Battle of the Boca do Tigre

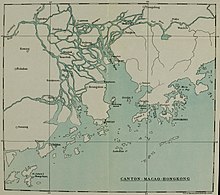

The Battle of Boca do Tigre ( German battle on the throat of the tiger ) was a series of sea battles between Portuguese ships and Chinese pirate fleets under Zhèng Yīsǎo (widow Cheng) between September 15, 1809 and January 21, 1810. They took place near Macau in the Waters of the Bocca Tigris (Humen) and ended with the dissolution of the pirate fleet after a peace agreement. The victory over the pirates is described as the last great success of the Portuguese naval power.

prehistory

In 1805, piracy increased in the waters around the Portuguese colony Macau and threatened the sea trade that was vital for them. On March 31, 1805 , the superior governor of India Francisco António da Veiga Cabral da Câmara Pimentel criticized Caetano de Sousa Pereira , the governor of Macau, for the fact that those ships that were actually intended to defend the area around Macau had meanwhile reached Penang operated in the Strait of Malacca . On October 20, 1805, Lieutenant Captain João Inácio Lopes and his brig Princesa Carlota , with 14 guns and a crew of 120, forced 70 pirate ships to flee. But the piracy continued. On November 29, 1805, the Macau Senate forbade the purchase of two-masters, under threat of a fine of 400 tael , because they could not arm themselves adequately.

In 1807 the pirates even dared to attack ships within sight of Macau. The Senate therefore equipped three ships. In addition to the 20-ton brig Princesa Carlota , under the command of Lieutenant Pereira Barreto, these were the 120-ton frigate Ulisses , with 28 guns and 100 men, under artillery captain José Pinto Alcoforado de Azevedo e Sousa and the Lorcha Leão , with five guns and a crew of 30, under navigator José Gonçalves Carocha. The flotilla, led by Pereira Barreto, left the port of Macau in April 1807 and encountered the Chinese pirate fleet, which consisted of 50 junks, on May 6, 1807. After an hour of fighting, the Chinese fleet withdrew down to the 20-ton flagship with a crew of 300. The Princesa Carlota took it under fire and eventually won a victory.

The battles at Boca do Tigre

The pirates Zhèng Yīsǎo and Zhāng Bǎozǎi (張 保 仔, Quan Apon Chay, Cheung Po Tsai) have been devastating the coasts of China with their fleets since 1805 . It was said that Zhāng Bǎozǎi aspired to become emperor of China . The country has been ruled by the Manchurian Qing dynasty since 1644 . Emperor Jiaqing had been in power since 1796 . After the death of her first husband, the pirate prince Cheng I, Zhèng Yīsǎo had made her adoptive son Zhāng Bǎozǎi one of the leading captains of her fleet as well as her lover and together with him built an armada of 700 ships, mostly junks , lorchas and smaller ships. It was called the Red Fleet because of its flags. For a long time they had spared shipping around Macau, presumably to avoid a conflict with the Portuguese. But when the frigate Ulisses was assigned to India, Zhāng Bǎozǎi began to ambush merchant ships from Macau.

In September 1808, the British also urged the establishment of a garrison in Macau. This was justified with the protection of the Portuguese colony from possible French attacks as a result of the Napoleonic Wars . Others saw it as an attempt at British appropriation, as Portugal was overrun by the French and João VI. had fled to Brazil with the royal court . It was not until 1815 that Portugal regained full control of its colonies.

On December 26, 1808, Lucas José de Alvarenga took over the post of Portuguese governor of Macau. To remove the threat to the city's prosperity posed by the pirates, Alvarenga commissioned the lieutenant governor and ombudsman Miguel José de Arriaga Brum da Silveira to set up a new squadron. The brig Princesa Carlota , now with 16 guns, became the flagship again. The proven artillery captain José Pinto Alcoforado de Azevedo e Sousa became the squadron chief. The Lorcha Leão under navigator José Gonçalves Carocha was also used again. In addition, there was the brig Belisário with 18 guns and a crew of 120 under the command of Ensign (Alferes) José Félix dos Remédios. The commander of the British frigate Mercury , anchored in the port of Macau, promised to cooperate, but stayed at anchor when the Portuguese ships set sail on September 15, 1809. On the morning of the same day, 200 ships from the pirate fleet of Zhāng Bǎozǎi were encountered. In the battle until sunset, the pirates tried again and again to get within range of the Portuguese ships while they fired cannons and rifles at the swarm of junks and lorchas. With many badly damaged ships, the pirates eventually withdrew.

This victory of the Portuguese "David against Goliath" damaged the reputation of the dreaded Red Fleet. The imperial Chinese government sent envoys to Macau to propose joint action against the pirate. On November 23, 1809, an agreement was signed in which the Portuguese undertook to erect six ships. China wanted to provide 60 ships. Arriaga then converted four more merchant ships into warships in just five days: the frigate Inconquistável with 26 guns and 160 men, which Azevedo e Sousa now chose as its flagship, the Indiana brigantine with 24 guns and 120 men under Ensign Anacieto José da Silva, the brig Conceição with 18 cannons and a crew of 130 under navigator Luís Carlos de Miranda and the brig São Miguel with 16 guns and a crew of 100 under navigator Constantino José Lopes. The Belisário was again commanded by Remédios. The Leão had probably suffered too much damage in the previous battle and was therefore not used. Their commander Gonçalves Carocha, who had excelled in combat, was now given command of the Princesa Carlota . Only the Princesa Carlota was owned by the city, the other ships were rented. The cost of 12,000 patacas was beyond the Senate's financial resources, and Arriaga had to take out personal loans from local merchants in order to complete his mission. Only a hundred men in the fleet were Portuguese and other Europeans. Most of the teams were Asians. Ammunition was largely supplied by the British East India Company .

On November 29, 1809, the fleet set course for the Boca do Tigre, as the place where the Pearl River expands to the Zhujiang Kou Bay , was called in Portuguese, in order to meet the imperial fleet there. But only a few hours after departure, the Portuguese were intercepted by the pirate fleet and a nine-hour sea battle ensued. Several junks were sunk by the Portuguese cannons, others badly damaged, whereupon the pirates eventually withdrew. Another battle broke out near Macau on December 11th. 15 pirate ships were sunk here and the pirates fled again. Because the Chinese imperial fleet had not appeared all the time, the Portuguese eventually returned to Macau. Through a messenger, Zhāng Bǎozǎi offered to spare Portuguese ships in the future. Azevedo e Sousa rejected this and asked Zhāng Bǎozǎi to accept the emperor's offer of amnesty . The pirate turned down the offer on December 18, unlike Guo Podai, the leader of the allied Black Fleet, who submitted to the emperor in January 1810. Zhāng Bǎozǎi even offered Portugal that if they supported him with four ships to overthrow the Manchurian dynasty, the Portuguese could choose two or three provinces of China. Portugal rejected the offer, which, if successful, would have changed world history.

At the beginning of January 1810, the Portuguese squadron ran out again and fought two more battles with the fleet of Zhāng Bǎozǎi on January 3rd and 4th off Lantau Island . Again the Portuguese were able to keep the pirates at a distance with their firepower so that the pirates could not attack the Portuguese ships directly. On January 21, Zhāng Bǎozǎi led a fleet of 300 ships, 1,500 cannons and 20,000 men to bring about the decision. The Portuguese ships maneuvered the pirates, however, so that the Europeans stood windward to the privateers. Unreachable from here, they fired continuous fire from their cannons and muskets. In the course of the battle, however, the Conceição ran aground and threatened to be boarded. Gonçalves Carocha then came to her aid with the Princesa Carlota . She managed to make the Conceição afloat again. Azevedo e Sousa then noticed that a pagoda had been built on a large junk in the middle of the pirate fleet . Assuming it was a religious symbol of the pirates, the Portuguese fleet commander had his ship's artillery fire focused on the pagoda. In fact, it represented the oracle and the temple of Zhāng Bǎozǎi, decorated with statues of gods. After several hits, the pagoda broke apart and the junk sank. The remaining pirate ships broke off the fight and fled to the Hiang-San River (Heang Shan) , where the Portuguese ships could not follow them due to their draft. These anchored at the mouth and blocked the exit.

Peace agreement

After about two weeks, Zhang Bǎozǎi sent a messenger and agreed to negotiate with an envoy. Azevedo e Sousa decided to go by himself and crossed alone in a boat to the pirates' flagship. Zhāng Bǎozǎi was impressed by the daring. The latter admitted to the Portuguese that he had actually intended to use the negotiations for an outbreak. But now he has changed his mind and is now ready for real peace negotiations, including with the Chinese emperor. To this end, he asked for mediation by the Portuguese lieutenant governor Arriaga, who enjoyed great esteem among the Chinese. Arriaga and the emperor's envoy, Bai Ling, finally negotiated with Zhèng Yīsǎo and Zhāng Bǎozǎi on February 21, 1810, but were unable to complete the negotiations completely successfully because the Qing were unwilling to comply with the pirates' demands . There was agreement that the emperor's authority should be unreservedly recognized, but the number of ships that Zhāng Bǎozǎi could continue to command was in question. It was contractually agreed that the authority of the emperor would be recognized by Zhèng Yīsǎo and Zhāng Bǎozǎi. In return, Zhāng Bǎozǎi was appointed Grand Admiral at the suggestion of Arriaga, endowed with numerous privileges. On April 12, Zhāng Bǎozǎi arrived at the agreed place to hand over his fleet. The contracts were signed on April 15, and on April 17, Zhèng Yīsǎo went alone to final negotiations with Bai Ling in Guangzhou, where she was finally able to largely enforce the demands of the Red Fleet. As a result, the fleet was handed over on April 20. It still consisted of 360 ships, 16,000 men and 5,000 women, 1,200 guns and 7,000 small arms and swords. Together with the pirates who surrendered further east and those who preferred to flee, it is now assumed that Zheng Yīsǎo's entire pirate force at that time consisted of 70,000 men with 1,800 ships and boats. But not everyone benefited from the amnesty: some who surrendered in Hiang San were denied it. 126 pirates were beheaded, 158 banished for life and 60 for two years. Apart from the ships captured in the last battle, the Portuguese renounced a share of the fleet. Both Zhèng Yīsǎo and Zhāng Bǎozǎi, however, kept all of their looted riches. The Portuguese share consisted of 50 cannons that João VI. were sent to Rio de Janeiro to fight Napoleon . One historian states that these were cannons that were actually armed with the Portuguese ships and that their value did not even cover the cost of shipping. According to the treaty with the Empire, half of the booty would have been granted to the Portuguese. It is not known why Arriaga did without it. But even half of the booty would only partially have been enough to pay off Macau's debts, which had been taken out for the fight against pirates. Since 1801, the colony had raised 370,000 patacas for this. Of the agreed 80,000 tael that the empire had promised to participate in the company, only 55,000 tael had been paid. China owed the rest to the Portuguese in Macau. The 480,000 taels Macau borrowed from its traders were never paid back.

Later, Zhāng Bǎozǎi visited Macau with a fleet of 60 festively decorated junks, where he was welcomed with full honors by the Senate. His relationship to Zhèng Yīsǎo, who was his adoptive mother, was formally dissolved by the governor and the two married. Zhèng Yīsǎo then ran a gambling den in Canton and participated in the opium smuggling and salt trade.

A street in Macau was later named after Miguel José de Arriaga Brum da Silveira. There are no memorials to the battle.

See also

- Zheng Yisao

- Battle of the Humen (1841)

literature

- Andrade, José Ignácio de: Memórias dos feitos macaenses contra os piratas da China e da entrada violenta dos inglezes na cidade de Macao , Typografia Lisbonense, Lisbon 1835.

- Esparteiro, António Marques: Três Séculos no Mar , Ministério da Marinha, Lisbon 1980.

- Saturnino, Monteiro: Portuguese Sea Battles Volume VIII: Downfall of the Empire 1808-1975 .

- 《張 保 仔 投降 新書》 收錄 於 蕭國健 、 卜永堅 箋 註 , (清) 袁永 綸 著 《靖海 氛 記》》 箋 註 專 號 , 田野 與 與 文獻 , 第 46 期 , 2007.01.15 [1]

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Marinha de Guerra Portuguesa: Batalhas e Combates-1805 a 1810 , accessed June 14, 2021.

- ↑ a b Pablo Magalhães: PAULINO DA SILVA BARBOSAO BAIANO QUE LIDEROU A REVOLUÇÃO CONSTITUCIONAL EM MACAU E CRIOU O JORNAL A ABELHA DA CHINA (1822-1823) , Afro-Ásia, 51 (2015), pp. 275-310, 275.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Richard J. Garrett: The Defences of Macau: Forts, Ships and Weapons over 450 year. Hong Kong University Press, 2010, limited preview in Google Book search.

- ↑ Murray, Dian H: One Woman's Rise to Power: Cheng I's Wife and the Pirates. Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques . 1987, p. 67 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Luís Gonzaga Gomes: The destruction of the fleet of Kam-Pau-Sai , Edif. do Instituto Cultural , accessed June 18, 2021.

- ↑ José Ignacio de Andrade: Memoria dos feitos macaenses contra os piratas da China: e da entrada violenta dos inglezes na cidade de Macáo , Typografia lisbonense, 1835, limited preview in the Google book search.

- ^ Siu, Kwok-kin; Puk, Wing-kun: 《靖海 氛 記》 原文 標點 及 箋 註 " [An Annotation on Yuan Yonglun's Jing Hai Fen Ji]. Fieldwork and Documents: South China Research Resource Station Newsletter (Chinese) .

- ↑ David Cordingly: Under a black flag. Legend and reality of pirate life . Munich 2001.

- ^ Bertil Lintner: Blood Brothers: Crime, Business and Politics in Asia .