Legio volonum

As legio volonum (German "Legion of volunteers", plural legiones volonum ), a legion of volunteers is referred to in Roman antiquity . The Roman Senate set up two associations of this type in 216 BC. Set up during the Second Punic War . Most of their teams were recruited from slaves that the state had purposefully purchased for military use. Apart from a number of slaves, which may have been distributed to existing legions under Emperor Marcus Aurelius , this was the only documented case of unfree serving as regular soldiers (milites) in the Roman army.

Unfree volones in the Roman Republic

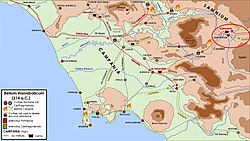

After the lost battle of Cannae , Rome had to take extraordinary measures to compensate for eight lost legions. Under the consul Gaius Terentius Varro , the remaining soldiers were reorganized into two new legions and new recruits were quickly recruited, including suitable unfree people. Of the slaves, 8,000 fit men accepted the military service offered by the state willingly as volunteers (volones) in order to be divided into two closed combat units.

The slave status of the volunteers remained after entering service as a regular combatant . Only after the legiones volonum came under the command of Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus in 214 BC. BC in the First Battle of Beneventum had triumphed over the Carthaginian troops under Hanno , the surviving volones were rewarded with their solemn release ( libertas ) , with the granting of civil rights ( civitas ) .

After Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus in 212 BC. B.C. had died in an ambush, the legiones volonum apparently dissolved. The formerly unfree saw themselves only obliged to the general and with his death as released from service. The rest of the army was led past Capua to Rome under the leadership of Quaestor Cornelius .

Not until 207 BC The volones were called to arms again, as far as they could still be reached by the state, and distributed among two existing legions.

Unfree volones in the Roman Empire

A comparable type of recruiting of unfree persons and even those who were outside the law is handed down in the - albeit often unreliable - Historia Augusta in the Roman imperial period under Marcus Aurelius around 170 AD . The incursion of Germanic tribes into the Danube provinces and northern Italy, which had been preceded by a military operation that cost Rome a lot , and the Antonine plague, with its enormous number of soldiers killed, are said to have made recruitment necessary, following the example from the campaign against Hannibal . Presumably, however, no separate troop bodies were formed, but only the failed personnel of the legions were replaced by the volunteers. In this case, too, the unfree soldiers are said to have been given the prospect of freedom and Roman citizenship for bravery.

Slave recruitment as a historical exception

The two traditional recruitments of slaves into the Roman army were exceptions to the current Roman recruitment practice and forced by extreme circumstances. In principle, unfree people were not allowed to be armed or used as combatants in the army for security reasons.

During the Pannonian crisis and after the loss of three legions and auxiliary troops in the Varus Battle , Augustus also had an unknown number of slaves raised for military service in order to use them primarily as reserve and border security troops. However, these had to have been emancipated from their owners before entering service .

Even with the defeat of the Bar Kochba uprising in the years 133 and 134, which was costly for Rome, recourse was not made to unfree but to already emancipated naval crews from Misenum . The soldiers were also given civil rights before they were incorporated into the legions.

Legal considerations

Apart from the similar but less strict requirements that were placed on the members of the auxiliary troops, the applicant's existing military worth was a mandatory prerequisite for being able to take up military service as a recruit in a legion. These included, in particular, freedom and the possession of Roman citizenship. An intentional concealment of the unfree civil status and the pretense of civil rights were considered a capital offense when exposed. This forfeited offense usually resulted in a severe sanction, up to and including the execution of the deceiver, as a legal consequence.

The extraordinary case of a runaway slave (fugitivus) has been handed down under Domitian . The fugitive unfree managed to conceal his true identity in order to then join the army as a recruit. There he proved himself and rose to the rank of centurion . After the officer's true civil status became known, he was removed from the army at the behest of the emperor and given to his owner. A more severe punishment had been refrained from, presumably because of the service rendered and the promotions that went with it.

The ban on the recruitment of unfree people was interpreted in the 3rd century in such a way that the Roman lawyer Ulpian also classified as unworthy of defense those people who, when they were recruited, mistakenly assumed that they still belonged to the slave class, but were in fact already free.

reception

Legio volonum

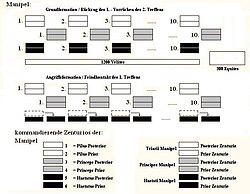

In modern research, it is considered likely that the excavated volones were initially only used to defend the city of Rome and were integrated into the still existing regular protection forces as reinforcement. The Roman leadership, which was still under the impression of the catastrophic defeat at Cannae, feared an attack by Hannibal, so that quick, unconventional measures were perfectly suitable and necessary. After the feared siege failed to materialize, the unfree were first trained militarily in order to then be divided into existing combat units of the Italian allies. The designation of the units as legio volonum , in which the unfree served, would only have been owed to the fact that the number of 8,000 men they have handed down was due to the fact that the halving would have been appropriate for the emergence of the two-legion version. Furthermore, it is argued that the battle line-up to be adopted by a legion in meeting tactics ( hastati , principes and triarii ), which would only have consisted of freshly trained recruits, could never have been suitable for combat against a combat-tested troop.

The unilateral acknowledgment of service by the now emancipated volones, as described by the Roman historian Livy, and their subsequent reassignment are also questioned in today's research. Accordingly, it seems questionable here to what extent deserters, who should be seen as such the defunct soldiers, on the one hand go out with impunity and on the other hand could be accepted back into the army. The described reactivation of the volones therefore apparently referred to soldiers who had previously been properly dismissed from service and who did not desert after the death of Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus.

Unfree volones under Marcus Aurelius

The credibility of the recruiting of unfree people, handed down in the Historia Augusta, who entered the service as slaves in the legions, is controversial in recent research. In addition to the tradition from the aforementioned work, there are no other sources that could confirm the recruitment and use of unfree people, especially gladiators in the army of Marcus Aurelius.

The aforementioned recruitment of robber gangs (latrones) is assumed to be dubious , because on the one hand it would have been possible to get hold of them only with considerable effort and on the other hand a multiple number of personnel would have been necessary for supervision. It is believed that the contingent in question may have been mountain tribes who were generally considered to be predatory. Thus, according to Karl-Wilhelm Welwei and other ancient historians, the measures that the emperor must take to reinforce troops are unclear or incorrectly documented.

Alexander Demandt , on the other hand, assumes that due to the plight and the severe lack of voluntary recruits access to unfree and preferably trained gladiators was a necessary consequence. With regard to the Illyrian robbers, he assumes that they have reported themselves for military service.

The term voluntarii used in the Historia Augusta was part of the regular military jargon and was not applicable to slaves or volones according to the unique example of the republic. The Roman provincial archaeologist Alfred Neumann therefore noted that the biographer of Markusvita, precisely because he used the term voluntarii , could accept the voluntary recruitment of slaves as certain.

Remarks

- ↑ Alfred Klotz : The designation of the Roman legions. In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie , Volume 81, 1932, pp. 143–154 (PDF; 2.5 MB)

- ↑ Titus Livius , Ab urbe condita 22,57,11 (German translation)

- ↑ Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius , Saturnalia 1,11,30 ( online )

- ↑ Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita 24,11,3 (German translation)

- ↑ Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita 24.14.1-24.16.9 (German translation)

- ↑ Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita 25,20,4 (German translation)

- ↑ Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita 25,19,4 (German translation)

- ↑ Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita 28,10,11 (German translation)

- ↑ Historia Augusta , Marcus Aurelius 21.6 (English translation)

- ↑ Suetonius , Augustus , 25.2 (English translation)

- ↑ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei : Unfree in ancient military service . Steiner et al. a., Wiesbaden a. a. 1974–1988 (also: Bochum, University, habilitation thesis, 1970/1971); Volume 3: Rome (= research on ancient slavery. Vol. 21). 1988, ISBN 3-515-05206-2 , slavery under Augustus. Pp. 18-22.

- ^ Christian Mann : Military and warfare in antiquity (= encyclopedia of Greco-Roman antiquity. Volume 9). Oldenbourg, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-59682-3 , pp. 114-115.

- ↑ Pliny the Younger , Epistulae 10.30 (German translation) .

- ↑ Cassius Dio , Römische Geschichte 67,13,1 (English translation) .

- ↑ Heinz Bellen : Studies on the escape of slaves in the Roman Empire . Wiesbaden 1971, p. 30f.

- ↑ Ulpian , Digest 49,16,8 (online)

- ↑ Alexander Demandt : Marc Aurel. The emperor and his world. Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-406-71874-8 , The First German War, m. Recruitment of gladiators and Germanic tribes, pp. 201, 202.

- ↑ Alfred Neumann : Volones. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IX A, 1, Stuttgart 1961, Col. 772.

literature

- Alfred Klotz : The Roman Wehrmacht in the 2nd Punic War. In: Philologus. Journal for ancient literature and its reception , Volume LXXXVIII, I (= New Series, Volume XLII, I), 1933, pp. 42–89 ( online ).

- Alfred Neumann : Volones. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IX A, 1, Stuttgart 1961, Col. 772.

- Alfred Neumann : Volones. In: The Little Pauly (KlP). Volume 5, Stuttgart 1975, column 1322 f.

- Leonhard Schumacher : Volones. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/2, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01487-8 , Sp. 311 ( excerpt online ).

- Karl-Wilhelm Welwei : Unfree in ancient military service . Steiner et al. a., Wiesbaden a. a. 1974–1988 (also: Bochum, University, habilitation thesis, 1970/1971); Volume 3: Rome (= research on ancient slavery. Vol. 21). 1988, ISBN 3-515-05206-2 , The so-called volones , pp. 5-18, Slaves in Mark Aurel's army? , Pp. 22-27.