Japanese mythology

Under Japanese mythology ( Jap. Shinwa 神話 ) commonly refers to the oldest written chronicles of Japan held stories and legends from prehistoric time to the partially historically verifiable early rulers of Japan ranging from the origin of the world. In these stories special emphasis is placed on the genealogical connections between the Japanese gods ( kami ) and rulers ( tennō ). These so-called classical myths of Japan are also among the most important texts of Shinto , the indigenous religion of Japan. They are therefore sometimes referred to as "Shinto myths".

The difference between the classic myths and later stories, in which the world of the supernatural plays a role, is fluid. The later myth-like traditions are often heavily influenced by Japanese Buddhism .

The myths of the age of the Japanese gods

Sources

The period between the creation of the world and the beginning of the rule of the tennō dynasty is referred to in the language of myths as the "Age of the Gods" ( 神 代 , kamiyo or jindai ). The myths of this time are mainly written down in the two chronicles Kojiki ( 古 事 記 , "Chronicle of old incidents", 712) and Nihonshoki ( 日本 書 紀 , "Chronicle of Japan", 720) from the 8th century, which are summarized as Kiki ( 記 紀 ) are designated. The narratives are arranged chronologically, with many episodes having several variants, some of which differ only slightly and some significantly from the main variant. These differences within the Kiki can partly be traced back to different regional traditions, but could also be ascribed to politically different groups that were involved in the writing of the chronicles. Overall, however , the mythology of the Kiki shows a high degree of internal coherence.

Other early sources, the Fudoki ( 風土 記 , "Regional Chronicles " from 713), also contain mythological material, which - in contrast to the Kiki - is not contained in a coherent narrative and has surprisingly few similarities with the Kiki .

Later sources, starting with the Kogo Shūi and the Sendai kuji hongi from the early 9th century, reproduce the Kiki myths of the age of the gods in a synthesized form (with innovations being introduced at some points that are not considered here). (More on the reception of myths, see below)

Creation of the world

Both chronicles, both the Kojiki and the Nihon shoki , begin with the creation of the world. At the beginning, the so-called primordial matter is divided into heaven and earth and in between there are three sky gods and seven generations of gods, each appearing in pairs. Special attention is paid here to the seventh and thus last generation, consisting of a pair of primordial gods who are responsible for the actual creation of the world.

The primal gods Izanagi and Izanami , who are both siblings and a married couple, initially stand on the floating sky bridge and watch the chaos below. Eventually Izanagi stirs around in the water with a spear, and when he withdraws the spear, salty drops fall back into the water and an island - Onogoroshima ( 淤 能 碁 呂 島 , "the island that coagulates by itself") - is created. The pair of gods now descend on the newly created land, erect a "heavenly pillar" and perform a kind of wedding rite. As a result, numerous islands emerged, including the eight large islands of Japan ( 大 八 島 , Ōyashima), as well as a large number of gods.

After numerous deities have been conceived in the form of land masses or natural elements, the great mother Izanami burns herself so badly during the birth of the fire god that she “dies” and goes to the underworld (“ Yomi ”). In his grief, his father Izanagi cuts the fire god to pieces with a sword, creating new gods, and then goes in search of Izanami. He eventually finds her in the underworld, but violates her request not to look at her, whereupon Izanami chases him from the underworld along with her creatures. When he has passed the gate to the underworld, he closes it with a rock and thus separates the world of the living from the world of the dead. In revenge, Izanami swears to destroy a thousand lives every day, and thereby becomes the ruler of the underworld. Izanagi, on the other hand, becomes the god of life by swearing to create a thousand wards (births) every day. In this way the cycle of life and death is set in motion.

After his visit to the underworld, Izanagi performs a ritual cleansing in a river. In turn, several deities arise, including the sun goddess Amaterasu , who appears when washing the left eye, the moon god Tsukiyomi no Mikoto (also called Tsukuyomi) when washing the right eye and the god Susanoo , who appears when washing the nose. Before Izanagi finishes his creative work and "withdraws", he assigns these children various domains: Amaterasu receives the high realms of the sky , Tsukiyomi the realms of the night and Susanoo the realms of the sea or - in some variants - the earth.

What remains the same in all mythological versions of the allocation of domains is that Susanoo, instead of taking care of his domain, acts like a defiant child, weeps terribly, and thereby allows rivers and forests to dry up; he initiates death in the world. Therefore he is banished to the root country ( 根 の 国 , "Ne no kuni"), over which he is to rule from now on.

Amaterasu and Susanoo

Before Susanoo goes to his new domain, he wants to say goodbye to his sister Amaterasu . He climbs up to her in the sky, makes the earth shake and sets mountains and hills in motion. Amaterasu expects an attack and suspects that he is trying to steal their land. So she prepares for battle and changes her appearance so that she now resembles a man. Once at the top, Susanoo asserts, however, to be "pure of heart". To prove this, the divine brothers and sisters enter into a competition. It is a kind of incantation ( ukehi ), in which a previously identified sign is considered a positive or negative answer to a question asked. In this case it is about the creation of children from the weapons of the respective sibling deity, whose gender should ultimately also provide information about Susanoo's attitude. How exactly this is done differs from version to version - but they all have in common that the result is always interpreted in Susanoo's favor.

So it happens that Susanoo gains access to Amaterasu's realm. There he commits eight “heavenly sins” ( ama-tsu-tsumi ); For example, he destroys the rice fields, lets go of the horses or smears the sacred hall in which Amaterasu tastes the freshly harvested rice with his own droppings. Amaterasu initially does nothing to counteract these acts of sabotage, but when he finally pulls the skin off a horse by "backward tearing", throws it into the holy weaving hall and a weaver there stabs her sheath in shock with the shuttle and dies, he closes it Driven far: Amaterasu is so angry that she locks herself in a rock cave, whereby the light of the world goes out.

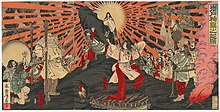

Lure from the rock cave

The gods then forge a plan to lure the sun goddess out of her cave so that the light can return to the world. First they begin with the production of various offerings such as a mirror or curved jewels and finally uproot a sakaki tree , which is located on the heavenly Kagu mountain.

The offering of the offerings, which is accompanied by flattering ritual words, is followed by a dance by the goddess Amenouzume , who - in a trance as it were - bares her breasts and genitals. This approach makes the surrounding gods laugh, whereupon Amaterasu, having become curious, opens the gate of the cave and looks out into the open. The god Ame no Tachikarao (“man of the strong hand of heaven”), who has positioned himself next to the entrance, uses this and pulls Amaterasu out of her cave into the open, whereupon the world lights up again. The god Ame no Futotama immediately stretches a rope across the entrance to prevent Amaterasu from hiding in the cave again.

Variants of this episode also mention roosters that are made to crow by the gods, possibly to trick Amaterasu into thinking that the sun rose without them.

Susanoo and the eight-headed monster

Susanoo is finally banished from heaven after the sun deity reappears. He descends into the province of Izumo , where he meets an old couple who tell him about their misfortune. The eight-headed monster Yamata no Orochi has already devoured seven of its eight daughters, and the time will soon come when it will also devour its eighth daughter Kushinadahime . Susanoo promises to kill the monster if he gets Kushinadahime for his wife. The couple agrees and so Susanoo instructs the two to brew eight barrels of rice wine ( sake ) and to build a fence with eight openings behind which they should place the barrels of sake.

When Yamata no Orochi finally comes to get Kushinadahime, Susanoo respectfully offers the sake to the monster. Yamata no Orochi drinks, falls asleep and can be cut to pieces by Susanoo. In the monster's tail he finds the sword Ama no Mura-kumo ( 天 叢 雲 , "Heavenly cloud heaps"), which later receives the name Kusanagi no Tsurugi (see below: Yamato Takeru ).

Ōkuninushi

Next, the myths tell of Ōkuninushi ( 大 国 主 or Ōnamuchi 大 己 貴 ・ 大 穴 牟 遅 , Ōmononushi 大 物主 ), a descendant (or son) of Susanoo . In Kojiki there are very detailed and almost fairytale descriptions of Ōkuninushi.

Inaba's white rabbit

For example, Ōkuninushi and his 80 half-brothers go to Inaba ( 因 幡 ), where the brothers want to marry the "Princess Yakami" ( 八 上 ). Ōkuninushi follows them and carries the brothers' luggage. On their journey, the brothers meet a white (naked) rabbit that is squirming on the ground in pain. Ōkuninushi asks him why he is naked. He explains to him that he wanted to get from the island of Oki to the mainland and therefore deceived the sea monsters ( wani ) with a ruse and that a deceived sea monster snapped off his skin. Ōkuninushi advises the suffering animal to bathe in fresh water and wallow in pollen, thereby relieving its pain. The rabbit, who is actually a deity, prophesies that he will marry Princess Yakami. When the rabbit's prophecy comes true and Princess Yakami takes Ōkuninushi as husband, the brothers' contempt turns into hatred.

Promotion to "Lord of the Country"

After escaping several attacks on his life, Ōkuninushi flees to the underworld, where he meets Susanoo's daughter Suseri-bime ( 須 勢 理 毘 売 ), whom he takes as his wife. Susanoo is not very fond of his new son-in-law and gives him three tasks, all of which Ōkuninushi manages with the help of his wife and a family of rats. Ōkuninushi steals the sword of life, arrows and bow of life and the heavenly proclamation zither and flees with Suseri-bime on his back. Susanoo wakes up, pursues Ōkuninushi and calls after him to kill his brothers and make himself the god Ōkuninushi ("Great Ruler of the Land"). He thus gives him a mandate to rule.

Ōkuninushi's adventures are described in great detail , especially in Kojiki , while Nihon shoki only briefly mentions that with Sukunabikona no Kami ( 少 名 毘 古 那 神 ), a kind of medicine god, he sets out to heal mankind from illness and by means of defensive magic against dangerous things To protect animals. Both deities are worshiped in numerous shrines in Japan; among other things, there is an old connection to the Ōmiwa shrine in today's Nara prefecture .

Land handover

In Nihon shoki , Ōkuninushi's (or Ōnamuchi's) most important role is the so-called handover of land ( kuniyuzuri 国 譲 り ), in the course of which he more or less voluntarily cedes his kingdom to the heavenly gods. For this purpose, Amaterasu initially sends various heralds, including a. Futsunushi and Takemikazuchi to subdue the “Central Plateau of the Reed Fields” (Japan). These two deities descend from heaven on Inasa Beach in Idzumo, demonstrate their martial superiority with some sword tricks and ask Ōkuninushi whether he would not hand over the land to the heavenly deities. After some back and forth (which in some variants is associated with compensation payments to Ōkuninushi) Ōkuninushi finally agrees and thanks. (The episode can be interpreted as a reminder of the takeover of the once powerful province of Izumo into the Yamato Empire .)

Descent of the Heavenly Grandson

The following part of the myth deals with the commission of the heavenly deities Amaterasu and Takamimusubi to Ninigi no Mikoto , the heavenly grandson ( tenson 天 孫 ), to descend from heaven and rule the "land of the reeds" (Japan, the earthly world).

In the chronicles the myth has two strongly diverging versions: In the first, by far better known version, Amaterasu and Takamimusubi hand over the three insignia of the throne ( 三種 の 神器 , sanshū no jingi ) - the mirror, the sword and the jewels - and proclaim to the heavenly grandson his mandate to rule. Some other deities are asked to accompany the heavenly grandson to earth and to perform tasks there in the spirit of the heavenly deities. For example, the so-called "five professional group leaders", a group of deities that are put together differently depending on the chronicle. When the heavenly grandson Ninigi and the deities begin their descent, a first problem opens up for them: a "grim" deity confronts them on the heavenly paths. Amenouzume , a female deity who appeared in the myth of the rock cave (see above), is sent ahead to consult the disturbing deity. Before Ame no Uzume, the supposed troublemaker reveals himself as the deity Sarutahiko , whose real intention was to lead the heavenly grandson to earth and lead the entourage of descending deities. So Sarutahiko shows Ninigi the way and he descends to the top of Mount Takachiho . This mountain can still be located today and is located in what is now Miyazaki Prefecture in Kyūshū , the southernmost of the four main islands of Japan.

The second version of the myth is much more concise than the first. Here it is reported that Takamimusubi (without Amaterasus doing anything) envelops the heavenly grandson with a "covering everything" blanket and then lets him descend to earth. Ninigi ends up alone on Mount Takachiho and wanders around the rugged land for some time, until a local deity, this time Koto-katsu-kuni-katsu Nagasa, assigns him a suitable land. Ninigi builds his palace there.

Finally, Ninigi marries the daughter of the local mountain deity Ōyamatsumi ( 大 山 津 見 ) and establishes a dynasty with her, from which the first Japanese “emperor” ( tennō ) will emerge. In some myths, Ninigi's wife is called Konohanasakuyahime ( 木花 之 開 耶 姫 , the "princess who makes the blossoms of the trees bloom") and is also worshiped as the deity of Mount Fuji . This flower princess has a sister named Iwanaga-hime ("Princess Long Rock"), whom Ninigi disdains because of her ugliness. Since he has given preference to beauty over strength, the life of his offspring (humanity) is as short as that of flowers.

Mountain happiness and sea happiness

This myth describes the union of heavenly rule with the rule of the sea.

The story is about the fate of the two brothers Hoderi and Hoori, sons of Ninigi and his wife Konohana-sakuya-hime, and ends with the birth of Jinmu Tennō and his three siblings. Hoderi, the " Prince of Fortune at the Sea " ( 海 幸 彦 , Umisachihiko ), exchanges his fishing hook for the hunting bow of his younger brother Hoori, the " Prince of Fortune on the Mountain " ( 山 幸 彦 , Yamasachihiko ). Hoori is awkwardly fishing and loses his brother's fishhook. While Hoori complains about the great loss, the god of seafaring Shiotsuchi no kami ( 塩 椎 神 ) appears, with whose help Hoori reaches the palace of the sea god Watatsumi ( 綿 津 見 ).

In the realm of the sea god, Hoori meets Toyotama-hime ( 豊 玉 姫 ), the princess and daughter of Watatsumi, and they fall in love. After three years in the Sea Palace, Hoori returns to shore with his brother's fishhook, as well as flood climbing and flood sinking jewels that he received from Watatsumi. Hoori hands the fishhook to Hoderi. But Hoderi gradually loses happiness, for which he blames his brother and attacks him. Hoori defends himself with the jewels of the sea god and torments Hoderi until he submits to him.

Toyotama-hime leaves the sea to give birth to her son Hiko Nagisatake Ugayafukiahezu ( 彦波 瀲 武 鸕鶿 草 葺 不合 尊 ), the father of Jinmu Tennō , on the coast . Since Hoori breaks the taboo at birth not to look at Toyotama-hime under any circumstances, she returns ashamed to her father Watatsumi and closes the path into the sea behind her.

Instead of Toyotama-hime, her sister Tamayori-hime takes care of the newborn and eventually even becomes Hoori's wife. Together they father four offspring, including Jinmu Tennō. The age of the earthly emperors begins.

General characteristics of the age of gods

In the stories outlined above one comes across the categories “heavenly gods” ( 天津 神 , amatsukami ) and “earthly gods” ( 国 津 神 , kunitsukami ). Obviously, they are gods of different status, with the heavenly gods representing a kind of aristocracy that subdues and rules the ancestral inhabitants of the earthly world, the "earthly gods". The heaven from which the heavenly gods descend is called Takamanohara ( 高 間 原 , the "High Heavenly Realms") in the myths and in many aspects it seems to be a true reflection of the political center in early historical Japan. In fact, all named heavenly gods also functioned as ancestral deities of those families who held the most important offices at court at the time the myths were written in the early eighth century.

This genealogical connection between the nobility and the gods is probably one of the reasons why the difference between gods and humans is of degree and is nowhere clearly established in myths. The difference between "heavenly" and "earthly" families sometimes seems more decisive than the difference between kami (deity) and man. Conversely, the vague differentiation between kami and humans certainly made it relatively easy to describe the Tennō as a manifest deity ( arahitogami 現 人 神 or akitsu mikami 現 御 神 ), as it was especially in the 8th century ( Shoku Nihongi ) and much later, under the state -Shintō in the 20th century, was the case in Japan.

On the other hand, many modern mythologists equate the heavenly gods with the continent, especially Korea . Theories such as the so-called "equestrian people hypothesis" ( 騎馬 民族 説 , kiba minzoku setsu ) of the archaeologist and historian Egami Namio are therefore derived from the myths , according to which the aristocracy of Japan emerged from a nomadic people, which only relatively later Time (4th century C.E. ) invaded Japan and established a state structure.

In any case, the myths of the age of the gods reveal a special mix of widespread mythological motifs (see below) with very specific genealogical episodes that had normative significance for the political conditions of the early imperial court.

Mythological-historical rulers and heroes

From today's perspective, with the beginning of the tennō dynasty , the mythical tale slowly merges into the realm of history. Even the very first periods of rule are carefully given annual dates in the Japanese chronicles, but these are not considered historical facts today, because many stories of the early tennō still have mythical traits. Their lifetimes and periods of rule (similar to the mythological emperors of China ) are also unrealistically long. The most famous mythological or semi-mythological rulers of Japan include:

Jinmu Tennō

Jinmu Tennō , a descendant of Ninigi no Mikoto , occupies an important place in the mythological history of the imperial family, as he is regarded as the first human ruler ( tennō , "emperor") and a large part of Japan (from Kyūshū to Yamato , today Nara Prefecture ) is said to have united under his rule. The central element in the myth about Jinmu is his campaign from Kyūshū to the east. a. is discussed in detail in the Kojiki and Nihonshoki . In several places it is described how Jinmu can use cunning and divine help to defeat his adversaries (various human army leaders, but also enemy gods / demons, e.g. those from Kumano ). Yatagarasu the crow heads the imperial army in the mountains of Uda. After subjugating his enemies, Jinmu designates Kashiwara in Yamato as his residence. The myth thus explains the relocation of the Japanese Empire from western to central Japan.

Yamato Takeru

Versions of the legend of Yamatotakeru ( 日本 武 尊 , for example: "the hero of Yamato / Japan") can be found next to Kojiki and Nihonshoki in the Fudoki (local chronicles from the early 8th century). Most of the stories focus on the campaigns of Yamato Takeru and the divine power of the Kusanagi sword .

On the orders of his father Keikō Tennō , the twelfth Japanese "emperor", Yamato Takeru travels to the western provinces (Kyūshū) to punish the rebellious Kumaso , an ethnic group in the south of Kyūshū. After their submission, Takeru returns to Yamato , this time moving east to fight the "barbaric" Emishi . On these campaigns he defeated a myriad of unruly "deities" and rebellious clans. According to the chronicles, Yamato Takeru succeeds in asserting the power of the imperial court in the distant areas of the country and laying the foundations for the unification of the country under one central power. (A generation later, Seimu Tennō sends members of the imperial family to the remote regions of the empire to delimit the individual provinces.)

The Kusanagi sword plays an important role in the story of Yamato Takeru as part of the three imperial insignia . It is brought from the Imperial Palace to the Ise Shrine under the eleventh tennō Suinin because of its fearsome power . The chief priestess Yamato Hime , an aunt of Yamato Takerus, keeps it there, but passes it on to her nephew when he visits her before his campaign to the east. With the sword, Yamato Takeru succeeds in carrying out his conquests in the east. In particular, it helps him to put out a steppe fire, from which the name Kusanagi, "grass mower", is supposed to be derived. Takeru eventually dies on his way back to the capital after recklessly putting down the sword. The sword remains in the hands of his wife and then becomes the central cult object of the Atsuta shrine in what is now Nagoya.

In the Fudoki , Yamato Takeru is sometimes represented as tennō and associated with numerous place names. The heroic role of Yamato Takeru was further embellished in the Heian period and in the Japanese Middle Ages in the form of various shrine legends.

Jingū Kōgō and Ōjin Tennō

Jingū Kōgō (Okinaga Tarashi no Mikoto) was a legendary ruler (possibly a fictional amalgamation of several rulers) and appears in the chronicles as the wife and later widow of the fourteenth ruler, Chūai Tennō . She is said to have lived for a hundred years, from AD 169 to AD 269.

Through Jingū's mouth, anonymous deities give her husband Chūai the order to conquer the Korean kingdom of Silla . However, the latter doubts the authenticity of the message, which infuriates the deities and leads to his quick death. The imperial widow Jingū then took control of the troops herself and conquered Korea in a three-year campaign. During this time, she delays the birth of her son with stones attached to her lower abdomen.

Her son, who later became Ōjin Tennō, was finally born on her return to Kyūshū. He wears one time in the form of an archer's bracelet ( homuda ) on his forearm, which is interpreted as a good omen and gives him the proper name Homuda. At the age of seventy, he inherited his mother in order to rule for many more years and reaped the fruits of her military conquests: It was under him that scribes from Korea were said to have come to the country for the first time and spread knowledge of the Chinese characters. In later times, Ōjin is identified with Hachiman , a deity also from Kyushu.

Historical hero figures

The historical times of Japan also know numerous hero figures, around whom myth-like legends entwine, which are still known to every child in Japan today. These include:

- Minamoto no Yorimitsu ( 源 頼 光 , also Raikō, 948-1021) and his four vassals, who are monsters like the demon of the city gate Rajōmon (also Rashōmon), the "earth spider" ( tsuchigumo ), or the man- eater Shuten Dōji ( 酒 呑 童子 ) put.

- Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159–1189) and his vassal Benkei (1155–1189) who, despite their heroic deeds in the Gempei War , were murdered under the orders of Yoshitsune's brother Yoritomo (1147–1199). Later legends suggested that Yoshitsune trained in sword fighting with the warlike mountain spirits, the tengu , or let him escape to Mongolia, from where he conquered almost all of Asia as Genghis Khan .

- The 47 ronin who avenge their master Asano Naganori, who was sentenced in 1701 to commit seppuku for attacking a court official of the shogunate with a dagger. This had been assigned to instruct Asano in court etiquette, but had only treated him with condescension and publicly insulted him. Asano's vassals then swear vengeance, which they successfully carry out. The rōnin are sentenced to death, due to their honorable behavior they are allowed to die by seppuku .

Other myths and legends

Buddhist legends

In addition to the life of the Buddha, which as part of an organized religion cannot really be called “myth”, Buddhism also brought a large number of Indian (“Hindu”) myths to Japan and found their way into the country's mythological narrative tradition. Examples would be the seven gods of luck , in particular the figures Benzaiten (skt. Sarasvatī), Bishamonten (Vaiśravaṇa) and Daikokuten (Mahākāla), or the figure of the legendary Indian monk Bodhidharma .

Various Buddhist Bodhisattvas also achieved great popularity in Japan and were firmly anchored in the religious and mythological world of the spirit through legends that arose in Japan. The best known of these Buddhist salvation figures include Kannon ( 観 音 , skt. Avalokiteśvara ), Jizō ( 地 蔵 , Kṣitigarbha ) and Fudō Myōō ( 不 動 明王 , Acala Vidyārāja).

Finally, there are complex legends surrounding some historical Buddhist figures, which in the course of Japanese history were at least as important as the stories of the mythological gods. These "Buddhist folk heroes" of Japan include figures such as Shōtoku Taishi , En no Gyōja or the important monk Kūkai . The oldest collection of Buddhist legends, in which Japanese Buddhist figures were elevated to mythological heroes, is the Nihon Ryōiki (around 800).

Chinese legends

The Chinese mythology has probably exerted an influence on the Japanese mythology already historically ago period. However, the similarities are not so strong that one could infer a direct relationship between Japanese and Chinese myths. In historical times, however, Chinese myths and legends became part of the Japanese educational canon, similar to the classical sagas of antiquity in Europe. The best-known characters that are used again and again in Japanese storytelling include: B .:

- Pangu ( 盘古 ), the first being between heaven and earth, often thought of as a human giant, from whose body the earth in its present form emerges.

- Yao and Shun , two “original emperors” of China, who are often mentioned in the same breath as symbols of ideal rulers. They are two of the mythological Five Great Emperors ( 五帝 , wudi ). Yao is said to be from 2333–2234 BC. BC, Shun from 2233-2184 BC Have lived. Japanese rulers have sometimes been compared to these models.

- The weaver and the cowherd: Known in Japan as the Tanabata legend ( chin.qixi七夕), it is a Chinese legend of the love of a heavenly deity (the weaver) and a person (the cowherd), which is not possible in the long term is. The desperate lovers are eventually transformed into the stars Altair and Vega , which are usually separated by a "river" (the Milky Way ), but come close once a year. On this day ( the 7th day of the 7th month according to the traditional calendar ) traditional summer festivals take place in both China and Japan.

Fairy tale motifs

There are also many fairy tales in Japan that (as in the western world) are about beautiful princesses and brave boys.

- Urashima Taro is a fisherman who saves a turtle from a few children. Then a large turtle visits him and explains to him that the rescued turtle is a daughter of the sea god Ryūjin and asks for a visit. On the seabed in the palace of the sea god, he meets the little turtle Otohime, who is now a beautiful king's daughter. Urashima Taro spends a few happy days with her, but finally asks to be allowed to return to see his old mother. She lets him go and gives him a box ( tama tebako ), which he is never allowed to open. Back on land, Urashima finds neither his mother nor his village and has to realize that three hundred years have passed. He opens the box, loses the gift of eternal youth, suddenly ages and dies.

- Kaguyahime or Taketori Monogatari tells the story of the beautiful princess of the moon Kaguya. She is found by a bamboo collector in the forest. Like Thumbelina , it is very small. But soon she grows into a beautiful woman that every man would like to have a wife. However, none of the men can perform the tasks given to them by Kaguyahime. Finally, the radiant princess leaves the earthly world and returns to the moon.

Myth transmission and research into myths

Text maintenance by priests and monks

In addition to the primary sources Kojiki , Nihon shoki and Fudoki , other texts were created in ancient Japanese that contain variants of the myths of the gods. These include above all the Kogo Shūi ( 古語 拾遺 , possibly 807) by Inbe no Hironari ( 斎 部 広 成 ) and the apocryphal Sendai kuji hongi ( 先 代 旧 事 本 紀 , also Kujiki , around the 9th century).

The transmission of these classic mythical texts was limited to the beginning of the Edo period (1600-1867) to a narrow circle of courtly ("Shinto") priest-officials who jealously guarded the few copies, but from time to time at the court of the tennō lectures held to it. The oldest surviving manuscripts mostly come from the libraries of these families, especially the Urabe ( 卜 部 ). The myths are also passed on in the form of shrine legends. Here, individual episodes were often extensively decorated according to the needs of the respective shrine.

In the Japanese Middle Ages (12th to 16th centuries), Buddhist monks began to incorporate the classical myths into theological treatises, mostly to explain them in accordance with Buddhist teachings. An early example is the Kuji hongi gengi ( 旧 事 本 紀玄義 , 1333) from Jihen ( 慈 遍 ), a Tendai monk who came from the Urabe family mentioned.

Rationalist interpretations of myths

The beginning of the 17th century marked a political and intellectual turning point in Japan with the establishment of the Tokugawa military government ( bakufu ) . Buddhism was increasingly associated with militant sects and put in a negative light, which allowed the implementation of a fresh teaching imported from China, Neo-Confucianism . Neo-Confucian thought was used as a universal framework in all scientific disciplines of the Edo period (1600–1868) and at the same time marks the beginning of modern historical research in Japan.

Hayashi Razan (1583-1657) is with his work Honchō Tsugan ( 本 朝 通鑑 ), which was completed by his son Hayashi Gahō (1618-1680), as the founder of modern historical research in Japan, through critical text analysis and a certain Wise rationalistic or "positivistic" conception of history is shaped. Nevertheless, Hayashi in Honchō Tsugan seems to accept the mythological representation of the origin of the Japanese islands and the imperial line in the "Age of the Gods". He only tries to adapt them to Confucian-metaphysical ideas and to interpret them in the sense of Confucianism. Similarly, the Mitō school, which combines loyalism (uncritical acceptance of the emperor's legitimacy and his heavenly origin) and rationalism in the sense of modern historical research, is convinced of the historicity of Japanese myths.

Another turning point in the direction of modern Japanese historical research was the Orthodox Confucian Arai Hakuseki (1657–1725), who not only dealt with the classical chronicles, but also with the work Sendai Kuji Hongi ( 先 代 旧 事 本 紀 ), which he considered to be authentic, argued. With his interpretation of deities as humans (an interpretation known as euhemerism ), he is considered the first pure rationalist in Japan.

Yamagata Bantō (1748–1821), who was influenced by Western science, recognized the Confucian ideas of moral and social order, but rejected all metaphysical concepts. In contrast to Hakuseki, Yamagata denied the age of the gods in his work Yume no Shiro ( 夢 の 代 ) and did not feel obliged to provide a rationalistic explanation of its historicity.

The national school

Although Japanese history received new attention under the influence of the Confucians, the philological preoccupation with the classical myths was reserved for a school of thought that is retrospectively referred to as the “national school” ( kokugaku 国学 ) and its heyday under Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801) experienced. The kokugaku scholars resorted to the original texts of the early chronicles, which were hardly understood at that time, reconstructed the old readings on the basis of text comparisons and in this way established a textual understanding that is still the basis of Japanese mythology today. This intensive text maintenance was motivated by a nostalgia for a golden age, which the kokugaku believed to recognize in the prescribed time, when Japan was not yet "spoiled" by continental influences - be it Buddhism or Confucianism. In this respect, the philological work, which must be taken seriously, is also mixed with a strong xenophobic basic tendency, which portrays the Japanese myths as an originally Japanese cultural heritage that is completely free from external influences. Linked to this was an idealization of the ancient tennō cult, which played an important role in the restoration of imperial rule in the 19th century.

Comparative mythology

While the upgrading of the tennō by the Meiji Restoration (1868) went hand in hand with increased attention to the imperial ancestral gods, the academic public also came under the influence of myth research in 19th century Europe. Both Western and Japanese scholars began to look at Japanese myths from a comparative perspective, that is, to relate them to the myths of other cultures and, for the first time, not to read them as historical factual reports. Instead, it was mostly about the question of the origin of myths, which was often equated with the question of the origin of Japanese culture.

For example, Kume Kunitake (1839–1932), who was trained in Confucian positivism, interpreted Japanese mythology in a completely new way. In 1891 he published an article entitled "Shinto is an ancient custom of worshiping the sky", in which he claimed that the sun deity , throne insignia and the Ise shrine are only part of an old primitive natural cult, Shinto , which only thanks to the Introduction of Buddhism and Confucianism had evolved. Although Kume's intention was a modern and rational interpretation of Shinto, his article was perceived as a criticism of Shinto and thus of the foundations of the new Japanese state. Kume then had to give up his professorship at the Imperial University in Tokyo.

At the same time, pioneers of Western Japanology such as William George Aston (1841–1911), Basil Hall Chamberlain (1850–1935) and Karl Florenz (1865–1939), who also translated the Japanese myths into their respective national languages, set new impulses in this area. These were taken up and further developed by Japanese historians and religious scholars at the beginning of the 20th century. Two main directions formed in Japan, the "northern thesis " ( hoppōsetsu 北方 説 ), which brought Japanese mythology primarily in connection with Korean influences, and the " southern thesis" ( nanpōsetsu 南方, ), which has similarities with the myths of Southeast Asia and the South Pacific region.

Korea

Japanese mythologists such as Mishina Shōei ( 三品 彰 英 ) (1902–1971), Matsumae Takeshi ( 松 前 健 , 1922–2002) or Ōbayashi Taryō ( 大 林太良 , 1929–2001) have repeatedly on motifs that are in both Japanese and in Korean legends occur, pointed out. Above all, myths of descent such as Ninigi's (see above) are often found in Korean mythology.

- In the classic Japanese myths, in addition to Ninigi (see above), we also meet his brother, Nigihayai , who rises from the sky with ten treasures. There is also the motif of returning to heaven, for example in the case of Amewaka-hiko , who dies after his descent to earth but is buried in heaven.

- According to the Korean collection of myths Samguk Yusa , the sky god Hwan'ung also descends from heaven with three holy imperial insignia and a large following on Mount Taebaek , marries a local princess and fathered King Dangun , who is said to have lived for 1500 years. It is similar with the ancestral god Hyeokgeose .

- The myth of King Suro says that he and five brothers were born from six golden eggs that floated down to earth in a red box.

Pacific Rim

The island world of the Pacific is another cultural area that has strong mythological relationships with Japanese myths. A common origin in South China or Southeast Asia is often assumed here. Matsumoto Nobuhiro (1897–1981), who studied in Paris and worked there with Marcel Mauss , is considered to be the first significant proponent of this so-called “southern thesis” . Oceanic myths that have parallels to Japan are, according to Matsumoto:

- The Māori hero Māui fishes land from the sea, similar to how Izanagi and Izanami create the first island in the sea.

- The marriage of Izanagi and Izanami on this island has parallels to sibling marriage in the myths of the Yanks , an indigenous group in Taiwan .

The Japanologist Klaus Antoni has also pointed out parallels between the story of the White Hare by Inaba ( Kojiki , Ōkuninushi cycle, see above) and myths of the Circumpacific region. The myth researcher Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) points out similarities with South American myths and lists the story under the "motif of the sensitive ferryman" (who is embodied in this case by crocodiles).

Universal motifs

Japanese mythology also has numerous motifs that can also be found, for example, in the ancient world of legends in Europe. One example among many is the above-mentioned underworld episode Izanagis and Izanamis, which has parallels to the Greek Orpheus myth. In the episode of Bergglück and Meerglück, more precisely in the figure of the sea princess Toyotama-hime, there are also surprising parallels to the European Melusine (or Undine ) myth.

A research approach that focuses less on the historical than on the psychological-mental foundations of such motifs is represented in the case of Japanese myth research by the German myth specialist Nelly Naumann (1922–2000).

Remarks

- ↑ Ame no Minakanushi no Kami, Takamimusubi no Kami and Kamumimusubi no Mikoto

- ↑ The first child Hiruko is a freak, which is attributed to a mistake by the woman in the wedding rite.

- ↑ Cf. Florence: The historical sources of the Shinto religion , 1919, pp. 41, 156-182, 424. The number eight, which is particularly emphasized in this episode, also functions in other episodes as a symbol for a multiplicity or totality , for example in the creation of the "eight islands" (= Japan) by Izanagi and Izanami or in the name of the "eight-fold towering clouds of Izumo" ( yakumo tatsu Izumo 八 雲 立 つ 出 雲 ).

- ↑ So Ōkuninushi is supposed to be responsible for the “divine affairs”, that is to say take on a kind of priest role and / or live in the palace Ama no Hisumi (which is to be built for him).

- ↑ Also known as Kamu Yamato Iwarehiko no Mikoto ( 神 日本 磐 余 彦 尊 ).

- ↑ This etymology seems implausible today, but is repeated several times in the primary sources.

- ↑ The same motif can also be found in the form of the Indian Purusha or the Ymir of northern European mythology. In Japanese myth, this universal myth motif appears in the form of the primordial mother Izanami (see above), from whose dead body field crops arise.

- ↑ The Mito school begins with the historical work Dai Nihon shi ( 大 日本史 , "History of Great Japan"), which was initiated by Tokugawa Mitsukuni (1628-1700), daimyo of Mito.

- ↑ Thanks to new printing techniques, these were accessible to wider circles for the first time.

- ↑ This episode is only included in the Sendai kuji hongi . Ōbayashi: Japanese Myths of Descent from Heaven and their Korean Parallels , 1984, pp. 171-172.

- ↑ Matsumae Takeshi connects this with the variant of ninigi according to which ninigi comes down to earth as a child, wrapped in royal bedding. See Matsumae: The myth of the descent of the heavenly grandson , 1983, p. 163.

- ↑ He published his first important work on this in French: Essai sur la mythologie japonaise (1928).

literature

- Klaus J. Antoni: The White Rabbit by Inaba: From myth to fairy tale. Analysis of a Japanese "myth of the eternal return" against the background of ancient Chinese and Circumpacific thinking (= Munich East Asian Studies . Volume 28 ). Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1982, ISBN 3-515-03778-0 ( uni-tuebingen.de [PDF; 14.0 MB ] Reprint of the dissertation from 1980).

- John S. Brownlee: Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600-1945 . UBC Press, Vancouver 1997, ISBN 0-7748-0644-3 .

- Karl Florenz : The historical sources of the Shinto religion . Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1919.

- Jun'ichi Isomae: Japanese mythology: Hermeneutics on scripture . Equinox, London 2010, ISBN 1-84553-182-5 .

- Claude Lévi-Strauss : The Other Side of the Moon: Writings on Japan . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2012.

- Takeshi Matsumae: The myth of the descent of the heavenly grandson . In: Asian Folklore Studies . tape 42 , no. 2 , 1983, p. 159-179 .

- Nelly Naumann : The Native Religion of Japan . Brill, Leiden (2 volumes, 1988-1994).

- Nelly Naumann: The Myths of Ancient Japan . CH Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-86647-589-6 .

- Taryō Ōbayashi: Japanese Myths of Descent from Heaven and their Korean Parallels . In: Asian Folklore Studies . tape 43 , no. 2 , 1984, p. 171-184 .

- Tarō Sakamoto: The six national histories of Japan . UBC Press, Vancouver 1970 (English).

- Bernhard Scheid: Two Modes of Secrecy in the Nihon shoki Transmission . In: Bernhard Scheid, Mark Teeuwen (eds.): The Culture of Secrecy in Japanese Religion . Routledge, London / New York 2006, pp. 284-306 .

Web links

- Klaus Antoni (Ed.): Kiki: Kojiki - Nihonshoki . (As of January 19, 2013).

- Camigraphy . (As of January 19, 2013). A wiki project on the iconography and iconology of Japanese deities, ed. by Bernhard Scheid (University of Vienna, since 2012).

- Bernhard Scheid: Myths, Legends and Beliefs . (As of January 19, 2013). In: Bernhard Scheid (Ed.): Religion-in-Japan: Ein Web-Handbuch (University of Vienna, since 2001).

Individual evidence

- ↑ The mythologist Levi-Strauss particularly emphasizes this feature of Japanese mythology. (See Levi-Strauss 2012, p. 23ff.)

- ↑ Cf. Florence: The historical sources of the Shinto religion , 1919, pp. 42–44, 164–170, 424–425.

- ↑ Cf. Florence: The historical sources of the Shinto religion , 1919, pp. 46–48.

- ↑ Cf. Florence: The historical sources of the Shinto religion , 1919, pp. 49–51.

- ↑ Cf. Florence: The historical sources of the Shinto religion , 1919, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Due to the archaeological findings , this theory is now considered outdated, but it always finds new representatives.

- ↑ See Scheid: Two Modes of Secrecy in the Nihon shoki Transmission , 2006.

- ↑ Brownlee: Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600-1945 , 1997, pp. 15-19.

- ↑ Brownlee: Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600-1945 , 1997, pp. 19-41.

- ↑ Brownlee: Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600-1945 , 1997, pp. 42-49.

- ↑ Brownlee: Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600-1945 , 1997, pp. 49-53.

- ↑ Brownlee: Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600-1945 , 1997, pp. 86-87; Sakamoto 1970, p. XX.

- ↑ Isomae: Japanese mythology: Hermeneutics on scripture , 2010, p. 99.

- ^ Brownlee: Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600-1945 , 1997, p. 105.

- ↑ Ōbayashi: Japanese Myths of Descent from Heaven and their Korean Parallels , 1984, pp. 172-173.

- ↑ Antoni: The White Hare by Inaba: From myth to fairy tale. Analysis of a Japanese "myth of eternal return" against the background of ancient Chinese and Circumpacific thinking , 1982

- ^ Levi-Strauss: The Other Side of the Moon: Writings on Japan , 2012, pp. 70–80.