Schaffgotsch-Palais Bad Warmbrunn

The Schaffgotsch-Palais ( Polish : Pałac Schaffgotschów Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój ) in the Polish Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój (Bad Warmbrunn), a district of Jelenia Góra (Hirschberg), is an early classical palace with an extensive palace and spa park.

history

The current palace was built in the years 1784–88, the design dragged on for a long time. The master builder was Johann George Rudolf (1725–1799) from Opole , who also worked for the Grüssau Abbey , builder Count Johann Nepomuk Schaffgotsch .

Warmbrunn first appeared in a document in 1281, when Duke Bernhard von Jauer and Löwenberg gave the Johannitern from Striegau land at the "warm spring". The patronage of the Catholic parish church (St. John the Baptist ) reminds of this to this day. A hundred years later Gotsche II. Schoff, whose father had come into possession of the Kynast Castle , bought the village "with all affiliations ... princely rights and courts".

A castle in Warmbrunn was first built in 1687 on the occasion of a bathing visit by Queen Maria Kasimira of Poland , the wife of Jan III. Sobieski , mentioned. This building was built between 1550 and 1600 and presumably resembled the castle Schwarzbach (Czarne) , which is still preserved today , built in 1559. In both cases , the builders were representatives of the Schaffgotsch family , which had ramified widely by the 16th century.

In the first half of the 17th century, this castle became the central residence of the main Silesian line of Count Schaffgotsch, probably even before the fire of the Kynast in 1675. The comparison between the narrow and inaccessible castle and the castle at the thermal spring just a few steps away at least suggests that, and the order in which the goods were returned after the disaster of Baron Hans Ulrich in 1635 (1638 Greiffenstein , 1649 Kynast ) does not seem to support the news that the cynast was the usual residence of the family. In 1720, Count Hans Anton Schaffgotsch had a building, later called the “Stiegenhaus”, built 50 m east of the “Old Castle” in order to offer family and guests more space. His son Carl Gotthard commissioned a renovation of this building in 1773, which came close to a new building.

The Renaissance castle burned down completely on October 27, 1777 at 10 p.m. as a result of a lightning strike, including the nearby farm buildings. The 80-year-old Count Carl Gotthard and his son Johann Nepomuk decided, as the “staircase” by the “famous master builder” was “so clumsily built and everything was done so unreasonably” to replace both old buildings with a single new one. Count Carl did not see the end of the protracted planning that his son carried out with the construction of the present-day castle, which remained the seat of the main line of the Silesian Schaffgotsch until 1945.

In the palace gardens and the adjoining spa gardens, more buildings were gradually built. South of the palace, Count Johann Nepomuk had Carl Gottfried Geisler (who also built Schloss Milicz (Militsch)) build a classicist society house, the “gallery”, for the spa between 1797 and 1800 . Under Count Leopold Gotthard, orangery and greenhouses followed around 1820, with Carl Anton Mallickh as master builder. In 1836, Count Leopold Christian had a classical theater built by Schinkel's student Albert Tollberg. In 1906 the spa facilities were supplemented by the Volkspark, in which a Norwegian log house was erected.

After the region was incorporated into the People's Republic of Poland , the castle was initially used as a hospital. Furniture and collections of the Schaffgotsch were removed or destroyed. From 1946 it served as a rest home for the State Council, and since 1975 it has housed a branch of the Technical University of Wroclaw .

Building

Today's building partly includes the foundation walls of two previous buildings, about which we are only partially informed.

Previous buildings

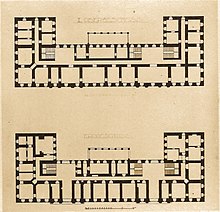

For the 16th century renaissance castle, which burned down in 1777, the foundation walls drawn in the plans for the new building from 1784 show that it was an area of 58 cubits (36.7 m) square around an inner courtyard without arcades. Old city views show a two-storey building with a simple saddle roof and stepped gables, reminiscent of a miniature version of Oels Castle ( brought into its current form by the Dukes of Münsterberg between 1558 and 1617). The north-west corner of today's castle stands on its foundations.

The builder of the “staircase” built in 1720 was probably Elias Scholtz. The order for the renovation of 1773 was given to the master mason Christian Seidel from Hirschberg and the city carpenter Wilhelm Predow. The two-story house had a rectangular floor plan of 58 by 32 cubits (36.7 by 21.3 m), 9 window axes lengthways and 4 across. The three central window axes of the longitudinal front were grouped together with the portal and crowned by a gable that protruded into the lower part of the broken hip roof .

The palace

The three-storey castle rises above a horseshoe-shaped floor plan that opens to the south towards the park. The city front measures 82 m with 21 window axes, the side wings each have 7 window axes with a length of 30 m.

The main facade is structured by two slightly protruding, three-axis risalits with gate entrances. Their windows are oval in shape on the top floor, their pilasters have balustrades with vases and the Schaffgotsch coat of arms in the upturned central fields. Apart from the sparse ornaments on the window frames, the facade surface in between is unadorned and unstructured. The high, gewalmte saddle roof is formed by a series of curly onlookers loosened and 8 coarse chimneys.

The exterior of the building has only seen one change. On the garden side, a glazed arbor on the ground floor was added in the middle part over 6 axes in width .

The interior breathes the same generous sobriety. A long corridor runs through the middle of the entire building on all floors, following the floor plan, which opens up all the rooms and only extends as a stair landing like a hall towards the garden side behind the risalits. Behind the western risalit on the street side is the two-storey ballroom designed in Empire style in 1809 , whose fine stucco ornaments between massive pilasters represent the main industries of the Giant Mountains . The palace chapel changed its place twice and was most recently located on the 2nd floor above the east portal to the north. The altarpiece came here from the chapel of Greiffenstein Castle, which was destroyed in 1799, and showed Christ on the cross.

Until 1945 , the furnishings also included a portrait collection , which, with over 180 portraits, was one of the largest of its kind in Silesia. It mainly contained pictures of members of the owner family and their relatives, but also showed representatives of ruling houses, especially the Silesian Piasts , the Habsburgs , Hohenzollerns and Wettins . The thematic highlight of the gallery was the eastern hall with six life-size Piast portraits. Some of the pictures are now in the National Museum in Wroclaw , some in the National Museum in Warsaw . The vast majority of them are missing.

The substance of the palace was not affected by the structural fashions of the 19th century, if we disregard the addition of the arbor and a larger interior construction in 1865–66. The latter was partially reversed by the last nobleman, Count Friedrich, so that in the first half of the 20th century the castle could be regarded as one of the best-preserved and best-kept art monuments of the late 18th century in Silesia.

There was a baroque palace garden to the south of the palace, which was transformed into an English landscape garden in 1819 .

Current condition

Today the castle has been restored and the interior has been furnished with furniture from other Silesian castles. The palace and spa gardens form a joint ensemble. The Norwegian log cabin houses a natural history museum.

literature

- Günther Grundmann: Silesian architects in the service of the Schaffgotsch rule and the Warmbrunn provost, publication from the Graf Schaffgot archive . In: Studies on German Art History . Issue 274th JH Ed. Heitz, Strasbourg 1904, p. 214 pages and 60 tables .

- Arne Franke (Hrsg.): Small cultural history of the Silesian castles . tape 1 . Bergstadtverlag Wilhelm Gottlieb Korn, 2015, p. 177-178 .

- Heinrich Nentwig: Schoff II. Gotsch called, Fundator . In: Messages from the Reichsgräflich Schaffgotsch archive . III. Notebook. Max Leipelt, Warmbrunn 1904.

- Johannes Kaufmann: The preservation of the Schaffgotsch family estates by Fideicommisse . In: House history and diplomatarium of the Reichs-Semperfrei and Count Schaffgotsch . Volume Two, History of Ownership, Part Two. Leipzig-Bad Warmbrunn 1925.

- KA Müller: The Burg festivals and Ritter locks Silesia (both Antheile), such as the county Glatz . In: Patriotic images in a history and description of the old castle festivals and knight castles of Prussia . First part. Carl Flemming, Glogau 1937.

- Magdalena Palica: The portrait gallery in the Warmbrunn Palais Schaffgotsch . In: Joachim Bahlcke, Ulrich Schmilewski, Thomas Wünsch (eds.): The Schaffgotsch House, Denomination, Politics and Memory of a Silesian Noble Family from the Middle Ages to the Modern Age . Bergstadtverlag Wilhelm Gottlieb Korn, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-87057-297-6 , p. 317-328 .

Web links

- Views of Warmbrunn from around 1600. | https://polska-org.pl/8179659,foto.html?idEntity=529893

Individual evidence

- ^ Heinrich Nentwig, Schoff II. Gotsch called, Fundator, Warmbrunn 1904, p. 12.

- ^ Günther Grundmann, Silesian Architects in the Service of the Schaffgotsch Rulership and the Warmbrunn Provost, Studies on German Art History, Strasbourg 1930, p. 83.

- ↑ Grundmann, p. 83f.

- ↑ See Johannes Gotthelf Luge, Chronik der Stadt Greiffenberg in Schlesien, Greiffenberg 1861, p. 41.

- ↑ See Johannes Kaufmann, The preservation of the Schaffgotsch family estates through Fideicommisse, house history and diplomatarium of the Reichs-Semperfrei and Count Schaffgotsch, second volume: Property history, second part. Leipzig - Bad Warmbrunn, 1925, p. 38.

- ↑ Grundmann, pp. 84f.

- ↑ Count Carl Gotthard in a letter, quoted in n. Grundmann, p. 85.

- ↑ See Grundmann, pp. 142–153.

- ↑ See Grundmann, 154 ff.

- ↑ See Grundmann, 166 ff.

- ↑ See https://polska-org.pl/8179659,foto.html?idEntity=529893 .

- ↑ Grundmann, p. 83f.

- ↑ Grundmann, p. 85 and https://polska-org.pl/6047676,foto.html or https://polska-org.pl/772498,foto.html?idEntity=529893 .

- ↑ See Grundmann, pp. 98f.

- ↑ See Grundmann, p. 115f.

- ↑ Cf. Magdalena Palica, Die Portraitgalerie im Warmbrunn Palais Schaffgotsch, in: Joachim Bahlcke, Ulrich Schmilewski, Thomas Wünsch (eds.), Das Haus Schaffgotsch, Denomination, Politics and Memory of a Silesian Noble Family from the Middle Ages to Modern Times, Würzburg 2010, p 317, 321, 328.

- ↑ See Grundmann 116.

- ↑ See Franke 178.

Coordinates: 50 ° 51 ′ 54 ″ N , 15 ° 40 ′ 55 ″ E