Stampede Pass

| Stampede Pass | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pass height | 1119 m | ||

| Washington | King County / Kittitas County | ||

| expansion | Forest Service Road 54 | ||

| Mountains | Cascade chain | ||

| Map (Washington) | |||

|

|

|||

| Coordinates | 47 ° 17 '0 " N , 121 ° 21' 4" W | ||

The Stampede Pass (1,119 m high ) is a mountain pass in the Pacific Northwest of the United States across the Cascade Range in Washington State . Located southeast of Seattle and east of Tacoma , its importance to traffic is mainly due to the railroad , as there is no paved road crossing it. It is located approximately 20 km south-southeast of Snoqualmie Pass , the transition from Interstate 90 over the Cascade Range, and 3.2 km south of Keechelus Lake .

The pass and the 3 km long Stampede Tunnel located a little south of it at an altitude of almost 870 m played an important role in the history of the Northern Pacific Railway . The tunnel was opened as a traffic route in May 1888 and is currently operated by the successor to the NP, the BNSF Railway .

After over a decade of calm in the late 20th century, the Stampede Pass line and the tunnel in 1997 have been reopened by the BNSF which the route as a direct two Northern Transcon -Hauptlinien via the cascade between Spokane and Seattle metropolitan area uses .

Discovery of the pass

The pass was discovered by Virgil Bogue, a civil engineer for the Northern Pacific . (Bogue later left the NP to become chief engineer of the Union Pacific Railroad and later the Western Pacific Railroad .)

This is followed by Bogue's January 1881 report, from the collection of Robert A. Robey, who was primarily responsible for the Stampede Pass connection in the 1960s on the Northern Pacific at Auburn .

- “On about January 1, 1881, I received instructions from Col. Isaac W. Smith [a surveyor and civil engineer] to explore the Tacoma Pass , which JT Sheets discovered the previous fall; furthermore, the cascades to the north were to be included up to a certain point which covered all possible passes that lead down to the Green River in that direction. Last fall, four huts were converted into useful accommodations by a column led by Colonel Smith; the cabins are between Thorpe's Prairie , later known as Supply Camp , and a point four or five miles west of Tacoma Pass . A detachment of three or four men, well stocked, set out from Thorpe's Prairie during the winter, and were instructed to be ready for any assignment that might come. When we left Tacoma to begin exploring, instructions were sent to these men to cross the mountain range and build a fifth cabin as far as possible towards the Green River . They should try to meet our group by walking in our direction from the west.

- We left Tacoma without delay and went to McClintock’s , located on the watershed between White River and Green River (near Enumclaw ). From McClintock’s on, we were forced to pave a path through the bushes and fallen trees. We set up our first camp at McClintock’s on January 17, 1881. We worked constantly on the trail, occasionally leaving camp, and encamped on January 26, 1881, on the Green River at a point 500 ... 1000 feet [150 ... 300 m] east of the current second crossing of the river.

- Our camp on the Green River was Camp No. 5 .

- We continued our work on the path and reached our Camp No. 7 on February 8, 1881 on the Green River at the mouth of a river that we later called Canoe Creek because we tried to build a canoe there and failed. When we arrived the snow was about two feet high and frozen over. In our opinion, the pack animals could not go any further and it was simply impractical to leave the path. We therefore decided to use the sledges with which we were equipped and to carry them on our backs in the deep places where they could not be used. The squad was also equipped with snowshoes, but it was not always practical to use them.

- With pack animals and sledges carrying equipment to the hut on Canoe Creek , the squad continued and reached Camp No. 10 on February 19th. At this place we were forced to rest for four days, which we owed to a heavy rain that made all channels in the river rise to such an extent that it was practically impassable. On the morning of February 24th we set out again and shortly after leaving the camp saw a large eagle circling over our heads; We therefore called the camp we had just left Eagle Gorge .

- On March 2nd we reached Camp No. 13 on the Green River, not far from the mouth of what was later called that of Smay Creek (near Maywood). [ Smay Creek forms the western border of Nagrom, founded by Elmer G. Morgan in 1911. ] The work and demands of the party had discouraged some of the men since leaving Canoe Creek, as had before, and I decided to go with a small party of three or four without equipment and only provided with provisions for a few days to look for the hut which the other group described above was to build at Thorpe's Prairie .

- I instructed those who stayed behind to spend their time moving supplies from the Canoe Creek camp to their camp until they heard from me again. On the morning of March 3rd, I left with my companions Joe Wilson, the Indian Peter and the Indian Charley.

- The first camp, Camp No. Called 14 , just continuing the camp numbers from below, was not far from Green River Hot Springs on a hill. Our next camp, Camp No. 15 , was on a gravel bank in what we later called Sunday Creek , because we did a great job near Lester on this creek on the Sabbath. On the night of February 5th to 6th, we set up Camp No. 16 at the foot of the mountain range in the angle formed by Camp Creek and Sunday Creek (near Borup). We had therefore already passed the hut, which we later found about a mile [1.6 km] above the confluence of Sunday Creek and Green River. Our exploration led along the north bank of the Green River; of course we had followed Sunday Creek and, due to the heavy tree growth, had not seen any other larger tributaries.

- On the day we arrived at Camp No. 16 we realized that our Indian companions were of little use and only used up our supplies. We therefore sent them back with instructions to the main troop to bring more provisions and to follow our tracks. We stayed at Camp No. until the morning of February 9th . 16 , explored the rivers and mountain ranges in this place, hoping to find some traces of the hut of the men who were to meet us. While we were resting there, Joe Wilson set off on the way back and met the Indians who were supposed to get us more provisions.

- He sent the Indians back and brought all the provisions so that we could camp No. Left 16 on the morning of February 9th. We felt great. We concluded that the cabin we were looking for must be on a different branch of the Green River and continued our search on Sunday Creek , looking as best we could for other major rivers. We found these without difficulty and shortly afterwards we encountered signs and fire behind the trees, which indicated the presence of white people. When we finally found the hut, the men weren't there, but had apparently left several days beforehand. We soon found the path they had taken and followed it over the mountains. When we arrived at Tacoma Pass in a blizzard on March 9th at 5:45 pm, the aneroid barometer showed an altitude of 3,760 feet [1,146 m]. We continue our way over the pass and reached Cabin No. 3 on Cabin Creek near the mouth of Coal Creek after dark. On the following days we went to Thorpe's Prairie , where we found our friends. From this point I sent a messenger over the mountains who reached Tacoma by our trail in four days.

- To be well rested, we stayed at Thorpe's Prairie from March 10th to the morning of March 14th . Then we went to the Tacoma Pass . During the 14th, 15th, and 16th we explored Cabin Creek , Tacoma Pass, and the Pass called Sheet's Pass immediately to the north .

- On the morning of March 16, we left Cabin No. 3 , where we camped for our exploration near Tacoma Pass to walk north along the mountain range. We used snowshoes and carried the provisions we had. The snow was between seven and 30 feet [approx. 2… 9 m] high. We followed the main stream of Cabin Creek and climbed to a point 600 feet east of the range on the evening of the 16th, where we camped until morning. In the morning we climbed to the top and followed the chain to a high point south of it. From there we overlooked the sources of Camp Creek and Sunday Creek . Here one of the men tripped and fell down a steep slope until he was stuck in the snow.

- Because his snowshoe caused the fall, we named the mountain Snow Shoe Butte . butte = tip]. That night we camped below the ridge between the peak and Stampede Pass .

- The next day we tried to find the pass that we could clearly see from the top. The mountain range ran for a large distance to the southeast, obviously in the direction of the Yakima River . This deceived us about the direction we were taking and we walked back several times over the chain in the hope of finding one leading to the north, which we suspected to be in the main watershed. This search was ultimately unsuccessful and on the night of March 18th we camped at almost the same place as we had camped on the 17th. The weather on the 18th was cold and the mountain peaks were surrounded by a cold fog that sometimes turned out to be a blizzard.

- On the morning of the 19th, we left camp at 8:30 a.m. The weather was fine, not a cloud could be seen in the sky. We had finally decided to stay on the mountain range we were on. We pushed forward and were so lucky that we got to the pass at 10:10; the aneroid barometer indicated an altitude of 3,495 feet [1,065 m]. Andy Drury, one of the men, noticed when we looked down and saw the slopes of Sunday Creek and Green River that it was the most beautiful pass in these mountains. We only lingered a few moments and then continued north, exploring three more passes on our way on that successful day. From the northernmost pass, which we consider to be the last that led north to some tributary of the Green River , we explored a stream that flowed into Lake Kitchelos (now Kechelus). We arrived at Lake Kitchelos at 5:15 p.m. on March 21, and the next day at Cabin No. 1 , which still stands at the mouth of Cabin Creek . The following day we came to Thorpe's Prairie .

- By that time, more supplies were beginning to arrive from Ellensburg with which we could continue our discoveries. As we were already familiar with the land, we sent the supplies as soon as they arrived on sledges and on the men's backs to the Tacoma Pass . We gathered enough supplies there to start exploring on April 1st. The men I'd left on the Green River near Smay Creek had rejoined us and were being pursued by a great force throughout the season as they walked several stretches of the Tacoma Pass and Stampede Pass .

- All passes north of Stampede Pass have been inspected and sufficient instrumental studies have been carried out to determine their properties. As a result, the Stampede Pass was ultimately chosen as one of the most suitable in these mountains. Besides myself, the following men were involved in exploring the mountain range from Tacoma Pass northwards and discovered the Stampede Pass : James Gregg, Andy Drury, and Matthew Champion. Gregg was the cook. "

Name of the passport

Bogue wrote to William Pierce Bonney of the Washington State Historical Society in 1916 about the naming of the pass:

- “I had a road-building squad camped near Stampede Lake . This squad was controlled by a foreman who, in my opinion, didn't achieve much. When the other party who was supposed to pave the way from Canoe Creek up the Green River to my camp at the mouth of Sunday Creek finished their work, I sent their foremen to the camp on Stampede Lake , which was occupied by the above-mentioned party, with a letter authorizing him to take the lead. As a result, a large number of the aforementioned squad ran away wildly [to stampede = run away wildly]. There was a really large fir tree in that camp on Stampede Lake that had a large blaze struck by the remaining men. With a small piece of charcoal they wrote the words 'Stampede Camp' on this blaze. "

Bonney, who worked for the Northern Pacific at Stampede Pass , added: “When the men stopped work in the middle of the afternoon on the day of running away, they returned to camp, where they were busily waiting for dinner; when the foreman came and told the cook that the groceries were for the men who worked for the railroad company. These men have lost their connection to the company and should therefore not be fed; at this point the actual progression began. "

When explored a few weeks earlier, the Garfield Pass had been named in honor of the recently-appointed President Garfield, but Stampede Pass became the commonly used name.

The hairpin at the top of the pass

The Northern Pacific completed the Stampede Tunnel under the Stampede Pass in 1888 (see section below). In the meantime, however, the NP decided not to wait for completion and built a hairpin at the top of the pass.

According to A Brief History of the Northern Railway (German: "A Brief History of the Northern Railway") a hairpin with a 5.6 percent gradient was examined by the chief engineer Anderson from 1884 at the earliest. The route was explored in the spring of 1886. There were three switchbacks on each side of the cascade and a large double horseshoe at the top of the pass. During the construction of the hairpin, snowfalls hit the workers; a cut through 12 meter high snow at the top of the pass was necessary. The hairpin included a mile (1.6 km) of solid timber cladding, 3/4 mile (1.2 km) snow protection roofs and 31 trestle bridges . When the ground was thawed in the spring of 1887, the newly laid tracks shifted and again generated work. The Northern Pacific spent US $ 15,000 protecting work during the construction of the hairpin.

To operate the route, the Northern Pacific ordered two of the largest steam locomotives available in the world at the time. Regardless of their size, the steep gradients made it necessary to place one of these locomotives at each end of a five-car train. The trains took an hour and fifteen minutes to make the eight mile (13 km) hairpin; a brakeman was also required on every second car. The first test train over the hairpin drove on June 6, 1887. The first scheduled passenger train to use the hairpin arrived in Tacoma on July 3, 1887 at 7:15 in the evening.

Even after the tunnel was completed, the hairpin was used for brief periods in the 1890s when maintenance work in the tunnel was necessary.

Stampede tunnel

| Stampede tunnel | ||

|---|---|---|

|

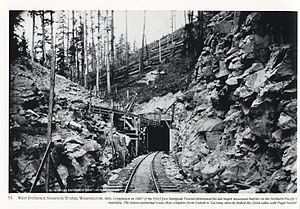

West entrance 1890 by Frank Jay Haynes

|

||

| use | Railroad (freight transport) | |

| place | Stampede Pass, Washington , USA | |

| length | 3000 m | |

| Number of tubes | 1 | |

| cross-section | 6.4 m high, 4.9 m wide | |

| construction | ||

| Client | Northern Pacific Railway | |

| building-costs | US $ 1,013,006.63 | |

| start of building | 1886 | |

| completion | 1888 | |

| business | ||

| operator | BNSF , (originally Northern Pacific Railway ) | |

| release | 1888 | |

| closure | still active | |

| location | ||

|

|

||

| Coordinates | ||

| East portal | 47 ° 16 ′ 42 " N , 121 ° 19 ′ 27" W. | |

| West portal | 47 ° 16 ′ 0 ″ N , 121 ° 21 ′ 36 ″ W. | |

The first tunnel was planned by James T. Kingsbury, assistant engineer, in August 1882. Further tunnels were planned by the engineers named below, but had practically the same starting point at the west end: John A. Hulburt, John Quincy Barlow and FC Tucker. The final decision was made by William H. Kennedy.

JQ Jamieson was the assistant engineer in charge from the start of the work until October 23, 1887, when he was replaced by Edwin Harrison McHenry (later chief engineer of the Northern Pacific ), who was responsible for the completion of the tunnels, snow barriers and sidings held both tunnel exits.

FM Haines was responsible for the passage at the west end and Andrew Gibson was responsible for the passage at the east end; both worked for the entire construction period. NB Tunder was the superintendent of the contractor on the west end; the same position was held by Captain Sidney J. Bennet, a brother of the contractor, at the Ostend.

The contract to drive the tunnel was awarded on January 21, 1886 to Nelson Bennett. Work on the Ostend began with hand drilling on February 13, 1886. Air pressure drills were introduced on June 18, 1886. The hand drills achieved an average daily advance of 1.07 meters, the air pressure drill 1.77 meters. At the west end, work with hand drills began on April 1, 1886. Air pressure drills were introduced on September 1, 1886. The average advance with hand drills was 1.22 m, with air pressure drills 2.1 m. The drill heads met on May 3, 1888, and the tunnel breakthrough took place on May 11, 1888. The tunnel was opened to traffic on May 27, 1888. The tunneling cost was US $ 767,839.80, which at 3,000.48 meters was equivalent to US $ 78 per foot (US $ 255.90 per meter). There were still US $ 138,864.50 for the extra excavation of 880.11 m³ (31,081 cubic feet), thus US $ 157.78 per m³ (US $ 4.50 per cubic foot), and US $ 105,302.33 for the Alignment. The total cost was US $ 1,013,006.63. The victims were 17 dead and 17 injured on the west side and 11 dead and 22 injured on the east side. One was killed by a construction train. The lining of the tunnel began on June 16, 1889 and was completed on November 16, 1895. This cost US $ 54.08 per foot. A foreman was killed by a falling rock, two workers were killed by a construction train, and another worker was electrocuted. 7,310.1 m³ of cement were used. Most of the 9,816,620 bricks were from Tacoma.

The railway tunnel at Stampede Pass is arched in the middle so that no daylight can be seen from one end of the tunnel at the other; In contrast, the first two Cascade Tunnels of the Great Northern Railway at Stevens Pass (2.6 miles - 4.2 km - or 7.8 miles - 15.6 km - long and built in 1900 and 1929) are in a straight line and built at a constantly sloping angle from northeast to southwest. Since steam locomotives have to cope with an increase in every direction within the Stampede Tunnel, passengers and accompanying personnel were almost fatally shocked by the gases remaining in the tunnel; as a result, forced ventilation was later installed on the west side. The increase is 2.2% on the east side and 2.2% on the west side from Lester. A single track in standard gauge runs through the tunnel .

Andrew Gibson, born and educated in Scotland , began working for the NP in Main Line Construction in Oregon , about eight miles west of Portland . He was initially secretary to Mr. O. Phil, assistant engineer, from July 1, 1883, and remained in that position until the department was dissolved around the end of October. In January 1884 he was a leveler for Colin Mcintosh, assistant engineer on the Kalama Slope. He also worked from April 27, 1884 as a "bush hook dude" with William H. Kennedy in the Cascade Division Surveys , which started in South Prairie and worked their way east. He was promoted to a surveyor's assistant in early June and a leveler in mid-August when the 25-mile (40 km) stretch between South Prairie and Eagle Gorge was completed. Gibson helped engineers William T. Chalk, John Quincy Barlow, JQ Jamieson, and Herbert S. Huson, literally everyone on the Stampede Pass line. Gibson continued ascending, working the topography at the hairpin and working on the tunnel line that crossed the Yakima River in Yakima Canyon . Eventually he became an assistant engineer himself, overseeing the tunnel alignment and filling in the numerous temporary trestles that were being built in a hurry to meet the completion date. It is primarily thanks to his conscientious work that detailed first-hand reports of the work are available. Gibson continued overseeing the construction of the NP in the Palouse and the giant belt factory in Paradise, Montana . He eventually became the chief engineer in charge of maintaining the streets of Saint Paul . He humbly began clearing what would later become the main street of the northwest.

Two-track expansion

A major overhaul of the line from Lester to the Stampede Tunnel was carried out between 1912 and 1915. A new engine shed in Lester, double tracks from Lester to the west entrance of tunnel 4 and a small tunnel just one mile (1.6 km) west of the Stampede Tunnel were built, and the previous loop over Weston was replaced by a large steel viaduct. At the same time, the line from Martin , located on the east portal, to Easton was expanded to double tracks.

In August 1984, the Burlington Northern closed the line as redundant. Between 1995 and 1996, the BN and its successor, the BNSF Railway, reopened the line in response to increasing traffic in the Pacific Northwest. Since 2007, the BNSF and Washington government agencies have committed to expanding the Stampede Tunnel to allow larger intermodal freight cars to pass; the current height of 6.7 meters is unsuitable for double-decker intermodal wagons.

tourism

The Northern Pacific opened a ski area on the east portal of the Stampede Tunnel in 1939, called the Martin Ski Dome . The resort was to rival the Milwaukee Ski Bowl on Milwaukee Road in Hyak , a few miles north , which opened in 1937. The Martin Ski Dome was closed in 1942 with the start of World War II and sold to the University of Washington Students Association in 1946 after the war ended . It was reopened as the "Husky Chalet" with two tow lifts . Operations continued until 1956 when heavy snowfalls brought the property to collapse. This ski area was never rebuilt.

The Mountaineers in the Pacific Northwest also operate a ski area southeast of the east portal of the Stampede Tunnel. The Meany Lodge with three tow lifts was built in 1928 and is open to everyone on winter weekends from early January to early March. It has a PSIA-certified winter sports school and is one of the oldest ski areas in the country.

The only public access to the pass is in the east; access from the west is not public because this area is part of the Green River area, which is managed by the Tacoma Public Utilities ( Tacoma Water ) and is partly owned by them; the lock is used to secure clean and fresh water for Tacoma's water supply.

See also

- Easton (Washington)

- Lester (Washington)

- Roslyn (Washington)

- Cascade Tunnel - Great Northern

- Snoqualmie Tunnel - Milwaukee Road

Web links

- Weather report from NOAA for the pass

- Meany Lodge - official website

- Stampede Pass in the United States Geological Survey's Geographic Names Information System

Individual evidence

- ↑ tunnel . In: The New International Encyclopedia , Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1904, p. 998.

- ↑ a b Heather M. MacIntosh: Stampede Pass tunnel opens on May 27, 1888 . In: HistoryLink.org , February 22, 1999. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ a b David Wilma: Burlington Northern Sante Fe Railroad reopens Stampede Pass line on December 5, 1996 . In: HistoryLink.org , July 29, 2005. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ to stampede

- ^ WP Bonney, Secretary (Washington) State Historical Society, to 29th Annual Farmers Picnic, Enumclaw, 8-6-21. Bonney worked on the Stampede Pass in 1881/82.

- ↑ Virgil G. Bogue: Stampede Pass, Cascade Range (Washington) . In: Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York, Vol. 27, No. 3 (1895), pp. 239-255 at p. 254 . American Geographical Society of New York. 1895. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- ^ Sprau, DT (2002, January). How Auburn became a railroading town Part i: Featuring the Northern Pacific's "Palmer Cutoff" . Retrieved from http://www.wrvmuseum.org/journal/journal_0102.htm

- ↑ Stampede Tunnel . In: Bridgehunter.com . Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ John W. Lundin: Skiing at Martin, the Northern Pacific Stop at Stampede Pass . In: HistoryLink.org , September 12, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Green River Watershed