Singing cicadas

| Singing cicadas | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Cicadidae | ||||||||||||

| Latreille , 1802 |

Singing cicadas (Cicadidae) are a family within the suborder of the round-headed cicadas (Cicadomorpha). The insects are able to produce audible sounds for humans. For this they have specially trained drum organs ( tymbals ). The German name refers to their species-specific and therefore determinative chants.

The representatives of this family are among the best-known cicadas because of their song, their often conspicuous coloring and their size. For example, the Indomalayan Imperial Cicada ( Pomponia imperatoria ) reaches 11 centimeters in length and has a wingspan of over 22 centimeters. Names such as “Black Prince”, “Cherry Nose”, “Roach” or “Green Merchant” give an impression of the striking coloring of Australian singing cicadas.

Morphological features

The color of the cicadas is usually so well adapted to the environment that laypeople can hardly recognize them in the vegetation . The animals are one or more colored. Earth tones such as brown, black, green, yellow and orange tones predominate. The build of the singing cicadas is usually stocky. While the males of the imperial cicada ( Pomponia imperatoria ) can reach body lengths of up to 11 centimeters and wingspan of over 22 centimeters, the smallest known singing cicada, Panka parvulina , measures only 1.4 centimeters with a wingspan of about 2.4 centimeters. The females have a more or less long ovipositor , which makes the abdomen appear pointed. The abdomen of the males is bluntly rounded and tinted differently depending on the species.

The pronotum is stocky and short. It covers less than half of the mid-chest ( mesothorax ). The head is big. The adult animals have complex eyes ( compound eyes ) that are clearly bulging to the side . They have three point eyes ( ocelli ), which are arranged in a triangle on the forehead ( frons ). This feature distinguishes them from all other species of cicada that have only two ocelli or whose pointy eyes are completely regressed. The clearly articulated antennae that set in between the eyes are very short. They each consist of two thick base links and a five-link, slim antenna bristle. The bubble-like bulging head shield, which is characterized by several transverse grooves and folds, is striking. The proboscis ( rostrum ) arises at the lower edge of the face and , when at rest, lies folded against the body between the hips ( coxa ).

The front wings are folded roof-like at rest in more characteristic of cicadas way. They always protrude beyond the abdomen . The well-developed and well-developed veining of the hyaline , completely, partially or not at all pigmented forewings is different in color depending on the species. Parts of the veins are colored differently and, together with the different architecture of the veins, form a species-differentiator. The wings are surrounded by a vein-free space. Under the forewings are the smaller, more simply shaped, membranous hindwings. They are linked to each other in flight by ticks on the leading edge of the rear wing.

The thighs ( femora ) of the front legs of adult animals are, in contrast to the normally shaped middle and rear legs, clearly thickened and thorny. The front legs of the larvae have developed into grave legs in adaptation to their underground way of life. Singing cicadas have no jumping ability like other representatives of the round-headed cicadas.

The males have a drum organ ( tymbal ) on the sides of the first abdominal segment , behind the attachment of the hind wings. By attaching muscles (sing muscles), outwardly curved records reinforced by ribs are made to vibrate. These are exposed (Tibicininae) or are covered by a sound cover (Cicadinae) extending from the second back plate of the exoskeleton ( Tergite ). The noise is created by indenting (muscle pull) and jumping back (inherent elasticity). Directly under the sing muscle, a large air sac in the hollow abdomen provides the necessary resonance . With the help of these organs, sounds of up to 900 Hertz and volumes of up to 120 dB can be generated. On the underside of the abdomen of both sexes are auditory organs ( tympanals ). The paired organs consist of a wafer-thin membrane that absorbs vibrations. In addition to the special drum organs, some members of the family have other stridulation organs, in which two parts are rubbed together and produce sound.

Nutrition and breathing

All leafhoppers are xylem suckers . With the help of their proboscis, the adult animals prick the pathways of various woody plants and herbaceous plants and suck the sap rich in nutrients and water . The subterranean larvae suck the sap from plant roots.

The internal anatomy and physiology of the singing cicadas largely correspond to that of the insects. In adaptation to the special diet, singlethoppers like all round-headed leafhoppers have a special construction of the digestive tract in order to release excess water or carbohydrates . The very water-rich plant sap of the conduction pathways (xylem) is, in contrast to the sugar-rich phloem sap, significantly poorer in nutrients, which is why the leafhoppers, which only feed on it, have to ingest a lot of them. There is a filter chamber in the intestine of the sap suckers, which creates a transition region between the fore and midgut and the hindgut. It allows the excess water to be drained directly into the rectum and the nutritional juice is thickened before it enters the midgut. Furthermore, the centers of the rope ladder nerve systems typical of insects are only present in the round-headed cicadas in the head and chest; the abdomen is supplied by the nerve center of the chest.

In almost all insects, breathing also takes place via the tracheal system . However, special structures are evidently developed in the larvae of the last stage of development (L5) of some African species of singing cicadas that have changed to life in liquid (e.g. Muansa clypealis , Ugada limbalis , Orapa elliotti ). With them, the abdomen is redesigned for breathing and holding on. The abdomen is equipped with a liquid-repellent surface. There is a layer of air on the surface of the body, which is renewed every now and then when the abdomen is stretched out of the fluid. Apparently the liquid is not groundwater or rainwater, but rather the water-rich excretions of the larva itself, which collect in the soil with colloidal properties and cannot seep away .

Sound generation

The typical song of the singing cicadas, known to some from a vacation in the Mediterranean , is similar to that of grasshoppers or crickets , but is produced differently. While these stridulate , the male singing cicadas have tymbal organs ("drum organs"), left and right at the base of the abdomen. The tymbal organs each have a curved sound membrane, which is set in vibration by the rhythmic contraction of a muscle, thereby producing the sound.

Although all species of cicada emit sound or vibration waves for communication, only the majority of the representatives of the Cicadidae are able to produce audible sounds for humans. The singing of the males serves primarily to attract the females, but it is also used to establish territorial boundaries . There are also known protest and alarm sounds when touched. It is not yet clear why the males sing almost continuously during the day or at dusk. Some also add wing click signals to their singing. The females are mostly mute. However, those of some species are able to send a short click-like “yes”, which is created by special wing beats, in the mating behavior.

Most species produce sounds in the range clearly audible to humans. Some species, on the other hand, produce a frequency range at the upper hearing limit of a young healthy person. The chants are species-specific and can be described using oscillograms and sonograms . They can be used for species identification.

Reproduction, Development and Life Cycle

The females attracted by the chants fly to the singing males. With the other species of round-headed leafhoppers, the reverse is the rule. The females are usually stationary there. To mate, the animals often gather in large numbers in trees, bushes or in the lower vegetation. Overall, little is known about advertising and mating behavior.

The copulation is done by the male approaching from the side of the female, his abdomen tip under the push of the female and his penis ( Aedeagus ) from below at the base of the ovipositor ( ovipositor introduced) into a developed only with cicadas this family Kopulationsöffnung. It is believed that the pairing is repeated several times. Then the female looks for thin branches of wood or stems of herbaceous plants in order to lay her oval eggs in holes drilled with her powerful saw. The seventeen-year-old cicada ( Magicicada septendecim ) lays 400 to 600 eggs in the course of a month in this way.

Embryonic development is complete after five to eight weeks . The young larvae burst the egg shell and slip out of the puncture opening, pulling off the embryonic shell. You fall to the earth. From now on the yellowish or whitish larvae live burrowing in the ground. In addition, they have strong forelegs, developed into grave legs, the very short legs ( tibia ) of which are thickened and thorny. The larvae suckle on roots. Once they have found a suitable source of food, they set up a living room. Depending on the soil conditions, the larvae can be found between 15 and 60 centimeters deep. Sometimes they even penetrate up to 3 meters deep into the ground.

Song cicadas are hemimetabolic , which means that they go through five larval stages (L1 to L5) separated by moulting, gradually becoming more and more similar to the adult animal. They have a very long larval development time compared to their adult life, which lasts a few months. In the Cicadidae this lasts from nine months to several years. Usually it is two to five years. The song cicadas of the genus Magicicada , which is common in North America , are even 13 or 17 years old. They are particularly characterized by regular mass multiplication.

Towards the end of development, the larvae work their way towards the surface of the earth. In the final stages, the larvae of a few species create slim, cylindrical, up to 30 centimeter high turrets made of earth, in order to leave them after about three weeks through an exit hole. Some species live in water-filled tubes and are morphologically adapted accordingly (see above). To date, nothing is known about the exact function of these buildings. It is possible that this is the only way to achieve the environmental conditions necessary to complete the development. The larvae, which are ready to hatch, then climb up trees and bushes when the weather is favorable and often at night, cling tightly and after a short time the full insects hatch.

Slip of Lyristes plebejus

distribution

With more than 4000 known species, the warmth-loving singing cicadas are distributed worldwide, but mainly in the tropics and subtropical zones . The largest representatives of this family live in India , southern China and the Great Sunda Islands . In Europe , the singing cicadas occur with 61 species in 12 genera predominantly in the Mediterranean area, with around 13 to 14 species in 7 genera penetrating into regions of Central Europe that are particularly thermally favored , of which three species occur in 3 genera in Germany.

The following species have been found in Germany , Austria and Switzerland :

- Cicada orni (Mannasing cicada) *, Germany, Austria

- Cicadatra atra (Black Cicada) **, Switzerland

- Cicadetta montana ( Mountain Cicada ) *, Germany, Austria, Switzerland

- Cicadetta tibialis (Dwarf Cicada), Austria

- Lyristes plebejus (Great Cicada) **, Austria, Switzerland

- Tibicina haematodes (Weinzwirner) *, Germany, Austria, Switzerland

- Tibicina quadrisignata , Switzerland

German names after * Nickel & Remane 2002, ** Gogala 2002

Phylogeny and systematics of the Cicadidae

Singing cicadas have existed since the Eocene , as evidenced by inclusions (inclusions) in amber .

According to current opinion, the Cicadoidea are next to the Membracoidea and the Cercopoidea a superfamily of the round-headed leafhoppers (Cicadomorpha). A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the superfamily of the Cicadoidea based on the determination of the ribosomal 18S-r DNA , 28S-rDNA and histones 3 confirms the monophyly of the superfamily. It includes the families of the singing cicadas (Cicadidae) and the Tettigarctidae . The latter includes only two species native to south-eastern Australia and Tasmania .

The singing cicadas comprise the subfamilies Cicadinae and Tibicininae, some of which are also regarded as separate families by some authors. The taxonomy and species assignments have not yet been conclusively clarified in this regard. In more recent studies, the subfamilies Cicadinae, Cicadettinae and Tibicininae are distinguished. Many species that previously belonged to the Tibicininae are now placed in the subfamily Cicadettinae and the remaining part of the Tibicininae is then alternatively referred to as Tettigadinae. The very similar subfamily Tibiceninae from America is another subfamily, but today it is mostly seen as part of the Cicadinae.

Mythology, Art and Folklore

Cicadas, and especially the singing cicadas, have been a part of mythology , art and folklore for millennia . Their special meaning results above all from their singing, their extraordinary way of life, their omnipresence, their size and their beauty.

Cicadas in the culture of different peoples

Singing cicadas formed the basis for numerous legends and myths in various peoples . The mythological meaning was limited to several regions in which singing cicadas still occur today. These are ancient Greece , ancient China and Japan, and North America . In Africa and ancient Egypt , the song cicadas seem to have played a role in people's imaginations. They were revered as a symbol for the human soul and viewed as a symbol for immortality, rebirth, a long life, and sometimes also for eroticism.

The ancient Greeks already knew that the chants originated mainly from the males and led the Greek poet Xenarchus to say: " The cicadas live happily because they have mute women ". Because of the never-ending chants, cicadas were a symbol of talkativeness.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) described as early as the 2nd century BC At least in the main the way of life of the singing cicadas. It was believed in Greece at the time that the adult cicadas would not eat any food. In Greece, the first sculptural representations of the animals are known from prehistoric times. In the graves of the city of Mycenae (2000 BC), models of wingless insects, interpreted as cicada larvae, were found. The grave goods indicate the importance of the cicadas as symbols of immortality and a long life. Singing cicadas, as metaphors for the art of singing and eloquence (muses) and immortality, were much more deeply rooted in the minds of the Greeks. According to Phaedrus , a text by the philosopher Plato (429-347 BC), it is assumed that cicadas as ambassadors of the muses were understood to be synonymous with "disembodied souls". They should have freed themselves from the physical needs (= shedding of the larval skin) and thus have reached a higher level of knowledge. Thus cicadas were apparently seen as a "model of the human" soul.

In China there are various representations and ornaments with cicada motifs on objects that date back to around 1500 BC. To date. Evidence of so-called "tongue cicadas" has existed since the Han dynasty (206–220 BC), possibly even before that. The figures carved from jade were placed on the tongue of the deceased in the hope of their rebirth.

The natives of the New World observed the peculiar periodic recurrence of song cicadas (genus Magicicada ) and integrated the phenomenon into their mythology . The Hopi Indians (Oraibi) living in Arizona attributed the power of immortality to the animals. Such supernatural powers were called kachina . These were given away in the form of carved dolls for religious instruction to children. One was called "Mahu" (cicada). She is still worshiped today in dances and ceremonies.

Literature, music and fine arts

In literature (poems, fables and short stories) the cicadas play an important role. The main focus is on the cicadas as singers or symbols for music and art, but also as noise producers.

Singing cicadas and their chants are mentioned in the earliest written works, the " Iliad " by Homer (800 BC). The aspects of the Greek “cicada mythology” are processed in the poem “To the cicada” by Anakreon . It is a probably from the 5th century BC. Chr. Hymn to the "godlike" singing cicadas. The poem also enjoyed great popularity in later times. For example, it was translated by Thomas Moore and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe . In German-speaking countries, the cicadas are mentioned in Heinrich Heine's poems "Die Libelle" ("... And with the Cikade, the artist ...") or in Karl Leberecht Immermann's epic "Tulifäntchen" ("... To the tulip feet played / the sound expert Cicadas / chosen band / pieces by the best masters ... ”). Eugen Roth is not very friendly in his poem “Die Zikaden”: “I give praise to Anakreon / The flute of the cicadas. / But it's too easy at night: O unfortunate flute playing! " Another modern poem that is Dao (2001)", which aims brushing and trimming "on emanating from the chirping of cicadas melancholy mood.

Probably the best known fable is that which goes back to the Greek fable poet Aesop (600 BC). It was published by Sebastian Brant in 1501 in the version "De formica et cicada" and brought into verse form by the French La Fontaine (1621–1695) in 1668 with the title "La Cigale et la Fourmi". Both authors expressly speak of a cicada, while terms such as “grasshopper”, “cricket” or “grasshopper” are used in German and English translations by later authors. Correspondingly, many contemporary illustrations, especially those by the aforementioned authors Brant and La Fontaine, depict crickets or grasshoppers instead of singing cicadas. The reason for this confusion of the cicadas with other "singing" insects is assumed to be that the singing cicadas are mainly native to the Mediterranean area. They were little known to the illustrators, readers and maybe also authors in Central Europe or there was simply no comparable term available. The singing cicadas were therefore consciously or unconsciously replaced by the species better known in Central Europe, since the correct species name does not play a role in the message of the fable, namely to prepare for winter in summer.

The distinctive singing of the insects suggests that they play a bigger role in the music too. However, relatively few pieces of music are known that have cicadas as a motif. The Swiss composer Ulrich Gasser wrote the piece “Die singenden Zikaden” in 1989 for flute and three sound stones. Wassili Leps set a cicada drama "Yo-Nennen" in the form of a cantata . Based on a poem by the Greek Anakreon "An die Zikade" (see above), the German composer Harald Genzmer (1909–2007) composed the piece of the same name.

A particularly large number of examples of songs and poems that have cicadas as their subject are from the south of France. Especially in Provence , singing cicadas are symbolically used as an expression of the light, Mediterranean attitude to life and sung about in folk songs. Examples of cicadas in chansons are “Aussi bien que les cigales” or “La mort de la cigale”. Cicadas have also found their way into modern folk, pop and light music. Linda Ronstadt , for example, sings melancholy about the cicadas in her song "La Cigarra", alluding to their short life.

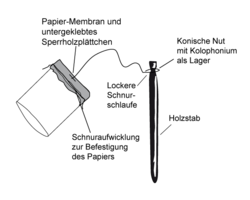

In Asia and southern Europe there is a musical instrument popular with children, which is known as the “cicada” or “toulouhou”. This imitates the chants of singing cicadas or at least creates snarling noises. On a stick with a conical groove coated with rosin runs in the loop of a cord. At the other end of the string a box with a stretched membrane is attached. The instrument is made to sound by spinning around, whereby the cord alternately adheres and slides in the groove through the resin . The noises are transmitted to the membrane via the cord, the can acts as a resonance body.

The oldest pictorial representations come from China and Japan on vessels and tissue paper. Van Gogh, who made several drawings of singing cicadas, should be mentioned above all in modern art. Singing cicadas are also a popular motif among the artists of the Japanese art of folding origami . A singing cicada can be made from a piece of paper with 95 folding steps.

The mascot of the Venezuelan reggaeton band Dame Pa 'Matala is a singing cicada.

Folk art and everyday life

The insects were and are often part of jewelry. In ancient Greece not only coins with cicada motifs were minted, but the citizens of Athens also wore gold jewelry, such as hairpins with ornaments in the shape of a cicada . Later they were considered a symbol of the autonomy of Athens, since the earliest ancestors, like the cicadas, “slipped away” from the traditional soil. With the Goths and the Romans , cicadas were considered symbols of power. They also wore jewelry with cicada motifs as a status symbol. In the Middle Ages , troubadours wore cicada brooches, probably as an expression of their guild.

300 cicada-shaped pieces of jewelry were added to the grave of the first Frankish king Childerich I († 482 AD), or his favorite horse, who was also buried. When the grave was discovered in the 17th century, they were initially mistaken for "bees" and as a trim for the royal mantle, but they were part and decoration of the horse harness. Today it is assumed that these are cicadas and possibly also singing cicadas. Napoleon (1769–1821) was so impressed by the grave goods that, ignorant of their former significance, he had his coronation cloak embroidered with 300 golden "bees".

The singing cicadas are particularly widespread in everyday life in Provence . As an expression of the light Mediterranean attitude to life, one encounters the animals in the Provencal culture in a variety of forms, for example on restaurant signs, as a welcome symbol over front doors, in the form of small clay figures and faience , as representations on vases and crockery or brooches. In many other countries and regions of the world you can find images of singing cicadas on postage stamps and other everyday objects.

Singing cicadas were and are also used in medicine . Larval skins were mainly used in China and Japan to make a remedy, ironically for earache. Even today, cicadas are used to make preparations against fever. In the Orient, the cicada Huechys sanguinea ("red medicinal cicada") was used as a remedy for blisters. Based on the belief that cicadas are immortal, the Oraibi Indians also used a medicine from these animals against fatal injuries.

Cicadas, especially singing cicadas, still play a role in nutrition today. Cicadas have a physiological calorific value of approx. 640 kJ (= 153 kcal ) per 100 g, similar to fried chicken. 73 edible species of cicada are known worldwide, including several species of singing cicada. Among the Tabare Sine, a people who live in the highlands of Papua New Guinea , the singing cicadas that live there are considered a delicacy ( Cosmopsaltria papuensis , Cosmopsaltria aurata , Cosmopsaltria mimica , Cosmopsaltria gigantea gigantea ). The cicadas have names such as "Dui helme" or "Dui meh" in the vernacular. Furthermore, the song cicadas are so deeply rooted in people's everyday life that they direct their activities such as field work and hunting to the times of the day marked by the song of the cicadas. For example, they start preparing for the hunt when the singing of “Dui erangrre” ( C. mimica ) can be heard. When "Dui wave" ( C. gigantea gigantea ) sings, it is time to go into the forest and hunt, as all the other animals are then also active. "Dui wave" roughly means "Cuscus closes the door" and refers to the song of the insect, which sounds like a door closing.

Individual evidence

- ^ MS Molds: Australia Cicadas. - New South Wales University Press 1999, NSW.

- ^ R. Remane & E. Wachmann : Cicadas - get to know, observe - Naturbuch Verlag, Augsburg 1993. ISBN 3-89440-044-7

- ↑ Hans Strümpel: The cicadas . In: New Brehm Library . tape 668 . Westarp Sciences, 2010, ISBN 3-89432-893-2 , pp. 82 ff .

- ↑ a b M. Gogala: Songs of the singing cicadas from Southeast and Central Europe. In: Denisia 4, pp. 241-248, 2002, ISBN 3-85474-077-8

- ↑ Cicadoidea in Fauna Europaea , as of March 2, 2015.

- ^ WE Holzinger: Provisional directory of the cicadas of Central Europe (Insecta: Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha et Cicadomorpha); Preliminary checklist of the Auchenorrhyncha (leafhoppers, planthoppers, froghoppers, treehoppers, cicadas) of Central Europe , Stand 2003 ( [1] ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this note .; PDF; 122 kB), accessed on May 8, 2007

- ↑ a b Herbert Nickel and Reinhard Remane: List of species of cicadas in Germany, with information on nutrient plants, food breadth, life cycle, area and endangerment (Hemiptera, Fulgoromorpha et Cicadomorpha). Contributions to the cicada, 5, pp. 27–64, 2002 full text (PDF, German; 234 kB)

- ^ WE Holzinger, I. Kammerlander & H. Nickel: The Auchenorrhyncha of Central Europe - Die Zikaden Mitteleuropas. Volume 1: Fulgoromorpha, Cicadomorpha excl. Cicadellidae. - Brill, Leiden 2003, ISBN 90-04-12895-6

- ↑ A. & J. Stroinski Szwedo: An overview of Fulgoromorpha and Cicadomorpha in East African copal (Hemiptera). In: Denisia 4, pp. 57-66, 2002, ISBN 3-85474-077-8

- ↑ JR Cryan: Molecular phylogeny of Cicadomorpha (Insecta: Hemiptera: Cicadoidea, Cercopoidea, and Membracoidea): adding evidence to controversy. Systematic Entomology 30 (4), Oct 2005, pp 563-574.

- ↑ a b Roland Achtziger, Ursula Nigmann: Cicadas in Mythology, Art and Folklore. In: Denisia 4, pp. 1-16, 2002, ISBN 3-85474-077-8 . PDF (1.4 MB)

- ↑ E. Kysela: Cicadas as part of jewelry and traditional costumes in the Roman Empire and the Migration Period. In: Denisia 4, pp. 21-28, 2002, ISBN 3-85474-077-8

- ↑ M. Mogia: Traditional uses of cicadas by Tabare Sine people in Simbu province of Papua New Guinea . In: Denisia 4, pp. 17-20, 2002, ISBN 3-85474-077-8