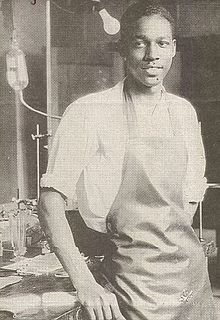

Vivien Thomas

Vivien Theodore Thomas (* 29. August 1910 in New Iberia , Louisiana ; † 26. November 1985 ) was an American surgeon's assistant and semi-skilled surgeon , the much in the 1940s to develop a method of treatment of blue baby syndrome involved was. He was an assistant to Alfred Blalock at Vanderbilt University in Nashville , Tennessee, and later at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore , Maryland . Although Thomas did not have any secondary school education, he was one of the pioneers in cardiac surgery .

Childhood and youth

Vivien Thomas was born in New Iberia, a town near Lake Providence , Louisiana. He attended Pearl High School in Nashville in the 1920s. Despite the racial segregation that was prevalent in the American educational system at the time , the African American received a comparatively good schooling. He was unable to realize his plans to attend college and study medicine after high school due to his economic situation during the Great Depression . He worked as a carpenter and caretaker and got to know the surgeon Alfred Blalock in this context.

Collaboration with Alfred Blalock

From the beginning, Thomas showed an extraordinary interest and aptitude for surgery, whereupon Blalock increasingly involved him in his work. Blalock taught him, together with his research associate Joseph Beard, the anatomical and physiological fundamentals that allowed Thomas to master difficult surgical techniques and research methods. Despite the great respect shown to each other and their excellent cooperation, their social contact remained distant due to their different skin colors. In the 1930s, marked by segregation and racism , Thomas was referred to and paid as a caretaker , although he was a post-graduate student in Blalock's laboratory .

Together, they achieved pioneering research into the causes of hemorrhagic and traumatic shock. This work later moved on to research into crush syndrome and was crucial in the treatment of wounded soldiers during World War II . It was during this phase that Thomas and Blalock began experimenting in cardiac and vascular surgical techniques, although medicine at the time still rejected open-heart surgery. This research became the basis of the revolutionary and life-saving surgical techniques that they carried out a decade later at Johns Hopkins University .

Johns Hopkins

In 1941, due to his success, Blalock was offered the position of chief of surgery at Johns Hopkins University and he suggested that Thomas accompany him. Thomas arrived in Baltimore that same year with his wife Clara and their young child. In addition to a very difficult situation on the housing market, Thomas encountered a far more pronounced segregation there than in the south. At Johns-Hopkins, for example, African Americans were only employed as caretakers, so Thomas caused a sensation with his white doctor's coat.

Blue baby syndrome

In 1943, while continuing his research into traumatic shock, Blalock was approached by the well-known pediatric surgeon Helen Taussig , who was looking for a treatment for the complex and fatal Fallot tetralogy known as blue baby syndrome . In this malformation, the newborn's blood bypasses the lungs, which results in an insufficient supply of oxygen, which manifests itself as a cyanotic blue color . According to Thomas' autobiographical notes, Taussig suggested "reconnecting the pipes" to bring more blood to the lungs, but had no idea what a surgical solution might look like. It was clear to Blalock and Thomas that the answer might lie in a technique they had developed for a completely different problem while working on the Vanderbilt.

Thomas was initially commissioned to a dog a corresponding syndrome cyanosis cause and this state by creating a connection between the lung and subclavian artery pick up again. Among the 200 dogs that Thomas operated on within two years to perfect the method was Anna, a laboratory dog and long-term survivor of the experiment, who is the only animal shown in a portrait on the premises of Johns Hopkins University. After two years, Thomas was able to treat two of the four anomalies of the Fallot tetralogy, which can be reconstructed in dogs, demonstrably without fatal consequences, and he convinced Blalock that the surgical method could be transferred to humans without serious consequences for the operated person.

On November 29, 1944, the new method was first performed on a human, Eileen Saxton. The cyanosis had stained her lips and fingers blue, and her face was also slightly bluish. She could only take a few steps before she became short of breath. During the operation, Thomas stood behind Blalock and gave him advice on how to carry out the procedure, as he had performed the procedure on dogs much more often than Blalock. Although the operation was not as successful as hoped, it added two months to the patient's life. Blalock and his team then operated on an eleven-year-old girl, this time with resounding success: the patient was able to leave the hospital three weeks later. The next operation was a six-year-old boy whose complexion changed almost dramatically from blue to pink at the end of the operation. These three cases formed the basis for the May 1945 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association that named Blalock and Taussig as the authors of the new method. Thomas was not mentioned.

Failure to acknowledge Thomas' contribution to success

Immediately after the article appeared, the news went around the world, newsreels also reported on it, which significantly increased the reputation of the Johns Hopkins Institute. Blalock, whose career had recently hung by a thread, also benefited from the success. The new method came to be known as the Blalock-Taussig shunt , but Vivien Thomas's involvement was not mentioned by Blalock or Johns Hopkins University. More than 200 such operations have been carried out within a year.

Thomas began to train others in the surgical method and thus became a legend for the young surgeons, the epitome of an extremely precise and efficient surgeon. He owed surgeons such as Denton Cooley , Alex Haller, Frank Spencer, Rowena Spencer, and others, the transmission of surgical techniques that raised them into the first medical guard in the United States. Despite the deep respect he was shown by these surgeons and many of his African American laboratory technicians whom he taught at Johns Hopkins, Thomas was still poorly paid. He even worked as a bartender at times, especially at parties that Blalock hosted. This led to situations where he served drinks to people he had previously taught the same day. After negotiating with Blalock, Thomas was finally the highest paid technician and African American at Johns Hopkins University in 1946. The hospital records show that Blalock received ten times the salary from 1943 to 1947.

Although Thomas never spoke publicly about his plans, his widow Clara Flanders revealed Thomas in an interview with the Washingtonian in 1987 that Thomas tried again to go to college in 1947 to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He signed up at Morgan State University , but his previous achievements did not want to be credited to him. He found that if he went through all of the training, he would be 50 years old before he could even practice. So he gave up on this idea.

Relationship with Blalock

The relationship between Blalock and Thomas turned out to be complicated because of racial segregation. On the one hand, Blalock defended Thomas and broke through - actually unthinkable at the time - some racial barriers in order to be able to keep him as a technician. On the other hand, there were limits to his tolerance, especially when it came to money, academic education, and social contacts outside of work.

After Blalock died of cancer in 1964 at the age of 65, Thomas stayed at Johns-Hopkins for 15 years.

Late recognition

In 1976 Thomas was awarded an honorary doctorate from Johns Hopkins University . However, due to restrictions in force, he received an honorary doctorate in law and not in medicine. However, Thomas received a higher income after he was accepted into the faculty of Johns Hopkins University without a degree.

Thomas wrote an autobiography , "Partners of the Heart". He died at the age of 75 and his book appeared just days later. The case became known in 1989 through an article by journalist Katie McCabe in Washingtonian magazine ( Like something the Lord made ).

His life story was filmed in 2004 under the title Ein Werk Gottes (Like something the Lord made) by HBO and in 2003 there was a TV film about the partnership between the two surgeons (Partners of the Heart).

literature

- Vivien Thomas: Partners of the Heart: Vivien Thomas and His Work with Alfred Blalock: An Autobiography , University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8122-1634-2

- Katie McCabe: Like Something the Lord Made In: Washingtonian Magazine, August 1989

- American Experience: Partners of the Heart, 2003

- Stefan Timmermans: A Black Technician and Blue Babies in Social Studies of Science 33: 2, April 2003, pages 197-229

Individual evidence

- ↑ Blalock, Taussig The surgical treatment of malformations of the heart in which there is a pulmonary stenosis or pulmonary atreria , Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 128, 1945, p. 189

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Thomas, Vivien |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Thomas, Vivien Theodore (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | African-American surgical assistant and trained surgeon |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 29, 1910 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New Iberia |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 26, 1985 |