadillos, within this period. The total weight of the armadillos hunted was 452 kg (including 440 kg from the Kappler armadillo), which made up around 1% of the total biomass hunted over the year. A study of individual ethnic groups in French Guiana comes to similar results. The destruction of the rainforests has a stronger and significantly more negative effect on the population of the armadillo. Occasionally, individual animals are also killed in traffic accidents. Due to the wide distribution of the species, the IUCN lists the population as "not endangered" ( least concern ). The Kappler armadillo is represented in several nature reserves, including the large Guiana National Park .

literature

- Carlos Aya-Cuero, Julio Chacón-Pacheco and Teresa Cristina S. Anacleto: Dasypus kappleri (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammalian Species 51 (977), 2019, pp. 51-60

- CM McDonough and WJ Laughry: Dasypodidae (Long-nosed armadillos). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2018, pp. 30–47 (p. 45) ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b C. Richard-Hansen, J.-C. Vié, N. Vidal and J. Kéravec: Body measurements on 40 species of mammals from French Guiana. Journal of Zoology 247, 1999, pp. 419-428

- ^ Edgardo Mondolfi: Descripción de un nuevo armadillo del género Dasypus de Venezuela (Mammalia - Edentata). Memoria de la Sociedad de Ciencias Naturales La Salle 78, 1968, pp. 149-167

- ^ A b Robert S. Voss, Darrin P. Lunde and Nancy B. Simmons: The mammals of Paracou, French Guiana: A neotropical lowland rainforest fauna part 2. Nonvolant Species. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 263, 2001, pp. 3–236 (p. 65)

- ↑ a b c d e f C. M. McDonough and WJ Laughry: Dasypodidae (Long-nosed armadillos). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2018, pp. 30–47 (p. 45) ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Carlos Aya-Cuero, Julio Chacón-Pacheco and Teresa Cristina S. Anacleto: Dasypus kappleri (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammalian Species 51 (977), 2019, pp. 51-60

- ↑ a b c Mariella Superina: Biology and keeping of armadillos (Dasypodidae). University of Zurich, 2000, pp. 1–248

- ^ SF Vizcaíno and N. Milne: Structure and function in armadillo limbs (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Dasypodidae). Journal of Zoology 257, 2002, pp. 117-127

- ↑ Agustín M. Abba and Mariella Superina: Dasypus kappleri. Edentata 11 (2), 2010, p. 158

- ↑ edentate Specialist Group: The 2004 Edentata species assessment workshop, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, December 16-17, 2004. Edentata 5, 2004, pp 3-26

- ↑ a b François Catzeflis and Benoit deThoisy: Xenarthrans in French Guiana: a letter overview of Their distribution and conservation status. Edentata 13, 2012, pp. 29-37

- ^ Eduardo Martins Venticinque and Maria Clara Arteaga: Cuevas de Armadillos (Cingulata: Dasypodidae) en la Central Amazon: Son Útiles para Identificar Especies? Edentata 11 (1), 2010, pp. 29-33

- ↑ Maria Clara Arteaga and Eduardo Martins Venticinque: Influence of topography on the location and density of armadillo burrows (Dasypodidae: Xenarthra) in the central Amazon, Brazil. Mammalian Biology 73, 2008, pp. 262-266

- ^ Carlos Aya-Cuero: Transporte de material vegetal por el armadillo espuelón Dasypus kappleri Krauss, 1862 para la construcción de nido en un bosque de galería de los Llanos Orientales de Colombia. Edentata 17, 2016, pp. 57-60

- ↑ E. Széplaki, J. Ochoa and J. Clavijo: Stomach contents of the greater long-nosed armadillo (Dasypus kappleri) in Venezuela. Mammalia 52 (3), 1988, pp. 422-425

- ^ Mauricio Barreto, Pablo Barreto and Antonio D'Alessandro: Colombian Armadillos: Stomach Contents and Infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Journal of Mammalogy 66 (1), 1985, pp. 188-193

- ↑ Kent H. Redford: Dietary specialization and variation in two mammalian myrmecophages (variation in mammalian myrmecophagy). Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 59, 1986, pp. 201-208

- ↑ David W. Fleck and Robert S. Voss: Indigenous knowledge about the greater long-nosed armadillo, Dasypus kappleri (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae), in northeastern Peru. Edentata 17, 2016, pp. 1-7

- ↑ a b Gillian C. Gibb, Fabien L. Condamine, Melanie Kuch, Jacob Enk, Nadia Moraes-Barros, Mariella Superina, Hendrik N. Poinar and Frédéric Delsuc: Shotgun Mitogenomics Provides a Reference Phylogenetic Framework and Timescale for Living Xenarthrans. Molecular Biology and Evolution 33 (3), 2015, pp. 621-642

- ↑ Timothy J. Gaudin and John R. Wible: The phylogeny of living and extinct armadillos (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Cingulata): a craniodental analysis. In: Matthew T. Carrano, Timothy J. Gaudin, Richard W. Blob, and John R. Wible (Eds.): Amniote Paleobiology: Phylogenetic and Functional Perspectives on the Evolution of Mammals, Birds and Reptiles. Chicago 2006, University of Chicago Press, pp. 153-198

- ↑ Laureano Raúl González Ruiz and Gustavo Juan Scillato-Yané: A new Stegotheriini (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) from the “Notohippidian” (early Miocene) of Patagonia, Argentina. New Yearbook for Geology and Paleontology, Abhandlungen 252 (1), 2009, pp. 81–90

- ^ Ascanio D. Rincón, Richard S. White, and H. Gregory Mcdonald: Late Pleistocene Cingulates (Mammalia: Xenarthra) from Mene De Inciarte Tar Pits, Sierra De Perijá, Western Venezuela. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (1), 2008, pp. 197-207

- ↑ Frederic Delsuc, Mariella Superina, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emmanuel JP Douzery and Alexandre Hassanin: Molecular phylogenetics unveils the ancient evolutionary origins of the enigmatic fairy armadillos. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 62, 2012, pp. 673-680

- ↑ Hermann Burmeister: About Dasypus novemcinctus. Zeitung fur Zoologie, Zootomie und Palaeozoologie 1, 1848, p. 199 ( [1] )

- ↑ Hermann Burmeister: Systematic overview of the animals of Brazil, which were collected or observed during a trip through the provinces of Rio de Janeiro and Minas Geraës. First part. Mammals (Mammalia) Berlin, 1854, pp. 1–341 (p. 301) ( [2] )

- ^ Friedrich von Krauss: About a new belt animal from Surinam. Archive for Natural History 28 (1), 1862, pp. 19–34 ( [3] )

- ↑ Wilhelm Peters: About new kinds of the mammal genera Geomys, Haplodon and Dasypus. Monthly reports of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin 1864 (1865), pp. 177–181 ( [4] )

- ↑ a b Anderson Feijó and Pedro Cordeiro-Estrela: Taxonomic revision of the Dasypus kappleri complex, with revalidations of Dasypus pastasae (Thomas, 1901) and Dasypus beniensis Lönnberg, 1942 (Cingulata, Dasypodidae). Zootaxa 4170 (2), 2016, pp. 271–297 ( [5] )

- ↑ a b Anderson Feijó, Bruce D. Patterson and Pedro Cordeiro-Estrela: Taxonomic revision of the long-nosed armadillos, Genus Dasypus Linnaeus, 1758 (Mammalia, Cingulata). PLoS ONE 13 (4), 2018, p. E0195084 doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0195084

- ^ Alfred L. Gardner: Order Cingulata. In: Don E. Wilson and DeeAnn E. Reeder (Eds.): Mammal Species of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, pp. 94-99 ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0 ( [6] )

- ↑ Oldfield Thomas: New species of Saccopteryx, Sciurus, Rhipidomys, and Tatufrom South America. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 7, 1901, pp. 366–371 ( [7] )

- ^ Einar Lönnberg: Notes on Xenarthra from Brazil and Bolivia. Arkiv för Zoologi 34 (9), 1942, pp. 1-58

- ↑ Édison V. Oliviera and Jamil C. Pereira: Intertropical Cingulates (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Quaternary of southern Brazil: Systematics and paleobiogeographical aspects. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 12 (3), 2009, pp. 167-178

- ↑ Mariela C. Castro, Ana Maria Ribeiro, Jorge Ferigolo and Max C. Langer: Redescription of Dasypus punctatus Lund, 1840 and considerations on the genus Propraopus Ameghino, 1881 (Xenarthra, Cingulata). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33 (2), 2013, pp. 434-447

- Jump up ↑ Roselis Remor de Souza-Mazurek, Temehe Pedrinho, Xinymy Feliciano, Waraié Hilário, Sanapyty Gerôncio and Ewepe Marcelo: Subsistence hunting among the Waimiri Atroari Indians in central Amazonia, Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation 9, 2000, pp. 579-596

- ↑ Agustín M. Abba and Mariella Superina: Dasypus kappleri. In: IUCN 2012: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. ( [8] ). At www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

Web links

- Dasypus kappleri in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2013. Posted by: Abba & Superina, 2006. Accessed March 6, 2013.