Shinto

Shintō ( Japanese 神道 , is mostly translated in German as “way of the gods”) - also known as Shintoism - is the ethnic religion of the Japanese (see also Religion in Japan ) . Shinto and Buddhism , the two most important religions in Japan, are not always easy to distinguish due to their long common history. As the most important feature that separates the two religious systems, Shinto is often cited as being related to this world . In addition, the classical Shintō does not know any holy scriptures in the sense of a religious canon, but is largely passed on orally. The two writings Kojiki and Nihonshoki , which are considered sacred by some Shinto-influenced new religions in Japan , are more historical and mythological testimonies.

overview

Shinto consists of a variety of religious cults and beliefs that are directed towards the native Japanese deities ( kami ) . Kami are unlimited in number and can take the form of people, animals, objects, or abstract beings. One speaks therefore of Shinto as a polytheistic and animistic or theophanic religion.

The buildings or places of worship of Shinto are known as Shinto shrines . At the top of the shrine hierarchy is the Ise shrine , where the sun deity Amaterasu , also the mythical ancestor of the Japanese emperor, the Tennō , is venerated. Accordingly, the Tennō is also considered the head of Shintō. While this religious leadership role of the Tennō has only nominal significance today, it reached its climax in the era of nationalism before the Second World War . The tennō was then assigned a divine status. One speaks in this context of State Shinto .

Historically, the Shinto was for centuries an inconsistent religious tradition connected with elements of Buddhism and Confucianism , which was only interpreted by the state as a unified and purely Japanese "original religion" at the beginning of the Meiji Restoration due to new political ideologies . There is still no agreement on a precise definition. So noticed z. B. the Japanese religious historian Ōbayashi Taryō:

"Shintō ... [is] the original religion of Japan in the broadest sense, in the narrower sense a system developed from the original religion and Chinese elements for political purposes."

Important deities of Shinto are the primary gods Izanagi and Izanami , who play a decisive role in the Japanese myth about the origin of the world. From them the sun goddess Amaterasu , the storm god Susanoo , the moon god Tsukuyomi and many other kami emerged. Most Shinto shrines today, however, are dedicated to deities such as Hachiman or Inari . Both deities do not appear in the classical myths and were heavily influenced by Buddhism.

Word meaning

The word shintō comes from the Chinese where it is pronounced shendao . Shen means "spirit (he), god / gods", dao is the "way".

In Japanese, the character shin 神 is also read jin or kami . Kami is an old name for deities and has slightly different nuances than the Chinese shen . The term kami can also refer to deities of other religions, e.g. B. refer to the Christian God. Tō 道 in shintō is also read dō or michi and, similar to Chinese, can be used in a figurative sense for terms such as “teaching” or “school” (see Dao and compare Judo , Kendō , ...).

As early as the second oldest Japanese imperial history, the Nihon Shoki (720), is shinto mentioned, but only a total of four times. It is also still a matter of dispute what the exact term used to describe the word ( see below ). As a term for an independent religious system in the sense of today's usage, shintō only appears in sources from the Japanese Middle Ages .

Identity Features

The ambiguous, polytheistic nature of the native gods (kami) makes it difficult to find a common religious core in Shinto. Shinto has neither a founder figure nor a concrete dogma . The uniform characteristics of Shinto are primarily in the field of rite and architecture. The " Shinto shrine " is therefore one of the most important identity-creating features of the Shinto religion. Various Japanese expressions (jinja, yashiro, miya, ...) correspond to the expression “shrine” , but all of them clearly indicate a Shinto building and not a Buddhist one. In the narrower sense, a shrine is a building in which a divine object of worship ( shintai ) is kept. In a broader sense, the term refers to a "shrine facility" that can include a number of main and secondary shrines, as well as other religious buildings. There are certain optical or structural identifiers that can be used to identify a Shinto shrine. These include:

- torii ("Shinto gates"): simple, distinctive gates made up of two pillars and two crossbars, which are mostly free andsymbolizethe access to anarea reservedfor the kami .

- shimenawa (“ropes of the gods”): ropes of different strengths and lengths, mostly made of plaited straw, which either surround a numinous object (often trees or rocks) orare attachedto torii or shrine buildingsas a decorative element.

- Zigzag paper (shide, gohei ): A decorative element mostly made of white paper that can also serve as a symbolic offering. Often attached to god ropes or a staff.

Shrines can also be characterized by a characteristic roof decoration: It usually consists of X-shaped beams (chigi), which are attached to both ends of the roof ridge, as well as some ellipsoidal cross timbers ( katsuogi, literally "wood [in the form] of the bonito -Fish "), which are lined up between the chigi along the ridge. However, these elements can mostly only be found on shrines in the archaic style.

The objects of worship (shintai) kept in the shrines are considered the “seat” or “place of residence” of the revered deity and are never shown. Typical shintai are objects which, in the early days of Japan, when their respective production was not yet mastered in the country itself, came in small numbers from the Asian mainland to Japan and were considered miracles there; including bronze mirrors, swords or the so-called "curved jewels" ( magatama ) . But statues or other objects can also serve as shintai . In some cases the appearance of the shintai itself is unknown to the priests of the shrine.

The shrine priests themselves wear ceremonial robes that are derived from the official robes of court officials in ancient Japan. You are u. a. characterized by headgear made of black colored paper (tate-eboshi, kanmuri) . A specific ritual instrument is the shaku, a kind of scepter made of wood, which formerly also functioned as a symbol of worldly rule. All these elements also characterize the traditional ceremonial robes of the Tennō.

Following

Official statistics named around 100 million believers for 2012, which corresponds to around 80% of the Japanese population. According to another source, however, the number of believers is only 3.3% of the Japanese population, or about four million.

The difference between these figures reflects the difficulty in defining Shinto more precisely: The first survey is based on the number of people who are seen by the shrines themselves as community members ( ujiko ), which result from participating in religious rituals in the broadest sense ( like the traditional shrine visit at New Year ). From a sociological point of view, this corresponds to the feeling of belonging to an ethno-religious group , which sees many Shintoist aspects such as ancestral cult or belief in spirits as an inseparable part of Japanese culture. An actual affiliation to a religious community cannot be derived from this. If you ask explicitly about your belief in the Shinto religion, as in the second survey, the result must inevitably be significantly lower.

history

Prehistory

The oldest myths of Japan, which are considered to be the most important source of Shinto, suggest that the religious rites related to awe-inspiring natural phenomena (mountains, rocks or trees) as well as to food gods and elementary natural forces, which were predominantly agrarian at the time Society mattered. To describe the totality of all deities, the myths use the expression yao yorozu, wtl. "Eight million", which is to be understood in the sense of "uncountable", "unmanageable". This gives an indication that the religion of that time was not a closed, uniform belief system.

Like all ancient Japanese culture, this religion was probably related to the Jōmon culture , the Yayoi culture and the Austronesian religions, which found their way mainly over a land bridge from Taiwan over the Ryūkyū Islands in the south to Japan. In addition, early Korean and classical shamanistic cults from Siberia (via Sakhalin ) as well as influences from Chinese folk beliefs that came to Japan via the Korean peninsula are suspected. According to Helen Hardacre, Shintoism and Japanese culture are derived from Yayoi culture and religion. It must be borne in mind that in prehistoric times Japan was not populated by a single, ethnically homogeneous group and that even in historical times waves of immigration from the continent led to local cultural differences. The so-called "Ur-Shinto" therefore consisted of local traditions that may have been significantly more different than is the case today. A certain standardization only came about in connection with the establishment of the early Japanese state, the formative phase of which was completed around the year 700. The earliest written sources come from the Nara period immediately following the political consolidation ( Kojiki : 712, Nihon shoki : 720). Many questions about the prehistoric Japanese religion remain open due to a lack of sources. All this has led to the fact that research hardly uses the term "Shinto" in connection with the prehistoric, pre-Buddhist religion (or better: the religions) of Japan, but rather uses neutral terms such as " kami worship", served. In many introductory works, however, the equation "Shintō = original Japanese religion" can still be found frequently.

Mythology and Imperial Rite

When a hegemonic dynasty established itself in central Japan in the 5th and 6th centuries, a courtly cult emerged that was increasingly oriented towards the Chinese state and culture. Here, playing both the ancestor worship and the morals of the Chinese Confucianism and the, cosmology of Taoism and salvation faith of Buddhism a role. All these traditions were combined with the cults of indigenous territorial and sound deities ( Ujigami ) to create a new type of state ceremony.

The early Japanese state emerged from alliances of individual clans (uji), each of which worshiped its own Ujigami. When the clan of the later Tennō ("emperors") asserted itself as the leading dynasty within this alliance, a mythology arose which merged the stories of the individual sound deities into a unified mythological tale. The earliest text sources of this mythology from the eighth century already mentioned describe the origins of the world and the origin of the Tennō dynasty: A pair of primitive gods ( Izanagi and Izanami ) created the Japanese islands and all other deities. Amaterasu Omikami (heavenly, great deity) is the most important of her creations: She rules the “heavenly realms” ( Takamanohara ) and is equated with the sun. On her behalf, her grandson descends to earth to establish the everlasting dynasty of the Tennō family. This mythological idea of the origin of Japan and its imperial line forms a central idea in all later attempts to systematize Shinto (e.g. in Yoshida Shinto , Kokugaku or State Shinto ). The term "Shinto" itself appeared at this time, but was not used in the sense of a systematic religion. The so-called "office of gods" ( 神祇 官 , Jingi-kan ), the only ancient government institution that does not correspond to any Chinese model, does not have the designation "Shinto office" (as sometimes stated in Western literature), but is literally the " Authority for the gods of heaven ( 神 , jin or shin ) and earth ( 祇 , gi ) ”- again an ultimately Chinese concept.

Shinto Buddhist syncretism

Buddhism , which was newly introduced in the 6th and 7th centuries , initially encountered resistance as part of the local worship of gods, but quickly found ways to integrate the kami into his worldview and influenced, among other things, the buildings and later also the iconography of the kami worship . During most of the epochs of the known Japanese religious history, there was no clear separation between Buddhism and Shinto. Especially within the influential Buddhist schools of Tendai and Shingon , Shinto deities were seen as incarnations or manifestations of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas . Buddha worship and kami worship thus served the same purpose - at least on a theoretical level. This theological development began in the Heian period and reached its peak in the Japanese Middle Ages (12th – 16th centuries). It is known as the theory of " archetypal form and lowered trace", whereby the " archetype " ( 本地 , honji ) corresponds to the Buddhas, the "lowered trace" ( 垂 迹 , suijaku ) corresponds to the kami .

Most of the kami shrines were under Buddhist supervision between the later Heian period (10th – 12th centuries) and the beginning of Japanese modernism (1868). Although the great Shinto institutions were in the hands of hereditary priest dynasties who were originally subordinate to the imperial court, with the decline of the court, Buddhist institutions took its place. Only the Ise shrine retained a special position, thanks to its privileged relationship with the court, and escaped the direct influence of the Buddhist clergy. Smaller shrines, on the other hand, usually did not have their own Shinto priests, but were looked after by Buddhist monks or lay people.

First Shinto theologies

Although most Shinto priests were devout Buddhists themselves at that time, there were individual descendants of the old priest dynasties and also some Buddhist monks who were concerned with the idea of worshiping the kami independently of Buddhism. In this way, the directions Ise- or Watarai-Shintō, Ryōbu-Shintō and Yoshida-Shintō emerged in the Japanese Middle Ages . The latter direction in particular presented itself as a teaching that was purely related to the kami and thus represents the basis of modern Shinto, but Buddhist ideas actually played a central role in Yoshida Shinto. A fundamental criticism of the religious paradigms of Buddhism only became conceivable under the so-called Shinto-Confucian syncretism.

In the course of the Edo period there were repeated anti-Buddhist tendencies, which also gave the ideas of an independent indigenous Shinto religion ever greater popularity. In the 17th century it was mainly Confucian scholars who looked for ways to combine the teachings of the Chinese neo-Confucian Zhu Xi (also Chu Hsi, 1130–1200) with the worship of indigenous deities and thus to develop an alternative to Buddhism. In the 18th and 19th centuries a school of thought emerged which tried to cleanse the Shinto of all "foreign", that is, Indian and Chinese ideas and to find its "origin". This school is called Kokugaku in Japanese (literally teaching of the country ) and is considered to be the forerunner of State Shinto, as it emerged in the course of the 19th century in the course of the reorganization of the Japanese state. However, the Kokugaku had little influence on general religious practice in the Edo period. Thus, the Shinto Buddhist syncretism remained the dominant trend within the Japanese religion until the 19th century. The casual access to both religions in today's Japan is based on this tradition.

Modern and present

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 ended the feudal rule of the Tokugawa - Shoguns and installed in its place a modern nation-state with the Tennō as the highest authority. Shinto was defined as a national cult and used as an ideological tool to revive the power of the Tenno. For this purpose a law for the "separation of kami and Buddhas" ( Shinbutsu Bunri ) was passed, which forbade the joint worship of Buddhist and Shinto shrines. In contrast to the mostly locally limited shrine traditions, Shinto shrines were now reinterpreted nationwide as places of worship of the Tenno and every Japanese, regardless of their religious convictions, was required to pay their respects to the Tenno in the form of shrine visits. In consideration of the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of religion under Western influence, this shrine cult was not defined as a religious act, but as a patriotic duty. In the interwar period, this form of worship was referred to as " Shrine Shinto " (jinja shinto), but in the post-war period it was mostly referred to as " State Shinto " (kokka shinto) . In addition, there was also the category " Sect Shinto " (shuha shinto), in which various new religious movements that arose in the course of modernization and defined themselves as Shinto ( Tenri-kyō , Ōmoto-kyō, etc.) were summarized.

In the burgeoning militarism of the Shōwa period , Shintō was then further instrumentalized for nationalist and colonialist purposes. Shrines were also built in the occupied territories of China and Korea, in which the local population should pay their respects to the Tennō. After Japan's defeat in World War II in 1945, Shinto was officially banned as the state religion, and in 1946 the Tenno renounced any claim to divinity. Individual institutions that are said to be politically close to State Shinto, such as the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, still exist today.

ethics

Shinto has few clearly defined concepts of religious ethics in its entire history . There are no written commandments that would have been valid for all believers or even all people at all times. The orientation towards the Tennō as the highest authority is not undisputed even in the so-called shrine Shintō , while the directions of the so-called sect Shintō usually revere their own founder figures as the highest religious authority. A difference to Buddhist, Confucian or merely secular ethics is often not discernible. However, some general tendencies are generally attributed to ethical practice in all directions:

- A lifestyle is advocated in accordance with the Kami , which can express itself in admiration and gratitude towards them, and above all in striving for harmony with their will (especially through conscientious execution of the Shinto rituals). In shrine Shinto in particular, consideration must be given to the natural as well as one's own social environment and order. In this emphasis on mutual aid-based harmony, which can also be extended to the world as a whole, a commitment to human solidarity can be found, as is also characteristic of the universalistic world religions.

- The kami are much more “perfect” than humans, but not perfect in an absolute sense, such as in monotheism . Kami commit mistakes and even sins. This corresponds to the fact that there are no moral absolutes in Shinto. The value or disqualification of an action results from the totality of its context; Bad actions are generally just those that damage or even destroy the given harmony.

- Purity is a desirable state. Accordingly, pollution ( kegare 穢 ) of both physical and spiritual nature should be avoided and regular cleansing rituals ( harai 祓 ) should be held. Purification rituals are therefore always at the beginning of all other religious ceremonies of Shinto. In the historical development of Shinto, this has led to a general taboo on death and all related phenomena. Therefore, burial ceremonies in Japan are mostly incumbent on Buddhist institutions and clergy. In addition, organ donations or the posthumous release of dead bodies of relatives, e.g. B. to the autopsy , so as not to disturb the spiritual connection between the dead and the mourners and not to injure the body. In recent years, however, voices from high clergymen have also been raised against the latter tendencies.

Religious practice

In the modern everyday life of the Japanese, both Shinto and Buddhism play a certain role, although the majority see no contradiction in professing both religions. In general, there is a tendency to use Shinto rites for happy occasions (New Years, weddings, prayer for everyday things), Buddhist ones for sad and serious occasions (death, prayer for welfare in the hereafter). Recently, a kind of secular Christianity has been added, for example when young Japanese people celebrate a white wedding ( ホ ワ イ ト ウ エ デ ィ ン グ , howaito uedingu ), a white wedding in American style.

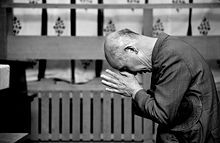

Regular gatherings of the entire religious community in accordance with Christian masses are alien to Shinto (as well as Japanese Buddhism). Usually shrines are visited individually. The deities are worshiped with a few simple, ritual gestures of respect (bowing, clapping hands, donations of small sums of money). A priest is only cared for by a special request.

Special rituals performed by priests mostly have to do with purity and protection from danger. Shinto priests are z. B. always called before a new building is erected to consecrate the ground. Ordination rites for cars are also popular, analogous to western ship baptisms . Around the Shichi-go-san festival on November 15th, many Japanese hold purification ceremonies (harai) for their children in the shrines .

The climax of the religious life of the Shinto shrines are periodically held Matsuri , folk festivals that follow local traditions and can therefore be very different from region to region, even from village to village. Many Matsuri have to do with the agrarian annual cycle and mark important events such as sowing and harvesting (fertility cults), in other Matsuri elements of evocation and defense against demons can be seen. Many matsuri are also associated with local myths and legends. Shrine parades are a typical element. The main shrine ( shintai ) of the shrine in question is reloaded into a portable shrine, the so-called Mikoshi , which is then carried or pulled through the village / city district in a loud and happy pageant. Fireworks ( 花火 , hanabi ), taiko drums and of course sake mostly accompany these parades. Matsuri are also often associated with quasi-athletic competitions. The modern sumo sport, for example, is likely to have its origin in such festivals.

In today's practice, the Tennō cult only plays a central role in a few shrines. These shrines are commonly referred to as jingū ( 神宮 ) (as opposed to jinja ( 神社 )), the most important of which is the Ise shrine . Although the "law for the separation of Buddhas and Shinto gods" brought radical changes with it, the traces of the former Shinto-Buddhist mixture can still be seen in many religious institutions today. It is not uncommon to find a small Shinto shrine on the site of a Buddhist temple or a tree marked with a Shimenawa as the place of residence of a kami . Conversely, many Shinto deities have Indian Buddhist roots.

Important deities and shrines

Most Shinto shrines today are dedicated to the deity Hachiman , an estimated 40,000 nationwide. Hachiman was the first native god to be promoted by Buddhism, but also received influential support from the warrior nobility (the samurai ) as the ancestral deity of several Shogun dynasties . The deity Inari , a rice deity, whose shrines are mostly guarded by foxes ( kitsune ) , has a similar number of mostly very small shrines. The third most common category is tenjin shrines, where the Heian temporal scholar Sugawara no Michizane is worshiped as the god of education. Even Amaterasu , the most important ancestral deity of Tennō, outside their main sanctuary of has Ise a relatively large network of branch shrines, all other deities mentioned in the old myths, however, are represented in much less shrines. On the other hand, numerous shrines are originally dedicated to Buddhist deities, above all the shrines of the seven gods of luck . The most magnificent shrine complex from the Edo period, the Tōshōgū in Nikkō , is a mausoleum of the first Tokugawa shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu .

The Ise shrine in the city of Ise is considered to be the highest shrine in Japan in the shrine Shinto. Another significant and ancient shrine is the Izumo Grand Shrine . The most popular shrine in Tōkyō is the Meiji Shrine , which houses Emperor Meiji and his wife.

A controversial political issue is the Yasukuni shrine in Tōkyō , in which all those who have fallen in Japanese wars have been venerated since around 1860. Even war criminals sentenced to death after the Second World War, such as Tōjō Hideki , were accepted into the Yasukuni shrine as kami. The main shrine festival of Yasukuni Shrine takes place every year on August 15th, the anniversary of the end of the war in East Asia , and is sometimes attended by leading politicians on the occasion. This indirect negation of Japan's war guilt regularly provokes protests within Japan, but above all in China and Korea.

See also

- State Shinto | Shrine Shinto | Sectarian Shinto | Yoshida Shinto

- Religion in Japan | Japanese gods | Japanese mythology

- Sindo (Korean: 신도 or 神道)

literature

- Klaus Antoni : Shinto and the conception of the Japanese national system (kokutai): The religious traditionalism in modern times and modern Japan . In: Handbook of Oriental Studies. Fifth Division, Japan . tape 8 . Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 1998.

- Ernst Lokowandt: Shinto. An introduction . Iudicium, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-89129-727-0 .

- Nelly Naumann : The Native Religion of Japan . 2 volumes, 1988–1994. Brill, suffering.

- Bernhard Scheid: Shintō Shrines: Traditions and Transformations . In: Inken Prohl, John Nelson (Eds.): Handbook of Contemporary Japanese Religions . Brill, Leiden 2012, p. 75-105 .

Web links

- Bernhard Scheid: Religion in Japan, a web manual with numerous Shinto-relevant articles.

- Encyclopedia of Shinto online encyclopedia published by Kokugaku-in Shinto University.

- Mark Schumacher: Photo Dictionary of Japanese Shintoism, Guide to Shinto Deities (Kami), Shrines, and Religious Concepts (English)

- Glossary of Shinto Names and Terms - Kokugakuin University

- Andrea Kath: December 15, 1945 - Shintoism no longer the state religion WDR ZeitZeichen from December 15, 2015 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ^ Rabbi Marc Gellman et al. Monsignor Thomas Hartman: Religions of the World for Dummies. 2nd, updated edition, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, special edition 2016, ISBN 978-3-527-69736-6 . Part V, Chapter 13: Texts of Shintoism. (E-book).

- ↑ See Klaus Antoni : Shintō . in: Klaus Kracht, Markus Rüttermann: Grundriß der Japanologie . Wiesbaden 2001, p. 125 ff.

- ↑ Ōbayashi Taryō: Ise and Izumo. The shrines of Shintoism , Freiburg 1982, p. 135.

- ↑ The term shendao can be found in the I Ching . In today's Chinese, shendao can also refer to the access route to a temple. The famous Temple of Heaven in Beijing , for example, has a shendao .

- ↑ 第六 十四 回 日本 統計 年鑑 平 成 27 年 - 第 23 章 文化 (64th Statistical Yearbook of Japan, 2015, Section 23 Culture). 23-22 宗教 (religion). (No longer available online.) Statistics Bureau, Ministry of the Interior and Telecommunications, archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; Retrieved August 25, 2015 (Japanese). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ adherents.com : Major Religions Ranked by Size - English; Retrieved June 10, 2006

- ↑ Inoue Nobutaka, Shinto, a Short History (2003) p. 1

- ↑ Shamanism in Japan; By William P. Fairchild ( https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/457 )

- ↑ Hardacre, Helen (2017). Shinto: A History . Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-062171-1

- ↑ An epoch-making discussion of this topic can be found in the essay "Shinto in the History of Japanese Religion" by Kuroda Toshio, Journal of Japaneses Studies 7/1 (1981); However, similar considerations are already contained in the “Comments on the so-called Ur-Shinto” (PDF file; 1.2 MB) by Nelly Naumann , MOAG 107/108 (1970), pp. 5-13

- ↑ A total of thirteen new religious sects were officially referred to as sects Shinto before 1945.

- ↑ Shinto Online Network Association: Jinja Shinto: Sins and the Concept of Shinto Ethics ( Memento of the original of January 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - English; Retrieved June 10, 2006

- ↑ BBC: BBC - Religion & Ethics - Shinto Ethics ( Memento of the original from April 11, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - English; Retrieved June 10, 2006

- ↑ Basic Terms of Shinto: Kegare - English; Retrieved June 14, 2006

- ↑ Traditional pronunciation: harae , s. Basic Terms of Shinto: Harae - English; Retrieved June 14, 2006

- ↑ BBC: BBC - Religion & Ethics - Organ Donation ( Memento of the original from September 2, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - English; Retrieved June 10, 2006

- ↑ California Transplant Donor Network - Resources - Clergy ( Memento of the original from June 21, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - English; Retrieved June 10, 2006

- ↑ Yukitaka Yamamoto, High Priest of Tsubaki-O-Kami-Yashiro: Essay on the 2,000th anniversary of the shrine in 1997 ( Memento of the original from September 25, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked . Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - English; Retrieved June 10, 2006